First Class: a Guide for Early Primary Education. Preschool-Kindergarten-First Grade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Y4Q1 --Rise of England -- Reader Daniel 1.0.0.Indd

Rise of England Old Western Culture Reader Volume 13 Rise of England Old Western Culture Reader Volume 13 Companion to Early Moderns: Rise of England, a great books curriculum by Roman Roads Press MOSCOW, IDAHO Rise of England: Old Western Culture Reader, Volume 13 Copyright © 2019 Roman Roads Press Published by Roman Roads Press Moscow, Idaho romanroadsmedia.com Series Editor Daniel Foucachon Paradise Lost Editor: Claire Escalante Cover Design: Valerie Anne Bost, Daniel Foucachon, and Rachel Rosales Interior Layout: Valerie Anne Bost Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by the USA copyright law. Rise of England: Old Western Culture Reader, Volume 13 Roman Roads Press is an imprint of Roman Roads Media, LLC ISBN: 978-1-944482-47-3 (paperback) Version 1.0.0 2019 This is a companion reader for the Old Western Culture curriculum by Roman Roads Press. To find out more about this course, visit www.romanroadspress.com. Old Western Culture Great Books Reader Series THE GREEKS VOLUME 1 The Epics VOLUME 2 Drama & Lyric VOLUME 3 The Histories VOLUME 4 The Philosophers THE ROMANS VOLUME 5 The Aeneid VOLUME 6 The Historians VOLUME 7 Early Christianity VOLUME 8 Nicene Christianity CHRISTENDOM VOLUME 9 Early Medievals VOLUME 10 Defense of the Faith VOLUME 11 The Medieval Mind VOLUME 12 The Reformation EARLY MODERNS VOLUME 13 Rise of England VOLUME 14 Poetry and Politics VOLUME 15 The Enlightenment VOLUME 16 The Novels CONTENTS William Shakespeare Selected Sonnets. -

PUFFIN BOOKS by ROALD DAHL the BFG Boy: Tales of Childhood

PUFFIN BOOKS BY ROALD DAHL The BFG Boy: Tales of Childhood Charlie and the Chocolate Factory Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator Danny the Champion of the World Dirty Beasts The Enormous Crocodile Esio Trot Fantastic Mr. Fox George's Marvelous Medicine The Giraffe and the Pelly and Me Going Solo James and the Giant Peach The Magic Finger Matilda The Minpins Roald Dahl's Revolting Rhymes The Twits The Vicar of Nibbleswicke The Witches The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Six More ROALD DAHL The BFG ILLUSTRATED BY QUENTIN BLAKE PUFFIN BOOKS For Olivia 20 April 1955—17 November 1962 PUFFIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1982 First published in the United States of America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1982 Published in Puffin Books, 1984 Reissued in this Puffin edition, 1998 7 9 10 8 6 Text copyright © Roald Dahl, 1982 Illustrations copyright © Quentin Blake, 1982 All rights reserved THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PREVIOUS PUFFIN BOOKS EDITION UNDER CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 85-566 This edition ISBN 0-14-130105-8 Printed in the United States of America Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Le Breakfast Le Brunch Le Lunch Welcome to Le Peep! We Hope You’Ll Enjoy Our Legendary Breakfast Dishes and Savory Lunch Creations

A great way to start the day! Le Breakfast Le Brunch Le Lunch Welcome to Le Peep! We hope you’ll enjoy our legendary breakfast dishes and savory lunch creations. With over fifty locations, Le Peep is known for abundant flavors and generous servings. Le Peep Valparaiso is locally owned by the Costas family. Fresh, simple and elegant, Le Peep is Valparaiso’s most preferred breakfast and lunch destination. Breakfast Homespun Pancakes Beginnings Plain Cakes 5.19 Cookie Cakes 6.49 Our signature batter is the best! Two cakes filled with chocolate chips and Start off right with the Homemade and delicious. crunchy, sweet granola. most important meal of the day! 6.49 6.99 ™ 3.49 Blueberry Banana Walnut Gooey Buns Two cakes chock full of plump blueberries. Go bananas & walnuts over these two cakes! An English muffin broiled with brown sugar, cinnamon and almonds. Served with cream cheese and “Mom’s Sassy Apples®.” Wheat 6.49 Almond Cranberry 6.29 Health conscious? Try our cakes with sweet Sweet & nutty almonds with tart cranberries in Pancake Sandwich 6.29 wheat germ. our homemade pancake batter. One egg and two mini pancakes. Served with two bacon strips, whipped butter and syrup. Granola Blues 6.99 Fruit Cakes 6.89 Blueberries and granola... what else could you Wheat germ cakes topped with “Mom’s Sassy Le Petit Toast 6.29 ask for? Apples®”, blueberries, strawberries, bananas & Two custard battered pieces of French Toast a sprinkle of powdered sugar. sprinkled with powdered sugar and served with two bacon strips. Le Egg Sandwich 5.29 Le French Toast & Waffles One scrambled egg, two bacon strips, & cheese on your choice of bread with Peasant Potatoes®. -

