Uvic Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gay Pride on Stolen Land: Homonationalism, Queer Asylum

Gay Pride on Stolen Land: Homonationalism, Queer Asylum and Indigenous Sovereignty at the Vancouver Winter Olympics Paper submitted for publication in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies August 2012 Abstract In this paper we examine intersections between homonationalism, sport, gay imperialism and white settler colonialism. The 2010 Winter Olympics, held in Vancouver, Canada, produced new articulations between sporting homonationalism, indigenous peoples and immigration policy. For the first time at an Olympic/Paralympic Games, three Pride Houses showcased LGBT athletes and provided support services for LBGT athletes and spectators. Supporting claims for asylum by queers featured prominently in these support services. However, the Olympic events were held on unceded territories of four First Nations, centered in Vancouver which is a settler colonial city. Thus, we examine how this new form of ‘sporting homonationalism’ emerged upon unceded, or stolen, indigenous land of British Columbia in Canada. Specifically, we argue that this new sporting homonationalism was founded upon white settler colonialism and imperialism—two distinct logics of white supremacy (Smith, 2006).1 Smith explained how white supremacy often functions through contradictory, yet interrelated, logics. We argue that distinct logics of white settler colonialism and imperialism shaped the emergence of the Olympic Pride Houses. On the one hand, the Pride Houses showed no solidarity with the major indigenous protest ‘No Olympics On Stolen Land.’ This absence of solidarity between the Pride Houses and the ‘No Olympics On Stolen Land’ protests reveals how thoroughly winter sports – whether elite or gay events — depend on the logics, and material practices, of white settler colonialism. We analyze how 2 the Pride Houses relied on colonial narratives about ’Aboriginal Participation’ in the Olympics and settler notions of ‘land ownership’. -

A History of Mexican Workers on the Oxnard Plain 1930-1980

LABOR, MIGRATION, AND ACTIVISM: A HISTORY OF MEXICAN WORKERS ON THE OXNARD PLAIN 1930-1980 By Louie Herrera Moreno III A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chicano/Latino Studies 2012 ABSTRACT LABOR, MIGRATION, AND ACTIVISM: A HISTORY OF MEXICAN WORKERS ON THE OXNARD PLAIN 1930-1980 By Louie Herrera Moreno III First and foremost, this dissertation focuses on the relationship between labor and migration in the development of the City of Oxnard and La Colonia neighborhood. Labor and migration on the Oxnard Plain have played an important part in shaping and constructing the Mexican working-class community and its relationship to the power structure of the city and the agri-business interests of Ventura County. This migration led to many conflicts between Mexicans and Whites. I focus on those conflicts and activism between 1930 and 1980. Secondly, this dissertation expands on early research conducted on Mexicans in Ventura County. The Oxnard Plain has been a key location of struggles for equality and justice. In those struggles, Mexican residents of Oxnard, the majority being working- class have played a key role in demanding better work conditions, housing, and wages. This dissertation continues the research of Tomas Almaguer, Frank P. Barajas, and Martha Menchaca, who focused on class, race, work, leisure, and conflict in Ventura County. Thirdly, this dissertation is connected to a broader history of Mexican workers in California. This dissertation is influenced by important research conducted by Carey McWilliams, Gilbert Gonzalez, Vicki Ruiz, and other historians on the relationship between labor, migration, and activism among the Mexican working-class community in Southern California. -

Gay and Transgender Communities - Sexual And

HOMO-SEXILE: GAY AND TRANSGENDER COMMUNITIES - SEXUAL AND NATIONAL IDENTITIES IN LATIN AMERICAN FICTION AND FILM by Miguel Moss Marrero APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: __________________________________________ Michael Wilson, Chair __________________________________________ Adrienne L. McLean __________________________________________ Robert Nelsen __________________________________________ Rainer Schulte __________________________________________ Teresa M. Towner Copyright 2018 Miguel Moss Marrero All Rights Reserved -For my father who inspired me to be compassionate, unbiased, and to aspire towards a life full of greatness. HOMO-SEXILE: GAY AND TRANSGENDER COMMUNITIES - SEXUAL AND NATIONAL IDENTITIES IN LATIN AMERICAN FICTION AND FILM by MIGUEL MOSS MARRERO BA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS August 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Latin American transgender women and gay men are part of my family. This dissertation is dedicated to them. It would have not been possible without their stories. I want to give my gratitude to my mother, who set an example by completing her doctoral degree with three exuberant boys and a full-time job in mental health. I also want to dedicate this to my father, who encouraged me to accomplish my goals and taught me that nothing is too great to achieve. I want to thank my siblings who have shown support throughout my doctoral degree. I also want to thank my husband, Michael Saginaw, for his patience while I spent many hours in solitude while writing my dissertation. Without all of their support, this chapter of my life would have been meaningless. -

