07 Pearce 1767

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gold Coins of England, Arranged and Described

THE GOLD COINS OF ENGLAND. FMOTTIS PIECE. Edward die Coiiiessor. 16 TT^mund, Abp.of Yo Offa . King of Mercia ?.$.&&>. THE GOLD COINS OF ENGLAND AERANGED AND DESCRIBED BEING A SEQUEL TO MR. HAWKINS' SILVER COINS OF ENGLAND, BY HIS GRANDSON KOBEET LLOYD KENYON See p. 15. Principally from the collection in tlie British Museum, and also from coins and information communicated by J. Evans, Esq., President of the Numismatic. Society, and others. LONDON: BERNARD QUARITCH, 15 PICCADILLY MDCCCLXXXIV. : LONDON KV1AN AND <ON, PRINTERS, HART STREET. COVENT r,ARI>E\. 5 rubies, having a cross in the centre, and evidently intended to symbolize the Trinity. The workmanship is pronounced by Mr. Akerman to be doubtless anterior to the 8th century. Three of the coins are blanks, which seems to prove that the whole belonged to a moneyer. Nine are imitations of coins of Licinius, and one of Leo, Emperors of the East, 308 to 324, and 451 to 474, respectively. Five bear the names of French cities, Mettis, Marsallo, Parisius. Thirty- nine are of the seven types described in these pages. The remaining forty-three are of twenty-two different types, and all are in weight and general appearance similar to Merovingian ti-ientes. The average weight is 19*9 grains, and very few individual coins differ much from this. With respect to Abbo, whose name appears on this coin, the Vicomte de Ponton d'Ainecourt, who has paid great attention to the Merovingian series, has shown in the " Annuaire de la Societe Francaise de Numismatique " for 1873, that Abbo was a moneyer at Chalon-sur-Saone, pro- bably under Gontran, King of Burgundy, a.d. -

A Short History of Coins and Currency in Two Parts

P R E F A C E T HI S little b ook is founded on an I nt roduc tory A ddres s w hic h I had the hon ou r of delivering s e om e years ago , as fi rst P r s ident of the I nstitute B s o of anker . I t was , however , alm st rewritten last year as a Lectu r e delivered at the London I nstitution . M r Magnus has done me the honou r of sug ges ti ng that it should be i ncluded as one of the i n Hom e a n d Sei wal L ib rar volu mes the y , which n M r M he is ed iti g for urray,“ 2 3 ' i ” The a1 t i i s ) c w T I t d s w second p f . eal ith the w eights of coins ; the adopted ; the means taken from t i me s ecure a satis n d I f e to factory currency ; a , r gret add , those - also perhaps even more numerous — m b y which Kings and Parliaments have attempted to secu re a temporary and dishonou rable advantage , by debasing the standard and reducing the weight of the coins . I n this respect we may f airly clai m that ou r own Sovereigns and Parl iament are able to show V i PRE F A CE (w ith a few exceptio n s) an u n usually honourable c re ord . I n spite of all that has been written on the ' s u b ec t th e u j , principles on which our c rrency is based are very l ittle understood . -

Perth Numismatic Journal

Volume 52 Number 3 August 2020 Perth Numismatic Journal Official publication of the Perth Numismatic Society Inc VICE-PATRON Prof. John Melville-Jones EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: 2019-2020 PRESIDENT Prof. Walter Bloom FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT Ben Selentin SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT Dick Pot TREASURER Alan Peel ASSISTANT TREASURER Sandy Shailes SECRETARY Prof. Walter Bloom MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Sandra Vowles MINUTES SECRETARY Ray Peel FELLOWSHIP OFFICER Jim Selby EVENTS COORDINATOR Prof. Walter Bloom ORDINARY MEMBERS Jim Hidden Jonathan de Hadleigh Miles Goldingham Tom Kemeny JOURNAL EDITOR John McDonald JOURNAL SUB-EDITOR Mike Beech-Jones OFFICERS AUDITOR Vignesh Raj CATERING Lucie Pot PUBLIC RELATIONS OFFICER Tom Kemeny WEBMASTER Prof. Walter Bloom WAnumismatica website Mark Nemtsas, designer & sponsor The Purple Penny www.wanumismatica.org.au Printed by Uniprint First Floor, Commercial Building, Guild Village (Hackett Drive entrance 2), The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, Western Australia 6009 Perth Numismatic Journal Vol. 52 No. 3 August 2020 CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE PERTH NUMISMATIC JOURNAL Contributions on any aspect of numismatics are welcomed but will be subject to editing. All rights are held by the author(s), and views expressed in the contributions are not necessarily those of the Society or the Editor. Please address all contributions to the journal, comments and general correspondence to: PERTH NUMISMATIC SOCIETY Inc PO BOX 259, FREMANTLE WA 6959 www.pns.org.au Registered Australia Post, Publ. PP 634775/0045, Cat B WAnumismatica website: www.wanumismatica.org.au Designer & sponsor: Mark Nemtsas, The Purple Penny Perth Numismatic Journal Vol. 52 No. 3 August 2020 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH PENNY PART I - FROM OFFA TO EDWARD THE CONFESSOR John Wheatley Introduction The history of the simple English penny is not just a reflection of the social and economic history of England; it is about the metals used to produce those coins (gold, silver, copper and bronze) and about the richness of the designs and craftsmanship. -

Anglo-Norman Money Names in Context

94 kalbų studijos / studies about languages no. 32 / 2018 SAL 32/2018 Anglo-Norman Money Anglo-Norman Money Names in Names in Context Context Received 12/2017 Anglų-normanų pinigų Accepted 05/2018 pavadinimai kontekste SOCIOLINGUISTICS / SOCIOLINGVISTIKA Natalya Davidko PhD, associated professor, Moscow Institute Touro (MIT), Russia. http://dx.doi.org/10.5755/j01.sal.0.32.19597 The present study is the second in a series of inquiries into the specificity of money names in the history of English. The time frame is the Anglo-Norman period (1066–1500). The paper explores two distinct concepts – that of money as an abstract ideal construct and the concept of the coin represented by sets of nummular tokens. The centrality of cognitive concepts allows us to establish a link between socio-historical factors and actuation of naming, i. e., to study medieval onomasiological patterns in all complexity of social, cognitive, political, and ideological aspects. Semiotic study of Anglo-Norman coinage gives an insight into the meaning of messages Kings of England and France tried to communicate to each other and their subjects through coin iconography employing a set of elaborate images based on culturally preferred symbolic elements. By studying references to medieval coinage in various literary genres, we propose to outline some of the contours of new metaphoricity based on the concept of money and new mercantile ideology. KEYWORDS: Anglo-Norman, trilingualism, culture, cognitive narratology, onomasiological patterns, money symbolism, semiotics, concept of the coin, mercantile ideology. On earth there is a little thing, Sir Penny is his name, we’re told, That reigns as does the richest king He compels both young and old In this and every land; To bow unto his hand. -

CATALOGUE of the SCOTTISH COINS Belonging to the SOCIETY of ANTIQUA- RIES of SCOTLAND, Arranged in Chronological Order :—

APPENDIX. CATALOGUE of the SCOTTISH COINS belonging to the SOCIETY of ANTIQUA- RIES of SCOTLAND, arranged in Chronological Order :— No. King. Value. DKAWER 1. Size. Weight. 1. Alexander I. Penny Silver. King's head, regarding the left, with a sceptre, ALEX- D 1107. ADER. REX. R. A cross double parted anchoree, with four stars of six points in the angles -f- W . ER ON BER: Rare. (Supposed to be the first Scottish coin.) 2. 3. • 1. David I. Penny Silver. 1124. 2. 3. APPENDIX. 9 APPENDIX. No. King. Value. DRAWER I. Size. Weight. 1. Alexander III. Penny Silver. King's head crowned, regarding the right, with a E No. King. Value. DRAWER I. Weight. 1249. sceptre, surmounted by a flew de Us. Inscr. Penny Silver. E William the King's head regarding the right, crown with three ALEXADER DEI GRA; a very youthful face. Lyon. 116*. fours de Us, a sceptre, surmounted with four parts R. Cross anchoree extending through the legend, a in cross, behind the head, a crescent embracing a pel- spur revel of six points in the quarters. SCOTO- let, all inclosed within a dotted circle. Inscr. LE. RVM REX. REI WILAM. Do. Very similar to the last, with the exception of two stars E El. Cross anchoree, crescent with two pellets at the and two spur revels on the reverse. angles, inclosed with a circle of pearls. Inscr. 3. Do. Small variation on the reverse in the number of points E ADAM ON EDENBV. to the stars. 2. Do. LE REI WILLAM, as No. 1, with two crescents 4. -

Treasure Act Annual Report 2018

Treasure Act Annual Report 2018 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 12 of the Treasure Act 1996 March 2021 ii Treasure Act Annual Report 2018 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 12 of the Treasure Act 1996 March 2021 1 © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021 Compiled by I Richardson Published by Portable Antiquities and Treasure, Learning and National Partnerships, British Museum 2 Contents Minister’s foreword 5 Introduction 6-7 Statistical highlights from Treasure cases 2018 8-21 Table of Treasure cases 2018 22 3 4 Minister’s Foreword It is a great pleasure to introduce this year’s Treasure Act 1996 Annual Report, which gives an overview of how the Treasure Act operated in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2018. The Treasure Act relies on the time and expertise of many people across the country, including Finds Liaison Officers, funding partners and museum teams, who all deserve huge thanks for their hard work and contributions to the process. Finders and landowners are also at the heart of the Treasure Act and it’s brilliant to see 76 finders and landowners who donated their finds in 2018. I’d like to thank the Treasure Registry at the British Museum, the Amgueddfa Cymru/National Museum of Wales and the Department of Environment and Ulster Museum in Northern Ireland for their continued work to support the delivery of the Treasure Act across the UK. The Treasure Valuation Committee has also provided more expert advice this year, and I welcome their new chair, Roger Bland, who brings his formidable knowledge and expertise to the role. -

MEDIEVAL COINS – an Introduction

MEDIEVAL COINS – An Introduction Richard Kelleher, Fitzwilliam Museum and Barrie Cook, British Museum PART 1. BACKGROUND 1) Early coinage (c.600-860s) This early phase saw the emergence of a gold coinage on a small scale inspired by imported Merovingian coins. Over the 7 th century the gold gave way to a much more extensive silver currency Shilling/Tremissis/‘Thrymsa’ (early 7 th century) The first indigenous English coins imitated Frankish tremisses with occasional Roman or Byzantine influences. They are often referred to as ‘thrymsas’ but there is no evidence for the use of this word in the period. They were struck in Kent and London and (probably) York. Weight: c.1.28g Diameter: 12mm Metal: Gold Design: various but often an obverse bust and some form of reverse cross. A few have inscriptions. As UK finds: Extremely rare. Penny/Sceat/‘Sceatta’ (c.660-mid 8 th century) After a transitional phase comprising base gold coins the silver penny emerged c.660-680. These small, thick coins were of a similar size to the gold shillings. The use of the name ‘sceatta’ which one often sees was not a contemporary term. Weight: c.1.10g Diameter: 12mm Metal: Silver Design: Huge variety in imagery including busts, crosses, plants, birds and animals. As UK finds: Common. Penny/‘Styca’ Coinage in the kingdom of Northumbria developed differently to that elsewhere in the late 8 th and 9 th centuries. The silver pennies became debased until they were essentially copper. They were produced in large quantities. Weight: c.1.2g Diameter: mm Metal: Copper Design: Inscription around a central pellet or cross, naming the ruler and moneyer. -

O Copyright Martin A. Armstrong All Rights Reserved ^ Comments

h4 CO c o -H 4J ca: c 5-t CD •4-1 a i—i tt u •H 1 c o o c' • o J-l CD Q C •H S- p l 00 e y-i o o M 4-1 C u i¬ CO P < O § CO C Copyright Martin A. Armstrong All Rights Reserved ^ Comments Welcome; [email protected] (Internationally) FOK. FASTEfZ. RBftWSG ^N(S cettt'RFO MAIL ' do it '? May 1st, 2009 by: Martin A. Armstrong former Chairman of Princeton Economics International, Ltd. and Foundation for the Study of Cycles There is no doubt we will see a new Cne World Currency. This is the next step in the evolution process of Okinomikos (Economics) as Xenophon (431-352BC ca) first coined the word as the title to his book that today probably would have been given the illustrious title - How to manage your estate including your wife and slaves - for Dummies! (meaning = how to regulate the household). Until 1971, the world for the most part, relied upon gold as money. It was the neutral store of wealth that was recognized around the world. There were times when the gold standard was suspended, such as during the American Civil War. And there were times when some countries adopted a silver standard because they had too little gold to create a viable money supply domestically such as in China and Mexico during the last quarter-century in the 1800s. There was a suspension of the gold standard during periods of war, but we must exclude these interregnum periods for now. -

Proceedings of the British Numismatic Society, 1948

PROCEEDINGS OF THE BRITISH NUMISMATIC SOCIETY, 1948 [For list of past Presidents and Medallists see p. 80; the Officers and Council for 1948 show the following changes from 1947 (p• 99): Director, Mr. C. A. Whitton; Librarian, Mr. D. Mangakis; Council, Messrs. G. V. Doubleday, W. Hurley, C. W. Peck, and P. H. Sellwood vice Messrs. J. Davidson, D. Mangakis, C. A. Whitton, and the late J. B. Caldecott.) ORDINARY MEETING 28 JANUARY 1948 MR. c. E. BLUNT, President, in the Chair The following were nominated for election to membership of the Society: Mr. George R. Blake, "Adanac", Crabwood Road, Millbrook, Southampton. Rev. J. W. Clarke, B.A., C.F., Gormanston, Meath, Eire. Mr. E. Wesander, 16 Lawn Road, London, N.W. 3. Messrs. H. Horsman, Doran A. Jones, D. Elliott Smith, and Sydney V. Hagley were elected Members of the Society. Mr. L. A. Lawrence, F.R.C.S., was elected an Honorary Member of the Society. Exhibitions By the PRESIDENT on behalf of MR. D. F. ALLEN: 1. Edward the Confessor: a cast of a penny of Warwick, moneyer Lyfinc; same type and moneyer as Mr. Lockett's gold penny. 2. A cast of the gold penny; the original was exhibited separately. By MR. ALBERT BALDWIN." A Short-cross penny of Henry II of Oxford type 16, reading ROD6T • K • B • ON • OXON. Apparently unpublished with this surname. By MR. LINECAR on behalf of MESSRS. SPINK: A Charles I "Ormonde" shilling, struck on a flan cut from a piece of plate, still showing the hall-mark, a lion passant, and the letter R. -

Additions and Corrections to Thompson's Inventory and Brown and Dolley's Coin Hoards - Part 1

ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO THOMPSON'S INVENTORY AND BROWN AND DOLLEY'S COIN HOARDS - PART 1 H.E. MANVILLE ALL who work with post-Roman British coin hoards and finds should be familiar with Thompson's Inventory1 and Brown and Dolley's Coin Hoards.2 The material is presented quite differently in these compilations and although both are extremely valuable resources, the first was published almost forty years ago, the second more than twenty. Quite naturally many additions and corrections can be made to each in light of new or newly-uncovered reports. Thompson's pioneering work often has been criticized for its many shortcomings.3 The work omits and/or misinterprets much easily-obtainable data and contains a number of careless errors which a good editor should have corrected. Nevertheless he performed a valuable service in drawing together material from many sources and it remains a useful starting point for further research. Thompson himself provided a 'recension' after criticism of the archaeological content4-5 and listed two pairs of hoards that had come to his attention since publication - to which I have taken the liberty of assigning numbers: *35a. BATH, Abbey/Priory House, 1755 (A) Tenth-century pennies (eighth/ninth-century? sceattae). Ref: Metcalf, NC 6, 18 (1958), 77-9; Lewis, Topographical Dictionary of England 1 (1845), 169. *35b. BATH , Abbey/Priory House, 1755 (B) 50 Anglo-Saxon pennies of Aelfred-Eadred. Deposit c. 955. Ref: Metcalf, op. cit.; Lucy, Essay on Waters 3, 224. *361a. TREDINGTON, Warks, 1. c. 1914-30? Deposit: After 1471. About 40 silver coins of Edward I-IV . -