The Life of Sir Richard Burton

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com .B97 THE LIFE OF SIR RICHARD BURTON LADY BURTON. Photo by Gunn & Stuart Richmond Surrey. THE LIFE OF SIR RICHARD BURTON THOMAS WRIGHT AUTHOR OF "THE LIFE OF EDWARD FITZGERALD." ETC. WITH SIXTY-FOUR PLATES. TWO VOLUMES VOL. II LONDON EVERETT & CO. 1906 (All Rights Reserved.) #4. //- it>- 3L $ tX CONTENTS OF VOLUME II CHAPTER XXI' 27th December 1879 — August 1881 CAMOENS^ 98. The Lusiads - - - - - -13 99. Ober Ammergau - - - - 16 100. Mrs. Burton's Advice to Novelists - - 19 101. The Kasidah - - - - - - 20 102. Lisa - _- -.-.23 CHAPTER XXII August 1 88 1 — 20th May 1882 JOHN PAYNE 103. With Cameron at Venice, August 1881 - - 25 104. John Payne, November 1881 - - - 26 105. To the Gold Coast, 25th November 1881 — 20th May 1882 34 CHAPTER XXIII., 20th May 1882— July 1883 THE MEETING OF BURTON AND PAYNE 106. Mrs. Grundy begins to Roar, May 1882 - - - 37 107. The Search lor Palmer, October 1882 - - - 43 CHAPTER XXIV July 1883 — November 1883 THE PALAZZONE 108. Anecdotes of Burton - 46 109. Burton and Mrs. Disraeli 47 110. "I am an Old English Catholic ' ' 49 111. Burton begins his Translation, April 1884 S2 1 1 2. The Battle over the Nights 54 113. Completion of Payne's Translation 56 vi LIFE OF SIR RICHARD BURTON CHAPTER XXV THE KAMA SHASTRA SOCIETY 114. The Azure Apollo - 57 115. The Kama Sutra - - - 63 CHAPTER XXVI "THE ANANGA RANGA " 1885 116. -

Bobcat Invite

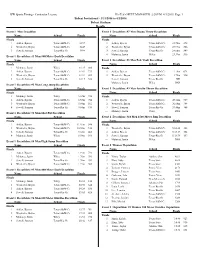

BW Sports Timing - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 2:20 PM 4/3/2016 Page 1 Bobcat Invitational - 3/31/2016 to 4/2/2016 Bobcat Stadium Results Event 1 Men Decathlon Event 1 Decathlon: #7 Men Discus Throw Decathlon Name School Finals Name School Finals Finals Finals 1 Adden, Bjoern Texas A&M-Cc 6157 1 Adden, Bjoern Texas A&M-Cc 31.70m 498 2 Wersterfer, Bryan Texas A&M-Cc 5443 2 Wersterfer, Bryan Texas A&M-Cc 25.97m 386 3 Sewell, Samson Texas-Rio Gr 3994 3 Sewell, Samson Texas-Rio Gr 24.08m 349 4 Maloney, Justin Wiley 23.39m 336 Event 1 Decathlon: #1 Men 100 Meter Dash Decathlon Name School Finals Event 1 Decathlon: #8 Men Pole Vault Decathlon Finals Name School Finals 1 Maloney, Justin Wiley 11.25 806 Finals 2 Adden, Bjoern Texas A&M-Cc 11.64 723 1 Adden, Bjoern Texas A&M-Cc 4.19m 671 3 Wersterfer, Bryan Texas A&M-Cc 11.84 683 2 Wersterfer, Bryan Texas A&M-Cc 3.74m 546 4 Sewell, Samson Texas-Rio Gr 12.15 622 --- Sewell, Samson Texas-Rio Gr NH --- Maloney, Justin Wiley DNS Event 1 Decathlon: #2 Men Long Jump Decathlon Name School Finals Event 1 Decathlon: #9 Men Javelin Throw Decathlon Finals Name School Finals 1 Maloney, Justin Wiley 6.67m 736 Finals 2 Adden, Bjoern Texas A&M-Cc 6.53m 704 1 Adden, Bjoern Texas A&M-Cc 45.12m 517 3 Wersterfer, Bryan Texas A&M-Cc 5.88m 561 2 Wersterfer, Bryan Texas A&M-Cc 36.00m 384 4 Sewell, Samson Texas-Rio Gr 5.68m 519 3 Sewell, Samson Texas-Rio Gr 33.46m 348 --- Maloney, Justin Wiley DNS Event 1 Decathlon: #3 Men Shot Put Decathlon Name School Finals Event 1 Decathlon: #10 Men 1500 Meter Run Decathlon -

2019 Unclaimed Property Report

NOTICE TO OWNERS OF ABANDONED PROPERTY: 2019 UNCLAIMED PROPERTY REPORT State Treasurer John Murante 402-471-8497 | 877-572-9688 treasurer.nebraska.gov Unclaimed Property Division 809 P Street Lincoln, NE 68508 Dear Nebraskans, KUHLMANN ORTHODONTICS STEINSLAND VICKI A WITT TOM W KRAMER TODD WINTERS CORY J HART KENNETH R MOORE DEBRA S SWANSON MATHEW CLAIM TO STATE OF NEBRASKA FOR UNCLAIMED PROPERTY Reminder: Information concerning the GAYLE Y PERSHING STEMMERMAN WOLFE BRIAN LOWE JACK YOUNG PATRICK R HENDRICKSON MOORE KEVIN SZENASI CYLVIA KUNSELMAN ADA E PAINE DONNA CATHERNE COLIN E F MR. Thank you for your interest in the 2019 Property ID Number(s) (if known): How did you become aware of this property? WOODWARD MCCASLAND TAYLORHERDT LIZ “Claimant” means person claiming property. amount or description of the property and LARA JOSE JR PALACIOS AUCIN STORMS DAKOTA R DANNY VIRGILENE HENDRICKSON MULHERN LINDA J THOMAS BURDETTE Unclaimed Property Newspaper Publication BOX BUTTE Unclaimed Property Report. Unclaimed “Owner” means name as listed with the State Treasurer. LE VU A WILMER DAVID STORY LINDA WURDEMAN SARAH N MUNGER TIMOTHY TOMS AUTO & CYCLE Nebraska State Fair the name and address of the holder may PARR MADELINE TIFFANY ADAMS MICHAEL HENZLER DEBRA J property can come in many different Husker Harvest Days LEFFLER ROBERT STRATEGIC PIONEER BANNER MUNRO ALLEN W REPAIR Claimant’s Name and Present Address: Claimant is: LEMIRAND PATTNO TOM J STREFF BRIAN WYMORE ERMA M BAKKEHAUG HENZLER RONALD L MURPHY SHIRLEY M TOOLEY MICHAEL J Other Outreach -

Sizzling Deals Start Dec. 10 $5 Bacon Dishes Monday, Dec

SIZZLING DEALS START DEC. 10 $5 BACON DISHES MONDAY, DEC. 10 - SUNDAY, DEC. 16 | HOW MANY CAN YOU CHECK OFF? 317 BURGER fresh Roma tomatoes, creamy ranch BROTHERS BAR & GRILL dressing, more bacon & scallions. PUNCH BURGER SHOEFLY PUBLIC HOUSE 317burger.com brothersbar.com punchburger.com shoeflypublichouse.com 915 E. Westfield Blvd. 910 Broad Ripple Ave. Dine-in Only 137 E Ohio St. 122 E. 22nd St. Ask for the Indy Bacon Week Special 255 S. Meridian St. Check out our weekly round-up of 12525 Old Meridian St., #100, Sweet & Sour Bacon Tacos Carmel Ask for the Indy Bacon Week Special different specials every night! Ask for the Indy Bacon Week Special 2 sweet & sour glazed bacon tacos with BEARCATS RESTAURANT pickled pepper & napa slaw. & BAR HARVEY’S TAVERN BUB’S BURGERS harveystavern.com Dine-in Only bearcatsindy.com REDEMPTION ALEWERKS & ICE CREAM 614 Main St., Beech Grove 1045 N. Senate Ave. redemptionalewerks.com bubsburgers.com 7035 E. 96th St., Suite K STACKED PICKLE Bacon American Burger 210 W. Main St., Carmel Fried Green Tomato BLT Bacon Beer Cheese Tater Tots stackedpickle.com Cheeseburger with American cheese and 620 S. Main St., Zionsville Thick cut Bacon on Sourdough bread 910 W. 10th St. 480 N. Morton St., Bloomington with fried green tomato, mozzarella Beer Cheese made with queso, blue bacon on bun. Deluxe (Lettuce, Tomato & 7040 McFarland Blvd. Onion) available for 50¢ more. cheese and lettuce. cheese, parmesan & cream cheese Stuffed Bacon & Cheddar Mini Bub blended together with fresh garlic, 172 Melody Ave., Greenwood Bacon Swiss Grilled Bacon Grilled Cheese Bub’s Mini Bub Burger stuffed with Salvation Honey Wheat beer, cayenne 12545 Old Meridian St., Chicken Sandwich Bacon and Cheddar Cheese. -

Grand View Burial Listing.Xlsx

Location Space First Name Middle Last Burial Date D-025-003-013 1 Baby Abbot HH-N-179 1 Harlan Abbott 5/15/2010 HH-N-188 1 Frances Wann Abbott HH-N-093 2 Edson D. Abbott HH-N-093 1 Flora M. Wann Abbott B-006-001 1 M. Alta Abrams B-006-002 1 Henry H. Abrams B-010-009 1 Sara K. Achson D-035-006 1 William Allan Acock D-020-013 1 Richard Acton D-020-014 1 Laura E. Acton A-041-003 1 Julias Adam A-014-001 1 Karjala Adam 6/21/1958 A-012-014 1 Oriel Adams C-024-005 1 Zoe Adams A-010-003 1 Clara A. Adams 5/6/1964 GVA-056-M 1 John L. Adams A-011-004 1 Gerald D. Adams A-010-004 1 Joseph J. Adams GVA-056-N 1 Helen T. Adams 8/26/1981 A-027-009 1 Joseph Adams A-011-003 1 Ophelia Adams GVA-120-G 1 Delmar Adams 9/3/1968 A-012-013 1 Harry Adams CV-EAS-054 1 Alta Adams C-043-016 1 George D. Ahrens HH-N-119 1 Mary Albaugh HH-N-119 2 Edgar S. Albaugh GVA-209-B 1 Daniel Aldridge A-013-003 1 Nancy Algord D-003-008 1 Mary Beglie Allan D-003-012 1 Martha Allan 11/24/1967 D-003-007 1 Archibold Allan 9/21/1953 D-003-006 1 Julia Lillian Allan 5/1/1951 GVA-050-L 1 Evelyn I. -

The Archives of the University of Notre Dame

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus ^HE NOTRE DAME ALUMNUS i v.a S^4^E,.v0v^ IN THIS ISSUE Nieuwiand Foundation Notre Dame's 96th Vear Faculty Changes Spotlight Alumni Football Season Campus News Club News Class News THE STADIUM 1. 16 October, 1937 No. 1 AGAINI FRIDAY NIGHT ON m ^'^ OCT. 151 PONTIACS FAMOUS SHOW 4N AUTHENTIC CKOSS-SKTION OF THE FINEST TALENT OF AMERICA'S GREAT UNIVERSITIES BROADCAST DIRECT FROM THE CANIPUS OF EACH SCHOOL At the request of University alumni and students all over the country, and of the general public, Pontiac, builder of the Silver Streak Six and Eight, will continue to produce "Varsity Show," the radio sensation of last winter and spring. An entirely new list of colleges will be given an opportunity to display their finest musical and dramatic talent in shows ;^; iocal ne»-spaper for just as interesting and lively as those that won America before. Opened by the University of Alabama, followed by Purdue, Southern Methodist, Virginia, Fordham, and Indiana, among many others, the new series can be counted upon to give you again "the gayest show on the air." PRESENTED BY- BUILDER OF AMERICA'S FINEST LOW-PRICED CAR 1^7/3f V. 1^ The Notre Dame Alumnus JAMES E, ARMSTRONG. "25 The mnjmzine is published from October to June inclusive by the Alumni Association Member of (he American of the University of Notre Dame. Notre Dame, Indiana. The subscription price is S2.00 Editor a year; the price of sincle copies is 25 cents. -

