A History of Mexican Workers on the Oxnard Plain 1930-1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libraries Connected by the End of Year

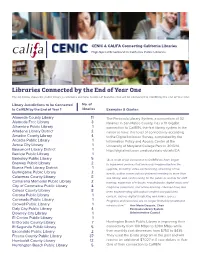

CENIC & CALIFA Connecting California Libraries High-Speed Broadband in California Public Libraries Libraries Connected by the End of Year One The list below shows the public library jurisdictions and total number of branches that will be connected to CalREN by the end of Year One. Library Jurisdictions to be Connected No. of to CalREN by the End of Year 1 libraries Examples & Quotes: Alameda County Library 11 The Peninsula Library System, a consortium of 32 Alameda Free Library 3 libraries in San Mateo County, has a 10 Gigabit Alhambra Public Library 1 connection to CalREN, the first library system in the Altadena Library District 2 nation to have this level of connectivity according Amador County Library 4 to the Digital Inclusion Survey, completed by the Arcadia Public Library 1 Information Policy and Access Center at the Azusa City Library 1 University of Maryland College Park in 2013/14, Beaumont Library District 1 http://digitalinclusion.umd.edu/state-details/CA. Benicia Public Library 1 Berkeley Public Library 5 “As a result of our connection to CalREN we have begun Brawley Public Library 2 to implement services that were only imagined before the Buena Park Library District 1 upgrade, including: video-conferencing; streaming of live Burlingame Public Library 2 events; author conversations delivered remotely to more than Calaveras County Library 8 one library; web-conferencing for the public as well as for staff Camarena Memorial Public Library 2 training; expansion of e-books, e-audiobooks, digital music and City of Commerce Public Library 4 magazine collections, and online learning. Libraries have also Colusa County Library 8 been experimenting with patron-created and published Corona Public Library 1 content, such as digital storytelling and maker spaces. -

BIOGRAPHIES Fiona Ma, California State Treasurer

BIOGRAPHIES Fiona Ma, California State Treasurer Fiona Ma is California’s 34th State Treasurer. She was elected on November 6, 2018 with more votes (7,825,587) than any other candidate for treasurer in the state's history. She is the first woman of color and the first woman Certified Public Accountant (CPA) elected to the position. The State Treasurer’s Office was created in the California Constitution in 1849. It provides financing for schools, roads, housing, recycling and waste management, hospitals, public facilities, and other crucial infrastructure projects that better the lives of residents. California is the world’s fifth-largest economy and Treasurer Ma is the state’s primary banker. Her office processes more than $2 trillion in payments within a typical year and provides transparency and oversight for an investment portfolio of more than $90 billion, approximately $20 billion of which are local government funds. She also is responsible for $85 billion in outstanding general obligation and lease revenue bonds of the state. The Treasurer works closely with the State Legislature to ensure that its members know the state’s financial condition as they consider new legislation. She gives her own recommendations for the annual budget. Treasurer Ma was a member of the State Assembly from 2006-2012, serving as Speaker pro Tempore from 2010 to 2012. She built a reputation as a solution-oriented public servant and was adept at building unlikely coalitions to overcome California's most complex problems. Prior to serving as Speaker pro Tempore, she was Assembly Majority Whip and built coalitions during a state budget crisis to pass groundbreaking legislation that protected public education and the environment while also expanding access to health care. -

Profiletemplate 9-8-11.Xlsm

Understanding California's Demographic Shifts Table of Contents 38% 1.5 0.75 0 0.75 1.5 Adele M. Hayutin, PhD Kimberly Kowren Gary Reynolds Camellia Rodriguez-SackByrne Amy Teller Prepared for the California State Library September 2011 Stanford Center on Longevity http://longevity.stanford.edu This project was supported in whole by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act, administered in California by the State Librarian. The opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services or the California State Library, and no official endorsement by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services or the California State Library should be inferred. Understanding California's Demographic Shifts Table of Contents VOLUME 1 Introduction California Demographic Overview Drawing Implications from the Demographics Demographic Profiles for Library Jurisdictions, A‐M A Colusa County Free Library Inglewood Public Library A. K. Smiley Public Library Contra Costa County Library Inyo County Free Library Alameda County Library Corona Public Library Irwindale Public Library Alameda Free Library Coronado Public Library K Alhambra Civic Center Library County of Los Angeles Public Kern County Library Alpine County Library/Archives Library Kings County Library Altadena Library District Covina Public Library Amador County Library Crowell Public Library L Anaheim Public Library Lake County Library D Arcadia Public Library -

Appendix B Cultural Resources Assessment Study

Appendix B Cultural Resources Assessment Study 280-330 Skyway Drive Development Project Cultural Resources Assessment Report prepared for City of Camarillo Department of Community Development 601 Carmen Drive Camarillo, California 93010 John Novi, Senior Planner prepared by Rincon Consultants, Inc. 209 East Victoria Street Santa Barbara, California 93101 June 2021 Please cite this report as follows: Williams, James, Alexandra Madsen, Steven Treffers, and Shannon Carmack 2021. 280-330 Skyway Drive Development Project Cultural Resources Assessment Report. Rincon Consultants, Inc., Project No. 21-11061. City of Camarillo Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................1 Purpose and Scope .........................................................................................................................1 Dates of Investigation .....................................................................................................................1 Summary of Findings ......................................................................................................................1 CUL-1 Unanticipated Discovery of Cultural Resources .......................................................2 Unanticipated Discovery of Human Remains .....................................................................2 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................3 -

To Oral History

100 E. Main St. [email protected] Ventura, CA 93001 (805) 653-0323 x 320 QUARTERLY JOURNAL SUBJECT INDEX About the Index The index to Quarterly subjects represents journals published from 1955 to 2000. Fully capitalized access terms are from Library of Congress Subject Headings. For further information, contact the Librarian. Subject to availability, some back issues of the Quarterly may be ordered by contacting the Museum Store: 805-653-0323 x 316. A AB 218 (Assembly Bill 218), 17/3:1-29, 21 ill.; 30/4:8 AB 442 (Assembly Bill 442), 17/1:2-15 Abadie, (Señor) Domingo, 1/4:3, 8n3; 17/2:ABA Abadie, William, 17/2:ABA Abbott, Perry, 8/2:23 Abella, (Fray) Ramon, 22/2:7 Ablett, Charles E., 10/3:4; 25/1:5 Absco see RAILROADS, Stations Abplanalp, Edward "Ed," 4/2:17; 23/4:49 ill. Abraham, J., 23/4:13 Abu, 10/1:21-23, 24; 26/2:21 Adams, (rented from Juan Camarillo, 1911), 14/1:48 Adams, (Dr.), 4/3:17, 19 Adams, Alpha, 4/1:12, 13 ph. Adams, Asa, 21/3:49; 21/4:2 map Adams, (Mrs.) Asa (Siren), 21/3:49 Adams Canyon, 1/3:16, 5/3:11, 18-20; 17/2:ADA Adams, Eber, 21/3:49 Adams, (Mrs.) Eber (Freelove), 21/3:49 Adams, George F., 9/4:13, 14 Adams, J. H., 4/3:9, 11 Adams, Joachim, 26/1:13 Adams, (Mrs.) Mable Langevin, 14/1:1, 4 ph., 5 Adams, Olen, 29/3:25 Adams, W. G., 22/3:24 Adams, (Mrs.) W. -

The Formation of Subjectivity in Mexican American Life Narratives

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-9-2011 Ghostly I(s)/Eyes: The orF mation of Subjectivity in Mexican American Life Narratives Patricia Marie Perea Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Recommended Citation Perea, Patricia Marie. "Ghostly I(s)/Eyes: The orF mation of Subjectivity in Mexican American Life Narratives." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/34 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i ii © 2010, Patricia Marie Perea iii DEDICATION por mi familia The smell of cedar can break the feed yard. Some days I smell nothing until she opens her chest. Her polished nails click against tarnished metal Cleek! Then the creek of the hinge and the memories open, naked and total. There. A satin ribbon curled around a ringlet of baby fine hair. And there. A red and white tassel, its threads thick and tangled. Look here. She picks up a newspaper clipping, irons out the wrinkles between her hands. I kept this. We remember this. It is ours. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Until quite recently, I did not know how many years ago this dissertation began. It did not begin with my first day in the Ph.D. program at the University of New Mexico in 2000. Nor did it begin with my first day as a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin in 1997. -

Gender and Sexuality Diverse Student Inclusive Practices: Challenges Facing Educators

Journal of Initial Teacher Inquiry (2016). Volume 2 Gender and Sexuality Diverse Student Inclusive Practices: Challenges Facing Educators Catherine Edmunds Te Rāngai Ako me te Hauora - College of Education, Health and Human Development, University of Canterbury, New Zealand Abstract Inclusivity is at the heart of education in New Zealand and is founded on the key principle that every student deserves to feel like they belong in the school environment. One important aspect of inclusion is how Gender and Sexuality Diverse (GSD) students are being supported in educational settings. This critical literature review identified three key challenges facing educators that prevent GSD students from being fully included at school. Teachers require professional development in order to discuss GSD topics, bullying and harassment of GSD individuals are dealt with on an as-needs basis rather than address underlying issues, and a pervasive culture of heteronormativity both within educational environments and New Zealand society all contribute to GSD students feeling excluded from their learning environments. A clear recommendation drawn from the literature examined is that the best way to instigate change is to use schools for their fundamental purpose: learning. Schools need to learn strategies to make GSD students feel safe, teachers need to learn how to integrate GSD topics into their curriculum and address GSD issues within the school, and students need to learn how to understand the gender and sexuality diverse environments they are growing up in. Keywords: Gender, Sexuality, Diverse, Pre-Service Teacher, Education, New Zealand, Heteronormativity, Harassment Journal of Initial Teacher Inquiry by University of Canterbury is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. -

California Library Statistics 2005 ISSN 0741-031X

California Library Statistics 2005 Fiscal year 2003–2004 from Public, Academic, Special and County Law Libraries Library Development Services Bureau Sacramento, 2005 Susan Hildreth, State Librarian of California 5797-1 California Library Statistics 2005 Fiscal year 2003–2004 from Public, Academic, Special and County Law Libraries Library Development Services Bureau Sacramento, 2005 Susan Hildreth, State Librarian of California 5797-1 California Library Statistics 2005 ISSN 0741-031X Questions or Comments: Ira Bray, Editor Library Development Services Bureau California State Library 900 N St STE 500 PO Box 942837, Sacramento CA 94237-0001 Tel. (916) 653-0171 FAX (916) 653-8443 Printed by the California Department of General Services, Office of State Publishing Distributed via the Library Distribution Act 4589-2 Contents Statewide Statistics State Summary of Library Statistics Page 1 Summary of Public Library Statistics Expenditure/Capita 6 Materials Expenditure/Capita 7 Materials Available/Capita 8 Population Served/Staff Member 9 Books/Capita 10 Public Library Statistics 11 Public Library Tables 19 Group 1, over 500,000 population (15 libraries) Group 2, 150,000 to 500,000 population (29 libraries) Group 3, 100,000 to 150,000 population (27 libraries) Group 4, 60,000 to 100,000 population (31 libraries) Group 5, 40,000 to 60,000 population (25 libraries) Group 6, 20,000 to 40,000 population (22 libraries) Group 7, under 20,000 population (30 libraries) Mobile Libraries (61 mobile libraries) Academic Library Statistics Group A, Public, -

Los Angeles Farmers Markets

FOOD Where to find & enjoy GUIDEFIRST EDITION the local foods of Ventura, Santa Barbara, & Northern Los Angeles Counties RESTAURANTS FARMS FARM STANDS CATERERS GRO C ERS C SA S FARMERS MARKETS Community Alliance with Family Farmers www.caff.org Ventura County Certified VENTURA COUNTY CERTIFIED FARMERS’ MARKETS “FRESH FROM THE FIELDS TO YOU!” Four Outdoor Locations for Your Family to Enjoy SUNDAYS WEDNESDAYS SANTA CLARITA MIDTOWN VENTURA 8:30 AM - 12:00 NOON 9:00 AM - 1:00 PM College of the Canyons Pacific View Mall Valencia Boulevard West Parking Lot, South of Sears Parking Lot 8 on Main Street THURSDAYS SATURDAYS THOUSAND OAKS DOWNTOWN VENTURA 2:00 PM TO 6:30 PM 8:30 AM TO 12 NOON The Oaks Shopping Center City Parking Lot East End Parking Lot • Wilbur Rd. Santa Clara & Palm Streets FOR MORE INFORMATION (805) 529-6266 www.vccfarmersmarkets.com This guide is your companion in discovering and enjoying the local foods of Ventura, Santa Barbara, and northern About this Guide Los Angeles Counties. Our region is fortunate to have rich soils, a year-round growing season, and a commitment to protecting our valuable farmlands. These assets are more important than ever in a world of rising energy and food costs, climate change, and growing concerns about food safety and food security. Like other areas on the urban fringe, however, there is enormous pressure to pave over farmland, and our farmers are stretched thin by complex regulations, weather and water uncertainties, labor shortages, and global price competition. Buying locally grown foods won’t solve all our problems, but it’s a great step in the right direction. -

Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Channel Islands National Park, California

