Download Transcript (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epigenetic Regulation of the Human Genome by Transposable Elements

EPIGENETIC REGULATION OF THE HUMAN GENOME BY TRANSPOSABLE ELEMENTS A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty By Ahsan Huda In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Bioinformatics in the School of Biology Georgia Institute of Technology August 2010 EPIGENETIC REGULATION OF THE HUMAN GENOME BY TRANSPOSABLE ELEMENTS Approved by: Dr. I. King Jordan, Advisor Dr. John F. McDonald School of Biology School of Biology Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Leonardo Mariño-Ramírez Dr. Jung Choi NCBI/NLM/NIH School of Biology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Soojin Yi, School of Biology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: June 25, 2010 To my mother, your life is my inspiration... ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am evermore thankful to my advisor Dr. I. King Jordan for his guidance, support and encouragement throughout my years as a PhD student. I am very fortunate to have him as my mentor as he is instrumental in shaping my personal and professional development. His contributions will continue to impact my life and career and for that I am forever grateful. I am also thankful to my committee members, John McDonald, Leonardo Mariño- Ramírez, Soojin Yi and Jung Choi for their continued support during my PhD career. Through my meetings and discussions with them, I have developed an appreciation for the scientific method and a thorough understanding of my field of study. I am especially grateful to my friends and colleagues, Lee Katz and Jittima Piriyapongsa for their support and presence, which brightened the atmosphere in the lab in the months and years past. -

2017 Bring Your Kids to Campus Day Schedule of Events

2017 Bring Your Kids to Campus Day Schedule of Events Puppets & Stories: Drop in 9-11am Milam 215 Recommended Ages: 3-12 years old Watch puppets tell stories, or write a play, create puppets and perform your own story. What fun! Be a #BrainBuilder! Hosted by the Oregon Parenting Education Collaborative: Drop in 9-11am Hallie E Ford 1st Floor Lobby Recommended Ages: 0-8 years Stop by for temporary tattoos, stickers, and more! Come participate in fun brain building activities that promote healthy relationships between parents and children! Learn about Vroom and other family activities and resources in the community. “Oh the Places You’ll Go” with ASOSU: Drop in 9am-12pm SEC 250 Recommended Ages: All We will have a Photo Booth set up for kids to take photos to remember their special day on campus. Additionally, we will have a space for the children to create a drawing and then create a button using their personal design and a button maker. (This activity will be appropriate for all ages and younger children can be assisted by ASOSU staff) We will also have a coloring station for kids to color different pre-printed sheets (or design their own) while they wait their turn to make a button. Wood Magic- Bubbling Bazookas: Drop in 9am-12pm Richardson Hall 107 Recommended Ages: 2 years and above Come explore an interactive experience designed to educate children about the wonders of wood as a material. Test Your Sense of Taste!: Drop in 9am-2pm Wiegand Hall 204 Recommended Ages: 5-14 years Experience first-hand the science of the senses! Come be a “taste tester” and take our fun test in one of the official booths to see how well you can identify flavors when some of the usual clues are missing. -

OSU Libraries and Press Annual Report, 2012-2013

OSU Libraries and Press Annual Report, 2012-2013 PROGRAMMATIC ACHIEVEMENTS 1A. Student engagement and success Instruction: Center for Digital Scholarship Services (CDSS) faculty taught several workshops and conducted numerous consultations for graduate students on copyright permissions and fair use. These activities led to a number of graduate students strengthening their research through the use of copyrighted images, which they'd either been advised to remove or had decided to remove themselves because of copyright concerns. Special Collections and Archive Research Center (SCARC) faculty: engaged with more than 2,000 people, an increase of 64 percent over 2011-2012. This includes 1,226 students in course-related instruction and 755 people (including students) in tours or orientations of SCARC. co-taught the Honors College course TCE 408H “Sundown Towns in Oregon” with Professor Jean Moule, fall 2012. The class's four students co-curated a display featured in The Valley Library’s 5th floor exhibit area. worked with SOC 518 “Qualitative Research Methods” students to develop six oral histories of individuals important to OSU history. These student-conducted interviews have since been deposited in a dedicated SCARC oral history collection and were featured in a Valley Library exhibit case. collaborated with students in the History course HST 415/515 “Digital History” to develop a web site on the history of Waldo Hall – based on research in SCARC collection by undergraduates who selected content and wrote text for the Waldo Hall online exhibit. OSU Press staff met with the following classes at OSU and other universities and schools: WR 362 Science Writing, in the OSU School of Writing, Literature, and Film; John Witte’s editing class at the University of Oregon; Scott Slovic’s editing/publishing class at the University of Idaho; Roosevelt High School Publishing and Writing Center in Portland. -

