Chapter 3: Fungal Skin Infections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Article Fungal Dimorphism and Virulence: Molecular Mechanisms for Temperature Adaptation, Immune Evasion, and in Vivo Survival

Hindawi Mediators of Inflammation Volume 2017, Article ID 8491383, 8 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8491383 Review Article Fungal Dimorphism and Virulence: Molecular Mechanisms for Temperature Adaptation, Immune Evasion, and In Vivo Survival Gregory M. Gauthier Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Gregory M. Gauthier; [email protected] Received 18 November 2016; Accepted 12 April 2017; Published 23 May 2017 Academic Editor: Anamélia L. Bocca Copyright © 2017 Gregory M. Gauthier. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The thermally dimorphic fungi are a unique group of fungi within the Ascomycota phylum that respond to shifts in temperature by ° ° converting between hyphae (22–25 C) and yeast (37 C). This morphologic switch, known as the phase transition, defines the biology and lifestyle of these fungi. The conversion to yeast within healthy and immunocompromised mammalian hosts is essential for virulence. In the yeast phase, the thermally dimorphic fungi upregulate genes involved with subverting host immune defenses. This review highlights the molecular mechanisms governing the phase transition and recent advances in how the phase transition promotes infection. 1. Introduction are more typically phytopathogenic or entomopathogenic. For example, Ophiostoma novo-ulmi, the etiologic agent The ability for fungi to switch between different morphologic of Dutch elm disease, has destroyed millions of elm trees forms is widespread throughout the fungal kingdom and is a in Europe and United States [13]. -

Series Fungal Infections 8 Improvement of Fungal Disease

Series Fungal infections 8 Improvement of fungal disease identification and management: combined health systems and public health approaches Donald C Cole, Nelesh P Govender, Arunaloke Chakrabarti, Jahit Sacarlal, David W Denning More than 1·6 million people are estimated to die of fungal diseases each year, and about a billion people have Lancet Infect Dis 2017 cutaneous fungal infections. Fungal disease diagnosis requires a high level of clinical suspicion and specialised Published Online laboratory testing, in addition to culture, histopathology, and imaging expertise. Physicians with varied specialist July 31, 2017 training might see patients with fungal disease, yet it might remain unrecognised. Antifungal treatment is more http://dx.doi.org/10.1016 S1473-3099(17)30308-0 complex than treatment for bacterial or most viral infections, and drug interactions are particularly problematic. See Online/Series Health systems linking diagnostic facilities with therapeutic expertise are typically fragmented, with major elements http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ missing in thousands of secondary care and hospital settings globally. In this paper, the last in a Series of eight papers, S1473-3099(17)30303-1, we describe these limitations and share responses involving a combined health systems and public health framework http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ illustrated through country examples from Mozambique, Kenya, India, and South Africa. We suggest a mainstreaming S1473-3099(17)30304-3, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ approach including greater integration of fungal diseases into existing HIV infection, tuberculosis infection, diabetes, S1473-3099(17)30309-2, chronic respiratory disease, and blindness health programmes; provision of enhanced laboratory capacity to detect http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ fungal diseases with associated surveillance systems; procurement and distribution of low-cost, high-quality antifungal S1473-3099(17)30306-7, medicines; and concomitant integration of fungal disease into training of the health workforce. -

Severe Chromoblastomycosis-Like Cutaneous Infection Caused by Chrysosporium Keratinophilum

fmicb-08-00083 January 25, 2017 Time: 11:0 # 1 CASE REPORT published: 25 January 2017 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00083 Severe Chromoblastomycosis-Like Cutaneous Infection Caused by Chrysosporium keratinophilum Juhaer Mijiti1†, Bo Pan2,3†, Sybren de Hoog4, Yoshikazu Horie5, Tetsuhiro Matsuzawa6, Yilixiati Yilifan1, Yong Liu1, Parida Abliz7, Weihua Pan2,3, Danqi Deng8, Yun Guo8, Peiliang Zhang8, Wanqing Liao2,3* and Shuwen Deng2,3,7* 1 Department of Dermatology, People’s Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Urumqi, China, 2 Department of Dermatology, Shanghai Changzheng Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China, 3 Key Laboratory of Molecular Medical Mycology, Shanghai Changzheng Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China, 4 CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Utrecht, Netherlands, 5 Medical Mycology Research Center, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan, 6 Department of Nutrition Science, University of Nagasaki, Nagasaki, Japan, 7 Department of Dermatology, First Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, China, 8 Department of Dermatology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China Chrysosporium species are saprophytic filamentous fungi commonly found in the Edited by: soil, dung, and animal fur. Subcutaneous infection caused by this organism is Leonard Peruski, rare in humans. We report a case of subcutaneous fungal infection caused by US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA Chrysosporium keratinophilum in a 38-year-old woman. The patient presented with Reviewed by: severe chromoblastomycosis-like lesions on the left side of the jaw and neck for 6 years. Nasib Singh, She also got tinea corporis on her trunk since she was 10 years old. -

