Eyes in the Sky Autonomous Aircraft Take Flight, Mimic Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Tech That, for the First Time Since the Will Report on His Recent Trav Affairs Officer

CaliforniaTech Associated Students of the California Institute of Technology Volume LXII. Pasadena, California, Thurs'day, February 16, 1961 Number 18 ASCIT Elections Next Tuesday Russ, Sallee Annual Rally Hughes Win Set Monday Travel Prizes Tuesday's elections, preceded by the election rally on Monday Junior Travel Prizes for this night, features Bob Koh and year were announced by Dr. Dave Pritchard battling for the Horace Gilbert, Professor of Eco- office of ASCIT President, as nomics. The winners are Evan well as 18 others running for Hughes, Jr., John Russ, and the remaining offices. George Sallee. The winners, were Candidates' statements appear chosen from among 11 complet on pages 4 and 5 of tliis issue. ed applications. The candidates have also been campaigning in the Student Each of the recipients of a Houses and have posters on dis travel prize must select a proj play. ect which they wish to study on their trip. This project, how The nominees are: ever, is not meant to be an all ASCIT President-Bob Koh, encompassing work of art. The Candidates (front row): Bruce, Abell, Dave Benson, Jon Kelly; (second row): Lance Taylor, Jim Dave Pritchard principal purpose of the project Sagawa, Lee Molho, Howard Monell, Pete Metcalf, Jim Geddis; (back row): Art Robinson, Don O'Hara, Vice-President-Dean Gerber is that it serves as an excuse George McBean, John Golden, John Arndt. Secretary-Art Robinson to make contact with other peo Treasurer-Jim Geddis, John ple, making the trip more than Trustees Pick Golden just an average tour. Sallee's Hanna Concludes AUFS Series; Athletic Manager-John Arndt project is a study of the Euro Business Manager-Jim Sagawa pean beet sugar industry, while New Members Activities Chairman-Jon Kelly Russ will study German and To Dicuss Sf Asia Problems Three eastern business execu Social Chairman-Pete Metcalf, British church music and tives have been elected to the Howard Monell BY MATT COUCH senior posts in the U.S. -

Urine Sample Bank

Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine 2251 Dick George Rd., Cave Junction, OR 97523 We are working to bring advanced technology for diagnostic and preventive medicine to the American people. symptoms. It is of great importance to detect breast cancer Medical Break-through at the early in this process, take steps to prevent it, and – if it oc- Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine curs – to monitor it very carefully during medical therapy. It is best to detect breast cancer so early that the increased Scientists at the Oregon Institute of Science and Medi- probability of the disease can be fought therapeutically by cine, a nonprofit research institute, have been working to less invasive means, rather than waiting until disease symp- improve diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive medicine. toms arrive and require severe, less effective treatment. Now, they have made a remarkable break-through. OISM scientists have found metabolic patterns in human As reported in the Fall 2017 issue of the Journal of Ameri- urine that are predictive of developing breast cancer – mea- can Physicians and Surgeons, they have discovered meta- surable before symptoms are present. This opens the way to- bolic patterns that are predictive of heart attacks and breast ward true preventive actions against this dangerous disease. cancer by means of analysis of a tiny drop of urine – before symptoms arise and before medical diagnosis takes place. More remarkably, OISM scientists have now found meta- bolic patterns in human urine that are predictive of heart As we live, our bodies produce thousands of different attacks – measurable before symptoms are present, even in chemicals required for life and many that are discarded as well people with no history of heart disease. -

