The Relationship Between Moss Growth and Treefall Gaps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Supramolecular Organization of Self-Assembling Chlorosomal Bacteriochlorophyll C, D,Ore Mimics

The supramolecular organization of self-assembling chlorosomal bacteriochlorophyll c, d,ore mimics Tobias Jochum*†, Chilla Malla Reddy†‡, Andreas Eichho¨ fer‡, Gernot Buth*, Je¸drzej Szmytkowski§¶, Heinz Kalt§¶, David Moss*, and Teodor Silviu Balaban‡¶ʈ *Institute for Synchrotron Radiation, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe, Postfach 3640, D-76021 Karlsruhe, Germany; ‡Institute for Nanotechnology, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe, Postfach 3640, D-76021 Karlsruhe, Germany; §Institute of Applied Physics, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Universita¨t Karlsruhe (TH), D-76131 Karslruhe, Germany; and ¶Center for Functional Nanostructures, Universita¨t Karlsruhe (TH), D-76131 Karslruhe, Germany Edited by James R. Norris, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and accepted by the Editorial Board July 18, 2008 (received for review March 22, 2008) Bacteriochlorophylls (BChls) c, d, and e are the main light-harvesting direct structural evidence from x-ray single crystal structures, the pigments of green photosynthetic bacteria that self-assemble into exact nature of BChl superstructures remain elusive and these nanostructures within the chlorosomes forming the most efficient have been controversially discussed in the literature (1–3, 7, antennas of photosynthetic organisms. All previous models of the 11–17). It is now generally accepted that the main feature of chlorosomal antennae, which are quite controversially discussed chlorosomes is the self-assembly of BChls and that these pig- because no single crystals could be grown so far from these or- ments are not bound by a rigid protein matrix as is the case of ganelles, involve a strong hydrogen-bonding interaction between the other, well characterized light-harvesting systems (1). Small- 31 hydroxyl group and the 131 carbonyl group. -

Cycad Forensics: Tracing the Origin of Poached Cycads Using Stable Isotopes, Trace Element Concentrations and Radiocarbon Dating Techniques

Cycad forensics: Tracing the origin of poached cycads using stable isotopes, trace element concentrations and radiocarbon dating techniques by Kirsten Retief Supervisors: Dr Adam West (UCT) and Ms Michele Pfab (SANBI) Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Conservation Biology 5 June 2013 Percy FitzPatrick Institution of African Ornithology, UniversityDepartment of Biologicalof Cape Sciences Town University of Cape Town, Rondebosch Cape Town South Africa 7701 i The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Plagiarism declaration iv Abstract v Chapter 1: Status of cycads and background to developing a forensic technique 1 1. Why are cycads threatened? 2 2. Importance of cycads 4 3. Current conservation strategies 5 4. Stable isotopes in forensic science 7 5. Trace element concentrations 15 6. Principles for using isotopes as a tracer 15 7. Radiocarbon dating 16 8. Cycad life history, anatomy and age of tissues 18 9. Recapitulation 22 Chapter 2: Applying stable isotope and radiocarbon dating techniques to cycads 23 1. Introduction 24 2. Methods 26 2.1 Sampling selection and sites 26 2.2 Sampling techniques 30 2.3 Processing samples 35 2.4 Cellulose extraction 37 2.5 Oxygen and sulphur stable isotopes 37 2.6 CarbonUniversity and nitrogen stable of isotopes Cape Town 38 2.7 Strontium, lead and elemental concentration analysis 39 2.8 Radiocarbon dating 41 2.9 Data analysis 42 3. -

Part IX – Appendices

Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary – Proposed Action Plans Part IX – Appendices Monterey Bay Sanctuary Advisory Council Membership List of Acronyms 445 Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary – Proposed Action Plans Appendix 1 – Sanctuary Advisory Council Membership Non-Governmental Members ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Agriculture (Primary & SAC Vice Chair) Mr. Richard Nutter [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Agriculture (Alternate) Mr. Kirk Schmidt Quail Mountain Herbs 831-722-8456 [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Business/Industry (Primary) Mr. Dave Ebert, Ph.D. Project Manager, Pacific Shark Research Center 831-771-4427 [email protected] or [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Business/Industry (Alternate) Mr. Tony Warman 831-462-4059 [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Conservation (Primary) Ms. Vicki Nichols Director of Research & Policy Save Our Shores 831-462-5660 [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Conservation (Alternate) Ms. Kaitilin Gaffney Central Coast Program Director The Ocean Conservancy 831-425-1363 [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Diving (Primary) Mr. Frank Degnan CSUMB [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

Seedless Plants Key Concept Seedless Plants Do Not Produce Seeds 2 but Are Well Adapted for Reproduction and Survival

Seedless Plants Key Concept Seedless plants do not produce seeds 2 but are well adapted for reproduction and survival. What You Will Learn When you think of plants, you probably think of plants, • Nonvascular plants do not have such as trees and flowers, that make seeds. But two groups of specialized vascular tissues. plants don’t make seeds. The two groups of seedless plants are • Seedless vascular plants have specialized vascular tissues. nonvascular plants and seedless vascular plants. • Seedless plants reproduce sexually and asexually, but they need water Nonvascular Plants to reproduce. Mosses, liverworts, and hornworts do not have vascular • Seedless plants have two stages tissue to transport water and nutrients. Each cell of the plant in their life cycle. must get water from the environment or from a nearby cell. So, Why It Matters nonvascular plants usually live in places that are damp. Also, Seedless plants play many roles in nonvascular plants are small. They grow on soil, the bark of the environment, including helping to form soil and preventing erosion. trees, and rocks. Mosses, liverworts, and hornworts don’t have true stems, roots, or leaves. They do, however, have structures Vocabulary that carry out the activities of stems, roots, and leaves. • rhizoid • rhizome Mosses Large groups of mosses cover soil or rocks with a mat of Graphic Organizer In your Science tiny green plants. Mosses have leafy stalks and rhizoids. A Journal, create a Venn Diagram that rhizoid is a rootlike structure that holds nonvascular plants in compares vascular plants and nonvas- place. Rhizoids help the plants get water and nutrients. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

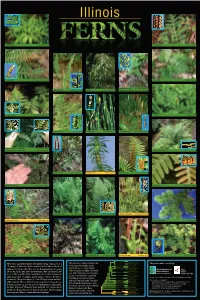

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Lingua Botanica the National Newsletter for FS Botanists & Plant Ecologists

Lingua Botanica The National Newsletter for FS Botanists & Plant Ecologists Many of you are laboring under a common mistaken belief and I’m going to clear this up once and for all. As a botanist for a major land management agency, you stand on the front lines of the battle for plant conservation. You are heavily armed with Federal law, regulation, and public opinion and you have more power than you can imagine to cultivate a future of botanical diversity on the lands of the people of the United States. But I’ve heard many botanists (and wildlife and fisheries biologists) talk about the importance of strong standards and guides in land management plans, planning rule language, strict NEPA compliance, and the utility of outside litigation in the fight to protect rare plants and their habitats. The mistake we too often make is to assume that the battle is won by the sword. This is a serious misconception. Just as Excalibur could not save Arthur and Beowulf died holding the broken hilt of Naegling, no blade, neither enchanted nor sacred, can by itself rend victory from darkness. No. No legal mumbo-jumbo, no order from a court, no legislative edict can assure the viability of a rare plant (or fish or critter) population. Don’t get me wrong, these things can be very helpful, but each of these weapons will fail, at some point, regardless of who is swinging them. But fear not, there is an answer. There is an answer that will guarantee that the resources to which we are dedicated are protected in perpetuity. -