HIV-Associated Disseminated Emmonsiosis, Johannesburg, South Africa

LETTERS and vesical veins, as well as in the 2. Berry A, Moné H, Iriart X, Mouahid order mammals (1). Although emmon- liver and the portal system. G, Abbo O, Boissier J, et al. Schistoso- sia rarely infect humans, the fungi can miasis haematobium, Corsica, France In a more comprehensive study [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1595–7. cause localized granulomatous pul- (9), Bulinus snails were found in all http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2009.140928. monary disease (adiaspiromycosis) in of Corsica’s coastal rivers, except for 3. Brumpt E. Cycle évolutif du Schistosoma immunocompetent persons (1–4). Be- those in the northwestern-most part of bovis (Bilharzia crassa); infection spon- fore 2013, no association was known tanée de Bulinus contortus en Corse C.-R. the island. However, of the 55 bod- Acad. Sci. 1929;CLXXXXI:879. between emmonsia and HIV, and there ies of water where Bulinus snails were 4. Brumpt E. Cycle évolutif complet de was no indication that emmonsia were found, only 1 contained gastropods Schistosoma bovis. Infection naturelle en endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. with Schistosoma cercariae, and re- Corse et infection expérimentale de Buli- In 2013 a novel Emmonsia sp. nus contortus. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. sults of a search for blood flukes in 220 1930;VIII:17–50. that is closely related to E. pasteuriana small rodents (known for being sus- 5. Pandey VS, Ziam H. Helminthoses cir- was described. The fungus caused dis- ceptible to S. bovis and captured near culatoires. In: Lefèvre P-C, Blancou J, seminated disease in 13 HIV-infected bodies of water where Bulinus snails Charmette R, editors. -

Detection of Histoplasma DNA from Tissue Blocks by a Specific

Journal of Fungi Article Detection of Histoplasma DNA from Tissue Blocks by a Specific and a Broad-Range Real-Time PCR: Tools to Elucidate the Epidemiology of Histoplasmosis Dunja Wilmes 1,*, Ilka McCormick-Smith 1, Charlotte Lempp 2 , Ursula Mayer 2 , Arik Bernard Schulze 3 , Dirk Theegarten 4, Sylvia Hartmann 5 and Volker Rickerts 1 1 Reference Laboratory for Cryptococcosis and Uncommon Invasive Fungal Infections, Division for Mycotic and Parasitic Agents and Mycobacteria, Robert Koch Institute, 13353 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] (I.M.-S.); [email protected] (V.R.) 2 Vet Med Labor GmbH, Division of IDEXX Laboratories, 71636 Ludwigsburg, Germany; [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (U.M.) 3 Department of Medicine A, Hematology, Oncology and Pulmonary Medicine, University Hospital Muenster, 48149 Muenster, Germany; [email protected] 4 Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Essen, University Duisburg-Essen, 45147 Essen, Germany; [email protected] 5 Senckenberg Institute for Pathology, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt, 60323 Frankfurt am Main, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-30-187-542-862 Received: 10 November 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: Lack of sensitive diagnostic tests impairs the understanding of the epidemiology of histoplasmosis, a disease whose burden is estimated to be largely underrated. Broad-range PCRs have been applied to identify fungal agents from pathology blocks, but sensitivity is variable. In this study, we compared the results of a specific Histoplasma qPCR (H. qPCR) with the results of a broad-range qPCR (28S qPCR) on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens from patients with proven fungal infections (n = 67), histologically suggestive of histoplasmosis (n = 36) and other mycoses (n = 31). -