County's One-Sort Recycling Proposal Discussed at City Council Meeting

Single copy $1.00 Vol. 113 No. 1 • Thursday, December 26, 2013 • Silver Lake, MN 55381 Molly’s owner seeks licenses to sell alcohol; Council balks By Alyssa Schauer April with the state, instead of icy, which already includes li- Staff Writer at the first of the year, no mat- censing for liquor. Frank Koelfgen, owner of ter when you apply for the li- “I guess I have a hard time Molly’s Cafe, met with the cense,” Koelfgen said. giving out a liquor license Silver Lake City Council at its “To keep the license re- with a municipal and a Legion regular meeting Dec. 16 to newal on par with the city, one Club in town,” Bebo said. discuss options for serving and thing I would ask of the city is “It’s just something I selling alcohol at his establish- to waive that $250 for three thought about today. I added ment. months,” Koelfgen said. off-sale as more of a service to For a few years, Koelfgen He said he wanted to be able customers, but 3.2 beer has a said he has had a 3.2 beer li- to “get going” on the license stigma with people, and I cense for on-sale and off-sale, for the holiday season, but did- thought it’d be nice to have and last year, he applied for a n’t really want to spend $500, stuff on hand,” Koelfgen said. wine license, but never re- only to pay $500 again in three Bebo again questioned ceived it from the state of months to renew the license. -

The Ledger and Times, February 25, 1966

Murray State's Digital Commons The Ledger & Times Newspapers 2-25-1966 The Ledger and Times, February 25, 1966 The Ledger and Times Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt Recommended Citation The Ledger and Times, "The Ledger and Times, February 25, 1966" (1966). The Ledger & Times. 5293. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt/5293 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ledger & Times by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •••••• • • ••••••••$ 4 'a ro • ...&..i'•,• 1966 $ Milt Paducah JC Bill Dead; Murray State Is Now A University bran- such a rate only with written In other action Thursday, the By DREW VON MERMEN It allows Eastern, Western, More- Charges of arm-twisting by Gov. kill the bill. arson. could have made the Pelages lows University of Kentucky. agreement. Senate: United Press Inbernationse head, and Murray state colleges to Edward T. Breathitt were aired on After the amendment had been Wetherby told the &hate it ches of the conceded, however, that the The Senate was sharply divided —Defeated a bill outlawing flav- FRANKFORT, Ky. I — The become universities. the Senate floor. However, Sen. approved, a quick roll call was would be the "mat expensive bill He revised constitution, currently be- on the bill. ored aspirin pills. state Senate reversed lama today The Senate switch came after • J. D. Buckman, D-floor leader, said made on the bill itaelf, and it pas- In the state of Kentucky,' adding considered for adoption, would -It will help create a more —Defeated a measure prohibit- and eliminated an amencknent series of parlamentary motiona that the rider had to be deleted sed 32-5. -

The Hen House

PEPPERWOOD VILLAGE 559 North 155th Plaza, Omaha, NE 68154 | 402-408-1728 LEGACY 17660 Wright Street, Omaha, NE 68130 | 402-934-9914 NORTH PARK 2012 North 117th Ave, Omaha, NE 68164 | 402-991-8222 AKSARBEN POINTE 6920 Pacific Street, Omaha, NE 68106 | 402-933-2776 LePeepOmaha.com BREAKFAST BEGINNINGS HOT OFF THE GRIDDLE ™ Home Spun Pancakes Gooey Buns A LePeep Specialty! English muffin broiled with cinnamon, As a “Batter of Fact,” we introduced these ultra-light cakes in 1963, in Aspen, CO. brown sugar, toasted almonds, cream cheese and Mom’s Sassy Apples®. 4.99 (CAL: 528) 2 cakes made with Le Peep’s homemade batter. Cinnamon Roll 5.49 (CAL: 700) By May we suggest either (2) links of sausage or (2) strips of bacon & Aspen Fruit Crepes Crepes filled with fresh strawberries and a rich, ricotta and (2)* eggs to go with your Pancakes or French toast. Add 4.29 (CAL: 321-994) cream cheese filling with a touch of citrus zest. Topped with strawberries, powdered Plain 6.79 (CAL: 913) Blueberry 8.79 (CAL: 977) sugar and whipped cream. Le Delicious! 8.79 (CAL: 903-984) Blueberry Granola 8.99 (CAL: 1446) Banana Walnut 8.99 (CAL: 1389) Breakfast Banana Split Noosa™ organic honey yogurt topped with bananas, Lemon Ricotta Blues 8.99 (CAL: 1455) Cinnamon Roll Cakes 8.99 (CAL: 1385) strawberries, blueberries and granola. 7.49 (CAL: 361) Nutella Crepes Delicate French crepes filled with nutty chocolate Nutella®. Topped with your choice of fresh fruit and a dusting of powdered sugar. 8.79 (CAL: 453) Add * (2) eggs and bacon or sausage 4.29 (CAL: 321-944) pancake of the month Berry Nutty Oatmeal Topped with strawberries, blueberries, bananas, walnuts, almonds and a drizzle of agave nectar, served with Gooey Buns or a bagel Each month we feature a Signature Pancake.