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463 Daniel W

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463 Daniel W. Meek, Esq. FEB \ 0 IW Portland, OR 97219 RE; MUR 6846 DeFazio for Congress and Jef A Green in his official capacity as treasurer I Dear Mr. Meek; On July 1, 2014, the Federal Election Commission (the "Commission") notified DeFazio ? for Congress and its treasurer, your clients, of a complaint alleging violations of certain sections ? of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended (the "Act") and Commission regulations. A copy of the complaint was forwarded to your clients at that time. On February 7, 2017, the Commission found, on the basis of the information in the complaint, and information provided by DeFazio for Congress and Jef A Green in his official capacity as treasurer ("Committee"), that there is no reason to believe that the Committee violated 52 U.S.C. § 30120 with respect to allegations that its website lacked an adequate disclaimer. In addition, the Commission found no reason to believe that the Committee violated 52 U.S.C. § 30124(a)(1) with respect to allegations that it fi-audulently misrepresented its billboards and a website as belonging to the Art Robinson campaign. Finally, the Commission dismissed the allegations that the Committee violated 52 U.S.C. § 30120 by failing to include adequate disclaimers on its billboards. Accordingly, the Commission closed the file in this matter. Political committees must include a disclaimer on all public communications, which includes outdoor advertising facilities, such as billboards. See 52 U.S.C. § .30120; 11 C.F.R. §§ 100.26, 110.11(a)(1). -

Bulletin Table of Contents

Bulletin 2016-2017 Table of Contents The Seal ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 Mission ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 History. .7 Campus . .9 Trustees, Administration, Staff. .12 Faculty. .15 Academic Policies and Procedures ����������������������������������������������������������������������24 Constantin College of Liberal Arts . .37 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business (Undergraduate) . .42 Campus Life. .43 Undergraduate Enrollment . .52 Undergraduate, Braniff Graduate School, and Neuhoff School of Ministry Fees and Expenses . .60 Undergraduate Scholarships and Financial Aid ����������������������������������������������������69 Requirements for the Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science Degrees ��������������74 Course Descriptions by Department. .78 Rome and Summer Programs . .264 Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts . .279 The Institute of Philosophic Studies Doctoral Program ������������������������������������287 Braniff Graduate Master's Programs . .303 Ann & Joe O. Neuhoff School of Ministry ����������������������������������������������������������341 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business (Graduate) ��������������������������������������359 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business (Graduate) Calendar . .402 Undergraduate, Braniff Graduate School, and Neuhoff School of Ministry Calendar ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������405 -

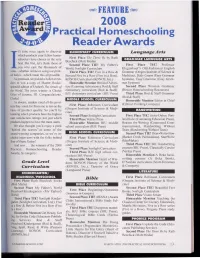

Practical Homeschooling Magazine Annual Reader Awards

FEATURE 2008 Practical Homeschooling Reader Awards ts time once again to discover ELEMENTARY CURRICULUM Language Arts which products your fellow home- First Place The Three Rs by Ruth schoolers have chosen as the very GRAMMAR LANGUAGE ARTS Beechick (Mott Media) best. But first, lets thank those of Second Place TIE! My Fathers First Place TIE! Professor you who cast the thousands of World, Sonlight Curriculum Klugimkopfs Old-Fashioned English votes—whether1 online or using our print- Third Place TIE! Five in a Row Grammar (Oregon Institute of Science ed ballot—which made this all possible. Beyond Five in a Row (Five in a Row), Medicine), Daily Grams (Easy Grammar As promised, we picked a ballot at ran- KONOS Curriculum (KONOS, Inc.) Systems), Easy Grammar (Easy Gram- dom to win a copy of Master Books Honorable Mention World of Adven- mar Systems) splendid edition of Usshers The Annals of ture (Learning Adventures), Rod Staff Second Place Winston Grammar the World. The prize winner is Chalee elementary curriculum (Rod Staff), (Hewitt Homeschooling Resources) Giles of Jerome, ID. Congratulations, BJU elementary curriculum (BJU Press) Third Place Rod Staff Grammar Chalee! (Rod Staff) MIDDLE SCHOOL CURRICULUM Honorable Mention Editor in Chief As always, readers rated all the prod- (Critical Thinking Company) ucts they voted for from one to ten on the First Place Robinson Curriculum (Oregon Institute of Science Medi- basis of product quality. So youll be HANDWRITING cine) learning which products have the highest Second Place Sonlight Curriculum First Place TIE! Getty-Dubay Port- user satisfaction ratings, not just which Third Place Veritas Press land Italic (Continuing Education Press), products happen to have the most users. -