New Histoplasma Diagnostic Assays Designed Via Whole Genome Comparisons

Journal of Fungi Article New Histoplasma Diagnostic Assays Designed via Whole Genome Comparisons Juan E. Gallo 1,2,3, Isaura Torres 1,3 , Oscar M. Gómez 1,3 , Lavanya Rishishwar 4,5,6, Fredrik Vannberg 4, I. King Jordan 4,5,6 , Juan G. McEwen 1,7 and Oliver K. Clay 1,8,* 1 Cellular and Molecular Biology Unit, Corporación para Investigaciones Biológicas (CIB), Medellín 05534, Colombia; [email protected] (J.E.G.); [email protected] (I.T.); [email protected] (O.M.G.); [email protected] (J.G.M.) 2 Doctoral Program in Biomedical Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá 111221, Colombia 3 GenomaCES, Universidad CES, Medellin 050021, Colombia 4 School of Biological Sciences, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA; [email protected] (L.R.); [email protected] (F.V.); [email protected] (I.K.J.) 5 Applied Bioinformatics Laboratory, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA 6 PanAmerican Bioinformatics Institute, Cali, Valle del Cauca 760043, Colombia 7 School of Medicine, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín 050010, Colombia 8 Translational Microbiology and Emerging Diseases (MICROS), School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá 111221, Colombia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Histoplasmosis is a systemic fungal disease caused by the pathogen Histoplasma spp. that results in significant morbidity and mortality in persons with HIV/AIDS and can also affect immuno- competent individuals. Although some PCR and antigen-detection assays have been developed, Citation: Gallo, J.E.; Torres, I.; conventional diagnosis has largely relied on culture, which can take weeks. Our aim was to provide Gómez, O.M.; Rishishwar, L.; a proof of principle for rationally designing and standardizing PCR assays based on Histoplasma- Vannberg, F.; Jordan, I.K.; McEwen, specific genomic sequences. -

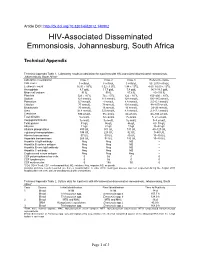

Technical Appendix

Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2012.140902 HIV-Associated Disseminated Emmonsiosis, Johannesburg, South Africa Technical Appendix Technical Appendix Table 1. Laboratory results at admission for 3 patients with HIV-associated disseminated emmonsiosis, Johannesburg, South Africa* Laboratory investigation Case 1 Case 2 Case 3 Reference range CD4 count 5 cells/µL 3 cells/µL 0 cells/µL 50–2010 cells/µL Leukocyte count 16.91 × 109/L 1.52 ×1 09/L 1.84 × 109/L 4.00–10.00 × 109/L Hemoglobin 8.7 g/dL 11.7 g/dL 7.8 g/dL 14.3–18.3 g/dL Mean cell volume 91 fL 90 fL 87.6 fL 83–101 fL Platelets 523 × 109/L 74 × 109/L 122 × 109/L 150–400 × 109/L Sodium 121 mmol/L 111 mmol/L 128 mmol/L 136–145 mmol/L Potassium 3.7 mmol/L 4 mmol/L 4.8 mmol/L 3.5–5.1 mmol/L Chloride 77 mmol/L 79 mmol/L 101 mmol/L 98–107mmol/L Bicarbonate 30 mmol/L 16 mmol/L 16 mmol/L 23–29 mmol/L Urea 31.4 mmol/L 5.5 mmol/L 4.8 mmol/L 2.1–7.1 mmol/L Creatinine 590 µmol/L 55 µmol/L 64 µmol/L 64–104 µmol/L Total bilirubin 5 µmol/L 12 µmol/L 7 µmol/L 5–21 µmol/L Conjugated bilirubin 3 µmol/L 9 µmol/L 5 µmol/L 0–3 µmol/L Total protein 51 g/L 56 g/L 46 g/L 60–78 g/L Albumin 11 g/L 22 g/L 13 g/L 35–52 g/L Alkaline phosphatase 400 U/L 301 U/L 131 U/L 40–120 U/L γ-glutamyl transpeptidase 396 U/L 228 U/L 92 U/L 0–60 U/L Alanine transaminase 37 U/L 53 U/L 40 U/L 10–40 U/L Aspartate transaminase 266 U/L 94 U/L 145 U/L 15–40 U/L Hepatitis A IgM antibody Neg Neg ND – Hepatitis B surface antigen Neg Neg ND – Hepatitis B core IgM antibody Neg Neg ND – Hepatitis C antibody Neg Neg ND – Cryptococcal serum antigen Neg Neg Neg – CSF polymorphonuclear cells 0 0† 0 0 CSF lymphocytes 0 0† 0 0 CSF erythrocytes 0 18† 30 0 *CD4, CD4+ T-cell; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ND, not done; Neg, negative; NG, no growth. -

