Appendix: Important Anthroponoses, Zoonoses, and Sapronoses1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fournier's Gangrene Caused by Listeria Monocytogenes As

CASE REPORT Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes as the primary organism Sayaka Asahata MD1, Yuji Hirai MD PhD1, Yusuke Ainoda MD PhD1, Takahiro Fujita MD1, Yumiko Okada DVM PhD2, Ken Kikuchi MD PhD1 S Asahata, Y Hirai, Y Ainoda, T Fujita, Y Okada, K Kikuchi. Une gangrène de Fournier causée par le Listeria Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes as the monocytogenes comme organisme primaire primary organism. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2015;26(1):44-46. Un homme de 70 ans ayant des antécédents de cancer de la langue s’est présenté avec une gangrène de Fournier causée par un Listeria A 70-year-old man with a history of tongue cancer presented with monocytogenes de sérotype 4b. Le débridement chirurgical a révélé un Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b. adénocarcinome rectal non diagnostiqué. Le patient n’avait pas Surgical debridement revealed undiagnosed rectal adenocarcinoma. d’antécédents alimentaires ou de voyage apparents, mais a déclaré The patient did not have an apparent dietary or travel history but consommer des sashimis (poisson cru) tous les jours. reported daily consumption of sashimi (raw fish). L’âge avancé et l’immunodéficience causée par l’adénocarcinome rec- Old age and immunodeficiency due to rectal adenocarcinoma may tal ont peut-être favorisé l’invasion directe du L monocytogenes par la have supported the direct invasion of L monocytogenes from the tumeur. Il s’agit du premier cas déclaré de gangrène de Fournier tumour. The present article describes the first reported case of attribuable au L monocytogenes. Les auteurs proposent d’inclure la con- Fournier’s gangrene caused by L monocytogenes. -

A Review of Outbreaks of Infectious Disease in Schools in England and Wales 1979-88 C

Epidemiol. Infect. (1990), 105, 419-434 419 Printed in Great Britain A review of outbreaks of infectious disease in schools in England and Wales 1979-88 C. JOSEPH1, N. NOAH2, J. WHITE1 AND T. HOSKINS3 'Public Health Laboratory Service, Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre, 61 Colindale Avenue, London NW9 5EQ 2Kings College School o Medicine and Dentistry, Bessemer Road, London SE5 9PJ 3 Christs Hospital, Horsham, Sussex (Accepted 20 May 1990) SUMMARY In this review of 66 outbreaks of infectious disease in schools in England and Wales between 1979-88, 27 were reported from independent and 39 from maintained schools. Altogether, over 8000 children and nearly 500 adults were affected. Most of the outbreaks investigated were due to gastrointestinal infections which affected about 5000 children; respiratory infections affected a further 2000 children. Fifty-two children and seven adults were admitted to hospital and one child with measles died. Vaccination policies and use of immunoglobulin for control and prevention of outbreaks in schools have been discussed. INTRODUCTION The prevention and control of infectious disease outbreaks in schools are important not only because of the number of children at risk but also because of the potential for spread of infection into families and the wider community. Moreover, outbreaks of infection in such communities may lead to serious disruption of children's education and the curtailment of school activities. Details made available of 66 school outbreaks to the Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre between 1979 and 1988 are analysed in this paper and policies for prophylaxis, for example immunoglobulin and vaccination are described. SOURCES OF INFORMATION Information on outbreaks in schools between 1979 and 1988 was obtained from reports of investigations in which the Public Health Laboratory Service (PHLS) Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre (CDSC) had been asked to assist [1] and Communicable Disease Report (CDR) inserts (Table 1). -