201026 Obiter Dicta: Autumn Mid-Term 2010

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Helms School of Government 10-2010 201026 OBITER DICTA: AUTUMN MID-TERM 2010 Steven Alan Samson Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Samson, Steven Alan, "201026 OBITER DICTA: AUTUMN MID-TERM 2010" (2010). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 348. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Helms School of Government at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 201026 OBITER DICTA: AUTUMN MID-TERM 2010 Steven Alan Samson Thursday, October 21, 2010 http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703794104575546611651621270.html The decimation of Eastern Europe under Stalin, Hitler, et al. http://www.mediaite.com/online/rachel-maddow-gets-in-epic-battle-with-gop- congressional-candidate-art-robinson/ Here is Rachel Maddow versus my future Oregon congressman, Art Robinson, who has astronauts endorsing him. Art founded a research institute in Cave Junction and had been a research associate of Linus Pauling a long time ago. He developed a home school curriculum (available for $10 on DVD) for his large family after his wife, who was also a research scientist, suddenly died in the late 1980s. Art coauthored a book with Gary North a few years earlier and, in the 1990s, took over editing Petr Beckmann's Access to Energy. -

OREGON STATE SENATORS and REPRESENTATIVES 2021 Legislative Session * Denotes That Only a Few City Precincts Are Located in That District

OREGON STATE SENATORS AND REPRESENTATIVES 2021 Legislative Session * Denotes that only a few city precincts are located in that district SENATE HOUSE D: 18 R: 12 D: 37 R: 23 City Senator(s) District Representative(s) District Adair Village Brian Boquist (R) 12 Mike Nearman (R) 23 Adams Bill Hansell (R) 29 Bobby Levy (R) 58 Adrian Lynn Findley (R ) 30 Mark Owens (R) 60 Albany Sara Gelser (D) 8 Shelly Boshart Davis (R) 15 Amity Brian Boquist (R) 12 Mike Nearman (R) 23 Antelope Bill Hansell (R) 29 Greg Smith (R) 57 Arlington Bill Hansell (R) 29 Greg Smith (R) 57 Ashland Jeff Golden (D) 3 Pam Marsh (D) 5 Astoria Betsy Johnson (D) 16 Suzanne Weber (R) 32 Athena Bill Hansell (R) 29 Bobby Levy (R) 58 Aumsville Deb Patterson (D) 10 Raquel Moore-Green (R) 19 Aurora Fred Girod (R) 9 Rick Lewis (R) 18 Baker City Lynn Findley (R ) 30 Mark Owens (R) 60 Bandon Dallas Heard (R) 1 David Brock Smith (R) 1 Banks Betsy Johnson (D) 16 Suzanne Weber (R) 32 Barlow Open Seat (R) 20 Christine Drazan (R) 39 Bay City Betsy Johnson (D) 16 Suzanne Weber (R) 32 Beaverton Kate Lieber (D) 14 Sheri Schouten (D) 27 Elizabeth Steiner Wlnsvey Campos (D) 28 17 Hayward (D) Maxine Dexter (D) 33 Ginny Burdick (D) 18 Ken Helm (D) 34 Dacia Grayber (D) 35 Bend Tim Knopp (R) 27 Jason Kropf (D) 54 Boardman Bill Hansell (R) 29 Greg Smith (R) 57 City Senator(s) District Representative(s) District Bonanza Dennis Linthicum (R) 28 Werner Reschke (R) 56 Brookings Dallas Heard (R) 1 David Brock Smith (R) 1 Brownsville Lee Beyer (D) 6 Marty Wilde (D) 11 Burns Lynn Findley (R ) 30 Mark -