Gail Gallagher

Art, Activism and the Creation of Awareness of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG); Walking With Our Sisters, REDress Project by Gail Gallagher A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Native Studies University of Alberta © Gail Gallagher, 2020 ABSTRACT Artistic expression can be used as a tool to promote activism, to educate and to provide healing opportunities for the families of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG). Indigenous activism has played a significant role in raising awareness of the MMIWG issue in Canada, through the uniting of various Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. The role that the Walking With Our Sisters (WWOS) initiative and the REDress project plays in bringing these communities together, to reduce the sexual exploitation and marginalization of Indigenous women, will be examined. These two commemorative projects bring an awareness of how Indigenous peoples interact with space in political and cultural ways, and which mainstream society erases. This thesis will demonstrate that through the process to bring people together, there has been education of the MMIWG issue, with more awareness developed with regards to other Indigenous issues within non-Indigenous communities. Furthermore, this paper will show that in communities which have united in their experience with grief and injustice, healing has begun for the Indigenous individuals, families and communities affected. Gallagher ii DEDICATION ka-kiskisiyahk iskwêwak êkwa iskwêsisak kâ-kî-wanihâyahkik. ᑲᑭᐢ ᑭᓯ ᔭ ᐠ ᐃᐢ ᑫᐧ ᐊᐧ ᕽ ᐁᑲᐧ ᐃᐢ ᑫᐧ ᓯ ᓴ ᐠ ᑳᑮᐊᐧ ᓂᐦ ᐋᔭᐦ ᑭᐠ We remember the women and girls we have lost.1 1 Cree Literacy Network. -

Exploring Connections Between Efforts to Restrict Same-Sex Marriage and Surging Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2014 Exploring Connections Between Efforts to Restrict Same-Sex Marriage and Surging Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage Rights: Could Efforts to Restrict Gay Rights Help to Explain Increases in Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage? Samuel Everett Christian Dunlop Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dunlop, Samuel Everett Christian, "Exploring Connections Between Efforts to Restrict Same-Sex Marriage and Surging Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage Rights: Could Efforts to Restrict Gay Rights Help to Explain Increases in Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage?" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1785. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1784 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Exploring Connections Between Efforts to Restrict Same-Sex Marriage and Surging Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage Rights: Could Efforts to Restrict Gay Rights Help to Explain Increases in Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage? by Samuel Everett Christian Dunlop A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Thesis Committee: Kim Williams, Chair Richard Clucas David Kinsella Portland State University 2014 Abstract Scholarly research on the subject of the swift pace of change in support for same-sex marriage has evolved significantly over the last ten years. -

To Oral History

100 E. Main St. [email protected] Ventura, CA 93001 (805) 653-0323 x 320 QUARTERLY JOURNAL SUBJECT INDEX About the Index The index to Quarterly subjects represents journals published from 1955 to 2000. Fully capitalized access terms are from Library of Congress Subject Headings. For further information, contact the Librarian. Subject to availability, some back issues of the Quarterly may be ordered by contacting the Museum Store: 805-653-0323 x 316. A AB 218 (Assembly Bill 218), 17/3:1-29, 21 ill.; 30/4:8 AB 442 (Assembly Bill 442), 17/1:2-15 Abadie, (Señor) Domingo, 1/4:3, 8n3; 17/2:ABA Abadie, William, 17/2:ABA Abbott, Perry, 8/2:23 Abella, (Fray) Ramon, 22/2:7 Ablett, Charles E., 10/3:4; 25/1:5 Absco see RAILROADS, Stations Abplanalp, Edward "Ed," 4/2:17; 23/4:49 ill. Abraham, J., 23/4:13 Abu, 10/1:21-23, 24; 26/2:21 Adams, (rented from Juan Camarillo, 1911), 14/1:48 Adams, (Dr.), 4/3:17, 19 Adams, Alpha, 4/1:12, 13 ph. Adams, Asa, 21/3:49; 21/4:2 map Adams, (Mrs.) Asa (Siren), 21/3:49 Adams Canyon, 1/3:16, 5/3:11, 18-20; 17/2:ADA Adams, Eber, 21/3:49 Adams, (Mrs.) Eber (Freelove), 21/3:49 Adams, George F., 9/4:13, 14 Adams, J. H., 4/3:9, 11 Adams, Joachim, 26/1:13 Adams, (Mrs.) Mable Langevin, 14/1:1, 4 ph., 5 Adams, Olen, 29/3:25 Adams, W. G., 22/3:24 Adams, (Mrs.) W. -

