Electromagnetic Fields and Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Introduction to Electrostatics

Chapter 2 Introduction to electrostatics 2.1 Coulomb and Gauss’ Laws We will restrict our discussion to the case of static electric and magnetic fields in a homogeneous, isotropic medium. In this case the electric field satisfies the two equations, Eq. 1.59a with a time independent charge density and Eq. 1.77 with a time independent magnetic flux density, D (r)= ρ (r) , (1.59a) ∇ · 0 E (r)=0. (1.77) ∇ × Because we are working with static fields in a homogeneous, isotropic medium the constituent equation is D (r)=εE (r) . (1.78) Note : D is sometimes written : (1.78b) D = ²oE + P .... SI units D = E +4πP in Gaussian units in these cases ε = [1+4πP/E] Gaussian The solution of Eq. 1.59 is 1 ρ0 (r0)(r r0) 3 D (r)= − d r0 + D0 (r) , SI units (1.79) 4π r r 3 ZZZ | − 0| with D0 (r)=0 ∇ · If we are seeking the contribution of the charge density, ρ0 (r) , to the electric displacement vector then D0 (r)=0. The given charge density generates the electric field 1 ρ0 (r0)(r r0) 3 E (r)= − d r0 SI units (1.80) 4πε r r 3 ZZZ | − 0| 18 Section 2.2 The electric or scalar potential 2.2 TheelectricorscalarpotentialFaraday’s law with static fields, Eq. 1.77, is automatically satisfied by any electric field E(r) which is given by E (r)= φ (r) (1.81) −∇ The function φ (r) is the scalar potential for the electric field. It is also possible to obtain the difference in the values of the scalar potential at two points by integrating the tangent component of the electric field along any path connecting the two points E (r) d` = φ (r) d` (1.82) − path · path ∇ · ra rb ra rb Z → Z → ∂φ(r) ∂φ(r) ∂φ(r) = dx + dy + dz path ∂x ∂y ∂z ra rb Z → · ¸ = dφ (r)=φ (rb) φ (ra) path − ra rb Z → The result obtained in Eq. -

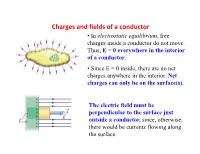

Charges and Fields of a Conductor • in Electrostatic Equilibrium, Free Charges Inside a Conductor Do Not Move

Charges and fields of a conductor • In electrostatic equilibrium, free charges inside a conductor do not move. Thus, E = 0 everywhere in the interior of a conductor. • Since E = 0 inside, there are no net charges anywhere in the interior. Net charges can only be on the surface(s). The electric field must be perpendicular to the surface just outside a conductor, since, otherwise, there would be currents flowing along the surface. Gauss’s Law: Qualitative Statement . Form any closed surface around charges . Count the number of electric field lines coming through the surface, those outward as positive and inward as negative. Then the net number of lines is proportional to the net charges enclosed in the surface. Uniformly charged conductor shell: Inside E = 0 inside • By symmetry, the electric field must only depend on r and is along a radial line everywhere. • Apply Gauss’s law to the blue surface , we get E = 0. •The charge on the inner surface of the conductor must also be zero since E = 0 inside a conductor. Discontinuity in E 5A-12 Gauss' Law: Charge Within a Conductor 5A-12 Gauss' Law: Charge Within a Conductor Electric Potential Energy and Electric Potential • The electrostatic force is a conservative force, which means we can define an electrostatic potential energy. – We can therefore define electric potential or voltage. .Two parallel metal plates containing equal but opposite charges produce a uniform electric field between the plates. .This arrangement is an example of a capacitor, a device to store charge. • A positive test charge placed in the uniform electric field will experience an electrostatic force in the direction of the electric field. -

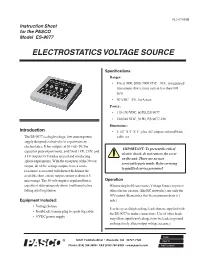

Electrostatics Voltage Source

012-07038B Instruction Sheet for the PASCO Model ES-9077 ELECTROSTATICS VOLTAGE SOURCE Specifications Ranges: • Fixed 1000, 2000, 3000 VDC ±10%, unregulated (maximum short circuit current less than 0.01 mA). • 30 VDC ±5%, 1mA max. Power: • 110-130 VDC, 60 Hz, ES-9077 • 220/240 VDC, 50 Hz, ES-9077-220 Dimensions: Introduction • 5 1/2” X 5” X 1”, plus AC adapter and red/black The ES-9077 is a high voltage, low current power cable set supply designed exclusively for experiments in electrostatics. It has outputs at 30 volts DC for IMPORTANT: To prevent the risk of capacitor plate experiments, and fixed 1 kV, 2 kV, and electric shock, do not remove the cover 3 kV outputs for Faraday ice pail and conducting on the unit. There are no user sphere experiments. With the exception of the 30 volt serviceable parts inside. Refer servicing output, all of the voltage outputs have a series to qualified service personnel. resistance associated with them which limit the available short-circuit output current to about 8.3 microamps. The 30 volt output is regulated but is Operation capable of delivering only about 1 milliamp before When using the Electrostatics Voltage Source to power falling out of regulation. other electric circuits, (like RC networks), use only the 30V output (Remember that the maximum drain is 1 Equipment Included: mA.). • Voltage Source Use the special high-voltage leads that are supplied with • Red/black, banana plug to spade lug cable the ES-9077 to make connections. Use of other leads • 9 VDC power supply may allow significant leakage from the leads to ground and negatively affect output voltage accuracy. -

