Muzeológia Museology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of the Orchids of the Crimea (Orchidaceae)

J. Eur. Orch. 46 (2): 407 - 436. 2014. Alexander V. Fateryga and Karel C.A.J. Kreutz Checklist of the orchids of the Crimea (Orchidaceae) Keywords Orchidaceae, checklist of species, new nomenclature combinations, hybrids, flora of the Crimea. Summary Fateryga, A.V. & C.A.J. Kreutz (2014): Checklist of the orchids of the Crimea (Orchidaceae).- J. Eur. Orch. 46 (2): 407-436. A new nomenclature checklist of the Crimean orchids with 49 taxa and 16 hybrids is proposed. Six new taxa are added and ten taxa are excluded from the latest checklist of the Crimean vascular flora published by YENA (2012). In addition, five nomenclature changes are proposed: Epipactis persica (Soó) Nannf. subsp. taurica (Fateryga & Kreutz) Fateryga & Kreutz comb. et stat. nov., Orchis mascula (L.) L. var. wanjkovii (E. Wulff) Fateryga & Kreutz stat. nov., Anacamptis ×simorrensis (E.G. Camus) H. Kretzschmar, Eccarius & H. Dietr. nothosubsp. ticinensis (Gsell) Fateryga & Kreutz stat. nov., ×Dactylocamptis uechtritziana (Hausskn.) B. Bock ex M. Peregrym & Kuzemko nothosubsp. magyarii (Soó) Fateryga & Kreutz comb. et stat. nov., and Orchis ×beyrichii Kern. nothosubsp. mackaensis (Kreutz) Fateryga & Kreutz comb. et stat. nov. Moreover, a new variety, Limodorum abortivum (L.) Sw. var. viridis Fateryga & Kreutz var. nov. is described. Zusammenfassung Fateryga, A.V. & C.A.J. Kreutz (2014): Eine Übersicht der Orchideen der Krim (Orchidaceae).- J. Eur. Orch. 46 (2): 407-436. Eine neue nomenklatorische Liste der Orchideen der Krim mit 49 Taxa und 16 Hybriden wird vorgestellt. Sechs Arten sind neu für die Krim. Zehn Taxa, die noch bei YENA (2012) in seiner Checklist aufgelistet wurden, kommen auf der Krim nicht vor und wurden gestrichen. -

Ukraine Civil Society Sectoral Support Activity Semi-Annual Progress Performance Report

Ukraine Civil Society Sectoral Support Activity Semi-Annual Progress Performance Report Ukraine Civil Society Sectoral Support Activity FY 2020 SEMI-ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT (01 October 2020 – 31 March 2021) Award No: 72012119CA00003 Prepared for USAID/Ukraine C/O American Embassy 4 Igor Sikorsky St., Kyiv, Ukraine 04112 Prepared by “Ednannia” (Joining Forces) – The Initiative Center to Support Social Action 72 Velyka Vasylkivska Str., office 8, Kyiv, Ukraine Implemented by the Initiative Center to Support Social Action “Ednannia” (Ednannia hereafter) as a prime implementing partner in a consortium with the Ukrainian Center for Independent Political Research (UCIPR) and the Center for Democracy and Rule of Law (CEDEM). Ukraine Civil Society Sectoral Support Activity FY 2020 SEMI-ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT Table of Contents I. ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................................. 2 II. CONTEXT UPDATE ....................................................................................................................................... 4 III. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................. 5 IV. KEY NARRATIVE ACHIEVEMENT ................................................................................................................. 8 OBJECTIVE 1: STRENGTHEN INSTITUTIONAL CAPACITIES OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS (CSOS) (PRIMARILY IMPLEMENTED BY EDNANNIA) ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Second Contribution to the Vascular Flora of the Sevastopol Area