Gender and Sexuality Diverse Student Inclusive Practices: Challenges Facing Educators

Journal of Initial Teacher Inquiry (2016). Volume 2 Gender and Sexuality Diverse Student Inclusive Practices: Challenges Facing Educators Catherine Edmunds Te Rāngai Ako me te Hauora - College of Education, Health and Human Development, University of Canterbury, New Zealand Abstract Inclusivity is at the heart of education in New Zealand and is founded on the key principle that every student deserves to feel like they belong in the school environment. One important aspect of inclusion is how Gender and Sexuality Diverse (GSD) students are being supported in educational settings. This critical literature review identified three key challenges facing educators that prevent GSD students from being fully included at school. Teachers require professional development in order to discuss GSD topics, bullying and harassment of GSD individuals are dealt with on an as-needs basis rather than address underlying issues, and a pervasive culture of heteronormativity both within educational environments and New Zealand society all contribute to GSD students feeling excluded from their learning environments. A clear recommendation drawn from the literature examined is that the best way to instigate change is to use schools for their fundamental purpose: learning. Schools need to learn strategies to make GSD students feel safe, teachers need to learn how to integrate GSD topics into their curriculum and address GSD issues within the school, and students need to learn how to understand the gender and sexuality diverse environments they are growing up in. Keywords: Gender, Sexuality, Diverse, Pre-Service Teacher, Education, New Zealand, Heteronormativity, Harassment Journal of Initial Teacher Inquiry by University of Canterbury is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. -

ABSTRACT TAYLOR, JAMI KATHLEEN. the Adoption of Gender Identity Inclusive Legislation in the American States. (Under the Direct

ABSTRACT TAYLOR, JAMI KATHLEEN. The Adoption of Gender Identity Inclusive Legislation in the American States. (Under the direction of Andrew J. Taylor.) This research addresses an issue little studied in the public administration and political science literature, public policy affecting the transgender community. Policy domains addressed in the first chapter include vital records laws, health care, marriage, education, hate crimes and employment discrimination. As of 2007, twelve states statutorily protect transgender people from employment discrimination while ten include transgender persons under hate crimes laws. An exploratory cross sectional approach using logistic regression found that public attitudes largely predict which states adopt hate crimes and/or employment discrimination laws. Also relevant are state court decisions and the percentage of Democrats within the legislature. Based on the logistic regression’s classification results, four states were selected for case study analysis: North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Massachusetts. The case studies found that legislators are often reluctant to support transgender issues due to the community’s small size and lack of resources. Additionally, transgender identity’s association with gay rights is both a blessing and curse. In conservative districts, particularly those with large Evangelical communities, there is strong resistance to LGBT rights. However, in more tolerant areas, the association with gay rights advocacy groups can foster transgender inclusion in statutes. Legislators perceive more leeway to support LGBT rights. However, gay activists sometimes remove transgender inclusion for political expediency. As such, the policy core of many LGBT interest groups appears to be gay rights while transgender concerns are secondary items. In the policy domains studied, transgender rights are an extension of gay rights. -