Bernays Moss June 08.Doc [email protected] Moss Of

Bernays Moss June 08.doc [email protected] Moss Of Moisture and Moss On the lone mountain I meet no one, I hear only the echo. At an angle the sun’s rays enter the depths of the wood, And shine upon the green moss. Wang Wei 752 My first impression is of impending doom in the old growth forest. I face the small yews and cedars coated with cattail moss, each tree with outstretched arms and a khaki gown with wide sleeves hanging. These ghostly figures, in oversized clothes of moss are the ghouls of the under- story. The hanging mosses in places here are so dense and bunched that they form monsters like great bears in the forest. Then I notice the lumps. The rocks and stumps and logs are thickly coated in greens and browns and yellows - a myriad of mosses that hide the angles and round the ridges. What else do these carpets cover? What else is hidden? Branches have fallen, the gaps filled with leaf litter, the whole mass coated with moss. Who lives in there? The still-bare broad-leaved maples are swaddled in yellow moss, their trunks and branches thick with it. The deep fissures in the bark of giant Douglas firs contain gray-green lichen, its little gray-green branchlets bearing red crests, and the thick ridges of bark sport a varied green sward of fine branching moss. The smoother bark of great hemlocks is coated with creeping mosses, green, yellow-green and khaki. Some small maples still in winter mode have rings of moss, lumps of it, hanging like mad hair. -

Ball Moss Tillandsia Recurvata

Ball Moss Tillandsia recurvata Like Spanish moss, ball moss is an epiphyte and belongs to family Bromeliaceae. Ball moss [Tillandsia recurvata (L.) L], or an air plant, is not a true moss but rather is a small flowering plant. It is neither a pathogen nor a parasite. During the past couple of years, ball moss has increas- ingly been colonizing trees and shrubs, including oaks, pines, magnolias, crape myrtles, Bradford pears and others, on the Louisiana State University campus and surrounding areas in Baton Rouge. In addition to trees and shrubs, ball moss can attach itself to fences, electric poles and other physical structures with the help of pseudo-roots. Ball moss uses trees or plants as surfaces to grow on but does not derive any nutrients or water from them. Ball moss is a true plant and can prepare its own food by using water vapors and nutrient from the environment. Extending from Georgia to Arizona and Mexico, ball moss thrives in high humidity and low intensity sunlight environments. Unlike loose, fibrous Spanish moss, ball moss grows in a compact shape of a ball ranging in size from a Figure 1. Young ball moss plant. golf ball to a soccer ball. Ball moss leaves are narrow and grayish-green, with pointed tips that curve outward from the center of the ball. It gets its mosslike appearance from the trichomes present on the leaves. Blue to violet flowers emerge on long central stems during spring. Ball moss spreads to new locations both through wind-dispersed seeds and movement of small vegetative parts of the plant. -

Field Guide to the Moss Genera in New Jersey by Keith Bowman

Field Guide to the Moss Genera in New Jersey With Coefficient of Conservation and Indicator Status Keith Bowman, PhD 10/20/2017 Acknowledgements There are many individuals that have been essential to this project. Dr. Eric Karlin compiled the initial annotated list of New Jersey moss taxa. Second, I would like to recognize the contributions of the many northeastern bryologists that aided in the development of the initial coefficient of conservation values included in this guide including Dr. Richard Andrus, Dr. Barbara Andreas, Dr. Terry O’Brien, Dr. Scott Schuette, and Dr. Sean Robinson. I would also like to acknowledge the valuable photographic contributions from Kathleen S. Walz, Dr. Robert Klips, and Dr. Michael Lüth. Funding for this project was provided by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, Region 2, State Wetlands Protection Development Grant, Section 104(B)(3); CFDA No. 66.461, CD97225809. Recommended Citation: Bowman, Keith. 2017. Field Guide to the Moss Genera in New Jersey With Coefficient of Conservation and Indicator Status. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, New Jersey Forest Service, Office of Natural Lands Management, Trenton, NJ, 08625. Submitted to United States Environmental Protection Agency, Region 2, State Wetlands Protection Development Grant, Section 104(B)(3); CFDA No. 66.461, CD97225809. i Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptions -

1 a Simple and Efficient Method of Germinating Cycad Seeds Bart Schutzman Environmental Horticulture Department, University of F