California Tech That, for the First Time Since the Will Report on His Recent Trav Affairs Officer

CaliforniaTech Associated Students of the California Institute of Technology Volume LXII. Pasadena, California, Thurs'day, February 16, 1961 Number 18 ASCIT Elections Next Tuesday Russ, Sallee Annual Rally Hughes Win Set Monday Travel Prizes Tuesday's elections, preceded by the election rally on Monday Junior Travel Prizes for this night, features Bob Koh and year were announced by Dr. Dave Pritchard battling for the Horace Gilbert, Professor of Eco- office of ASCIT President, as nomics. The winners are Evan well as 18 others running for Hughes, Jr., John Russ, and the remaining offices. George Sallee. The winners, were Candidates' statements appear chosen from among 11 complet on pages 4 and 5 of tliis issue. ed applications. The candidates have also been campaigning in the Student Each of the recipients of a Houses and have posters on dis travel prize must select a proj play. ect which they wish to study on their trip. This project, how The nominees are: ever, is not meant to be an all ASCIT President-Bob Koh, encompassing work of art. The Candidates (front row): Bruce, Abell, Dave Benson, Jon Kelly; (second row): Lance Taylor, Jim Dave Pritchard principal purpose of the project Sagawa, Lee Molho, Howard Monell, Pete Metcalf, Jim Geddis; (back row): Art Robinson, Don O'Hara, Vice-President-Dean Gerber is that it serves as an excuse George McBean, John Golden, John Arndt. Secretary-Art Robinson to make contact with other peo Treasurer-Jim Geddis, John ple, making the trip more than Trustees Pick Golden just an average tour. Sallee's Hanna Concludes AUFS Series; Athletic Manager-John Arndt project is a study of the Euro Business Manager-Jim Sagawa pean beet sugar industry, while New Members Activities Chairman-Jon Kelly Russ will study German and To Dicuss Sf Asia Problems Three eastern business execu Social Chairman-Pete Metcalf, British church music and tives have been elected to the Howard Monell BY MATT COUCH senior posts in the U.S. -

Downloaded on January 1, 1998

OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY LFACT BOOK i.990 ',- - A- - 1 I I r. nrn j nD I ipiJgI_______dIl I I OSU's Library: A Key Component of the University's Mission for 130 Years Since its designation as Oregon's land grant institution in 1868, Oregon State University's library has played a significant role in fulfilling the University's mission. During the past 130 years, that role has necessitated constant upgrading and expansion of the library's physical infrastructure. The first college library was housed in a modest 5-foot-square room in the same building in downtown Corvallis that served all of Corvallis College's academic and administrative needs. The library received its first major gift in 1880 when the defunct Corvallis Library Association turned over its collection of 605 volumes to the college's Adeiphian Literary Society. With the completion in 1889 of the new College Building (now Benton Hall), west of downtown, the library was moved to new quarters on the building's third floor. By 1899, when the first nonstudent college librarian was appointed, the college catalog listed the library's holdings at 3,000 volumes and 5,000 pamphlets and bulletins. In 1908, Ida A. Kidder was appointed as Oregon Agricultural College's first professional librarian. She began a 12-year period of growth unparalleled in the library's history the library's holdings increased by 800 percent, its staff increased from one position to nine, and to accommodate these increases in books and staff, Kidder planned and oversaw the construction of a new 57,000-square-foot library building. -

Maret Traber. Ph.D

Maret G. Traber, Ph.D. Linus Pauling Institute, 451 Linus Pauling Science Center Oregon State University Corvallis, OR 97331-6512 Phone: 541-737-7977; Fax: 541-737-5077; email: [email protected] EDUCATION Location Degree Year Major University of California, Berkeley, CA B.S. 1972 Nutrition and Food Science University of California, Berkeley, CA Ph.D. 1976 Nutrition RESEARCH AND PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Year Position Institution 1972-76 Research Assistant University of California, Berkeley, CA 1976-77 Instructor of Nutrition Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 1977-80 Assistant Research Scientist Department of Medicine, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY 1980-83 Associate Research Scientist 1983-86 Research Scientist 1986-89 Research Assistant Professor 1989-93 Research Associate Professor 1994-98 Associate Research Department of Molecular & Cell Biology, Biochemist University of California, Berkeley, CA 1997-2002 Associate Research Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Critical Biochemist Care Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA 1998-present Principal Investigator Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 1998-2002 Associate Professor Department of Nutrition and Food Management Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 1999-present Member Molecular and Cell Biology Graduate Group, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 2002-present Professor Nutrition Program, School of Biological & Population Health Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 2011-present Helen P. -

