Syrians Under Siege: the Role of Local Councils

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

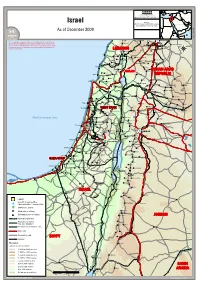

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

Territorial Control Map - Southern Front - 20 Feb 2017 Eldili Southern Fronts (SF) & Islamic Groups (IG)

Territorial Control Map - Southern Front - 20 Feb 2017 Eldili Southern Fronts (SF) & Islamic Groups (IG) Nawa Yarmouk Martyrs Brigade - ISIS Syrian Regime and Allied Militias Saidah Recently Captured by SF/IG Abu Hartin Ain Thakar Izraa Recently Captured by ISIS Buser al Harir Information Unit Information Al Shabrak El Shykh sa´ad Tasil Al Sheikh Maskin Melihit Al Atash Al Bunyan Al Marsous Adawan Garfah Military Operation Room Nafa`ah Israeli occupation Jamlah Ibtta Nahtah - Southern Front Factions, Islamic Opposition & Sahem El Golan Aabdyn HTS Launched (Death over Humiliation) Battle Al Shajarah Jillin Housing Daraa City, & captured Most of Al Manshia Alashaary Mlaiha el Sharqiah Baiyt Irah Jillin Dael El Sourah District & capturing part of the highway that lead Elmah Al Hrak Hayt Mlaihato (Customs el Garbiah Crossing Border), postponing by that Al Qussyr Tafas Khirbet Ghazaleh any Syrian Regime attempts to Re-Open it. Zaizon - First OfficialAl Darah reaction from Jordan Government Muzayrib Al Thaala was closing 90 KM of its borderAl Suwayda with Daraa & Quneitra against everyone, even injured civilians. Tal Shihab El Karak Western Ghariyah Al Yadudah Eastern Ghariyah - Military Operations Center (MOC) reaction was Athman putting pressure on Southern Front Factions to stop the battleUmm Wald or at least participating in it. Yarmouk Martyrs Brigade Elnaymah Al Musayfrah Daraa Saida Jbib Attacks on Opposition Kiheel Al Manshia - 20 Feb 2017 (Yarmouk Martyrs Brigade - ISIS) El SahoahLunched a new battle against Southern Front Custom Border Om elmiathin Factions & OtherKharaba Islamic Groups. Al Jeezah - Technically ISIS Attacks on the Opposition El Taebah Al Ramtha controlled areas is more dangerous for the Irbid Nassib Ghasamnearby countries.Mia`rbah Nasib Border - ISIS controlled areas not more than 213 km² & share borders with bothBusra "Jordan & Israeli Occupation areas in Syria". -

Situation Report: WHO Syria, Week 19-20, 2019

WHO Syria: SITUATION REPORT Weeks 32 – 33 (2 – 15 August), 2019 I. General Development, Political and Security Situation (22 June - 4 July), 2019 The security situation in the country remains volatile and unstable. The main hot spots remain Daraa, Al- Hassakah, Deir Ezzor, Latakia, Hama, Aleppo and Idlib governorates. The security situation in Idlib and North rural Hama witnessed a notable escalation in the military activities between SAA and NSAGs, with SAA advancement in the area. Syrian government forces, supported by fighters from allied popular defense groups, have taken control of a number of villages in the southern countryside of the northwestern province of Idlib, reaching the outskirts of a major stronghold of foreign-sponsored Takfiri militants there The Southern area, particularly in Daraa Governorate, experienced multiple attacks targeting SAA soldiers . The security situation in the Central area remains tense and affected by the ongoing armed conflict in North rural Hama. The exchange of shelling between SAA and NSAGs witnessed a notable increase resulting in a high number of casualties among civilians. The threat of ERWs, UXOs and Landmines is still of concern in the central area. Two children were killed, and three others were seriously injured as a result of a landmine explosion in Hawsh Haju town of North rural Homs. The general situation in the coastal area is likely to remain calm. However, SAA military operations are expected to continue in North rural Latakia and asymmetric attacks in the form of IEDs, PBIEDs, and VBIEDs cannot be ruled out. II. Key Health Issues Response to Al Hol camp: The Security situation is still considered as unstable inside the camp due to the stress caused by the deplorable and unbearable living conditions the inhabitants of the camp have been experiencing . -