Quantum Mechanics Electromotive Force

Quantum Mechanics_Electromotive force . Electromotive force, also called emf[1] (denoted and measured in volts), is the voltage developed by any source of electrical energy such as a batteryor dynamo.[2] The word "force" in this case is not used to mean mechanical force, measured in newtons, but a potential, or energy per unit of charge, measured involts. In electromagnetic induction, emf can be defined around a closed loop as the electromagnetic workthat would be transferred to a unit of charge if it travels once around that loop.[3] (While the charge travels around the loop, it can simultaneously lose the energy via resistance into thermal energy.) For a time-varying magnetic flux impinging a loop, theElectric potential scalar field is not defined due to circulating electric vector field, but nevertheless an emf does work that can be measured as a virtual electric potential around that loop.[4] In a two-terminal device (such as an electrochemical cell or electromagnetic generator), the emf can be measured as the open-circuit potential difference across the two terminals. The potential difference thus created drives current flow if an external circuit is attached to the source of emf. When current flows, however, the potential difference across the terminals is no longer equal to the emf, but will be smaller because of the voltage drop within the device due to its internal resistance. Devices that can provide emf includeelectrochemical cells, thermoelectric devices, solar cells and photodiodes, electrical generators,transformers, and even Van de Graaff generators.[4][5] In nature, emf is generated whenever magnetic field fluctuations occur through a surface. -

Maxwell's Equations

Maxwell’s Equations Matt Hansen May 20, 2004 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 The basics 3 2.1 Static charges . 3 2.2 Moving charges . 4 2.3 Magnetism . 4 2.4 Vector operations . 5 2.5 Calculus . 6 2.6 Flux . 6 3 History 7 4 Maxwell’s Equations 8 4.1 Maxwell’s Equations . 8 4.2 Gauss’ law for electricity . 8 4.3 Gauss’ law for magnetism . 10 4.4 Faraday’s law . 11 4.5 Ampere-Maxwell law . 13 5 Conclusion 14 2 1 Introduction If asked, most people outside a physics department would not be able to identify Maxwell’s equations, nor would they be able to state that they dealt with electricity and magnetism. However, Maxwell’s equations have many very important implications in the life of a modern person, so much so that people use devices that function off the principles in Maxwell’s equations every day without even knowing it. 2 The basics 2.1 Static charges In order to understand Maxwell’s equations, it is necessary to understand some basic things about electricity and magnetism first. Static electricity is easy to understand, in that it is just a charge which, as its name implies, does not move until it is given the chance to “escape” to the ground. Amounts of charge are measured in coulombs, abbreviated C. 1C is an extraordi- nary amount of charge, chosen rather arbitrarily to be the charge carried by 6.41418 · 1018 electrons. The symbol for charge in equations is q, sometimes with a subscript like q1 or qenc. -

Electro Magnetic Fields Lecture Notes B.Tech

ELECTRO MAGNETIC FIELDS LECTURE NOTES B.TECH (II YEAR – I SEM) (2019-20) Prepared by: M.KUMARA SWAMY., Asst.Prof Department of Electrical & Electronics Engineering MALLA REDDY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY (Autonomous Institution – UGC, Govt. of India) Recognized under 2(f) and 12 (B) of UGC ACT 1956 (Affiliated to JNTUH, Hyderabad, Approved by AICTE - Accredited by NBA & NAAC – ‘A’ Grade - ISO 9001:2015 Certified) Maisammaguda, Dhulapally (Post Via. Kompally), Secunderabad – 500100, Telangana State, India ELECTRO MAGNETIC FIELDS Objectives: • To introduce the concepts of electric field, magnetic field. • Applications of electric and magnetic fields in the development of the theory for power transmission lines and electrical machines. UNIT – I Electrostatics: Electrostatic Fields – Coulomb’s Law – Electric Field Intensity (EFI) – EFI due to a line and a surface charge – Work done in moving a point charge in an electrostatic field – Electric Potential – Properties of potential function – Potential gradient – Gauss’s law – Application of Gauss’s Law – Maxwell’s first law, div ( D )=ρv – Laplace’s and Poison’s equations . Electric dipole – Dipole moment – potential and EFI due to an electric dipole. UNIT – II Dielectrics & Capacitance: Behavior of conductors in an electric field – Conductors and Insulators – Electric field inside a dielectric material – polarization – Dielectric – Conductor and Dielectric – Dielectric boundary conditions – Capacitance – Capacitance of parallel plates – spherical co‐axial capacitors. Current density – conduction and Convection current densities – Ohm’s law in point form – Equation of continuity UNIT – III Magneto Statics: Static magnetic fields – Biot‐Savart’s law – Magnetic field intensity (MFI) – MFI due to a straight current carrying filament – MFI due to circular, square and solenoid current Carrying wire – Relation between magnetic flux and magnetic flux density – Maxwell’s second Equation, div(B)=0, Ampere’s Law & Applications: Ampere’s circuital law and its applications viz. -