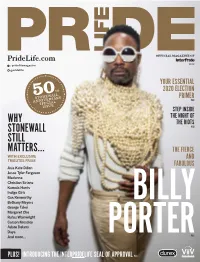

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

WATERGATE: WHY NIXON FEARS DEAN's ~-=TESTIM -Page 13

JUNE 29, 1973 25 CENTS VOLUME 37 /NUMBER 25 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE WATERGATE: WHY NIXON FEARS DEAN'S ~-=TESTIM -page 13 Millions of, people think Nixon would fail lie detector test, but this David Levine drawing was re;ected by the New York Times and the Washington Post as 'too hot to handle: It was first published by Rights, magazine of the Nationa1 1Emergency Civil Liberties Committee. For watergate news, see pages 13-16. Brezhnev-Nixon deals= no step ·toward pea~~ In Brief NEW DEATH SENTENCES IN IRAN: A military tri largely on testimony given by a well-known professional bunal in Teheran condemned six men 'to death on June witness for the L.A. police department in drug cases in 10 and one woman, Simeen Nahavandi, to a 10-year volving Blacks. Seven other witnesses testified that Smith term in solitary confinement. The verdict has been ap was nowhere near the place where he allegedly sold the pealed to a military review board, which ordinarily gives drugs on that day. There were no Blacks on the jury. speedy approval to such sentences. (For more information Smith, whose sentencing is scheduled for July 10, faces on the repression in Iran, see the World Outlook section.) five years to life under California's indeterminate sen tencing law. The Mongo Smith Defense Committee is THIS YSA LEADER CONDEMNS PERSECUTION OF IRAN looking into appealing his conviction. IAN STUDENTS: The recent indictment of six Iranian students accused of assaulting an Iranian consular official WEEK'S CHICANOS WIN FIGHT FOR A NEW SCHOOL: Chi in San Francisco March 26 has been strongly condemned canos in Chicago's Pilsen community won a significant by Andrew Pulley, national secretary of the Young So MILITANT victory when the board of education agreed recently to cialist Alliance. -

Thèse Et Mémoire

Université de Montréal Survivance 101 : Community ou l’art de traverser la mutation du paysage télévisuel contemporain Par Frédérique Khazoom Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques, Université de Montréal, Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de Maîtrise ès arts en Maîtrise en cinéma, option Cheminement international Décembre 2019 © Frédérique Khazoom, 2019 Université de Montréal Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Ce mémoire intitulé Survivance 101 : Community ou l’art de traverser la mutation du paysage télévisuel contemporain Présenté par Frédérique Khazoom A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes Zaira Zarza Président-rapporteur Marta Boni Directeur de recherche Stéfany Boisvert Membre du jury Résumé Lors des années 2000, le paysage télévisuel américain a été profondément bouleversé par l’arrivée d’Internet. Que ce soit dans sa production, sa création ou sa réception, l’évolution rapide des technologies numériques et l’apparition des nouveaux médias ont contraint l’industrie télévisuelle à changer, parfois contre son gré. C’est le cas de la chaîne généraliste américaine NBC, pour qui cette période de transition a été particulièrement difficile à traverser. Au cœur de ce moment charnière dans l’histoire de la télévision aux États-Unis, la sitcom Community (NBC, 2009- 2014; Yahoo!Screen, 2015) incarne et témoigne bien de différentes transformations amenées par cette convergence entre Internet et la télévision et des conséquences de cette dernière dans l’industrie télévisuelle. L’observation du parcours tumultueux de la comédie de situation ayant débuté sur les ondes de NBC dans le cadre de sa programmation Must-See TV, entre 2009 et 2014, avant de se terminer sur le service par contournement Yahoo! Screen, en 2015, permet de constater que Community est un objet télévisuel qui a constamment cherché à s’adapter à un média en pleine mutation. -

Programme De Développement

PROGRAMME DE DÉVELOPPEMENT/DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM Liste des festivals admissibles pour le volet autochtone et le volet destiné aux Noirs et aux Personnes de couleur/ List of Qualifying Festivals for the Indigenous Stream and the Stream for Black and People of Colour • AFI Docs Film Festival, • AFI FEST - American Film Institute (Los Angeles) • African Movie Festival in Manitoba • Afro Prairie Film Festival • Alianait Arts Festival • American Black Film Festival (Miami) • American Indian Film Festival • Annecy International Animated Film Festival - Festival International du Film d’Animation Annecy • Arica Nativa International Rural + Indigenous Film Festival • Asinabka Film & Media Arts Festival • Atlanta Film Festival • Available Light Film Festival • Banff Mountain Film Festival • Banff World Media Festival • Barrie Film Festival • Beijing International Film Festival • Berlin International Film Festival • BFI London Film Festival • Big Sky Documentary Film Festival • Bleak Midwinter Film Festival • Blood in the Snow Canadian Film Festival • Bloody Horror International Film Festival • Boomerang Festival • Brussels International Fantastic Film Festival • Bucheon (previously Puchon) International Fantastic Film Festival (BiFan) – • Buenos Aires Festival Internacional de Cine Independiente - BAFICI - Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema • BUFF Malmö Film Festival • Busan International Film Festival Eligible • Calgary Independent Film Festival • Calgary International Film Festival • Calgary Underground Film Festival • California