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Wulfenia Jahr/Year: 2015 Band/Volume: 22 Autor(en)/Author(s): Seregin Alexey P., Yevseyenkow Pavel E., Svirin Sergey A., Fateryga Alexander Artikel/Article: Second contribution to the vascular flora of the Sevastopol area (the Crimea) 33-82 © Landesmuseum für Kärnten; download www.landesmuseum.ktn.gv.at/wulfenia; www.zobodat.at Wulfenia 22 (2015): 33 – 82 Mitteilungen des Kärntner Botanikzentrums Klagenfurt Second contribution to the vascular flora of the Sevastopol area (the Crimea) Alexey P. Seregin, Pavel E. Yevseyenkov, Sergey A. Svirin & Alexander V. Fateryga Summary: We report 323 new vascular plant species for the Sevastopol area, an administrative unit in the south-western Crimea. Records of 204 species are confirmed by herbarium specimens, 60 species have been reported recently in literature and 59 species have been either photographed or recorded in field in 2008 –2014. Seventeen species and nothospecies are new records for the Crimea: Bupleurum veronense, Lemna turionifera, Typha austro-orientalis, Tyrimnus leucographus, × Agrotrigia hajastanica, Arctium × ambiguum, A. × mixtum, Potamogeton × angustifolius, P. × salicifolius (natives and archaeophytes); Bupleurum baldense, Campsis radicans, Clematis orientalis, Corispermum hyssopifolium, Halimodendron halodendron, Sagina apetala, Solidago gigantea, Ulmus pumila (aliens). Recently discovered Calystegia soldanella which was considered to be extinct in the Crimea is the most important confirmation of historical records. The Sevastopol area is one of the most floristically diverse areas of Eastern Europe with 1859 currently known species. Keywords: Crimea, checklist, local flora, taxonomy, new records A checklist of vascular plants recorded in the Sevastopol area was published seven years ago (Seregin 2008). -

Andrzej Koziel

Originalveröffentlichung in: Bulletin du Musée National de Varsovie, 38 (1997), Nr. 1-4, S. 66-92 Andrzej Koziel Michael Willmann - i. e. David Heidenreich. The "Rudolphian" Drawings of Michael Willmann* Throughout the history of the study of drawings by the old masters there have not been many attributive mistakes with such dire consequences the scale of the one committed around the middle of the 18th century by an unknown Wroclaw (Breslau) collector possessing a sizeable collection of drawings left behind by painter Johann Eybelwieser, co-worker of Michael Willmann. In an attempt at that time to separate the works of the master from those of the pupil, characteristic inscriptions (M. Willman, M. Willman fee. or/. Eybelwiser, J. Eybelwiser fee.) put on by the same hand appeared on all the drawings. Although the collector, for the most part, correctly ascribed many of the works to Eybelwiser, he also, however, ascribed to the much more famous Willmann more than 60 works out of which not one turned out to have actually been executed by him.1 This first evident act of Wroclaw connoisseurship set a precedent for the way Willmann's creative style has been viewed, causing future art historians to be faced with the phenomenon which E. Kloss described as "das Reichtum der zeichnerischen Moglichkeiten" of the artist. Among the works ascribed to Willmann by the 18th century Wroclaw collector, those bearing a decidedly Mannerist aspect first gained the attention of art historians. E. Kloss was the first to notice a very close stylistic resemblance between certain works derivatively signed by Willmann and those of Bartholomaeus Spranger. -

An Unknown Source Concerning Esaias Reusner Junior from the Music Collection Department of Wroclaw University Library

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 11,2012 © PTPN& Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, Poznań 2012 GRZEGORZ JOACHIMIAK Department of Musicology, University of Wroclaw An unknown source concerning Esaias Reusner Junior from the Music Collection Department of Wroclaw University Library ABSTRACT: The Music Collection Department of Wroclaw University Library is in possession of an old print that contains the following inscription: ‘Esaias Reusner | furste Brigischer | Lautenist’. This explicitly indicates the lutenist Esaias Reusner junior (1636-1679), who was born in Lwówek Śląski (Ger. Lówenberg). A comparative analysis of the duct of the handwriting in this inscription and in signatures on letters from 1667 and 1668 shows some convergences between the main elements of the script. However, there are also elements that could exclude the possibility that all the autographs were made by the same person. Consequently, it cannot be confirmed or unequivocally refuted that the inscription is an autograph signature of the lutenist to the court in Brzeg (Ger. Brieg). The old print itself contains a great deal of interesting information, which, in the context of Silesian musical culture of the second half of the seventeenth century and biographical information relating to the lutenist, enable us to become better acquainted with the specific character of this region, including the functioning of music in general, and lute music in particular. The print contains a work by Johann Kessel, a composer and organist from Oleśnica (Ger. Ols), who dedicated it to three brothers of the Piast dynasty: Georg III of Brzeg, Ludwig IV of Legnica and Christian of Legnica. It is a ‘Paean to brotherly unity”, which explains the reference to Psalm 133. -

Summer 2020 Features

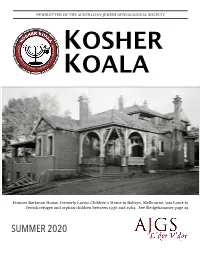

NEWSLETTER OF THE AUSTRALIAN JEWISH GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY KOSHER KOALA Frances Barkman House, formerly Larino Children’s Home in Balwyn, Melbourne, was home to Jewish refugee and orphan children between 1936 and 1964. See Sledgehammer page 19 SUMMER 2020 FEATURES AJGS THANKS EVELYN FRYBORT SUNNY GOLD & JEANNETTE TSOULOS Long-time AJGS committee member Evelyn Frybort has stepped down from the committee. Sunny Gold and Jeannette Tsoulos reflect on her substantial contribution to the AJGS committee. Evelyn Frybort was welcomed onto the AJGS committee in March 2009 and served as a committee member until she resigned in January. The committee accepted her resignation with regret, as her contribution to the Society has been enthusiastic and generous. Evelyn is a longstanding member of AJGS, having joined in July, 1997. Knowing virtually nothing about her family background she began her research in the Society archives with help from Rieke Nash. Trips to her ancestral towns with her sister Vicki Israel followed and they were welcomed by mayors and officials in all the towns they visited. Evelyn gave talks and wrote several articles for the Kosher Koala about her trips and research discoveries. Part of her ancestral area overlapped with Rieke’s, which allowed them to do a lot of work together. They attended the IAJGS conference in Boston in 2013, where Evelyn gave a presentation on her research, and with Rieke, she was involved in setting up a new Special Interest Group (SIG) for the Kolo-Rypin-Plock area, west of Warsaw. Evelyn has kept in touch with International researchers and added material to the Virtual Shtetl Website and the JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry. -

Crimea______9 3.1

CONTENTS Page Page 1. Introduction _____________________________________ 4 6. Transport complex ______________________________ 35 1.1. Brief description of the region ______________________ 4 1.2. Geographical location ____________________________ 5 7. Communications ________________________________ 38 1.3. Historical background ____________________________ 6 1.4. Natural resource potential _________________________ 7 8. Industry _______________________________________ 41 2. Strategic priorities of development __________________ 8 9. Energy sector ___________________________________ 44 3. Economic review 10. Construction sector _____________________________ 46 of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea ________________ 9 3.1. The main indicators of socio-economic development ____ 9 11. Education and science ___________________________ 48 3.2. Budget _______________________________________ 18 3.3. International cooperation _________________________ 20 12. Culture and cultural heritage protection ___________ 50 3.4. Investment activity _____________________________ 21 3.5. Monetary market _______________________________ 22 13. Public health care ______________________________ 52 3.6. Innovation development __________________________ 23 14. Regions of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea _____ 54 4. Health-resort and tourism complex_________________ 24 5. Agro-industrial complex __________________________ 29 5.1. Agriculture ____________________________________ 29 5.2. Food industry __________________________________ 31 5.3. Land resources _________________________________ -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

MB Kupershteyn TOWN of BAR: Jewish Pages Through

1 M. B. Kupershteyn TOWN OF BAR: Jewish Pages Through The Prism Of Time Vinnytsia-2019 2 The publication was carried out with the financial support of the Charity Fund " Christians for Israel-Ukraine” K 92 M. B. Kupershteyn Town of Bar: Jewish Pages Through The Prism Of Time. - Vinnytsia: LLC "Nilan-LTD", 2019 - 344 pages. This book tells about the town of Bar, namely the life of the Jewish population through the prism of historical events. When writing this book archival, historical, memoir, public materials, historical and ethnographic dictionaries, reference books, works of historians, local historians, as well as memories and stories of direct participants, living witnesses of history, photos from the album "Old Bar" and from other sources were used. The book is devoted to the Jewish people of Bar, the history of contacts between ethnic groups, which were imprinted in the people's memory and monuments of material culture, will be of interest to both professionals and a wide range of readers who are not indifferent to the history of the Jewish people and its cultural traditions. Layout and cover design: L. M. Kupershtein Book proofer: A. M. Krentsina ISBN 978-617-7742-19-6 ©Kupers M. B., 2019 ©Nilan-LTD, 2019 3 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 5 HISTORICAL BAR .......................................................................... 7 FROM THE DEPTHS OF HISTORY .................................................. 32 SHTETL .................................................................................... -

Schmertzhaffter Lieb Und Creutz-Weeg... - Krzeszowska Książka Pasyjna Schmertzhaffter Lieb Und Creutz-Weeg