Generic Amplification and Next Generation Sequencing Reveal

Dinçer et al. Parasites & Vectors (2017) 10:335 DOI 10.1186/s13071-017-2279-1 RESEARCH Open Access Generic amplification and next generation sequencing reveal Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus AP92-like strain and distinct tick phleboviruses in Anatolia, Turkey Ender Dinçer1†, Annika Brinkmann2†, Olcay Hekimoğlu3, Sabri Hacıoğlu4, Katalin Földes4, Zeynep Karapınar5, Pelin Fatoş Polat6, Bekir Oğuz5, Özlem Orunç Kılınç7, Peter Hagedorn2, Nurdan Özer3, Aykut Özkul4, Andreas Nitsche2 and Koray Ergünay2,8* Abstract Background: Ticks are involved with the transmission of several viruses with significant health impact. As incidences of tick-borne viral infections are rising, several novel and divergent tick- associated viruses have recently been documented to exist and circulate worldwide. This study was performed as a cross-sectional screening for all major tick-borne viruses in several regions in Turkey. Next generation sequencing (NGS) was employed for virus genome characterization. Ticks were collected at 43 locations in 14 provinces across the Aegean, Thrace, Mediterranean, Black Sea, central, southern and eastern regions of Anatolia during 2014–2016. Following morphological identification, ticks were pooled and analysed via generic nucleic acid amplification of the viruses belonging to the genera Flavivirus, Nairovirus and Phlebovirus of the families Flaviviridae and Bunyaviridae, followed by sequencing and NGS in selected specimens. Results: A total of 814 specimens, comprising 13 tick species, were collected and evaluated in 187 pools. Nairovirus and phlebovirus assays were positive in 6 (3.2%) and 48 (25.6%) pools. All nairovirus sequences were closely-related to the Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) strain AP92 and formed a phylogenetically distinct cluster among related strains. -

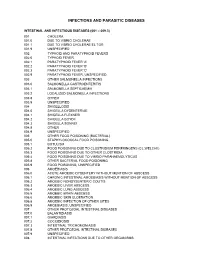

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

Healthcare Providers* Report Immediately by Phone!

Effective July 2008 COMMUNICABLE AND OTHER INFECTIOUS DISEASES REPORTABLE IN MASSACHUSETTS BY HEALTHCARE PROVIDERS* *The list of reportable diseases is not limited to those designated below and includes only those which are primarily reportable by clinical providers. A full list of reportable diseases in Massachusetts is detailed in 105 CMR 300.100. REPORT IMMEDIATELY BY PHONE! This includes both suspect and confirmed cases. All cases should be reported to your local board of health; if unavailable, call the Massachusetts Department of Public Health: Telephone: (617) 983-6800 Confidential Fax: (617) 983-6813 • REPORT PROMPTLY (WITHIN 1-2 BUSINESS DAYS). This includes both suspect and confirmed cases. All cases should be reported to your local board of health; if unavailable, call the Massachusetts Department of Public Health: Telephone: (617) 983-6800 Confidential Fax: (617) 983-6813 • Anaplasmosis • Leptospirosis Anthrax • Lyme disease Any case of an unusual illness thought to have Measles public health implications • Melioidosis Any cluster/outbreak of illness, including but not Meningitis, bacterial, community acquired limited to foodborne illness • Meningitis, viral (aseptic), and other infectious Botulism (non-bacterial) Brucellosis Meningococcal disease, invasive • Chagas disease (Neisseria meningitidis) • Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and variant CJD Monkeypox or other orthopox virus Diphtheria • Mumps • Ehrlichiosis • Pertussis • Encephalitis, any cause Plague • Food poisoning and toxicity (includes poisoning -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

2012 Case Definitions Infectious Disease

Arizona Department of Health Services Case Definitions for Reportable Communicable Morbidities 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Definition of Terms Used in Case Classification .......................................................................................................... 6 Definition of Bi-national Case ............................................................................................................................................. 7 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ............................................... 7 AMEBIASIS ............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 ANTHRAX (β) ......................................................................................................................................................................... 9 ASEPTIC MENINGITIS (viral) ......................................................................................................................................... 11 BASIDIOBOLOMYCOSIS ................................................................................................................................................. 12 BOTULISM, FOODBORNE (β) ....................................................................................................................................... 13 BOTULISM, INFANT (β) ................................................................................................................................................... -