Management in the Conflict-Torn Yarmouk Basin

1 QUANTITATIVE ASSESSMENT OF CONTESTED WATER USES AND 2 MANAGEMENT IN THE CONFLICT-TORN YARMOUK BASIN 1 2 3 4 3 Nicolas Avisse , Amaury Tilmant , David Rosenberg , and Samer Talozi 1 4 Ph.D., Department of Civil Engineering and Water Engineering, 1045 avenue de la Médecine, 5 Université Laval, Québec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada (corresponding author). Email: 6 [email protected] 2 7 Professor, Department of Civil Engineering and Water Engineering, 1045 avenue de la Médecine, 8 Université Laval, Québec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada. Email: [email protected] 3 9 Associate Professor, Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, 4110 Old Main Hill, 10 Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USA. Email: [email protected] 4 11 Associate Professor, Civil Engineering Department, Jordan University of Science and 12 Technology, Irbid 22110, Jordan. Email: [email protected] 13 ABSTRACT 14 The Yarmouk River basin is shared between Syria, Jordan, and Israel. Since the 1960s, Yarmouk 15 River flows have declined more than 85% despite the signature of bilateral agreements. Syria and 16 Jordan blame each other for the decline and have both developed their own explanatory narratives: 17 Jordan considers that Syria violated their 1987 agreement by building more dams than what was 18 agreed on, while Syria blames climate change. In fact, as the two countries do not share information, 19 neither on hydrological flows nor on water management, it is increasingly difficult to distinguish 20 between natural and anthropogenic factors affecting the flow regime. Remote sensing and multi- 21 agent simulation are combined to carry out an independent, quantitative, analysis of Jordanian 22 and Syrian competing narratives and show that a third cause for which there is no provision in 23 the bilateral agreements actually explains much of the changes in the flow regime: groundwater 24 over-abstraction by Syrian highland farmers. -

A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of Idps As a Result 0.Pdf

A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result About Syrians for Truth and Justice-STJ Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) is an independent, nongovernmental organization whose members include Syrian human rights defenders, advocates and academics of different backgrounds and nationalities. The initiative strives for SYRIA, where all Syrian citizens (males and females) have dignity, equality, justice and equal human rights . 1 A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result A flash report highlighting the bombardment on the western and eastern countryside of Daraa from 15 to 20 June 2018 2 A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result Preface With blatant disregard of all the warnings of the international community and UN, pro- government forces launched a major military escalation against Daraa Governorate, as from 15 to 20 June 2018. According to STJ researchers, many eyewitnesses and activists from Daraa, Syrian forces began to mount a major offensive against the armed opposition factions held areas by bringing reinforcements from various regions of the country a short time ago. The scale of these reinforcements became wider since June 18, 2018, as the Syrian regime started to send massive military convoys and reinforcements towards Daraa . Al-Harra and Agrabaa towns, as well as Kafr Shams city located in the western countryside of Daraa1, have been subjected to artillery and rocket shelling which resulted in a number of civilian causalities dead or wounded. Daraa’s eastern countryside2 was also shelled, as The Lajat Nahitah and Buser al Harir towns witnessed an aerial bombardment by military aircraft of the Syrian regular forces on June 19, 2018, causing a number of civilian casualties . -

The Death of 104 Individuals Under Torture in October 2015 99 Amongst Which Were Killed by Government Forces

SNHR is an independent, non-governmental, impartial human rights organization that was founded in June 2011. SNHR is a Monday, 2 November, 2015 certified source for the United Nation in all of its statistics. The Death of 104 Individuals under Torture in October 2015 99 amongst which were killed by government forces Report Contents: I. Report Methodology: I. Report Methodology II. Executive Summary Since 2011, the Syrian regime has refused to recognize any ar- III. The Most Significant rests it had made as it accused Al-Qaeda and the terrorist groups of committing these crimes. Also, the Syrian regime doesn’t Cases of Death Under Torture recognize any torture cases or torturing to death. SNHR acquire IV. Conclusions and its information from former prisoners and prisoners’ families Recommendations where most of the families get information about their beloved Acknowledgment and ones who are in prison by bribing the officials in charge. Condolences At SNHR, we rely on the families’ testimonies we get. How- ever, it should be noted that there are many cases where the Syrian authorities don’t give the families the dead bodies. Also, many families abstain from going to the military hospitals to bring the dead bodies of their beloved ones or even their be- longings out of fear that they might themselves get arrested. Also, most of the families assure use that their relatives were in good health when the arrest was made and it is highly unlikely that they died of an illness. Fadel Abdulghani, head of SNHR, says: “The principle of “Responsibility to Protect” must be implemented as the state has failed to protect its people and all the diplomatic and peaceful ef- forts have failed as well. -

PDF | 5.22 MB | English Version

Friday 1 January 2021 The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. M210101 Contents I. Background and Methodology...............................................................2 II. The Issues That Characterized 2020 According to the SNHR’s Database of Extrajudicial Killings...............................................................................5 III. Death Toll of Civilian Victims......................................................................7 IV. Death Toll of Victims Who Died Due to Torture, and Victims Amongst Media, Medical and Civil Defense Personnel...................................15 V. Record of Most Notable Massacres.....................................................30 VI. The Syrian Regime Bears Primary Responsibility for the Deaths of Syrian Citizens Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic............................................... 36 VII. The Most Notable Work Carried Out by SNHR on the Extrajudicial Killing Issue.........................................................................................................37 VIII. Conclusions and Recommendations ....................................................38 Extrajudicial Killing Claims the Lives of 1,734 Civilians in 2 Syria in 2020, Including 99 in December I. Background and Methodology: The documentation process to register victims killed in Syria is one of the most important roles performed by the Syrian -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013