Northumbria Research Link

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Ruiu, Maria Laura (2019) Moral panics and newspaper reporting in Britain: between sceptical and realistic discourses of climate change. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/42051/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/pol i cies.html MORAL PANICS AND NEWSPAPER REPORTING IN BRITAIN: BETWEEN SCEPTICAL AND REALISTIC DISCOURSES OF CLIMATE CHANGE Volume 1 of 2 M L Ruiu PhD 2019 MORAL PANICS AND NEWSPAPER REPORTING IN BRITAIN: BETWEEN SCEPTICAL AND REALISTIC DISCOURSES OF CLIMATE CHANGE Volume 1 of 2 Maria Laura Ruiu A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences July 2019 Abstract This thesis provides the first attempt to empirically apply the moral panic framework to study British newspaper reporting on climate change by drawing upon a unique dataset of 958 news articles over three decades (1988-2016). -

Independent Expenditures and Electioneering Communication Expenditures Reported to the Federal Election Commission

March 2013 www.citizen.org October 24, 2012 Super Connected Outside Groups’ Devotion to Individual Candidates and Political Parties Disproves the Supreme Court’s Key Assumption in Citizens United That Unregulated Outside Spenders Would Be ‘Independent’ (UPDATED VERSION OF OCTOBER 2012 REPORT, WITH REVISED DATA AND DISCUSSION OF THE ‘SOFT MONEY’ IMPLICATIONS OF CITIZENS UNITED) Acknowledgments This report was written by Taylor Lincoln, research director of Public Citizen’s Congress Watch division. Congress Watch Legislative Assistant Kelly Ngo assisted with research. Congress Watch Director Lisa Gilbert edited the report. Public Citizen Litigation Group Senior Attorney Scott Nelson provided expert advice. This report draws in part on a May 2012 amicus brief to the Supreme Court that was coauthored by Nelson. About Public Citizen Public Citizen is a national non-profit organization with more than 300,000 members and supporters. We represent consumer interests through lobbying, litigation, administrative advocacy, research, and public education on a broad range of issues including consumer rights in the marketplace, product safety, financial regulation, worker safety, safe and affordable health care, campaign finance reform and government ethics, fair trade, climate change, and corporate and government accountability. Public Citizen’s Congress Watch 215 Pennsylvania Ave. S.E Washington, D.C. 20003 P: 202-546-4996 F: 202-547-7392 http://www.citizen.org © 2013 Public Citizen. Public Citizen Super Connected Methodology and Definitions . This report represents a substantial update of a report published in October 2012, available at http://www.citizen.org/documents/super-connected-candidate-super-pacs-not- independent-report.pdf. Most of the data used in this report was drawn from the Center for Responsive Politics (www.opensecrets.org) or the Sunlight Foundation (http://sunlightfoundation.com). -

SENATE COMMITTEE on EDUCATION AGENDA Revision 1

Staff: Members: Matt Perreault, LPRO Analyst Sen. Michael Dembrow, Chair Lisa Gezelter, LPRO Analyst Sen. Chuck Thomsen, Vice-Chair Maia Daniel, Committee Assistant Sen. Sara Gelser Sen. Chris Gorsek Sen. Art Robinson SENATE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION Oregon State Capitol 900 Court Street NE, Room 453, Salem, Oregon 97301 Phone: 503-986-1665 Email: https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2021R1/Testimony/SED AGENDA Revision 1 Posted: MAR 19 01:26 PM MONDAY Date: March 22, 2021 Time: 3:15 P.M. Room: Remote B Entry to the Capitol Building is currently limited to authorized personnel only. All committee meetings are taking place remotely. To view a live stream of the meeting: https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2021R1/Committees/SED/Overview A viewing station is also available outside of the Capitol Building. Instructions on how to submit written testimony and how to register to testify appear at the bottom of the agenda. Please note: SB 478, SB 486, and SB 487 are scheduled solely for the purpose of holding the record open. No testimony will be taken. Public Hearing SB 478 Directs Department of Education to conduct study related to identification of talented and gifted children and to report results of study to interim committee of Legislative Assembly related to education. SB 486 Modifies requirements of plans of instruction for talented and gifted children. SB 487 Directs Department of Education to conduct study on instruction provided to talented and gifted children and to report results of study to interim committee of Legislative Assembly related to education. SB 416 Requires community colleges to allow each criminal justice course offered by college to be eligible course for social science cluster portion of associate degree. -

