Saudi Salafism and the Contested Ideologies of Muhammad Surur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

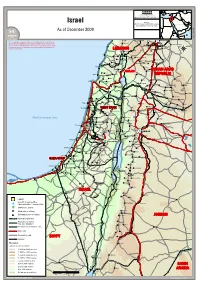

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

Territorial Control Map - Southern Front - 20 Feb 2017 Eldili Southern Fronts (SF) & Islamic Groups (IG)

Territorial Control Map - Southern Front - 20 Feb 2017 Eldili Southern Fronts (SF) & Islamic Groups (IG) Nawa Yarmouk Martyrs Brigade - ISIS Syrian Regime and Allied Militias Saidah Recently Captured by SF/IG Abu Hartin Ain Thakar Izraa Recently Captured by ISIS Buser al Harir Information Unit Information Al Shabrak El Shykh sa´ad Tasil Al Sheikh Maskin Melihit Al Atash Al Bunyan Al Marsous Adawan Garfah Military Operation Room Nafa`ah Israeli occupation Jamlah Ibtta Nahtah - Southern Front Factions, Islamic Opposition & Sahem El Golan Aabdyn HTS Launched (Death over Humiliation) Battle Al Shajarah Jillin Housing Daraa City, & captured Most of Al Manshia Alashaary Mlaiha el Sharqiah Baiyt Irah Jillin Dael El Sourah District & capturing part of the highway that lead Elmah Al Hrak Hayt Mlaihato (Customs el Garbiah Crossing Border), postponing by that Al Qussyr Tafas Khirbet Ghazaleh any Syrian Regime attempts to Re-Open it. Zaizon - First OfficialAl Darah reaction from Jordan Government Muzayrib Al Thaala was closing 90 KM of its borderAl Suwayda with Daraa & Quneitra against everyone, even injured civilians. Tal Shihab El Karak Western Ghariyah Al Yadudah Eastern Ghariyah - Military Operations Center (MOC) reaction was Athman putting pressure on Southern Front Factions to stop the battleUmm Wald or at least participating in it. Yarmouk Martyrs Brigade Elnaymah Al Musayfrah Daraa Saida Jbib Attacks on Opposition Kiheel Al Manshia - 20 Feb 2017 (Yarmouk Martyrs Brigade - ISIS) El SahoahLunched a new battle against Southern Front Custom Border Om elmiathin Factions & OtherKharaba Islamic Groups. Al Jeezah - Technically ISIS Attacks on the Opposition El Taebah Al Ramtha controlled areas is more dangerous for the Irbid Nassib Ghasamnearby countries.Mia`rbah Nasib Border - ISIS controlled areas not more than 213 km² & share borders with bothBusra "Jordan & Israeli Occupation areas in Syria". -

Management in the Conflict-Torn Yarmouk Basin

1 QUANTITATIVE ASSESSMENT OF CONTESTED WATER USES AND 2 MANAGEMENT IN THE CONFLICT-TORN YARMOUK BASIN 1 2 3 4 3 Nicolas Avisse , Amaury Tilmant , David Rosenberg , and Samer Talozi 1 4 Ph.D., Department of Civil Engineering and Water Engineering, 1045 avenue de la Médecine, 5 Université Laval, Québec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada (corresponding author). Email: 6 [email protected] 2 7 Professor, Department of Civil Engineering and Water Engineering, 1045 avenue de la Médecine, 8 Université Laval, Québec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada. Email: [email protected] 3 9 Associate Professor, Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, 4110 Old Main Hill, 10 Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USA. Email: [email protected] 4 11 Associate Professor, Civil Engineering Department, Jordan University of Science and 12 Technology, Irbid 22110, Jordan. Email: [email protected] 13 ABSTRACT 14 The Yarmouk River basin is shared between Syria, Jordan, and Israel. Since the 1960s, Yarmouk 15 River flows have declined more than 85% despite the signature of bilateral agreements. Syria and 16 Jordan blame each other for the decline and have both developed their own explanatory narratives: 17 Jordan considers that Syria violated their 1987 agreement by building more dams than what was 18 agreed on, while Syria blames climate change. In fact, as the two countries do not share information, 19 neither on hydrological flows nor on water management, it is increasingly difficult to distinguish 20 between natural and anthropogenic factors affecting the flow regime. Remote sensing and multi- 21 agent simulation are combined to carry out an independent, quantitative, analysis of Jordanian 22 and Syrian competing narratives and show that a third cause for which there is no provision in 23 the bilateral agreements actually explains much of the changes in the flow regime: groundwater 24 over-abstraction by Syrian highland farmers. -