1 A Simple and Efficient Method of Germinating Cycad Seeds© Bart Schutzman Environmental Horticulture Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611-0670, USA Email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION Cycads, an endangered group of plants from the world’s tropics and subtropics, have been a mysterious and intriguing plant group to botanists since they were first documented more than 200 years ago. The number of described species continues to grow as subtropical and tropical regions are thoroughly explored; the latest count published in the World List of Cycads (q.v.) is 343. Interest in these plants has grown tremendously over the last 20 years, especially since accurate information has become readily available on the internet. The World List of Cycads, the Cycad Pages, the Cycad Society’s Web site, and a number of other groups readily share information and photographs. Many species of cycads are endangered, and both plants and seeds can be both difficult and expensive to obtain. The seeds of several species can be difficult to germinate and keep alive. The purpose of this paper is to explain and recommend the “baggie method” of germination, a technique that already is well-known in palms. It is not a new method for cycads by any means, but too many people are still unfamiliar with its ease and benefits. The method increases germination percentage and survivability of scarce and expensive seed. The information is especially useful to both the nursery industry and hobbyists; it will ultimately reduce the pressure exerted by poaching on indigenous cycad populations by making plants of the species easier to 2 obtain. -

Portulaca Grandiflora1

Fact Sheet FPS-491 October, 1999 Portulaca grandiflora1 Edward F. Gilman, Teresa Howe2 Introduction Moss Rose grows well in hot, dry areas in rock gardens, as an edging plant and when interplanted in bulb beds (Fig. 1). Portulaca grandiflora has a flatter leaf than the nearly cylindrical leaf of the Portulaca oleracea. The plants are decorated with a profusion of brilliant jewel-toned blooms throughout the year in south Florida. Freezing temperatures knock plants to the ground in more northern areas, but self-seeded plants may come up the following year. A sunny growing area and a light soil gives the best growth. The plants are six to nine inches tall and are spaced ten to twelve inches apart to form a tight ground cover several months after planting. The flowers of some varieties close at night and on cloudy days. General Information Scientific name: Portulaca grandiflora Pronunciation: por-too-LAY-kuh gran-diff-FLOR-ruh Common name(s): Purslane, Moss Rose, Rose Moss Family: Portulaceae Plant type: herbaceous Figure 1. Purslane. USDA hardiness zones: all zones (Fig. 2) Planting month for zone 7: Jun; Jul Planting month for zone 8: May; Jun; Jul Planting month for zone 9: May; Sep; Oct Description Planting month for zone 10 and 11: Apr; May; Oct; Nov Height: 0 to .5 feet Origin: not native to North America Spread: 1 to 2 feet Uses: container or above-ground planter; naturalizing; edging; Plant habit: round; spreading hanging basket; cascading down a wall Plant density: moderate Availablity: generally available in many areas within its Growth rate: moderate hardiness range Texture: fine 1.This document is Fact Sheet FPS-491, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

Field Guide to the MONTEREY BAY NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY

Field Guide to the MONTEREY BAY NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY 2 4 8 10 12 Welcome to the Monterey Bay Discover Amazing Wildlife! Kids Pages How’s the Water? Get Out and Do It! National Marine Sanctuary Explore&Enjoy the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary! his guide introduces you to some of the sanctuary’s natural wonders—including spectacular wildlife, unique habitats, cultural resources, and endangered species— Tas well as ways to experience its beauty by foot, boat, bike, or car. Walk along cliffs while pelicans glide past, or cruise the waters by kayak shadowed by curious harbor seals. Dive into towering kelp forests, or join scurrying sandpipers at the water’s edge. least explored ecosystems. If we are to live on this planet in ways that sustain our needs, we must better understand the world’s oceans, and accord them the protection they deserve. Marine sanctuaries are one way to protect the marine environment, ensuring a healthy future for us all. A special place The Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary is the nation’s largest marine protected area (larger than either Yosemite or Yellowstone National Parks), spanning 5,322 square miles (13,727 sq. km) along Central California’s coast from the Marin Headlands south to Cambria. Congress designated the sanctuary Snowy egret in 1992 for its biological richness, unique habitats, Powerful waves are common along sanctuary shores. sensitive and endangered animals, and the presence of What is a National Marine Sanctuary? shipwrecks and other cultural relics. Many uses National marine sanctuaries are our nation’s The sanctuary supports many human uses.