Neglected Fungal Zoonoses: Hidden Threats to Man and Animals

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector REVIEW Neglected fungal zoonoses: hidden threats to man and animals S. Seyedmousavi1,2,3, J. Guillot4, A. Tolooe5, P. E. Verweij2 and G. S. de Hoog6,7,8,9,10 1) Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, 2) Department of Medical Microbiology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 3) Invasive Fungi Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran, 4) Department of Parasitology- Mycology, Dynamyic Research Group, EnvA, UPEC, UPE, École Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort, Maisons-Alfort, France, 5) Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran, 6) CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, 7) Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8) Peking University Health Science Center, Research Center for Medical Mycology, Beijing, 9) Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China and 10) King Abdullaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Abstract Zoonotic fungi can be naturally transmitted between animals and humans, and in some cases cause significant public health problems. A number of mycoses associated with zoonotic transmission are among the group of the most common fungal diseases, worldwide. It is, however, notable that some fungal diseases with zoonotic potential have lacked adequate attention in international public health efforts, leading to insufficient attention on their preventive strategies. This review aims to highlight some mycoses whose zoonotic potential received less attention, including infections caused by Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei, Lacazia loboi, Emmonsia spp., Basidiobolus ranarum, Conidiobolus spp. -

Approach to Fungal Infections in HIV-Infected Individuals: Pneumocystis and Beyond

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author Manuscript Author ManuscriptClin Chest Author Manuscript Med. Author Author Manuscript manuscript. Approach to fungal infections in HIV-infected individuals: Pneumocystis and beyond Richard J. Wang, MD1, Robert F. Miller, MBBS, CBiol, FRSB, FRCP2, and Laurence Huang, MD1 Richard J. Wang: [email protected]; Robert F. Miller: [email protected]; Laurence Huang: [email protected] 1University of California San Francisco, USA 2Research Department of Infection and Population Health, Institute of Epidemiology and Healthcare University College London, London, UK, and Department of Clinical Research, Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK SYNOPSIS Many fungi cause pulmonary disease in HIV-infected patients. Major pathogens include Pneumocystis jirovecii, Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus species, Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides species, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Talaromyces marneffei, and Emmonsia species. Because symptoms are frequently non-specific, a high index of suspicion for fungal infection is required for diagnosis. Clinical manifestations of fungal infection + in HIV-infected patients frequently depend on the degree of immunosuppression and the CD4 TH cell count. Establishing definitive diagnosis is important because treatments differ. Primary and + secondary prophylaxis depends on CD4 TH cell counts as well as geographic location and local prevalence of disease. Keywords HIV; Opportunistic Infection; Pneumonia; Mycoses; Pneumocystis The recognition of an outbreak of Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) in 1981 was a fraught moment in the history of medicine.1 It heralded the coming HIV pandemic, a disease heretofore unknown to humankind. Opportunistic fungal pathogens, Pneumocystis jirovecii in particular, have contributed significantly to the morbidity and mortality of HIV-infected patients. -