I Am a Salafi : a Study of the Actual and Imagined Identities of Salafis

The Hashemite Kingdom Jordan The Deposit Number at The National Library (2014/5/2464) 251.541 Mohammad Abu Rumman I Am A Salafi A Study of The Actual And Imagined Identities of Salafis / by Mohammad Abu Rumman Amman:Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2014 Deposit No.:2014/5/2464 Descriptors://Islamic Groups//Islamic Movement Published in 2014 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Jordan & Iraq FES Jordan & Iraq P.O. Box 941876 Amman 11194 Jordan Email: [email protected] Website: www.fes-jordan.org Not for sale © FES Jordan & Iraq All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely those of the original author. They do not necessarily represent those of the Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung or the editor. Translation: Dr. Hassan Barari Editing: Amy Henderson Cover: YADONIA Group Printing: Economic Printing Press ISBN: 978-9957-484-41-5 2nd Edition 2017 2 I AM A SALAFI A Study of the Actual and Imagined Identities of Salafis by Mohammad Abu Rumman 3 4 Dedication To my parents Hoping that this modest endeavor will be a reward for your efforts and dedication 5 Table of Contents DEDICATION ........................................................................................................ 5 FOREWORD .......................................................................................................... 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................ -

Khashoggi's Death and Its Repercussions on the Saudi Position with Turkey

ORSAM Analysis No: 224 / January 2019 KHASHOGGI’S DEATH AND ITS REPERCUSSIONS ON THE SAUDI POSITION WITH TURKEY IHAB OMAR ORSAM Copyright Ankara - TURKEY ORSAM © 2019 Content of this publication is copyrighted to ORSAM. Except reasonable and partial quotation and use under the Act No. 5846, Law on Intellectual and Artistic Works, via proper citation, the content may not be used or re-published without prior permission by ORSAM. The views ex- pressed in this publication reflect only the opinions of its authors and do not represent the institu- tional opinion of ORSAM. ISBN:978-605-80419-3-6 Center for Middle Eastern Studies Adress : Mustafa Kemal Mah. 2128 Sk. No: 3 Çankaya, ANKARA Phone: +90 (312) 430 26 09 Faks: +90 (312) 430 39 48 Email: [email protected] Photos: Associated Press Analiz No:224 ORSAM ANALYSIS KHASHOGGI 'S DEATH AND ITS REPERCUSSIONS ON THE SAUDI POSITION WITH TURKEY About the Author Ihab Omar Ihab Omar is an Egyptian journalist and researcher specializing in Arab affairs. He holds a Bachelor of Media degree and General Diploma in Education. He covered the Arab events of many Arab newspapers and international sites. He covered closely the events of the Arab Spring in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen. January 2019 orsam.org.tr 2 Khashoggi's Death and its Repercussions on the Saudi Position With Turkey Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................3 Who was Jamal Khashoggi? ..........................................................................................................3 -

Appendix 2: Evidence Submitted to the FFP

Appendix 2: Evidence submitted to the FFP Human Rights Watch Page 1. HRW's written submission 1 2. The High Cost of Change 13 3. Prominent detainees held incommunicado 35 4. Saudi Arabia allow access to detained women 39 activists 5. Saudi Arabia free adult children of ex- official 43 Freedom Now submissions in relation to Loujain al-Hathloul Page 6. An English translation of the charges against Loujain 46 al-Hathloul 7. Freedom Now’s petition to the UN Working Group on 51 Arbitrary Detention on behalf of Loujain al-Hathloul 8. Saudi Arabia's response to Freedom Now’s petition 83 (provided by the Saudi government to the UN Working Group) 9. Freedom Now's comments on Saudi Arabia's response 95 10. The opinion of the UN Working Group – 12 June 2020 111 Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN) Page 11. Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN) 127 submission Grant Liberty report- December 2020 Page 12. Grant Liberty report- December 2020 130 MENA Rights Group Page 13. MENA Rights Group submission on Messrs Salman Al 171 Saud and Abdulaziz Al Saud Human Rights Watch Page 1 of 174 Human Rights Watch Memo for Fact Finding Panel – Investigation in the Detention of Former Crown Prince Mohammed bin Nayef and Prince Ahmed bin Abdulaziz I. Summary of Repression Under the De Facto Rule of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman In the summer of 2017, Mohammed bin Salman ousted his cousin Mohammed bin Nayef from power and became crown prince. Almost immediately the authorities began to purge former security and intelligence officials and quietly reorganized the country’s prosecution service and security apparatus, the primary tools of Saudi repression, and placed them directly under the royal court’s oversight. -

