Resurrecting the Sacred Land of Japan the State of Shinto in the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

The Shrine : Notes toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo By A.W. S a d l e r Sarah Lawrence College When I arrived in Japan in the autumn of 1965, I settled my family into our home-away-from-home in a remote comer of Bunkyo-ku3 in Tokyo, and went to call upon an old timer,a man who had spent most of his adult life in Tokyo. I told him of my intention to carry out an exhaustive study of the annual festivals (taisai) of a typical neighbor hood shrine (jinja) in my area of residence,and I told him I had a full year at my disposal for the task. “Start on the grounds of the shrine/,was his solid advice; “go over every tsubo '(every square foot3 we might say),take note of every stone, investigate every marker.” And that is how I began. I worked with the shrines closest to home so that shrine and people would be part of my everyday life. When my wife and I went for an evening stroll, we invariably happened upon the grounds of one of our shrines; when we went to the market for fish or pencils or raaisnes we found ourselves visiting with the ujiko (parishioners; literally,children of the god of the shrine, who is guardian spirit of the neighborhood) of the shrine. I started with five shrines. I had great difficulty arranging for interviews with the priests of two of the five (the reasons for their reluc tance to visit with me will be discussed below) ; one was a little too large and famous for my purposes,and another was a little too far from home for really careful scrutiny. -

Etiquette Inside the Jingu Precinct How to Worship Kami Naiku Is The

Kodenchi (Site of the previous sanctuary) 古殿地 Main sanctuary A divine palace of Amaterasu-Omikami stands here. The Holy Mirror (a symbol of Amaterasu-Omikami) is enshrined inside the main sacred palace at the innermost courtyard of the main sanctuary and the main palace is enclosed with four rows of Naiku is the most venerable sanctuary in Japan. Here is a jinja (Shinto shrine) wooden fences. Pilgrims usually worship the enshrined kami in dedicated to Amaterasu-Omikami, the ancestral kami (Shinto deity) of the Imperial front of the gate of the third row of the fence. family. She was enshrined in Naiku about 2,000 years ago and has been revered as a guardian of Japan. Aramatsuri-no-miya There are 14 superior affiliated jinja which are revered next to the main sanctuaries of Naiku and Geku in Jingu. This jinja occupies the highest rank among them and is dedicated to a vigorous spirit of Geheiden Amaterasu-Omikami. (outer treasury) One of the auxiliary jinja of Naiku to store harvested rice for 外幣殿 offering to kami in rituals. An architectural style of this jinja is similar to that of the main palace of the main sanctuary but smaller in size. It is said that the style of jinja in Jingu derived from rice granary Jingu is a sanctuary to pray for public of ancient Japan. happiness. If someone have personal wish, he or she can dedicate a prayer by offering kagura (ceremonial music Kazahinomi-no-miya Rest house for Pilgrims. and dance) to kami of Jingu. Amulets Souvenirs and drink vending One of the superior affiliated jinja dedicated to a couple of Jingu can be obtained here. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90w6w5wz Author Carter, Caleb Swift Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Caleb Swift Carter 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries by Caleb Swift Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor William M. Bodiford, Chair This dissertation considers two intersecting aspects of premodern Japanese religions: the development of mountain-based religious systems and the formation of numinous sites. The first aspect focuses in particular on the historical emergence of a mountain religious school in Japan known as Shugendō. While previous scholarship often categorizes Shugendō as a form of folk religion, this designation tends to situate the school in overly broad terms that neglect its historical and regional stages of formation. In contrast, this project examines Shugendō through the investigation of a single site. Through a close reading of textual, epigraphical, and visual sources from Mt. Togakushi (in present-day Nagano Ken), I trace the development of Shugendō and other religious trends from roughly the thirteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries. This study further differs from previous research insofar as it analyzes Shugendō as a concrete system of practices, doctrines, members, institutions, and identities. -

Turystyka Kulturowa. Czasopismo Naukowe

ISSN 1689-4642 Spis treści Artykuły ............................................................................................................. 7 Joanna Kowalczyk-Anioł, Ali Afshar Gentryfikacja turystyczna jako narzędzie rozwoju miasta. Przykład Meszhed w Iranie ....... 7 Rafał G. Nowicki Partycypacja turystów i mieszkańców miejscowości turystycznych w procesie ochrony zabytków architektury....................................................................................................... 26 Andrzej Moniak, Michał Suszczewicz Przestrzeń kulturowa i niechciane dziedzictwo garnizonów poradzieckich na pograniczu Polski i Niemiec ............................................................................................................... 40 Petr Bujok, Martin Klempa, Dominik Niemiec, Jakub Ryba, Michal Porzer Dziedzictwo przemysłowe firmy „Baťa” w mieście Zlín (Republika Czeska) ................... 54 Małgorzata Gałązka, Monika Gałązka Shintō jako walor turystyczny ........................................................................................... 67 Joanna Roszak, Grzegorz Godlewski Chronotop Lubelszczyzny. Ocena atrakcyjności regionu dla turystyki literackiej z wykorzystaniem bonitacji punktowej ............................................................................. 85 Nikoloz Kavelashvili Protecting the Past for Today: Development of Georgia’s Heritage Tourism ..................... 97 Recenzja ......................................................................................................... 110 Czajkowski Szymon -