Appendix: Important Anthroponoses, Zoonoses, and Sapronoses1

CDC - Emerging Human Infectious Diseases: Anthroponoses, Zoonoses, and Sapronoses Appendix: Important Anthroponoses, Zoonoses, and Sapronoses1 Anthroponoses Measles*; rubella; mumps; influenza; common cold; viral hepatitis; poliomyelitis; AIDS*; infectious mononucleosis; herpes simplex; smallpox; trachoma; chlamydial pneumonia and cardiovascular disease*; mycoplasmal infections*; typhoid fever; cholera; peptic ulcer disease*; pneumococcal pneumonia; invasive group A streptococcal infections; vancomycin-resistant enterococcal disease*; meningococcal disease*; whooping cough*; diphtheria*; Haemophilus infections* (including Brazilian purpuric fever*); syphilis; gonorrhea; tuberculosis* (multidrug- resistant strains); candidiasis*; ringworm (Trichophyton rubrum); Pneumocystis pneumonia* (human genotype); microsporidial infections*; cryptosporidiosis* (human genotype); giardiasis* (human genotype); amebiasis; and trichomoniasis. Zoonoses Transmitted by Direct Contact, Alimentary (Foodborne and Waterborne), or Aerogenic (Airborne) Routes Rabies; hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome*; hantavirus pulmonary syndrome*; Venezuelan*; Brazilian*; Argentinian and Bolivian hemorrhagic fevers; Lassa; Marburg; and Ebola hemorrhagic fevers*; Hendra and Nipah hemorrhagic bronchopneumonia*; hepatitis E*; herpesvirus simiae B infection; human monkeypox*;Q fever; sennetsu fever; cat scratch disease; psittacosis; mammalian chlamydiosis*; leptospirosis; zoonotic streptococcosis; listeriosis; erysipeloid; campylobacterosis*; salmonellosis*; hemorrhagic colitis*; -

Global Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of the Endemic Mycoses

1 Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of the Endemic Mycoses 2 George R. Thompson III1, Thuy Le2, Ariya Chindamporn3, Carol A. Kauffman4, Ilan 3 Schwartz5, Ana Alastruey-Izquierdo6, Neil M. Ampel7, David R. Andes8, Darius Armstrong- 4 James9, Olusola Ayanlowo10, John W. Baddley11, Bridget M. Barker12, Leila Lopes Bezerra13, 5 Maria J. Buitrago6, Leili Chamani-Tabriz14, Jasper F.W. Chan15, Methee Chayakulkeeree16, 6 Oliver A. Cornely17, Cao Cunwei18, Jean-Pierre Gangneux19, Nelesh P. Govender20, Ferry Ha- 7 gen21, Mohammad T. Hedayati22, Tobias M. Hohl23, Grégory Jouvion24, Chris Kenyon25, Chris- 8 topher C. Kibbler26, Nikolaj Klimko27, David CM Kong28, Robert Krause29, Low Lee Lee30, 9 Graeme Meintjes31, Marisa H. Miceli32, Peter-Michael Rath33, Andrej Spec34, Flavio Queiroz- 10 Telles35, Ebrahim Variava36, Paul E. Verweij37, Alessandro C. Pasqualotto38 11 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases and the Department of 12 Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of California-Davis Medical Center; 13 Sacramento CA, USA 95817 14 2 Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health, Duke University School of Med- 15 icine, Durham, North Carolina, USA and Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, Ho 16 Chi Minh City, Vietnam 17 3 Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, 18 Thailand 19 4 VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 20 5 Division of Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University -

Fungal Dimorphism and Virulence: Molecular Mechanisms for Temperature Adaptation, Immune Evasion, and in Vivo Survival

Hindawi Mediators of Inflammation Volume 2017, Article ID 8491383, 8 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8491383 Review Article Fungal Dimorphism and Virulence: Molecular Mechanisms for Temperature Adaptation, Immune Evasion, and In Vivo Survival Gregory M. Gauthier Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Gregory M. Gauthier; [email protected] Received 18 November 2016; Accepted 12 April 2017; Published 23 May 2017 Academic Editor: Anamélia L. Bocca Copyright © 2017 Gregory M. Gauthier. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The thermally dimorphic fungi are a unique group of fungi within the Ascomycota phylum that respond to shifts in temperature by ° ° converting between hyphae (22–25 C) and yeast (37 C). This morphologic switch, known as the phase transition, defines the biology and lifestyle of these fungi. The conversion to yeast within healthy and immunocompromised mammalian hosts is essential for virulence. In the yeast phase, the thermally dimorphic fungi upregulate genes involved with subverting host immune defenses. This review highlights the molecular mechanisms governing the phase transition and recent advances in how the phase transition promotes infection. 1. Introduction are more typically phytopathogenic or entomopathogenic. For example, Ophiostoma novo-ulmi, the etiologic agent The ability for fungi to switch between different morphologic of Dutch elm disease, has destroyed millions of elm trees forms is widespread throughout the fungal kingdom and is a in Europe and United States [13].