The Struggle for Life of the Genomels Selfish Architects

Hua-Van et al. Biology Direct 2011, 6:19 http://www.biology-direct.com/content/6/1/19 REVIEW Open Access The struggle for life of the genome’s selfish architects Aurélie Hua-Van*, Arnaud Le Rouzic, Thibaud S Boutin, Jonathan Filée and Pierre Capy Abstract Transposable elements (TEs) were first discovered more than 50 years ago, but were totally ignored for a long time. Over the last few decades they have gradually attracted increasing interest from research scientists. Initially they were viewed as totally marginal and anecdotic, but TEs have been revealed as potentially harmful parasitic entities, ubiquitous in genomes, and finally as unavoidable actors in the diversity, structure, and evolution of the genome. Since Darwin’s theory of evolution, and the progress of molecular biology, transposable elements may be the discovery that has most influenced our vision of (genome) evolution. In this review, we provide a synopsis of what is known about the complex interactions that exist between transposable elements and the host genome. Numerous examples of these interactions are provided, first from the standpoint of the genome, and then from that of the transposable elements. We also explore the evolutionary aspects of TEs in the light of post-Darwinian theories of evolution. Reviewers: This article was reviewed by Jerzy Jurka, Jürgen Brosius and I. King Jordan. For complete reports, see the Reviewers’ reports section. Background 1930s and 1940s by Fisher, Wright, Haldane, Dobz- For a century and half, from the publication of “On the hansky, Mayr, and Simpson among others), and finally Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the molecular dimension (Kimura’s neutral evolution the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for theory, Pauling and Zuckerkandl’s molecular clock con- Life“ by Darwin [1] to the present day, thinking about cept). -

Urine Sample Bank

Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine 2251 Dick George Rd., Cave Junction, OR 97523 We are working to bring advanced technology for diagnostic and preventive medicine to the American people. symptoms. It is of great importance to detect breast cancer Medical Break-through at the early in this process, take steps to prevent it, and – if it oc- Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine curs – to monitor it very carefully during medical therapy. It is best to detect breast cancer so early that the increased Scientists at the Oregon Institute of Science and Medi- probability of the disease can be fought therapeutically by cine, a nonprofit research institute, have been working to less invasive means, rather than waiting until disease symp- improve diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive medicine. toms arrive and require severe, less effective treatment. Now, they have made a remarkable break-through. OISM scientists have found metabolic patterns in human As reported in the Fall 2017 issue of the Journal of Ameri- urine that are predictive of developing breast cancer – mea- can Physicians and Surgeons, they have discovered meta- surable before symptoms are present. This opens the way to- bolic patterns that are predictive of heart attacks and breast ward true preventive actions against this dangerous disease. cancer by means of analysis of a tiny drop of urine – before symptoms arise and before medical diagnosis takes place. More remarkably, OISM scientists have now found meta- bolic patterns in human urine that are predictive of heart As we live, our bodies produce thousands of different attacks – measurable before symptoms are present, even in chemicals required for life and many that are discarded as well people with no history of heart disease. -

Dr Hugh Riordan Vitamin C Maverick Slides 1 - 45 O

Riordan Clinic IVC Academy Dr Hugh Riordan Vitamin C Maverick Slides 1 - 45 O © Riordan Clinic 2018 Dr. Hugh Riordan Vitamin C Maverick Ron Hunninghake M.D. Chief Medical Officer Riordan Clinic “One man with courage makes a majority.” Andrew Jackson Riordan Clinic www.riordanclinic.org Dedication • Dr. Hugh D. Riordan • Founder of Riordan Clinic • The Hugh D. Riordan Professorship in Orthomolecular Medicine • The 45th endowed professorship at Kansas Univ. School of Medicine 1932 - 2005 “The Hugh D. Riordan, MD, Professorship in Orthomolecular Medicine at KU Endowment honors the memory of Riordan, a pioneer in the field of complementary and alternative medicine, who died in January of 2005. He was a strong supporter of orthomolecular medicine, the practice of preventing and treating disease by providing the body with optimal amounts of natural substances.” KUMC News Bulletin Continuing Pauling’s Legacy Orthomolecular is the “right molecule” - Linus Pauling, PhD • Two-time Nobel Prize winner • Molecular Biologist • Coined the term “Orthomolecular” 1968 Science* article “Orthomolecular Psychiatry” *www.orthomolecular.org Hall of Fame 2004 1901 - 1994 “In the fields of observation… chance favors the prepared mind.” Dans les champs de l'observation le hasard ne favorise que les esprits préparés. Louis Pasteur 1822 - 1895 The Island of Curacao 1492 • Legend has it that several sailors from Christopher Columbus’ voyage to the new world developed scurvy • Feeling very sick and referring not to die at sea, they were dropped off on an uncharted Caribbean Island • Months later, the returning crew were all shocked and surprised to see these men, who were thought to be surely dead, waving to them from the shores, alive and healthy! • The island was named Curacao, meaning Cure. -