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Patricia Shehan Campbell, Chair Jeffrey M. Perl Christina Sunardi Paul S. Atkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ii ©Copyright 2017 Michiko Urita iii University of Washington Abstract In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Patricia Shehan Campbell Music This dissertation explores the essence and resilience of the most sacred and secret ritual music of the Japanese imperial court—kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku—by examining ways in which these two songs have survived since their formation in the twelfth century. Kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku together are the jewel of Shinto ceremonial vocal music of gagaku, the imperial court music and dances. Kagura secret songs are the emperor’s foremost prayer offering to the imperial ancestral deity, Amaterasu, and other Shinto deities for the well-being of the people and Japan. I aim to provide an understanding of reasons for the continued and uninterrupted performance of kagura secret songs, despite two major crises within Japan’s history. While foreign origin style of gagaku was interrupted during the Warring States period (1467-1615), the performance and transmission of kagura secret songs were protected and sustained. In the face of the second crisis during the Meiji period (1868-1912), which was marked by a threat of foreign invasion and the re-organization of governance, most secret repertoire of gagaku lost their secrecy or were threatened by changes to their traditional system of transmissions, but kagura secret songs survived and were sustained without losing their iv secrecy, sacredness, and silent performance. -

Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii

The Japanese and Okinawan American Communities and Shintoism in Hawaii: Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʽI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2012 By Sawako Kinjo Thesis Committee: Dennis M. Ogawa, Chairperson Katsunori Yamazato Akemi Kikumura Yano Keywords: Japanese American Community, Shintoism in Hawaii, Izumo Taishayo Mission of Hawaii To My Parents, Sonoe and Yoshihiro Kinjo, and My Family in Okinawa and in Hawaii Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my deep and sincere gratitude to my committee chair, Professor Dennis M. Ogawa, whose guidance, patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge have provided a good basis for the present thesis. I also attribute the completion of my master’s thesis to his encouragement and understanding and without his thoughtful support, this thesis would not have been accomplished or written. I also wish to express my warm and cordial thanks to my committee members, Professor Katsunori Yamazato, an affiliate faculty from the University of the Ryukyus, and Dr. Akemi Kikumura Yano, an affiliate faculty and President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Japanese American National Museum, for their encouragement, helpful reference, and insightful comments and questions. My sincere thanks also goes to the interviewees, Richard T. Miyao, Robert Nakasone, Vince A. Morikawa, Daniel Chinen, Joseph Peters, and Jikai Yamazato, for kindly offering me opportunities to interview with them. It is a pleasure to thank those who made this thesis possible. -

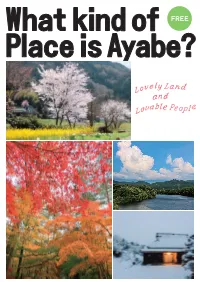

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

HIRATA KOKUGAKU and the TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon

SPIRITS AND IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NORTHEASTERN JAPAN: HIRATA KOKUGAKU AND THE TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon Fujiwara A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gideon Fujiwara, 2013 ABSTRACT While previous research on kokugaku , or nativism, has explained how intellectuals imagined the singular community of Japan, this study sheds light on how posthumous disciples of Hirata Atsutane based in Tsugaru juxtaposed two “countries”—their native Tsugaru and Imperial Japan—as they transitioned from early modern to modern society in the nineteenth century. This new perspective recognizes the multiplicity of community in “Japan,” which encompasses the domain, multiple levels of statehood, and “nation,” as uncovered in recent scholarship. My analysis accentuates the shared concerns of Atsutane and the Tsugaru nativists toward spirits and the spiritual realm, ethnographic studies of commoners, identification with the north, and religious thought and worship. I chronicle the formation of this scholarly community through their correspondence with the head academy in Edo (later Tokyo), and identify their autonomous character. Hirao Rosen conducted ethnography of Tsugaru and the “world” through visiting the northern island of Ezo in 1855, and observing Americans, Europeans, and Qing Chinese stationed there. I show how Rosen engaged in self-orientation and utilized Hirata nativist theory to locate Tsugaru within the spiritual landscape of Imperial Japan. Through poetry and prose, leader Tsuruya Ariyo identified Mount Iwaki as a sacred pillar of Tsugaru, and insisted one could experience “enjoyment” from this life and beyond death in the realm of spirits. -

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What Is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura This ritual dance is performed to purify the kagura site, with the performer carrying a Since ancient times, people in Japan have believed torimono (prop) while remaining unmasked. Various props are carried while the dance is that gods inhabit everything in nature such as rocks and History of Izumo Kagura Shichiza performed without wearing any masks. The name shichiza is said to derive from the seven trees. Human beings embodied spirits that resonated The Shimane Prefecture is a region which boasts performance steps that comprise it, but these steps vary by region. and sympathized with nature, thus treasured its a flourishing, nationally renowned kagura scene, aesthetic beauty. with over 200 kagura groups currently active in the The word kagura is believed to refer to festive prefecture. Within Shimane Prefecture, the regions of rituals carried out at kamikura (the seats of gods), Izumo, Iwami, and Oki have their own unique style of and its meaning suggests a “place for calling out and kagura. calming of the gods.” The theory posits that the word Kagura of the Izumo region, known as Izumo kamikuragoto (activity for the seats of gods) was Kagura, is best characterized by three parts: shichiza, shortened to kankura, which subsequently became shikisanba, and shinno. kagura. Shihoken Salt—signifying cleanliness—is used In the first stage, four dancers hold bells and hei (staffs with Shiokiyome paper streamers), followed by swords in the second stage of Sada Shinno (a UNESCO Intangible Cultural (Salt Purification) to purify the site and the attendees. -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice.