The Murrow Tradition: What Was It, and Does It Still Live?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future

Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future By Daniel R. Bersak S.B. Comparative Media Studies & Electrical Engineering/Computer Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2003 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER, 2006 Copyright 2006 Daniel R. Bersak, All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _____________________________________________________ Department of Comparative Media Studies, August 11, 2006 Certified By: ___________________________________________________________ Edward Barrett Senior Lecturer, Department of Writing Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: __________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Director Ethics In Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future By Daniel R. Bersak Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies, School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences on August 11, 2006, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract Like writers and editors, photojournalists are held to a standard of ethics. Each publication has a set of rules, sometimes written, sometimes unwritten, that governs what that publication considers to be a truthful and faithful representation of images to the public. These rules cover a wide range of topics such as how a photographer should act while taking pictures, what he or she can and can’t photograph, and whether and how an image can be altered in the darkroom or on the computer. -

Summer 2008, Vol. II, Issue 2

RRIIVVEERR TTAALLKK Summer 2008 Summer 2008 THE MINNESOTA RIVER CURRENT Vol. II Is sue 2 “““BBBIIIGGG SSSTTTOOONNNEEE IIIIII CCCOOOAAALLL PPPLLLAAANNNTTT””” Introduction Scott Sparlin, Executive Director of the Not only has the proposed construction Coalition for a Clean Minnesota River spoke of the Big Stone II power plant, located across passionately about the Minnesota River and the from Ortonville in South Dakota, stirred up a consequences on water resources. debate on how each of us looks at the Minnesota “Since 1989, we’ve worked hard to River but also how this coal-generated plant educate and raise awareness about the condition could affect our daily life. of the Minnesota River. Together with our Citizens, legislators and organizations significant partners in business, government, and are concerned about the plant’s impact on the nonprofit sector, we have achieved numerous reducing water flow from the Big Stone Lake, successes and have met challenges head on in increasing mercury pollution and our standard of our efforts to heal and improve water in the living here in the Minnesota River Watershed. Minnesota basin.” For those on the other end of the spectrum, Big Stone II represents economic “Reconvene the development and stable electrical prices. Local MN / SD businesses, unions and power companies see the Boundary Waters plant providing high wage jobs and a way to Commission. meet rising energy demands. Can we talk this Emotion has run high on both sides as through with our good neighbor? people express their view points on climate change, water quality and alternative energy I’m sure they have a sources including wind generation. -

Bibliography of Recent Books in Communications Law

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RECENT BOOKS IN COMMUNICATIONS LAW Patrick J. Petit* The following is a selective bibliography of re- the United States, Germany, and the European cent books in communications law and related Convention on Human Rights. Chapter 1 dis- fields, published in late 1996 or 1997. Each work cusses the philosophical underpinnings of the is accompanied by an annotation describing con- right of privacy; Chapter 2 explores the history of tent and focus. Bibliographies and other useful the development of the right in each of the three information in appendices are also noted. systems. Subsequent chapters examine the struc- ture, coverage, protected scope, content, and who are the subjects of the right to secrecy in telecom- FREEDOM OF PRESS AND SPEECH munications. An extensive bibliography and table of cases is provided. KAHN, BRIAN AND CHARLES NEESONS, EDI- TORS. Borders in Cyberspace: Information Policy and the Global Information Infrastructure. Cambridge, . SAJo, ANDRAS AND MONROE E. PRICE, EDI- Mass.: MIT Press, 1997. 374 p. TORS. Rights of Access to the Media. Boston, Mass.: Borders in Cyberspace is a collection of essays pro- Kluwer Law International, 1996. 303 p. duced by the Center for Law and Information Technology at Harvard Law School. The first part Rights of Access to the Media is a collection of es- of the collection consists of six essays which ad- says which examine the theoretical and practical dress the "where" of cyberspace and the legal is- aspects of media access in the United States and Europe. Part I contains essays by Monroe Price sues which arise because of its lack of borders: ju- risdiction, conflict of laws, cultural sovereignty, and Jean Cohen which address the dominant models of access theory. -

Longines-Wittnauer with Eric Johnston

Video Transcript for Archival Research Catalog (ARC) Identifier 95873 Longines-Wittnauer with Eric Johnston Announcer: It’s time for the Longines Chronoscope, a television journal of the important issues of the hour. Brought to you every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. A presentation of the Longines-Wittnauer Watch Company, maker of Longines, the world’s most honored watch, and Wittnauer, distinguished companion to the world honored Longines. Frank Knight: Good evening, this is Frank Knight. May I introduce our coeditors for this edition of the Longines Chronoscope: from the CBS television news staff, Larry Lesueur and Charles Collingwood. Our distinguished guest for this evening is Eric Johnston, Special Emissary of the president to the Near East. Larry Lesueur: Mr. Johnston you’ve done so much work of national importance in the last ten years under three administrations, I guess. I’ve probably covered more of your press conferences than almost anyone else. Now you’ve just returned from the Middle East where you were the Special Emissary of the president. Can you tell us exactly what your mission was there? Eric Johnston: Yes. I went out to the Near East to present a program for the development of the Jordan Valley before the program was presented to the United Nations and perhaps summarily dismissed by the nations involved. The development of the Jordan Valley calls for the irrigation of 240,000 additional acres of land in this area for the development of 65,000 additional horsepower of electric energy. Under this program, the four nations involved in which the Jordan, which comprises the Jordan watershed, would agree upon the division of the waters of the Jordan. -

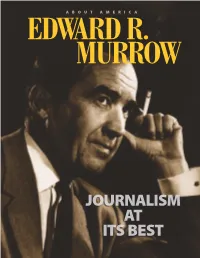

Edward R. Murrow

ABOUT AMERICA EDWARD R. MURROW JOURNALISM AT ITS BEST TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward R. Murrow: A Life.............................................................1 Freedom’s Watchdog: The Press in the U.S.....................................4 Murrow: Founder of American Broadcast Journalism....................7 Harnessing “New” Media for Quality Reporting .........................10 “See It Now”: Murrow vs. McCarthy ...........................................13 Murrow’s Legacy ..........................................................................16 Bibliography..................................................................................17 Photo Credits: University of Maryland; right, Digital Front cover: © CBS News Archive Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Page 1: CBS, Inc., AP/WWP. 12: Joe Barrentine, AP/WWP. 2: top left & right, Digital Collections and Archives, 13: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University; bottom, AP/WWP. Tufts University. 4: Louis Lanzano, AP/WWP. 14: top, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 5 : left, North Wind Picture Archives; bottom, AP/WWP. right, Tim Roske, AP/WWP. 7: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Executive Editor: George Clack 8: top left, U.S. Information Agency, AP/WWP; Managing Editor: Mildred Solá Neely right, AP/WWP; bottom left, Digital Collections Art Director/Design: Min-Chih Yao and Archives, Tufts University. Contributing editors: Chris Larson, 10: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts Chandley McDonald University. Photo Research: Ann Monroe Jacobs 11: left, Library of American Broadcasting, Reference Specialist: Anita N. Green 1 EDWARD R. MURROW: A LIFE By MARK BETKA n a cool September evening somewhere Oin America in 1940, a family gathers around a vacuum- tube radio. As someone adjusts the tuning knob, a distinct and serious voice cuts through the airwaves: “This … is London.” And so begins a riveting first- hand account of the infamous “London Blitz,” the wholesale bombing of that city by the German air force in World War II. -