Schmertzhaffter Lieb und Creutz-Weeg... - Krzeszowska książka pasyjna Schmertzhaffter Lieb und Creutz-Weeg... - The Krzeszów Passion Book Schmertzhaffter Lieb und Creutz-Weeg... - Das Grüssauer Passionsbuch Schmertzhaffter Lieb und Creutz-Weeg... - Krzeszowská pašijová kniha 7 Redaguje zespół / editorial staff: Artur Bielecki (konsultant muzyczny / musical consultant) Przemysław Jastrząb (redaktor graficzny / graphics editor) Piotr Karpeta (konsultant muzyczny / musical consultant) Edyta Kotyńska (redaktor naczelna / editor-in-chief) Poszczególne opisy opracowali / descriptions written by: Alicja Borys (AB) Ryszard Len (RL) Małgorzata Turowska (MT) Przekłady na języki obce / translations: Anna Leniart Kateøina Mazáèová Dennis Shilts Korekta: kolektyw autorski / Proof-reading: staff of authors Kopie obiektów wykonali / copies of objects: Pracownia Reprograficzna Biblioteki Uniwersyteckiej we Wrocławiu (Tomasz Kalota, Jerzy Katarzyński, Alicja Liwczycka, Marcin Szala) Nagrane utwory wykonują / recordings performed by: zespół Ars Cantus / the group Ars Cantus (CD 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.9) chór kameralny Cantores Minores Wratislavienses / the Cantores Minores Wratislavienses chamber choir (CD 7.4, 7.5, 7.6, 7.7, 7.8) www.arscantus.art.pl www.cantores.art.pl Skład i druk: Drukarnia i oficyna wydawnicza FORUM nakład 800 egz. ISBN 83-89988-00-3 (całość) ISBN 83-89988-07-0 (vol. 7) © Wrocławscy Kameraliści & Biblioteka Uniwersytecka we Wrocławiu, Wrocław 2005 Wrocławscy Kameraliści Cantores Minores Wratislavienses PL 50-156 Wrocław, ul. Bernardyńska 5, tel./fax + 48 71 3443841, www.cantores.art.pl Biblioteka Uniwersytecka we Wrocławiu PL 50-076 Wrocław, ul. K. Szajnochy 10, tel. + 48 71 3463120, fax +48 71 3463166, www.bu.uni.wroc.pl Wprowadzenie Niniejszy katalog jest rezultatem współpracy bibliotekarzy i muzyków z kilku europejskich ośrodków naukowych oraz jednym z elementów projektu „Bibliotheca Sonans“ dofinansowywanego przez Unię Europejską w ramach programu Kultura 2000. -

Décoloniser La Muséologie Descolonizando La Museología

Decolonising Museology Décoloniser la Muséologie Descolonizando la Museología 2 The Decolonisation of Museology: Museums, Mixing, and Myths of Origin La Décolonisation de la Muséologie : Musées, Métissages et Mythes d’Origine La Descolonización de la Museología: Museos, Mestizajes y Mitos de Origen Editors Yves Bergeron, Michèle Rivet 1 Decolonising Museology Décoloniser la Muséologie Descolonizando la Museología Series Editor / Éditeur de la série / Editor de la Serie: Bruno Brulon Soares 1. A Experiência Museal: Museus, Ação Comunitária e Descolonização La Experiencia Museística: Museos, Acción Comunitaria y Descolonización The Museum Experience: Museums, Community Action and Decolonisation 2. The Decolonisation of Museology: Museums, Mixing, and Myths of Origin La Décolonisation de la Muséologie : Musées, Métissages et Mythes d’Origine La Descolonización de la Museología: Museos, Mestizajes y Mitos de Origen International Committee for Museology – ICOFOM Comité International pour la Muséologie – ICOFOM Comité Internacional para la Museología – ICOFOM Editors / Éditeurs / Editores: Yves Bergeron & Michèle Rivet Editorial Committee / Comité Éditorial / Comité Editorial Marion Bertin, Luciana Menezes de Carvalho President of ICOFOM / Président d’ICOFOM /Presidente del ICOFOM Bruno Brulon Soares Academic committee / Comité scientifique / Comité científico Karen Elizabeth Brown, Bruno Brulon Soares, Anna Leshchenko, Daniel Sch- mitt, Marion Bertin, Lynn Maranda, Yves Bergeron, Yun Shun Susie Chung, Elizabeth Weiser, Supreo Chanda, Luciana