Stradivari Exhibition at the Musical Instrument Museum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz

CoNSERVATORY oF Music presents The Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz SPOTLIGHT ON YOUNG VIOLIN VIRTUOSI with Tao Lin, piano Saturday, April 3, 2004 7:30p.m. Amamick-Goldstein Concert Hall de Hoernle International Center Program Polonaise No. 1 in D Major ..................................................... Henryk Wieniawski Gabrielle Fink, junior (United States) (1835 - 1880) Tambourin Chino is ...................................................................... Fritz Kreisler Anne Chicheportiche, professional studies (France) (1875- 1962) La Campanella ............................................................................ Niccolo Paganini Andrei Bacu, senior (Romania) (1782-1840) (edited Fritz Kreisler) Romanza Andaluza ....... .. ............... .. ......................................... Pablo de Sarasate Marcoantonio Real-d' Arbelles, sophomore (United States) (1844-1908) 1 Dance of the Goblins .................................................................... Antonio Bazzini Marta Murvai, senior (Romania) (1818- 1897) Caprice Viennois ... .... ........................................................................ Fritz Kreisler Danut Muresan, senior (Romania) (1875- 1962) Finale from Violin Concerto No. 1 in g minor, Op. 26 ......................... Max Bruch Gareth Johnson, sophomore (United States) (1838- 1920) INTERMISSION 1Ko<F11m'1-za from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor .................... Henryk Wieniawski ten a Ilieva, freshman (Bulgaria) (1835- 1880) llegro a Ia Zingara from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor -

Stowell Make-Up

The Cambridge Companion to the CELLO Robin Stowell Professor of Music, Cardiff University The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP,United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Adobe Minion 10.75/14 pt, in QuarkXpress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0 521 621011 hardback ISBN 0 521 629284 paperback Contents List of illustrations [page viii] Notes on the contributors [x] Preface [xiii] Acknowledgements [xv] List of abbreviations, fingering and notation [xvi] 21 The cello: origins and evolution John Dilworth [1] 22 The bow: its history and development John Dilworth [28] 23 Cello acoustics Bernard Richardson [37] 24 Masters of the Baroque and Classical eras Margaret Campbell [52] 25 Nineteenth-century virtuosi Margaret Campbell [61] 26 Masters of the twentieth century Margaret Campbell [73] 27 The concerto Robin Stowell and David Wyn Jones [92] 28 The sonata Robin Stowell [116] 29 Other solo repertory Robin Stowell [137] 10 Ensemble music: in the chamber and the orchestra Peter Allsop [160] 11 Technique, style and performing practice to c. -

Messiah Notes.Indd

Take One... The Messiah Violin Teacher guidance notes The Messiah Violin is on display in A zoomable image of the violin is available Gallery 39, Music and Tapestry. on our website. Visit www.ashmolean.org/education/ Starting Questions The following questions may be useful as a starting point for thinking about the Messiah violin and developing speaking and listening skills with your class. • What materials do you think this violin is made from? • Why do you think this violin is in a museum? • Where do you think it might come from? • What kind of person do you think would have owned this violin? • Who could have made it? • Does the violin look like it has been played a lot or does it look brand new? • How old do you think the violin could be? • If I told you that nobody is allowed to play this violin do you feel about that? These guidance notes are designed to help you use the Ashmolean’s Messiah violin as a focus for cross-curricular teaching and learning. A visit to the Ashmolean Museum to see your chosen object offers your class the perfect ‘learning outside the classroom’ opportunity. Background Information Italy - a town that was already famous for its master violin makers. The new styles of violins and cellos that The Object he developed were remarkable for their excellent tonal quality and became the basic design for many TThe Messiah violin dates from Stradivari’s ‘golden modern versions of the instruments. period’ of around 1700 - 1725. The violin owes Stradivari’s violins are regarded as the fi nest ever its fame chiefl y to its fresh appearance due to the made. -

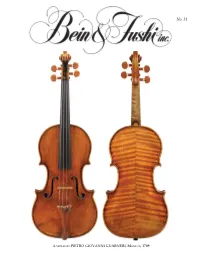

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri

141 A VIOLIN BY GIUSEPPE GIOVANNI BATTISTA GUARNERI Roger Hargrave, who has also researched and drawn the enclosed poster, discusses an outstanding example of the work of a member of the Guarneri family known as `Joseph Guarneri filius Andrea'. Andrea Guarneri was the first He may never have many details of instruments by of the Guarneri family of violin reached the heights of his Joseph filius at this period recall makers and an apprentice of contemporary, the Amati school, this type of Nicola Amati (he was actually varnish, in combination with registered as living in the house Antonio Stradivarius, but he the freer hand of Joseph, gives of Nicola Amati in 1641). Andrea's does rank as one of the the instruments a visual impact youngest son, whose work is il - greatest makers of all time. never achieved by an Amati or , lustrated here, was called. We should not forget he with the exception of Stradi - Giuseppe. Because several of the sired and trained the great vari, by any other classical Guarneri family bear the same del Gesu' maker before this time. christian names, individuals have traditionally been identified by a It should be said, however, suffix attached to their names. that the varnish of Joseph filius Thus, Giuseppe's brother is known as `Peter Guarneri varies considerably. It is not always of such out - of Mantua' to distinguish him from Giuseppe's son, standing quality the same can be said of Joseph's pro - who is known as `Peter Guarneri of Venice'. duction in general. If I were asked to describe the instruments of a few of the great Cremonese makers Giuseppe himself is called 'Giuseppe Guarneri filius in a single word, I would say that Amatis (all of them) Andrea' or, more simply, `Joseph filius' to distinguish are `refined', Stradivaris are `stately', del Gesus are him from his other son, the illustrious 'Giuseppe `rebellious' and the instruments of Joseph filius An - Guarneri del Gesu'. -

Rachel Barton Violin Patrick Sinozich, Piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 041 INSTRUMENT of the DEVIL 1 Saint-Saëns: Danse Macabre, Op

Cedille Records CDR 90000 041 Rachel Barton violin Patrick Sinozich, piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 041 INSTRUMENT OF THE DEVIL 1 Saint-Saëns: Danse Macabre, Op. 40 (7:07) Tartini: Sonata in G minor, “The Devil’s Trill”* (15:57) 2 I. Larghetto Affectuoso (5:16) 3 II. Tempo guisto della Scuola Tartinista (5:12) 4 III. Sogni dellautore: Andante (5:25) 5 Liszt/Milstein: Mephisto Waltz (7:21) 6 Bazzini: Round of the Goblins, Op. 25 (5:05) 7 Berlioz/Barton-Sinozich: Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath from Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14 (10:51) 8 De Falla/Kochanski: Dance of Terror from El Amor Brujo (2:11) 9 Ernst: Grand Caprice on Schubert’s Der Erlkönig, Op. 26 (4:11) 10 Paganini: The Witches, Op. 8 (10:02) 1 1 Stravinsky: The Devil’s Dance from L’Histoire du Soldat (trio version)** (1:21) 12 Sarasate: Faust Fantasy (13:30) Rachel Barton, violin Patrick Sinozich, piano *David Schrader, harpsichord; John Mark Rozendaal, cello **with John Bruce Yeh, clarinet TT: (78:30) Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foun- dation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are supported in part by grants from the WPWR-TV Chan- nel 50 Foundation and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. Zig and zig and zig, Death in cadence Knocking on a tomb with his heel, Death at midnight plays a dance tune Zig and zig and zig, on his violin. -

Antonio Stradivari "Servais" 1701

32 ANTONIO STRADIVARI "SERVAIS" 1701 The renowned "Servais" cello by Stradivari is examined by Roger Hargrave Photographs: Stewart Pollens Research Assistance: Julie Reed Technical Assistance: Gary Sturm (Smithsonian Institute) In 184.6 an Englishman, James Smithson, gave the bines the grandeur of the pre‑1700 instrument with US Government $500,000 to be used `for the increase the more masculine build which we could wish to and diffusion of knowledge among men.' This was the have met with in the work of the master's earlier beginning of the vast institution which now domi - years. nates the down‑town Washington skyline. It includes the J.F. Kennedy Centre for Performing Arts and the Something of the cello's history is certainly worth National Zoo, as well as many specialist museums, de - repeating here, since, as is often the case, much of picting the achievements of men in every conceiv - this is only to be found in rare or expensive publica - able field. From the Pony Express to the Skylab tions. The following are extracts from the Reminis - orbital space station, from Sandro Botticelli to Jack - cences of a Fiddle Dealer by David Laurie, a Scottish son Pollock this must surely be the largest museum violin dealer, who was a contemporary of J.B. Vuil - and arts complex anywhere in the world. Looking laume: around, one cannot help feeling that this is the sort While attending one of M. Jansen's private con - of place where somebody might be disappointed not certs, I had the pleasure of meeting M. Servais of Hal, to find the odd Strad! And indeed, if you can manage one of the most renowned violoncellists of the day . -

Die Sammlung Historischer Streichinstrumente Der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank

OESTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBANK EUROSYSTEM Die Sammlung historischer Streichinstrumente der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank The collection of Historical String Instruments of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Inhaltsverzeichnis Contents Impressum Medieninhaberin: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Otto-Wagner-Platz 3, 1090 Wien, T: (+43 1) 404 20-6605, F: (+43 1) 404 20-6697, www.oenb.at Redaktion: Mag. Brigitte Alizadeh-Gruber, Muna Kadum, Martina Leitner, Mag. Irene Mühldorf Grafik, Layout und Satz: Melanie Schuhmacher Fotos: © Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien Druck: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Abteilung für Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und Publikationen, Gruppe Multimedia-, Internet- und Print-Service. © Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2013. Streichinstrumente/ String Instruments 9 Amati Andrea 10 Violoncello, Cremona, spätes 16. Jh. 10 Bergonzi Carlo 12 Violine, Cremona 1723 12 Violine, Cremona nach 1724 14 Bergonzi Michelangelo 16 Violine, Cremona um 1740 16 Violine, „ex Hamma-Segelman“, Cremona um 1750 18 Camilli Camillus 20 Violine, Mantua 1736 20 Ceruti Giovanni Battista 22 Viola, Cremona um 1810 22 Gagliano Alessandro 24 Violoncello, Neapel ca. 1710 24 Grancino Giovanni 26 Violoncello, „ex Piatti“ – „ex Dunlop“, Mailand 1706 26 Guadagnini Giovanni Battista 28 Violoncello, „ex von Zweygberg“, Piacenza 174. 28 Violine, Mailand 1749 30 Violine, „ex Meinel“, Turin um 1770–1775 32 Violine, Turin 1772 34 Violine, „Mantegazza“, Turin 1774 36 Violine, Turin 177. 38 Viola, Turin 1784 40 Guarneri Andrea 42 Violine, Cremona, Mitte 17. Jh. 42 Guarneri del Gesù Giuseppe 44 Violine, „ex Sorkin“, Cremona 1731 44 Violine, „ex Guilet“, Cremona nach 1732 46 Violine, „ex Carrodus“, Cremona 1741 48 Lorenzini Gaspare 50 Violine, Piacenza um 1760 50 Maggini Giovanni Paolo 52 Viola, Brescia, frühes 17. Jh. 52 Montagnana Domenico 54 Violine, Venedig 1727 54 Seraphin Sanctus 56 Violine, Venedig 1733 56 Violine, „ex Hamma“, Venedig nach 1748 58 Silvestre Pierre 60 Violine, „ex Moser“, Lyon ca. -

BAZZINI Complete Opera Transcriptions

95674 BAZZINI Complete Opera Transcriptions Anca Vasile Caraman violin · Alessandro Trebeschi piano Antonio Bazzini 1818-1897 CD1 65’09 CD4 61’30 CD5 53’40 Bellini 4. Fantaisie de Concert Mazzucato and Verdi Weber and Pacini Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 (Il pirata) Op.27 15’08 1. Fantaisie sur plusieurs thêmes Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 1. No.1 – Casta Diva (Norma) 7’59 de l’opéra de Mazzucato 1. No.5 – Act 2 Finale of 2. No.6 – Quartet CD3 58’41 (Esmeralda) Op.8 15’01 Oberon by Weber 7’20 from I Puritani 10’23 Donizetti 2. Fantasia (La traviata) Op.50 15’55 1. Fantaisie dramatique sur 3. Souvenir d’Attila 16’15 Tre fantasie sopra motivi della Saffo 3. Adagio, Variazione e Finale l’air final de 4. Fantasia su temi tratti da di Pacini sopra un tema di Bellini Lucia di Lammeroor Op.10 13’46 I Masnadieri 14’16 2. No.1 11’34 (I Capuleti e Montecchi) 16’30 3. No.2 14’59 4. Souvenir de Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 4. No.3 19’43 Beatrice di Tenda Op.11 16’11 2. No.2 – Variations brillantes 5. Fantaisia Op.40 (La straniera) 14’02 sur plusieurs motifs (La figlia del reggimento) 9’44 CD2 65’16 3. No.3 – Scène et romance Bellini (Lucrezia Borgia) 11’05 Anca Vasile Caraman violin · Alessandro Trebeschi piano 1. Variations brillantes et Finale 4. No.4 – Fantaisie sur la romance (La sonnambula) Op.3 15’37 et un choeur (La favorita) 9’02 2. -

Reconstructing Lost Instruments Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum and the Violin Family C

Prejeto / received: 3. 5. 2019. Odobreno / accepted: 12. 9. 2019. doi: 10.3986/dmd15.1-2.07 RECONSTRUCTING LOST INSTRUMENTS Praetorius’S Syntagma musicum and the Violin Family C. 1619 Matthew Zeller Duke University Izvleček: Knjigi De organographia in Theatrum Abstract: Michael Praetorius’s De organographia instrumentorum Michaela Praetoriusa vsebujeta and Theatrum instrumentorum provide valuable dragocene namige, ki pomagajo pri poznavanju clues that contribute to a new understanding glasbil iz družine violin okoli leta 1619; številna of the violin family c. 1619, many surviving ex- preživela glasbila so manjša, kot so bili izvirniki amples of which are reduced in size from their v 16. in 17. stoletju. Podatki o preživelih glas- sixteenth- and seventeenth-century dimensions. bilih – predvsem izdelki družine Amati – skupaj The record of surviving instruments – especially z metrologijo, sekundarno dokumentacijo in those of the Amati family – alongside metrologic, ikonografskim gradivom kažejo na to, da je documentary and iconographic evidence shows Michael Praetorius opisal veliko glasbilo, po that Michael Praetorius describes a large in- velikosti izjemno podobno violončelu (basso strument conforming remarkably well to the da braccio),kar je odličen primer predstavitve original dimensions of the basso da braccio glasbila iz družine violin in točne uglasitve, kot (violoncello), as well as furnishing an excellent so jih poznali v času izida Praetoriusovega dela. scale representation of the violin family as it was at the time of these works’ -

Syrinx (Debussy) Body and Soul (Johnny Green)

Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Hurrian Hymn from Ancient Mesopotamian Spring 2020 Musical Fragment c. 1440 BCE D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Shadow of the Ziggurat Assyrian Hammered Lyre Spring 2020 (Replica) D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Hymn to Horus Replica Ancient Lyre Spring 2020 Based on Trad. Eqyptian Folk Melody D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Roman Banquet Replica Kithara Spring 2020 Orig Composition in Hypophrygian Mode D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Spring 2020 D. H. Tracy If You Missed a Session…. • PDF’s of previous presentations – Also other handout materials are on the OLLI Course website: http://olli.illinois.edu/downloads/courses/ The Sound of Music Syllabus.pdf References for Sound of Music OLLI Course Spring 2020.pdf Smartphone Apps for Sound of Music.pdf Musical Scale Cheat Sheet.pdf OLLI Musical Scale Slider Tool.pdf SoundOfMusic_1 handout.pdf SoM_2_handout.pdf SoM_3 handout.pdf SoM_4 handout.pdf 2/25/20 Sound of Music 5 6 Course Outline 1. Building Blocks: Some basic concepts 2. Resonance: Building Sounds 3. Hearing and the Ear 4. Musical Scales 5. Musical Instruments 6. Singing and Musical Notation 7. Harmony and Dissonance; Chords 8. Combining the Elements of Music 2/25/20 Sound of Music 5 7 Chicago Symphony Orchestra (2015) 2/25/20 Sound of Music -

A Prima Vista

A PRIMA VISTA a survey of reprints and of recent publications 2002/1 BROEKMANS & VAN POPPEL Van Baerlestraat 92-94 Postbus 75228 1070 AE AMSTERDAM sheet music: 020-6796575 CDs: 020-6751653/fax: 020-6646759 also on INTERNET: www.broekmans.com e-mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS A PRIMA VISTA 2002/1 PAGE HEADING 03 PIANO 2-HANDS 07 PIANO 4-HANDS, 2 AND MORE PIANOS, HARPSICHORD 08 ORGAN 09 KEYBOARD 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 10 VIOLIN SOLO, VIOLA SOLO 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 11 VIOLIN WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 12 VIOLIN PLAY-ALONG 13 VIOLA WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, CELLO WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 14 VIOLA DA GAMBA WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 14 2 AND MORE STRING INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 18 FLUTE SOLO, OBOE SOLO 19 CLARINET SOLO, SAXOPHONE SOLO, BASSOON SOLO, TRUMPET SOLO 20 HORN SOLO, TROMBONE SOLO, TUBA SOLO 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 20 PICCOLO WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, FLUTE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 22 FLUTE PLAY-ALONG, ALTO FLUTE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 23 OBOE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, OBOE PLAY-ALONG, CLARINET WIT ACCOMPANIMENT 24 CLARINET PLAY-ALONG 25 BASSETHORN WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, SAXOPHONE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 27 SAXOPHONE PLAY-ALONG 28 BASSOON WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, TRUMPET WIT ACCOMPANIMENT 29 TRUMPET PLAY-ALONG, HORN WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 30 TROMBONE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, TROMBONE PLAY-ALONG 31 TUBA WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, EUPHONIUM PLAY-ALONG 2 AND MORE WIND INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 31 2 AND MORE WOODWIND