Edward R. Murrow

Edward R. Murrow Edward Roscoe Murrow (April 25, 1908 – April 27, 1965), born Egbert Roscoe Murrow,[1] was an American broadcast journalist and war correspondent. He first gained Edward R. Murrow prominence during World War II with a series of live radio broadcasts from Europe for the news division of CBS. During the war he recruited and worked closely with a team of war correspondents who came to be known as the Murrow Boys. A pioneer of radio and television news broadcasting, Murrow produced a series of reports on his television program See It Now which helped lead to the censure of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Fellow journalists Eric Sevareid, Ed Bliss, Bill Downs, Dan Rather, and Alexander Kendrick consider Murrow one of journalism's greatest figures, noting his honesty and integrity in delivering the news. Contents Early life Career at CBS Radio Murrow in 1961 World War II Born Egbert Postwar broadcasting career Radio Roscoe Television and films Murrow Criticism of McCarthyism April 25, Later television career Fall from favor 1908 Summary of television work Guilford United States Information Agency (USIA) Director County, North Death Carolina, Honors U.S. Legacy Works Died April 27, Filmography 1965 Books (aged 57) References Pawling, New External links and references Biographies and articles York, U.S. Programs Resting Glen Arden place Farm Early life 41°34′15.7″N 73°36′33.6″W Murrow was born Egbert Roscoe Murrow at Polecat Creek, near Greensboro,[2] in Guilford County, North Carolina, the son of Roscoe Conklin Murrow and Ethel F. (née Lamb) Alma mater Washington [3] Murrow. -

Combatting Fake News

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Southern Methodist University Science and Technology Law Review Volume 20 | Number 2 Article 17 2017 Combatting Fake News: Alternatives to Limiting Social Media Misinformation and Rehabilitating Quality Journalism Dallas Flick Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/scitech Part of the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Dallas Flick, Combatting Fake News: Alternatives to Limiting Social Media Misinformation and Rehabilitating Quality Journalism, 20 SMU Sci. & Tech. L. Rev. 375 (2017) https://scholar.smu.edu/scitech/vol20/iss2/17 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Science and Technology Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. Combatting Fake News: Alternatives to Limiting Social Media Misinformation and Rehabilitating Quality Journalism Dallas Flick* I. INTRODUCTION The continued expansion and development of the Internet has generated a malicious side effect: social media intermediaries such as Facebook and Google permit the dispersion of third-party generated fake news and misin- formation. While the term “fake news” tends to shift in definition, it most frequently denotes blatantly false information posted on the Internet intended to sway opinion.1 The social and political implications for -

The Book Thief

Ryde Library Service Community Book Club Collection Becoming By Michelle Obama First published in 2018 Genre & subject Biography Michelle Obama President’s spouses Synopsis An intimate, powerful, and inspiring memoir by the former First Lady of the United States In a life filled with meaning and accomplishment, Michelle Obama has emerged as one of the most iconic and compelling women of our era. As First Lady of the United States of America- the first African-American to serve in that role-she helped create the most welcoming and inclusive White House in history, while also establishing herself as a powerful advocate for women and girls in the U.S. and around the world, dramatically changing the ways that families pursue healthier and more active lives, and standing with her husband as he led America through some of its most harrowing moments. Along the way, she showed us a few dance moves, crushed Carpool Karaoke, and raised two down-to-earth daughters under an unforgiving media glare. In her memoir, a work of deep reflection and mesmerizing storytelling, Michelle Obama invites readers into her world, chronicling the experiences that have shaped her-from her childhood on the South Side of Chicago to her years as an executive balancing the demands of motherhood and work, to her time spent at the world's most famous address. With unerring honesty and lively wit, she describes her triumphs and her disappointments, both public and private, telling her full story as she has lived it-in her own words and on her own terms. Warm, wise, and revelatory, Becoming is the deeply personal reckoning of a woman of soul and substance who has steadily defied expectations-and whose story inspires us to do the same. -