In This Issue

VOLUME VII, ISSUE 36 u NOVEMBER 25, 2009 IN THIS ISSUE: BRIEFS...................................................................................................................................1 IBRAHIM AL-RUBAISH: NEW RELIGIOUS IDEOLOGUE OF AL-QAEDA IN SAUDI ARABIA CALLS FOR REVIVAL OF ASSASSINATION TACTIC By Murad Batal al-Shishani..................................................................................................3 AL-QAEDA IN IRAQ OPERATIONS SUGGEST RISING CONFIDENCE AHEAD OF U.S. MILITARY WITHDRAWAL Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) By Ramzy Mardini..........................................................................................................4 FRENCH OPERATION IN AFGHANISTAN AIMS TO OPEN NEW COALITION SUPPLY ROUTE Terrorism Monitor is a publication By Andrew McGregor............................................................................................................6 of The Jamestown Foundation. The Terrorism Monitor is TALIBAN EXPAND INSURGENCY TO NORTHERN AFGHANISTAN designed to be read by policy- makers and other specialists By Wahidullah Mohammad.................................................................................................9 yet be accessible to the general public. The opinions expressed within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily LEADING PAKISTANI ISLAMIST ORGANIZING POPULAR MOVEMENT reflect those of The Jamestown AGAINST SOUTH WAZIRISTAN OPERATIONS Foundation. As the Pakistani Army pushes deeper into South Waziristan, a vocal political Unauthorized reproduction or challenge -

Saudi Arabia

FREEDOM ON THE NET 2017 Saudi Arabia 2016 2017 Population: 32.3 million Not Not Internet Freedom Status Internet Penetration 2016 (ITU): 73.8 percent Free Free Social Media/ICT Apps Blocked: Yes Obstacles to Access (0-25) 14 14 Political/Social Content Blocked: Yes Limits on Content (0-35) 24 24 Bloggers/ICT Users Arrested: Yes Violations of User Rights (0-40) 34 34 TOTAL* (0-100) 72 72 Press Freedom 2017 Status: Not Free * 0=most free, 100=least free Key Developments: June 2016 – May 2017 • The government outlined plans to significantly increase broadband penetration by 2020 (see Availability and Ease of Access). • An online campaign to end male guardianship caught the attention of the royal court and resulted in gradual reforms (see Digital Activism). • A court increased an activist’s prison sentence for advocating for human rights online from 9 to 11 years on appeal; others were newly detained (see Prosecutions and Detentions for Online Activities). • Public institutions lost critical data in major cyberattacks, including the civil aviation authority, a chemical company, and the labor ministry (see Technical Attacks). 1 www.freedomonthenet.org Introduction FREEDOM SAUDI ARABIA ON THE NET Obstacles to Access 2017 Introduction Availability and Ease of Access Saudi internet freedom remained restricted in 2017, despite effective digital activism for women’s Restrictions on Connectivity rights. Several human rights defenders were jailed for social media posts. Saudi Arabia unveiled its monumental “Vision 2030” reform and development targets in April 2016. ICT Market The plan included measures to increase competitiveness, foreign direct investment, and non-oil government revenue by 2030.1 The government also announced a National Transformation Program in June 2016 which included several ICT specific targets to be achieved by 2020, including increasing Regulatory Bodies fixed-line broadband penetration in densely populated areas from 44 to 80 percent, and increasing wireless broadband penetration in rural areas from 12 to 70 percent. -