United Nations S/2012/399 Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013 Original: English Identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, and 1 June 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 1 June 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 13-20334 (E) 110113 170113 *1320334* S/2012/399 Annex to the identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Friday, 1 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. At 2000 hours on 31 May 2012, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement personnel in Darayya, wounding two men. 2. At 2100 hours on 31 May 2012, an armed terrorist group attacked a law enforcement checkpoint in Malihah, wounding one man. 3. At 2300 hours on 31 May 2012, an armed terrorist group blocked roads and opened fire at random in Daf al-Shawk and Darayya. -

(CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-IZ-100-17-CA021 November 2017 Monthly Report Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, William Raynolds, Allison Cuneo, Kyra Kaercher, Darren Ashby, Gwendolyn Kristy, Jamie O’Connell, Nour Halabi Table of Contents: Executive Summary 2 Key Points 5 Syria 6 Iraq 7 Libya 8 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Executive Summary High levels of military activity were reported in Syria in November. SARG and pro-regime allies, backed by aerial bombardment, fought for control of ISIS-held al-Bukamal (Abu Kamal). Elements of Lebanese Hezbollah, the Iraqi Shia Popular Mobilization Front (PMF), and the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) participated in the military operations.2 This region of the Euphrates Valley contains significant ancient and modern cultural assets. Since the outbreak of the Syrian conflict, and especially since ISIS seized contriol of the area in 2014, cultural sites have been subjected to intense damage, deliberate destructions, and looting/thefts. The military operations did not result in significant increases in new data on the state of these cultural assets, and it is doubtful that a return to a loose system of regime control will significantly improve conditions in this remote, predominantly Sunni tribal region. Aerial bombardment increased over areas purportedly covered under the so-called Astana de- escalation agreements, bolstering “skepticism from opponents of the Syrian government.”3 During the reporting period aerial bombardment increased in opposition-held areas of Eastern Ghouta, Rif Dimashq Governorate, and in areas of Aleppo Governorate. -

Commentary on the EASO Country of Origin Information Reports on Syria (December 2019 – May 2020) July 2020

Commentary on the EASO Country of Origin Information Reports on Syria (December 2019 – May 2020) July 2020 1 © ARC Foundation/Dutch Council for Refugees, June 2020 ARC Foundation and the Dutch Council for Refugees publications are covered by the Create Commons License allowing for limited use of ARC Foundation publications provided the work is properly credited to ARC Foundation and the Dutch Council for Refugees and it is for non- commercial use. ARC Foundation and the Dutch Council for Refugees do not hold the copyright to the content of third party material included in this report. ARC Foundation is extremely grateful to Paul Hamlyn Foundation for its support of ARC’s involvement in this project. Feedback and comments Please help us to improve and to measure the impact of our publications. We’d be most grateful for any comments and feedback as to how the reports have been used in refugee status determination processes, or beyond: https://asylumresearchcentre.org/feedback/. Thank you. Please direct any questions to [email protected]. 2 Contents Introductory remarks ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Key observations ................................................................................................................................................ 5 General methodological observations and recommendations ......................................................................... 9 Comments on any forthcoming -

S/2021/282 Security Council

United Nations S/2021/282 Security Council Distr.: General 22 March 2021 Original: English United Nations Disengagement Observer Force Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report provides an account of the activities of the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) for the period from 20 November 2020 to 20 February 2021, pursuant to the mandate set out in Security Council resolution 350 (1974) and extended in subsequent Council resolutions, most recently resolution 2555 (2020). II. Situation in the area of operations and activities of the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force 2. During the reporting period, the ceasefire between Israel and the Syrian Arab Republic was generally maintained, despite several violations of the Agreement on Disengagement between Israeli and Syrian Forces of 1974. The overall security situation in the UNDOF area of operations was volatile, with continued military activity in the areas of separation and limitation, in violation of relevant Security Council resolutions, including resolution 2555 (2020). 3. In employing its best efforts to maintain the ceasefire and ensure that it is scrupulously observed, as prescribed in the Disengagement of Forces Agreement, UNDOF reports all breaches of the ceasefire line that it observes. All incidents of firing across the ceasefire line as well as the crossing of the ceasefire line by individuals, aircraft and drones constitute violations of the Agreement. In its regular interactions with both sides, the leadership of UNDOF continued to call upon the parties to exercise restraint and avoid any activities that might lead to an escalation of the situation between the parties. 4. -

Governance in Daraa, Southern Syria: the Roles of Military and Civilian Intermediaries

Governance in Daraa, Southern Syria: The Roles of Military and Civilian Intermediaries Abdullah Al-Jabassini Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 4 November 2019 2019/15 © European University Institute 2019 Content and individual chapters © Abdullah Al-Jabassini, 2019 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2019/15 4 November 2019 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Governance in Daraa, Southern Syria: The Roles of Military and Civilian Intermediaries Abdullah Al-Jabassini* * Abdullah Al-Jabassini is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the University of Kent. His doctoral research investigates the relationship between tribalism, rebel governance and civil resistance to rebel organisations with a focus on Daraa governorate, southern Syria. He is also a researcher for the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria project at the Middle East Directions Programme of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies.