The Magnitude and Diversity of Infectious Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ID 2 | Issue No: 4.1 | Issue Date: 29.10.14 | Page: 1 of 24 © Crown Copyright 2014 Identification of Corynebacterium Species

UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations Identification of Corynebacterium species Issued by the Standards Unit, Microbiology Services, PHE Bacteriology – Identification | ID 2 | Issue no: 4.1 | Issue date: 29.10.14 | Page: 1 of 24 © Crown copyright 2014 Identification of Corynebacterium species Acknowledgments UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations (SMIs) are developed under the auspices of Public Health England (PHE) working in partnership with the National Health Service (NHS), Public Health Wales and with the professional organisations whose logos are displayed below and listed on the website https://www.gov.uk/uk- standards-for-microbiology-investigations-smi-quality-and-consistency-in-clinical- laboratories. SMIs are developed, reviewed and revised by various working groups which are overseen by a steering committee (see https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/standards-for-microbiology-investigations- steering-committee). The contributions of many individuals in clinical, specialist and reference laboratories who have provided information and comments during the development of this document are acknowledged. We are grateful to the Medical Editors for editing the medical content. For further information please contact us at: Standards Unit Microbiology Services Public Health England 61 Colindale Avenue London NW9 5EQ E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://www.gov.uk/uk-standards-for-microbiology-investigations-smi-quality- and-consistency-in-clinical-laboratories UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations are produced in association with: Logos correct at time of publishing. Bacteriology – Identification | ID 2 | Issue no: 4.1 | Issue date: 29.10.14 | Page: 2 of 24 UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations | Issued by the Standards Unit, Public Health England Identification of Corynebacterium species Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................... -

Granuloma De Las Piscinas Carcinoma Basocelular Localmente Avanzado

Penfigoide gestacional pustuloso Granuloma facial de localización atípica Programa de Educación Médica Continua Variantes de Archivos Argentinos de Dermatología clínicas inusuales de Año 2019, volumen 5, número 4 sarcoidosis Octubre, Noviembre y Diciembre 2019. cutánea Precio: $200 Carcinoma basocelular localmente avanzado tratado con Vismodegib Granuloma de las piscinas www.archivosdermato.org.ar [email protected] Educando Nos Programa de Educación Médica Continua de Archivos Argentinos de Dermatología Año 2019, volumen 5, número 4 Sumario Octubre, Noviembre y Diciembre 2019 Editorial Acrodermatitis enteropática 3 Glorio Roberto 36 Ruiz Díaz María, Kuen Bernardita, Caggia Antonella, Díaz Ysabel, Lozinsky Liliana 4 Reglamento de publicaciones Jornadas de Educación 40 Médica Continua Granuloma facial de 6 localización atípica Carcinoma basocelular Digilio Marianela, Manzano Roxana, Bendjuia Gabriela, 42 localmente avanzado tratado Schroh Roberto, Feinsilber Daniel con Vismodegib Van Caester Leandro Rodolfo, Alfaro María Florencia, Consigli Javier, De La Colina Marcelo, Manrique Valeria, Variantes clínicas inusuales de Pereyra Susana Beatriz 10 sarcoidosis cutánea Espósito Daniela, Márquez, Juan Manuel, López Di Noto Ada Laura, Marcucci Carolina, Sánchez Graciela, Merola Gladys Seguimiento en pacientes 46 sensibilizados a Queratosis folicular invertida de metilisotiazolinona 18 localización infrecuente Russo Juan Pedro, Palazzolo Juan Francisco, Adorni Romina, Consigli Carlos Landau Débora, Caruso Territoriale Antonella, Valente -

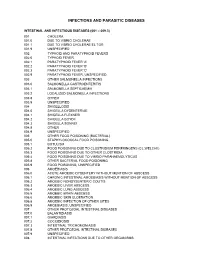

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

High Quality Permanent Draft Genome Sequence of Chryseobacterium Bovis DSM 19482T, Isolated from Raw Cow Milk

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title High quality permanent draft genome sequence of Chryseobacterium bovis DSM 19482T, isolated from raw cow milk. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4b48v7v8 Journal Standards in genomic sciences, 12(1) ISSN 1944-3277 Authors Laviad-Shitrit, Sivan Göker, Markus Huntemann, Marcel et al. Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.1186/s40793-017-0242-6 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Laviad-Shitrit et al. Standards in Genomic Sciences (2017) 12:31 DOI 10.1186/s40793-017-0242-6 SHORT GENOME REPORT Open Access High quality permanent draft genome sequence of Chryseobacterium bovis DSM 19482T, isolated from raw cow milk Sivan Laviad-Shitrit1, Markus Göker2, Marcel Huntemann3, Alicia Clum3, Manoj Pillay3, Krishnaveni Palaniappan3, Neha Varghese3, Natalia Mikhailova3, Dimitrios Stamatis3, T. B. K. Reddy3, Chris Daum3, Nicole Shapiro3, Victor Markowitz3, Natalia Ivanova3, Tanja Woyke3, Hans-Peter Klenk4, Nikos C. Kyrpides3 and Malka Halpern1,5* Abstract Chryseobacterium bovis DSM 19482T (Hantsis-Zacharov et al., Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58:1024-1028, 2008) is a Gram-negative, rod shaped, non-motile, facultative anaerobe, chemoorganotroph bacterium. C. bovis is a member of the Flavobacteriaceae, a family within the phylum Bacteroidetes. It was isolated when psychrotolerant bacterial communities in raw milk and their proteolytic and lipolytic traits were studied. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the draft genome sequence and annotation. The DNA G + C content is 38.19%. The chromosome length is 3,346,045 bp. It encodes 3236 proteins and 105 RNA genes. The C. bovis genome is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Type Strains, Phase I: the one thousand microbial genomes study. -

Parasite Kit Description List (PDF)

PARASITE KIT DESCRIPTION PARASITES 1. Acanthamoeba 39. Diphyllobothrium 77. Isospora 115. Pneumocystis 2. Acanthocephala 40. Dipylidium 78. Isthmiophora 116. Procerovum 3. Acanthoparyphium 41. Dirofilaria 79. Leishmania 117. Prosthodendrium 4. Amoeba 42. Dracunculus 80. Linguatula 118. Pseudoterranova 5. Ancylostoma 43. Echinochasmus 81. Loa Loa 119. Pygidiopsis 6. Angiostrongylus 44. Echinococcus 82. Mansonella 120. Raillietina 7. Anisakis 45. Echinoparyphium 83. Mesocestoides 121. Retortamonas 8. Armillifer 46. Echinostoma 84. Metagonimus 122. Sappinia 9. Artyfechinostomum 47. Eimeria 85. Metastrongylus 123. Sarcocystis 10. Ascaris 48. Encephalitozoon 86. Microphallus 124. Schistosoma 11. Babesia 49. Endolimax 87. Microsporidia 1 125. Spirometra 12. Balamuthia 50. Entamoeba 88. Microsporidia 2 126. Stellantchasmus 13. Balantidium 51. Enterobius 89. Multiceps 127. Stephanurus 14. Baylisascaris 52. Enteromonas 90. Naegleria 128. Stictodora 15. Bertiella 53. Episthmium 91. Nanophyetus 129. Strongyloides 16. Besnoitia 54. Euparyphium 92. Necator 130. Syngamus 17. Blastocystis 55. Eustrongylides 93. Neodiplostomum 131. Taenia 18. Brugia.M 56. Fasciola 94. Neoparamoeba 132. Ternidens 19. Brugia.T 57. Fascioloides 95. Neospora 133. Theileria 20. Capillaria 58. Fasciolopsis 96. Nosema 134. Thelazia 21. Centrocestus 59. Fischoederius 97. Oesophagostmum 135. Toxocara 22. Chilomastix 60. Gastrodiscoides 98. Onchocerca 136. Toxoplasma 23. Clinostomum 61. Gastrothylax 99. Opisthorchis 137. Trachipleistophora 24. Clonorchis 62. Giardia 100. Orientobilharzia 138. Trichinella 25. Cochliopodium 63. Gnathostoma 101. Paragonimus 139. Trichobilharzia 26. Contracaecum 64. Gongylonema 102. Passalurus 140. Trichomonas 27. Cotylurus 65. Gryodactylus 103. Pentatrichormonas 141. Trichostrongylus 28. Cryptosporidium 66. Gymnophalloides 104. Pfiesteria 142. Trichuris 29. Cutaneous l.migrans 67. Haemochus 105. Phagicola 143. Tritrichomonas 30. Cyclocoelinae 68. Haemoproteus 106. Phaneropsolus 144. Trypanosoma 31. Cyclospora 69. Hammondia 107. Phocanema 145. Uncinaria 32. -

Molecular Detection of Human Parasitic Pathogens

MOLECULAR DETECTION OF HUMAN PARASITIC PATHOGENS MOLECULAR DETECTION OF HUMAN PARASITIC PATHOGENS EDITED BY DONGYOU LIU Boca Raton London New York CRC Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 © 2013 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works Version Date: 20120608 International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4398-1243-3 (eBook - PDF) This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any future reprint. Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Law, no part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. For permission to photocopy or use material electronically from this work, please access www.copyright.com (http://www.copyright.com/) or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. -

Studies on the Systematics and Life History of Polymorphous Altmani (Perry)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1967 Studies on the Systematics and Life History of Polymorphous Altmani (Perry). John Edward Karl Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Karl, John Edward Jr, "Studies on the Systematics and Life History of Polymorphous Altmani (Perry)." (1967). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1341. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1341 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67-17,324 KARL, Jr., John Edward, 1928- STUDIES ON THE SYSTEMATICS AND LIFE HISTORY OF POLYMORPHUS ALTMANI (PERRY). Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1967 Zoology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. © John Edward Karl, Jr. 1 9 6 8 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -STUDIES o n t h e systematics a n d LIFE HISTORY OF POLYMQRPHUS ALTMANI (PERRY) A Dissertation 'Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Zoology and Physiology by John Edward Karl, Jr, Mo S«t University of Kentucky, 1953 August, 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Characterization of Terrelysin, a Potential Biomarker for Aspergillus Terreus

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2012 Characterization of terrelysin, a potential biomarker for Aspergillus terreus Ajay Padmaj Nayak West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Nayak, Ajay Padmaj, "Characterization of terrelysin, a potential biomarker for Aspergillus terreus" (2012). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3598. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3598 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Characterization of terrelysin, a potential biomarker for Aspergillus terreus Ajay Padmaj Nayak Dissertation submitted to the School of Medicine at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Immunology and Microbial Pathogenesis Donald H. Beezhold, -

Carbamazepine, Triclocarban and Triclosan Biodegradation and the Phylotypes and Functional Genes Associated with Xenobiotic Degr

Carbamazepine, Triclocarban and Triclosan Biodegradation and the Phylotypes and Functional Genes Associated with Xenobiotic Degradation in Four Agricultural Soils Jean-Rene Thelusmond, Timothy J. Strathmann and Alison M. Cupples Highlights • Rapid triclosan, yet slow carbamazepine & triclocarban degradation • Soils contained genera from previously reported CBZ, TCC or TCS degrading isolates • Several functional genes were enriched in the PPCP amended samples • Bradyrhizobium & Rhodopseudomonas were linked to xenobiotic degradation pathways 1 Carbamazepine, Triclocarban and Triclosan Biodegradation and the Phylotypes and 2 Functional Genes Associated with Xenobiotic Degradation in Four Agricultural Soils 3 Jean-Rene Thelusmond, Timothy J. Strathmann and Alison M. Cupples 4 Abstract 5 Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) are released into the environment due to 6 their poor removal during wastewater treatment. Agricultural soils subject to irrigation with 7 wastewater effluent and biosolids application are possible reservoirs for these chemicals. This 8 study examined the impact of the pharmaceutical carbamazepine (CBZ), and the antimicrobial 9 agents triclocarban (TCC) and triclosan (TCS) on four soil microbial communities using shotgun 10 sequencing (HiSeq Illumina) with the overall aim of determining possible degraders as well as 11 the functional genes related to general xenobiotic degradation. The biodegradation of CBZ and 12 TCC was slow, with ≤ 50 % decrease during the 80-day incubation period. In contrast, TCS 13 biodegradation -

Bacterial Diversity and Functional Analysis of Severe Early Childhood

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Bacterial diversity and functional analysis of severe early childhood caries and recurrence in India Balakrishnan Kalpana1,3, Puniethaa Prabhu3, Ashaq Hussain Bhat3, Arunsaikiran Senthilkumar3, Raj Pranap Arun1, Sharath Asokan4, Sachin S. Gunthe2 & Rama S. Verma1,5* Dental caries is the most prevalent oral disease afecting nearly 70% of children in India and elsewhere. Micro-ecological niche based acidifcation due to dysbiosis in oral microbiome are crucial for caries onset and progression. Here we report the tooth bacteriome diversity compared in Indian children with caries free (CF), severe early childhood caries (SC) and recurrent caries (RC). High quality V3–V4 amplicon sequencing revealed that SC exhibited high bacterial diversity with unique combination and interrelationship. Gracillibacteria_GN02 and TM7 were unique in CF and SC respectively, while Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria were signifcantly high in RC. Interestingly, we found Streptococcus oralis subsp. tigurinus clade 071 in all groups with signifcant abundance in SC and RC. Positive correlation between low and high abundant bacteria as well as with TCS, PTS and ABC transporters were seen from co-occurrence network analysis. This could lead to persistence of SC niche resulting in RC. Comparative in vitro assessment of bioflm formation showed that the standard culture of S. oralis and its phylogenetically similar clinical isolates showed profound bioflm formation and augmented the growth and enhanced bioflm formation in S. mutans in both dual and multispecies cultures. Interaction among more than 700 species of microbiota under diferent micro-ecological niches of the human oral cavity1,2 acts as a primary defense against various pathogens. Tis has been observed to play a signifcant role in child’s oral and general health. -

Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis, a Rare and Under-Diagnosed Fungal Infection in Immunocompetent Hosts: a Review Article

IJMS Vol 40, No 2, March 2015 Review Article Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis, a Rare and Under-diagnosed Fungal Infection in Immunocompetent Hosts: A Review Article Bita Geramizadeh1,2, MD; Mina Abstract 2 2 Heidari , MD; Golsa Shekarkhar , MD Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis (GIB) is an unusual, rare, but emerging fungal infection in the stomach, small intestine, colon, and liver. It has been rarely reported in the English literature and most of the reported cases have been from US, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iran. In the last five years, 17 cases have been reported from one or two provinces in Iran, and it seems that it has been undiagnosed or probably unnoticed in other parts of the country. This article has Continuous In this review, we explored the English literature from 1964 Medical Education (CME) through 2013 via PubMed, Google, and Google scholar using the credit for Iranian physicians following search keywords: and paramedics. They may 1) Basidiobolomycosis earn CME credit by reading 2) Basidiobolus ranarum this article and answering the 3) Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis questions on page 190. In this review, we attempted to collect all clinical, pathological, and radiological findings of the presenting patients; complemented with previous experiences regarding the treatment and prognosis of the GIB. Since 1964, only 71 cases have been reported, which will be fully described in terms of clinical presentations, methods of diagnosis and treatment as well as prognosis and follow up. Please cite this article as: Geramizadeh B, Heidari M, Shekarkhar G. Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis, a Rare and Under-diagnosed Fungal Infection in Immunocompetent Hosts: A Review Article. Iran J Med Sci. -

Fish Mycobacteriosis: Review

Global Veterinaria 21 (6): 337-347, 2019 ISSN 1992-6197 © IDOSI Publications, 2019 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.gv.2019.337.347 Fish Mycobacteriosis: Review Workneh Tesemma, Migbaru Keffale and Simegnew Adugna College of Veterinary Medicine, Haramaya University, P.O. Box: 138, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia Abstract: Fish mycobacteriosis is a chronic disease caused by a group of bacteria (simple single-celled organisms) known as mycobacteria, which affects both in culture and wild setting fishes. It includes both slowly and rapidly growing mycobacterial species that includes M. marinum and M. fortuitum. These two mycobacterial species also have a significant public health impact among human beings. Transmission to human beings includes during handling of fish that is infected by mycobacteria and during cleaning of aquiram and materials already contaminated by fish that have been infected by mycobacteriosis. External clinical sign is rare but it forms a granulomatous lesion on kidney, liver and spleen during post mortem diagnosis. Fish that are infected by mycobacteriosis can’t fit for human consumption and this in turn decreases trade on fish which leads to economic loss in farms. Laboratory confirmation of mycobacteriosis is based on acid-fast microscopy of suspected pathological material. There is no widely accepted treatment for it rather than depopulation which cause a large economic loss in fish farms and facility disinfection as control and protection methods. Key words: Economic Loss Fishes Fish Mycobacteriosis Public Health Impact INTRODUCTION Mycobacteriosis affects a wide range of fresh water and marine fish species, suggesting a ubiquitous Fish mycobacteriosis is known as piscine distribution and has the potential to profoundly impact tuberculosis, which is a chronic progressive disease the fishery sector as a whole and its economic caused by several species of the genus mycobacterium consequences include mortality, morbidity and effects of [1].