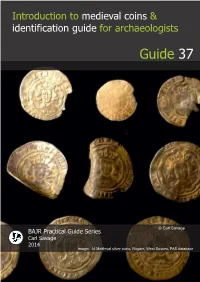

Medieval Coins and ID Guide

Introduction to medieval coins & identification guide for archaeologists Guide 37 © Carl Savage BAJR Practical Guide Series Carl Savage 2014 image: 14 Medieval silver coins, Rogate, West Sussex, PAS database Introduction to medieval coins and identification guide for archaeologists Carl Savage Carl Savage is a freelance medieval and post medieval numismatist based in Carlisle. He is responsible for the identification of medieval and post medieval coinage for the Portable Antiquities Scheme in Lancashire and Cumbria and is also the numismatic consultant to several archaeological companies in the UK. He has also worked in commercial archaeology on various sites and is an accredited member of the IFA. For enquires email [email protected] 1 Contents Page 3: Introduction and numismatic terminology Page 4: Basic medieval coin layout and reading the legends Page 7: Denominations Page 10: Part II coin classifications: Introduction and the Norman coins 1066-1158 Page 14: Cross-crosslets coinage 1158-1180 Page 15: The short cross coinage 1180-1247 Page 18: The voided long cross coinage 1247-79 Page 20: Long cross coinage Edward I and II 1279-1327 Page 22: Long cross coinage Edward III and Richard II 1327-99 Page 27: Long cross coinage Henry IV, V and VI 1399-1461 Page 31: The long cross coinage Edward IV, V and Richard III 1461-85 Page 33: The early Tudor coinage Henry VII and VIII 1485-1544 Page 35: Scottish and Irish coins Page 38: Bibliography 2 Introduction Today coins are mostly found by metal detectorists but occasionally they are found on archaeological sites. This guide will offer a basic and easy to use identification guide for the main types of English medieval coins dating from 1066-1544. -

Quarter-Sovereigns and Other Small Gold Patterns of the Mid-Victorian Period

QUARTER-SOVEREIGNS AND OTHER SMALL GOLD PATTERNS OF THE MID-VICTORIAN PERIOD G. P. DYER FROM the introduction of the guinea in 1663 to the demise of the circulating gold sovereign during the First World War, a certain continuity of structure is evident in the broad sweep of the milled gold coinage. Leaving aside the international role of British gold coins, what we see in essence is a domestic circulation made up at first very largely of guineas and half-guineas, and then, from 1817, of the corresponding sovereigns and half-sovereigns. Throughout this long period of 250 years there was little use for gold coins of higher value; two-guinea and five-guinea pieces, for instance, were minted with increasing irregularity and died away completely after 1753, while two-pound and five-pound pieces later played so small and infrequent a part that in 1893 they could be regarded as hardly more than ornaments. At the other end of the scale, for gold coins below a half-guinea or a half-sovereign in value, there was apparently a similar lack of enthusiasm on the part of the British public. It is at this lower end of the denominational range that my paper is directed, for what I want to do is to explain how it was that, against this discouraging background, misguided notions of issuing small gold coins should have built up a head of steam in the 1850s and 1860s before being rightly and sensibly derailed. First, of course, let me acknowledge that small gold coins had not been entirely absent, for quarter-guineas had been struck in 1718 and 1762 and there had been issues of third-guineas, or seven-shilling pieces, between 1797 and 1813.