Review Article Fungal Dimorphism and Virulence: Molecular Mechanisms for Temperature Adaptation, Immune Evasion, and in Vivo Survival

Hindawi Mediators of Inflammation Volume 2017, Article ID 8491383, 8 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8491383 Review Article Fungal Dimorphism and Virulence: Molecular Mechanisms for Temperature Adaptation, Immune Evasion, and In Vivo Survival Gregory M. Gauthier Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Gregory M. Gauthier; [email protected] Received 18 November 2016; Accepted 12 April 2017; Published 23 May 2017 Academic Editor: Anamélia L. Bocca Copyright © 2017 Gregory M. Gauthier. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The thermally dimorphic fungi are a unique group of fungi within the Ascomycota phylum that respond to shifts in temperature by ° ° converting between hyphae (22–25 C) and yeast (37 C). This morphologic switch, known as the phase transition, defines the biology and lifestyle of these fungi. The conversion to yeast within healthy and immunocompromised mammalian hosts is essential for virulence. In the yeast phase, the thermally dimorphic fungi upregulate genes involved with subverting host immune defenses. This review highlights the molecular mechanisms governing the phase transition and recent advances in how the phase transition promotes infection. 1. Introduction are more typically phytopathogenic or entomopathogenic. For example, Ophiostoma novo-ulmi, the etiologic agent The ability for fungi to switch between different morphologic of Dutch elm disease, has destroyed millions of elm trees forms is widespread throughout the fungal kingdom and is a in Europe and United States [13]. -

Isolation of Oropouche Virus from Febrile Patient, Ecuador

RESEARCH LETTERS Testing of tissues from vacuum aspiration and from chorionic 5. Driggers RW, Ho CY, Korhonen EM, Kuivanen S, villi sampling revealed that placenta and chorion contained Jääskeläinen AJ, Smura T, et al. Zika virus infection with prolonged maternal viremia and fetal brain abnormalities. Zika virus RNA. Isolation of Zika virus from the karyotype N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2142–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/ cell culture confirmed active viral replication in embryonic NEJMoa1601824 cells. All the tests performed suggest that the spontaneous abortion in this woman was likely associated with a symp- Address for correspondence: Azucena Bardají, ISGlobal, Hospital Clínic, tomatic Zika virus infection occurring early in pregnancy. Universitat de Barcelona, Rosselló, 132, 5-1, 08036 Barcelona, Spain; These findings provide further evidence of the association email: [email protected] between Zika virus infection early in pregnancy and trans- placental infection, as well as embryonic damage, leading to poor pregnancy outcomes (2). Given that embryo loss had probably occurred days before maternal-related symp- toms, we hypothesize that spontaneous abortion happened early during maternal viremia. The prolonged viremia in the mother beyond the first week after symptom onset concurs with other recent reports (1,5). However, persistent viremia 3 weeks after pregnancy outcome has not been described Isolation of Oropouche Virus previously and underscores the current lack of knowledge from Febrile Patient, Ecuador regarding the persistence of Zika virus infection. Because we identified Zika virus RNA in placental tissues, our find- ings reinforce the evidence for early gestational placental Emma L. Wise, Steven T. -

Potential Arbovirus Emergence and Implications for the United Kingdom Ernest Andrew Gould,* Stephen Higgs,† Alan Buckley,* and Tamara Sergeevna Gritsun*