JWHAU Eo Iiattrijw Tfr Leuf Ntng Lipralji AUSTRIA BACKS ITALY ON

9 V." Dlanrlrratn lEvm ing lirraUt TOTSDAT,. AU GU ST 20, 1988L y ATBBAO B B AH .T CSBOIJUkTlOM ter tlM Moitli of July, IMO t h e w e a t h e r Mr. and Mrs. Jacob Demko, of flames. Before the cloth could be Pero were undecided today - about Forecast o l 0. S. Westber Bmuoii. Summer street, have as their guests pulled down approximately four and running again for the office, al Bartfor4i for the week their nieces. Misses HLLED TOBACCO a half acres of cloth and tobacco had BOWERS, WELIAMS, though It was expected that Mr. Rose and Margaret Berg, and their been destroyed. Tireless work by Pero would be a candidate. 5 , 4 6 8 Member o< tfco Audit Showers this sftemoon sod to- Mr». Charles Ogren of Cooper Hill nephews, John, Edwin and Albert the firemen prevented other build Bowers has served on the board olghC Thursdsy partly cloudy; not Street la spending ten days at Berg from Northampton, Pa. SHED IS BURNED ings on the plantation from falling JENSEN CANDMTES four years, two of which he was Bureau of Orenlations iiattrijw tfr lEuf ntng lipralJi much change in temperature. lu te 's Island, as the guest of Mrs. prey to the flames. secretary. Williams, with Bowers, Harry Linden. Mystic Review, Woman’s Benefit In addition to the tobacco stored was first put into ofifice wrltb the or association, will meet tonight at S in the shed, there were also 250,000 ganized backing of the then newly YOL. L IV , NO. 275. -

Famous Journalist Research Project

Famous Journalist Research Project Name:____________________________ The Assignment: You will research a famous journalist and present to the class your findings. You will introduce the journalist, describe his/her major accomplishments, why he/she is famous, how he/she got his/her start in journalism, pertinent personal information, and be able answer any questions from the journalism class. You should make yourself an "expert" on this person. You should know more about the person than you actually present. You will need to gather your information from a wide variety of sources: Internet, TV, magazines, newspapers, etc. You must include a list of all sources you consult. For modern day journalists, you MUST read/watch something they have done. (ie. If you were presenting on Barbara Walters, then you must actually watch at least one interview/story she has done, or a portion of one, if an entire story isn't available. If you choose a writer, then you must read at least ONE article written by that person.) Source Ideas: Biography.com, ABC, CBS, NBC, FOX, CNN or any news websites. NO WIKIPEDIA! The Presentation: You may be as creative as you wish to be. You may use note cards or you may memorize your presentation. You must have at least ONE visual!! Any visual must include information as well as be creative. Some possibilities include dressing as the character (if they have a distinctive way of dressing) & performing in first person (imitating the journalist), creating a video, PowerPoint or make a poster of the journalist’s life, a photo album, a smore, or something else! The main idea: Be creative as well as informative. -

War: How Britain, Germany and the USA Used Jazz As Propaganda in World War II

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Studdert, Will (2014) Music Goes to War: How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/44008/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Music Goes to War How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II Will Studdert Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Kent 2014 Word count (including footnotes): 96,707 255 pages Abstract The thesis will demonstrate that the various uses of jazz music as propaganda in World War II were determined by an evolving relationship between Axis and Allied policies and projects. -

Blurring Fiction with Reality: American Television and Consumerism in the 1950S

Blurring fiction with reality: American television and consumerism in the 1950s On the evening of 15 October 1958, veteran correspondent Edward R. Murrow stood at the podium and looked out over the attendees of the annual Radio Television Digital News Association gala. He waited until complete silence descended, and then launched into a speech that he had written and typed himself, to be sure that no one could possibly have had any forewarning about its contents. What followed was a scathing attack on the state of the radio and television industries, all the more meaningful coming from a man who was widely acknowledged as not only the architect of broadcast journalism but also a staunch champion of ethics and integrity in broadcasting.1 This was the correspondent who had stood on the rooftops of London with bombs exploding in the background to bring Americans news of the Blitz, whose voice was familiar to millions of Americans. This was the man who had publicly eviscerated the redbaiting Senator Joseph McCarthy, helping to put an end to a shameful period in America’s history (see e.g. Mirkinson, 2014, Sperber, 1986). And it became apparent that evening that this was also a man bitterly disappointed with the “incompatible combination of show business, advertising and news” that the broadcasting industry had become: Our history will be what we make it. And if there are any historians about fifty or a hundred years from now, and there should be preserved the kinescopes for one week of all three networks, they will there find recorded in black and white, or color, evidence of decadence, escapism and insulation from the realities of the world in which we live.