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463 Daniel W

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463 Daniel W. Meek, Esq. FEB \ 0 IW Portland, OR 97219 RE; MUR 6846 DeFazio for Congress and Jef A Green in his official capacity as treasurer I Dear Mr. Meek; On July 1, 2014, the Federal Election Commission (the "Commission") notified DeFazio ? for Congress and its treasurer, your clients, of a complaint alleging violations of certain sections ? of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended (the "Act") and Commission regulations. A copy of the complaint was forwarded to your clients at that time. On February 7, 2017, the Commission found, on the basis of the information in the complaint, and information provided by DeFazio for Congress and Jef A Green in his official capacity as treasurer ("Committee"), that there is no reason to believe that the Committee violated 52 U.S.C. § 30120 with respect to allegations that its website lacked an adequate disclaimer. In addition, the Commission found no reason to believe that the Committee violated 52 U.S.C. § 30124(a)(1) with respect to allegations that it fi-audulently misrepresented its billboards and a website as belonging to the Art Robinson campaign. Finally, the Commission dismissed the allegations that the Committee violated 52 U.S.C. § 30120 by failing to include adequate disclaimers on its billboards. Accordingly, the Commission closed the file in this matter. Political committees must include a disclaimer on all public communications, which includes outdoor advertising facilities, such as billboards. See 52 U.S.C. § .30120; 11 C.F.R. §§ 100.26, 110.11(a)(1). -

Bulletin Table of Contents

Bulletin 2016-2017 Table of Contents The Seal ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 Mission ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 History. .7 Campus . .9 Trustees, Administration, Staff. .12 Faculty. .15 Academic Policies and Procedures ����������������������������������������������������������������������24 Constantin College of Liberal Arts . .37 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business (Undergraduate) . .42 Campus Life. .43 Undergraduate Enrollment . .52 Undergraduate, Braniff Graduate School, and Neuhoff School of Ministry Fees and Expenses . .60 Undergraduate Scholarships and Financial Aid ����������������������������������������������������69 Requirements for the Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science Degrees ��������������74 Course Descriptions by Department. .78 Rome and Summer Programs . .264 Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts . .279 The Institute of Philosophic Studies Doctoral Program ������������������������������������287 Braniff Graduate Master's Programs . .303 Ann & Joe O. Neuhoff School of Ministry ����������������������������������������������������������341 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business (Graduate) ��������������������������������������359 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business (Graduate) Calendar . .402 Undergraduate, Braniff Graduate School, and Neuhoff School of Ministry Calendar ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������405 -

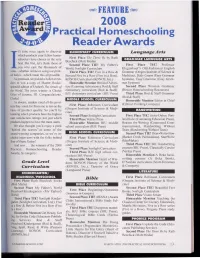

Practical Homeschooling Magazine Annual Reader Awards

FEATURE 2008 Practical Homeschooling Reader Awards ts time once again to discover ELEMENTARY CURRICULUM Language Arts which products your fellow home- First Place The Three Rs by Ruth schoolers have chosen as the very GRAMMAR LANGUAGE ARTS Beechick (Mott Media) best. But first, lets thank those of Second Place TIE! My Fathers First Place TIE! Professor you who cast the thousands of World, Sonlight Curriculum Klugimkopfs Old-Fashioned English votes—whether1 online or using our print- Third Place TIE! Five in a Row Grammar (Oregon Institute of Science ed ballot—which made this all possible. Beyond Five in a Row (Five in a Row), Medicine), Daily Grams (Easy Grammar As promised, we picked a ballot at ran- KONOS Curriculum (KONOS, Inc.) Systems), Easy Grammar (Easy Gram- dom to win a copy of Master Books Honorable Mention World of Adven- mar Systems) splendid edition of Usshers The Annals of ture (Learning Adventures), Rod Staff Second Place Winston Grammar the World. The prize winner is Chalee elementary curriculum (Rod Staff), (Hewitt Homeschooling Resources) Giles of Jerome, ID. Congratulations, BJU elementary curriculum (BJU Press) Third Place Rod Staff Grammar Chalee! (Rod Staff) MIDDLE SCHOOL CURRICULUM Honorable Mention Editor in Chief As always, readers rated all the prod- (Critical Thinking Company) ucts they voted for from one to ten on the First Place Robinson Curriculum (Oregon Institute of Science Medi- basis of product quality. So youll be HANDWRITING cine) learning which products have the highest Second Place Sonlight Curriculum First Place TIE! Getty-Dubay Port- user satisfaction ratings, not just which Third Place Veritas Press land Italic (Continuing Education Press), products happen to have the most users.