2020 Oregon Primary Election Results Unofficial Results As of 5/20/2020

2020 Oregon Primary Election Results Unofficial results as of 5/20/2020 https://results.oregonvotes.gov/Default.aspx Congressional District Incumbent Democrat Republican U.S. Senator Jeff Merkley Jeff Merkley Jo Rae Perkins U.S. Rep - 1 Suzanne Bonamici - D Suzanne Bonamici Christopher Christensen U.S. Rep - 2 Greg Walden - R Alex Spenser Cliff Bentz Nick Heuertz Knute Buehler U.S. Rep - 3 Earl Blumenauer - D Earl Blumenauer Joanna Harbour U.S. Rep - 4 Peter DeFazio Peter DeFazio Alek Skarlatos U.S. Rep - 5 Kurt Schrader - D Kurt Schrader Amy Ryan Courser Secretary of State Incumbent Democrat Republican Bev Clarno Mark D Hass - 35.96% Kim Thatcher Shemia Fagan - 35.32% Jamie McLeod-Skinner - 27.95% State Senate District Incumbent Democrat Republican 1 Dallas Heard - R Kat Stone Dallas Heard 2 Herman Baertschiger - R Jerry Allen Art Robinson 3 Jeff Golden - D 4 Floyd Prozanski - D 5 Arnie Roblan - D Melissa T Cribbins Dick Anderson 6 Lee Beyer - D 7 James Manning - D 8 Sara Gelser - D 9 Fred Girod - R Jim Hinsvark Fred Girod 10 Denyc Boles - R Deb Patterson Denyc Boles 11 Peter Courtney - D 12 Brian Boquist - R Bernadette Hansen Brian Boquist Ross Swartzendruber 13 Kim Thatcher - R 14 Mark Hass - D Kate Lieber Harmony K Mulkey 15 Chuck Riley - D 16 Betsy Johnson - D 17 E. Steiner Hayward - D 18 Ginny Burdick - D Ginny Burdick 19 Robert Wagner - D 20 Alan Olsen - R 21 Kathleen Taylor - D Kathleen Taylor 22 Lew Frederick - D Lew Frederick 23 Michael Dembrow - D Michael Dembrow 24 Shemia Fagan - D 25 L. -

Don't Tread on Me: Analyzing the Effects of the Tea Party on Voting

Don’t Tread on Me: Analyzing the Effects of the Tea Party on Voting Patterns of House Democrats Nicole DeMont Department of Communication Stanford University Advisor: Shanto Iyengar June 4, 2014 Abstract: The Tea Party reached its peak during the 2010 midterm elections and helped propel Republicans into the House of Representatives. While commentary has focused on the Republican Party’s shift to the right in response to the Tea Party movement, this paper examines the Tea Party’s influence on the Democratic Party. Using Washington Post data on party voting, I find that Democrats who beat Tea Party candidates in competitive races are 6.5 percent more likely to vote with the Democratic Party in the congressional session following the 2010 midterm election. This brings the likelihood of voting with the Party up to 89.4 percent on any given vote, compared to the baseline of 82.9 percent. Possible explanations for this Tea Party effect are presented. Amid the mounting concern over the national debt and the size of the federal government, the Tea Party movement emerged in early 2009. On Tax Day, April 15, 2009, in what would be one of the largest rallies the movement would see, Tea Party protests took place in over 750 cities across the country. President Obama’s proposed healthcare bill only fueled the growth and frustrations of the Tea Party movement. Although the Democratic leadership, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, had originally dismissed the movement, by August 2009 the Democrats were forced to pay attention.