Potential Arbovirus Emergence and Implications for the United Kingdom Ernest Andrew Gould,* Stephen Higgs,† Alan Buckley,* and Tamara Sergeevna Gritsun* Arboviruses have evolved a number of strategies to Chikungunya virus and in the family Bunyaviridae, sand- survive environmental challenges. This review examines fly fever Naples virus (often referred to as Toscana virus), the factors that may determine arbovirus emergence, pro- sandfly fever Sicilian virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic vides examples of arboviruses that have emerged into new fever virus (CCHFV), Inkoo virus, and Tahyna virus, habitats, reviews the arbovirus situation in western Europe which is widespread throughout Europe. Rift Valley fever in detail, discusses potential arthropod vectors, and attempts to predict the risk for arbovirus emergence in the virus (RVFV) and Nairobi sheep disease virus (NSDV) United Kingdom. We conclude that climate change is prob- could be introduced to Europe from Africa through animal ably the most important requirement for the emergence of transportation. Finally, the family Reoviridae contains a arthropodborne diseases such as dengue fever, yellow variety of animal arbovirus pathogens, including blue- fever, Rift Valley fever, Japanese encephalitis, Crimean- tongue virus and African horse sickness virus, both known Congo hemorrhagic fever, bluetongue, and African horse to be circulating in Europe. This review considers whether sickness in the United Kingdom. While other arboviruses, any of these pathogenic arboviruses are likely to emerge such as West Nile virus, Sindbis virus, Tahyna virus, and and cause disease in the United Kingdom in the foresee- Louping ill virus, apparently circulate in the United able future. Kingdom, they do not appear to present an imminent threat to humans or animals. -

Series Fungal Infections 8 Improvement of Fungal Disease

Series Fungal infections 8 Improvement of fungal disease identification and management: combined health systems and public health approaches Donald C Cole, Nelesh P Govender, Arunaloke Chakrabarti, Jahit Sacarlal, David W Denning More than 1·6 million people are estimated to die of fungal diseases each year, and about a billion people have Lancet Infect Dis 2017 cutaneous fungal infections. Fungal disease diagnosis requires a high level of clinical suspicion and specialised Published Online laboratory testing, in addition to culture, histopathology, and imaging expertise. Physicians with varied specialist July 31, 2017 training might see patients with fungal disease, yet it might remain unrecognised. Antifungal treatment is more http://dx.doi.org/10.1016 S1473-3099(17)30308-0 complex than treatment for bacterial or most viral infections, and drug interactions are particularly problematic. See Online/Series Health systems linking diagnostic facilities with therapeutic expertise are typically fragmented, with major elements http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ missing in thousands of secondary care and hospital settings globally. In this paper, the last in a Series of eight papers, S1473-3099(17)30303-1, we describe these limitations and share responses involving a combined health systems and public health framework http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ illustrated through country examples from Mozambique, Kenya, India, and South Africa. We suggest a mainstreaming S1473-3099(17)30304-3, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ approach including greater integration of fungal diseases into existing HIV infection, tuberculosis infection, diabetes, S1473-3099(17)30309-2, chronic respiratory disease, and blindness health programmes; provision of enhanced laboratory capacity to detect http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ fungal diseases with associated surveillance systems; procurement and distribution of low-cost, high-quality antifungal S1473-3099(17)30306-7, medicines; and concomitant integration of fungal disease into training of the health workforce. -

Rat Bite Fever Due to Streptobacillus Moniliformis a CASE TREATED by PENICILLIN by F

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central Rat Bite Fever Due to Streptobacillus Moniliformis A CASE TREATED BY PENICILLIN By F. F. KANE, M.D., M.R.C.P.I., D.P.H. Medical Superintendent, Purdysburn Fever Hospital, Belfast IT is unlikely that rat-bite fever will rver become a public health problem in this country, so the justification for publishing the following case lies rather in its rarity, its interesting course and investigation, and in the response to Penicillin. PRESENT CASE. The patient, D. G., born on 1st January, 1929, is the second child in a family of three sons and one daughter of well-to-do parents. There is nothing of import- ance in the family history or the previous history of the boy. Before his present illness he was in good health, was about 5 feet 9j inches in height, and weighed, in his clothes, about 101 stone. The family are city dwellers. On the afternoon of 18th March, 1944, whilst hiking in a party along a country lane about fifteen miles from Belfast city centre, he was bitten over the terminal phalanx of his right index finger by a rat, which held on until pulled off and killed. The rat was described as looking old and sickly. The wound bled slightly at the time, but with ordinary domestic dressings it healed within a few days. Without missing a day from school and feeling normally well in the interval, the boy became sharply ill at lunch-time on 31st March, i.e., thirteen days after the bite.