Measuring Electricity Voltage Current Voltage Current

Measuring Electricity Electricity makes our lives easier, but it can seem like a mysterious force. Measuring electricity is confusing because we cannot see it. We are familiar with terms such as watt, volt, and amp, but we do not have a clear understanding of these terms. We buy a 60-watt lightbulb, a tool that needs 120 volts, or a vacuum cleaner that uses 8.8 amps, and dont think about what those units mean. Using the flow of water as an analogy can make Voltage electricity easier to understand. The flow of electrons in a circuit is similar to water flowing through a hose. If you could look into a hose at a given point, you would see a certain amount of water passing that point each second. The amount of water depends on how much pressure is being applied how hard the water is being pushed. It also depends on the diameter of the hose. The harder the pressure and the larger the diameter of the hose, the more water passes each second. The flow of electrons through a wire depends on the electrical pressure pushing the electrons and on the Current cross-sectional area of the wire. The flow of electrons can be compared to the flow of Voltage water. The water current is the number of molecules flowing past a fixed point; electrical current is the The pressure that pushes electrons in a circuit is number of electrons flowing past a fixed point. called voltage. Using the water analogy, if a tank of Electrical current (I) is defined as electrons flowing water were suspended one meter above the ground between two points having a difference in voltage. -

Calculating Electric Power

Calculating electric power We've seen the formula for determining the power in an electric circuit: by multiplying the voltage in "volts" by the current in "amps" we arrive at an answer in "watts." Let's apply this to a circuit example: In the above circuit, we know we have a battery voltage of 18 volts and a lamp resistance of 3 Ω. Using Ohm's Law to determine current, we get: Now that we know the current, we can take that value and multiply it by the voltage to determine power: Answer: the lamp is dissipating (releasing) 108 watts of power, most likely in the form of both light and heat. Let's try taking that same circuit and increasing the battery voltage to see what happens. Intuition should tell us that the circuit current will increase as the voltage increases and the lamp resistance stays the same. Likewise, the power will increase as well: Now, the battery voltage is 36 volts instead of 18 volts. The lamp is still providing 3 Ω of electrical resistance to the flow of electrons. The current is now: This stands to reason: if I = E/R, and we double E while R stays the same, the current should double. Indeed, it has: we now have 12 amps of current instead of 6. Now, what about power? Notice that the power has increased just as we might have suspected, but it increased quite a bit more than the current. Why is this? Because power is a function of voltage multiplied by current, and both voltage and current doubled from their previous values, the power will increase by a factor of 2 x 2, or 4. -

Electromotive Force

Voltage - Electromotive Force Electrical current flow is the movement of electrons through conductors. But why would the electrons want to move? Electrons move because they get pushed by some external force. There are several energy sources that can force electrons to move. Chemical: Battery Magnetic: Generator Light (Photons): Solar Cell Mechanical: Phonograph pickup, crystal microphone, antiknock sensor Heat: Thermocouple Voltage is the amount of push or pressure that is being applied to the electrons. It is analogous to water pressure. With higher water pressure, more water is forced through a pipe in a given time. With higher voltage, more electrons are pushed through a wire in a given time. If a hose is connected between two faucets with the same pressure, no water flows. For water to flow through the hose, it is necessary to have a difference in water pressure (measured in psi) between the two ends. In the same way, For electrical current to flow in a wire, it is necessary to have a difference in electrical potential (measured in volts) between the two ends of the wire. A battery is an energy source that provides an electrical difference of potential that is capable of forcing electrons through an electrical circuit. We can measure the potential between its two terminals with a voltmeter. Water Tank High Pressure _ e r u e s g s a e t r l Pump p o + v = = t h g i e h No Pressure Figure 1: A Voltage Source Water Analogy. In any case, electrostatic force actually moves the electrons. -