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2006/354 Water Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center Natural Resource Program Centerent of the Interior ASSESSMENT OF COASTAL WATER RESOURCES AND WATERSHED CONDITIONS AT CHANNEL ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA Dr. Diana L. Engle The National Park Service Water Resources Division is responsible for providing water resources management policy and guidelines, planning, technical assistance, training, and operational support to units of the National Park System. Program areas include water rights, water resources planning, marine resource management, regulatory guidance and review, hydrology, water quality, watershed management, watershed studies, and aquatic ecology. Technical Reports The National Park Service disseminates the results of biological, physical, and social research through the Natural Resources Technical Report Series. Natural resources inventories and monitoring activities, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences are also disseminated through this series. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service. Copies of this report are available from the following: National Park Service (970) 225-3500 Water Resources Division 1201 Oak Ridge Drive, Suite 250 Fort Collins, CO 80525 National Park Service (303) 969-2130 Technical Information Center Denver Service Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 Cover photos: Top Left: Santa Cruz, Kristen Keteles Top Right: Brown Pelican, NPS photo Bottom Left: Red Abalone, NPS photo Bottom Left: Santa Rosa, Kristen Keteles Bottom Middle: Anacapa, Kristen Keteles Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Channel Islands National Park, California Dr. -

Ventura County Watershed Protection District 2013 Groundwater Section Annual Report

Ventura County Watershed Protection District Water & Environmental Resources Division 2013 Groundwater Section Annual Report Ventura County Watershed Protection District Water & Environmental Resources Division MISSION: “Protect, sustain, and enhance Ventura County watersheds now and into the future for the benefit of all by applying sound science, technology, and policy.” 2013 Groundwater Section Annual Report Cover Photo: Drip irrigation of celery on the Oxnard Plain. 2013 Groundwater Section Annual Report Contents Sections Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Summary of Accomplishments 1 1.2 General County Information 2 1.2.1 Population and Climate 2 1.2.2 Surface Water 4 1.2.3 Groundwater 5 2.0 Duties and Responsibilities 7 2.1 Well Ordinance 7 2.1.1 Permits 7 2.1.2 Inspections 7 2.2 Inventory & Status of Wells 9 3.0 Groundwater Quality 10 3.1 Water Quality Sampling 10 3.2 Current Conditions 11 3.2.1 Oxnard Plain Pressure Basin 14 3.2.1.1 Oxnard Aquifer 15 3.2.1.2 Mugu Aquifer 15 3.2.1.3 Hueneme Aquifer 16 3.2.1.4 Fox Canyon Aquifer 17 3.2.2 Fillmore Basin 19 3.2.3 Santa Paula Basin 21 3.2.4 Piru Basin 23 3.2.5 Pleasant Valley Basin 25 3.2.6 Mound Basin 27 3.2.7 East Las Posas Basin 29 3.2.8 West Las Posas Basin 31 3.2.9 Oxnard Forebay Basin 33 3.2.10 South Las Posas Basin 35 3.2.11 Lower Ventura River Basin 37 2013 Groundwater Section Annual Report Contents Sections (con’t.) Page 3.2.12 Cuyama Valley Basin 39 3.2.13 Simi Valley Basin 41 3.2.14 Thousand Oaks Basin 43 3.2.15 Tapo/Gillibrand Basin 45 3.2.16 Arroyo Santa Rosa -

Destination Facts

Destination Facts LOCATION CLIMATE Set on the California coastline with 7 miles/11 kilometers of Oxnard boasts a moderate Mediterranean (dry subtropical) pristine beaches, Oxnard is located betwixt the stunning climate year-round, in a climate designated the “warm-summer backdrops of the Topatopa Mountains to the north and Mediterranean climate” by the Köppen climate Channel Islands National Park across the Santa Barbara Channel classification system. to the south. The Oxnard plain is surrounded by the Santa Clara River, agricultural land and the Pacific Ocean. Just 60 miles/96 • RAINFALL: Oxnard experiences an annual average rainfall kilometers north of Los Angeles and 38 miles/61 kilometers of 15.64 inches. The wettest months are in the winter, with south of Santa Barbara, Oxnard is located just past Malibu, peak rainfall happening in February and the rainless period beyond Point Mugu and the Santa Monica Mountains, where of the year lasts from April 29 to October 12. You won’t Pacific Coast Highway (PCH) meets Highway 101. find a ski forecast for Oxnard, but can certainly check the Oxnard surf report. SIZE • SUNLIGHT: Oxnard enjoys 276 sunny days per year. The longest day of the year is June 21, with more than 14 hours Ventura County encompasses the cities and communities of of sunlight. Conversely, the shortest day of the year is Camarillo, Fillmore, Moorpark, Ojai, Oxnard, Port Hueneme, December 21, with fewer than 10 hours of sunlight. The Santa Paula, Simi Valley, Thousand Oaks and San Buenaventura latest sunset is at 8:12pm on June 29; the earliest is 4:46pm (Ventura) as well as Channel Islands National Park.