From the Heart of the Syrian Crisis

From the Heart of the Syrian Crisis A Report on Islamic Discourse Between a Culture of War and the Establishment of a Culture of Peace Research Coordinator Sheikh Muhammad Abu Zeid From the Heart of the Syrian Crisis A Report on Islamic Discourse Between a Culture of War and the Establishment of a Culture of Peace Research Coordinator Sheikh Muhammad Abu Zeid Adyan Foundation March 2015 Note: This report presents the conclusion of a preliminary study aimed at shedding light on the role of Sunni Muslim religious discourse in the Syrian crisis and understanding how to assess this discourse and turn it into a tool to end violence and build peace. As such, the ideas in the report are presented as they were expressed by their holders without modification. The report, therefore, does not represent any official intellectual, religious or political position, nor does it represent the position of the Adyan foundation or its partners towards the subject or the Syrian crisis. The following report is simply designed to be a tool for those seeking to understand the relationship between Islamic religious discourse and violence and is meant to contribute to the building of peace and stability in Syria. It is, therefore, a cognitive resource aimed at promoting the possibilities of peace within the framework of Adyan Foundation’s “Syria Solidarity Project” created to “Build Resilience and Reconciliation through Peace Education”. The original text of the report is in Arabic. © All rights reserved for Adyan Foundation - 2015 Beirut, Lebanon Tel: 961 1 393211 -

CTC Sentinel Objective

OCTOBER 2011 . VOL 4 . ISSUE 10 COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT CTC Sentinel OBJECTIVE . RELEVANT . RIGOROUS Contents Insights from Bin Ladin’s FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Insights from Bin Ladin’s Audiocassette Audiocassette Library in Library in Kandahar By Flagg Miller Kandahar REPORTS By Flagg Miller 5 India’s Approach to Counterinsurgency and the Naxalite Problem By Sameer Lalwani 9 Evaluating Pakistan’s Offensives in Swat and FATA By Daud Khattak 12 The Enduring Appeal of Al-`Awlaqi’s “Constants on the Path of Jihad” By J.M. Berger 15 The Decline of Jihadist Activity in the United Kingdom By James Brandon 17 Understanding the Role of Tribes in Yemen By Charles Schmitz 22 Al-Shabab’s Setbacks in Somalia By Christopher Anzalone 25 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts s the world waits for the After the tapes were reviewed by U.S. declassification of documents intelligence agencies shortly after their from Usama bin Ladin’s acquisition, the collection was sold to the Abbottabad residence in Williams College Afghan Media Project APakistan, an earlier archive shedding run by American anthropologist David valuable light on al-Qa`ida’s formation Edwards. This author began cataloguing under Bin Ladin is slowly being and archiving the collection in 2003, as released. Acquired by the Cable News soon as the tapes arrived at the college, Network in early 2002 from Bin Ladin’s and is currently writing a book about the About the CTC Sentinel Kandahar compound, more than 1,500 figuration of Bin Ladin’s leadership and The Combating Terrorism Center is an audiocassettes are being made available al-Qa`ida through the archive. -

Challenges to Al Qaeda Leadership of the Jihadist Community

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2014 Vanguards No Longer: Challenges to al Qaeda Leadership of the Jihadist Community Byron J. Doerfer Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Doerfer, Byron J., "Vanguards No Longer: Challenges to al Qaeda Leadership of the Jihadist Community". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2014. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/382 Vanguards No Longer: Challenges to al Qaeda Leadership of the Jihadist Community By Byron Doerfer Submitted to the International Studies Program, Trinity College Supervised by Professor Isaac Kamola ©2014 Abstract 2014 marks the first time that al Qaeda’s supremacy in the Jihadist community has been challenged. al Qaeda’s former franchise in Iraq, now called the “Islamic State,” has declared the organization responsible for 9/11 “Tyrants” and “Apostates.” The Islamic State has begun openly attacking al Qaeda’s official franchise in Syria, Jabhat al Nusra. These events are a consequence of the strategy of franchising that al Qaeda undertook following 9/11. The root of the issue between al Qaeda and its former Iraqi franchise is over a difference over the importance placed on popular support as a key ingredient in achieving the larger objectives of Global Jihad. This schism in the jihadist community will have a large impact on al Qaeda, as well as implications for United States security policy. i Introduction Introduction 2014 has brought a series of events that will fundamentally change the way the world views the terrorist organization known as Al Qaeda.