Electromagnetic Induction, Ac Circuits, and Electrical Technologies 813

CHAPTER 23 | ELECTROMAGNETIC INDUCTION, AC CIRCUITS, AND ELECTRICAL TECHNOLOGIES 813 23 ELECTROMAGNETIC INDUCTION, AC CIRCUITS, AND ELECTRICAL TECHNOLOGIES Figure 23.1 This wind turbine in the Thames Estuary in the UK is an example of induction at work. Wind pushes the blades of the turbine, spinning a shaft attached to magnets. The magnets spin around a conductive coil, inducing an electric current in the coil, and eventually feeding the electrical grid. (credit: phault, Flickr) 814 CHAPTER 23 | ELECTROMAGNETIC INDUCTION, AC CIRCUITS, AND ELECTRICAL TECHNOLOGIES Learning Objectives 23.1. Induced Emf and Magnetic Flux • Calculate the flux of a uniform magnetic field through a loop of arbitrary orientation. • Describe methods to produce an electromotive force (emf) with a magnetic field or magnet and a loop of wire. 23.2. Faraday’s Law of Induction: Lenz’s Law • Calculate emf, current, and magnetic fields using Faraday’s Law. • Explain the physical results of Lenz’s Law 23.3. Motional Emf • Calculate emf, force, magnetic field, and work due to the motion of an object in a magnetic field. 23.4. Eddy Currents and Magnetic Damping • Explain the magnitude and direction of an induced eddy current, and the effect this will have on the object it is induced in. • Describe several applications of magnetic damping. 23.5. Electric Generators • Calculate the emf induced in a generator. • Calculate the peak emf which can be induced in a particular generator system. 23.6. Back Emf • Explain what back emf is and how it is induced. 23.7. Transformers • Explain how a transformer works. • Calculate voltage, current, and/or number of turns given the other quantities. -

2 Classical Field Theory

2 Classical Field Theory In what follows we will consider rather general field theories. The only guiding principles that we will use in constructing these theories are (a) symmetries and (b) a generalized Least Action Principle. 2.1 Relativistic Invariance Before we saw three examples of relativistic wave equations. They are Maxwell’s equations for classical electromagnetism, the Klein-Gordon and Dirac equations. Maxwell’s equations govern the dynamics of a vector field, the vector potentials Aµ(x) = (A0, A~), whereas the Klein-Gordon equation describes excitations of a scalar field φ(x) and the Dirac equation governs the behavior of the four- component spinor field ψα(x)(α =0, 1, 2, 3). Each one of these fields transforms in a very definite way under the group of Lorentz transformations, the Lorentz group. The Lorentz group is defined as a group of linear transformations Λ of Minkowski space-time onto itself Λ : such that M M→M ′µ µ ν x =Λν x (1) The space-time components of Λ are the Lorentz boosts which relate inertial reference frames moving at relative velocity ~v. Thus, Lorentz boosts along the x1-axis have the familiar form x0 + vx1/c x0′ = 1 v2/c2 − x1 + vx0/c x1′ = p 1 v2/c2 − 2′ 2 x = xp x3′ = x3 (2) where x0 = ct, x1 = x, x2 = y and x3 = z (note: these are components, not powers!). If we use the notation γ = (1 v2/c2)−1/2 cosh α, we can write the Lorentz boost as a matrix: − ≡ x0′ cosh α sinh α 0 0 x0 x1′ sinh α cosh α 0 0 x1 = (3) x2′ 0 0 10 x2 x3′ 0 0 01 x3 The space components of Λ are conventional three-dimensional rotations R. -

Chapter 2. Electrostatics

Chapter 2. Electrostatics Introduction to Electrodynamics, 3rd or 4rd Edition, David J. Griffiths 2.3 Electric Potential 2.3.1 Introduction to Potential We're going to reduce a vector problem (finding E from E 0 ) down to a much simpler scalar problem. E 0 the line integral of E from point a to point b is the same for all paths (independent of path) Because the line integral of E is independent of path, we can define a function called the Electric Potential: : O is some standard reference point The potential difference between two points a and b is The fundamental theorem for gradients states that The electric field is the gradient of scalar potential 2.3.2 Comments on Potential (i) The name. “Potential" and “Potential Energy" are completely different terms and should, by all rights, have different names. There is a connection between "potential" and "potential energy“: Ex: (ii) Advantage of the potential formulation. “If you know V, you can easily get E” by just taking the gradient: This is quite extraordinary: One can get a vector quantity E (three components) from a scalar V (one component)! How can one function possibly contain all the information that three independent functions carry? The answer is that the three components of E are not really independent. E 0 Therefore, E is a very special kind of vector: whose curl is always zero Comments on Potential (iii) The reference point O. The choice of reference point 0 was arbitrary “ambiguity in definition” Changing reference points amounts to adding a constant K to the potential: Adding a constant to V will not affect the potential difference: since the added constants cancel out.