Key Ingredients Exhibition Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

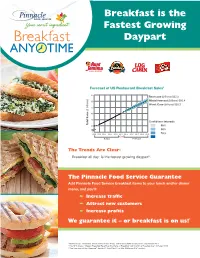

Breakfast Is the Fastest Growing Daypart

BreakfastBreakfast isis thethe FastestFastest GrowingGrowing DaypartDaypart Forecast of US Restaurant Breakfast Sales1 65 Best case (billions) $82.5 60 Mintel forecast (billions) $60.4 Worst Case (billions) $58.3 55 ($ billions) 50 45 Confi dence intervals Total Sales Total 40 95% 90% 0 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 70% Est. Actual Forecast The Trends Are Clear: • • Breakfast all day1 is the fastest growing daypart2. The Pinnacle Food Service Guarantee Add Pinnacle Food Service breakfast items to your lunch and/or dinner menu, and you’ll: ➨ Increase traffic ➨ Attract new customers ➨ Increase profits We guarantee it – or breakfast is on us!3 1 Mintel Group, “Breakfast Trends at Home and Away: The Morning Meal at Any Time”, September 2015 2 The NPD Group, “Classic Breakfast Fare Ride the Wave of Breakfast Visit Growth at Foodservice”, October 2015 3 One free case of Aunt Jemima®, Lender’s®, Log Cabin®, or Mrs. Butterworth’s® product. Breakfast Anytime Program Elements Here are all the tools you’ll need to serve Breakfast Anytime! • Menu Idea Guide – Recipes and menu ideas for breakfast and beyond. Menu Contest Get Creative and Get Rewarded - Enter the Breakfast Anytime Menu Contest! Menu Contest Grand • – Share your menu ideas and Prize $1,000 for You AND Peaches & Cream $1,000 for Your Local Food Bank! Stuffed French Toast* PLUS: 15 MORE CHANCES TO WIN! get a free case of product just for entering. 3 WINNERS FROM EACH OF 5 REGIONS – 1ST PRIZE: $500, 2ND PRIZE: $300, 3RD PRIZE: $200 See website for region map. -

Auction Catalog Lot# Description

Auction Catalog Lot# Description 1 8 BOX LOTS OF COCA COLA ITEMS 2 STACK OF METAL COCA COLA TRAYS 3 TUB OF COCA COLA TOYS 4 LOT OF MODERN SHADOWBOXES 5 ANTIQUE COIN OP. "PEERLESS" LOLLIPOP SCALE 6 WOODEN "ANTIQUES" SIGN 7 2 ORANGE CRUSH PORCELAIN SIGNS 8 VENDO 39B COCA COLA MACHINE 9 BARNUM & BAILEY CIRCUS POSTER 10 COCA COLA ELECTRIC CLOCK 11 1930 COCA COLA TRAY 12 2 DUKE & CARLINGS BEER SIGNS 13 LARGE LOT OF LEAD SOLDIERS & BREYER HORSES 14 EXCELSIOR BUTTERMILK COUNTER DISPENSER (SANTA ANA) 15 EXCELSIOR DIE CUT TIN MILK SIGN (SANTA ANA) 16 LOT OF MISC. EXCELSIOR DAIRY ITEMS (SANTA ANA) 17 2 COCA COLA HOLDERS W/ BOTTLES 18 BLUE JAY CORN PLASTERS TIN LITHO STORE DISPLAY 19 SMITH DOUGLAS FERTILIZER DOOR PUSH 20 HEADS UP FOUL BALL TIN SIGN 21 PUTNAME DYE COUNTER TOP CABINET 22 LOT OF ANTIQUE TOOLS INC.: INDIAN, NASH, CADILLAC, & MORE 23 QUAKER STATE THERMOMETER & CHATTANOGA TIMES THERMOMETER 24 SMITH BROS COUGH DROP COUNTER DISPLAY 25 WRIGLEY'S GUM COUNTER TOP DISPLAY 26 SCHLITZ ADVERTISING BEER MUG 27 COORS MALTED MILK JAR 28 3 PORCELAIN SHOPPING CART SIGNS 29 WESTERN UNION PORCELAIN SIGN 30 POSTAGE STAMP MACHINE 31 VINTAGE PAY PHONE 32 2 TOY TRUCKS 33 FORD TOOL BOX W/ FORD TOOLS 34 PEDAL CAR BARBER CHAIR (RESTORED) 35 NATIONAL BRASS CANDY STORE CASH REGISTER 36 1950'S COIN MOTEL RADIO 37 JAPANESE TIN LITHO FRICTION MOTORCYCLE 38 PR. TROLLEY PORCELAIN "CAR STOP" PENNANT SIGNS 39 SMALL HIRES TIN SIGN & HIRES CARDBOARD SIGN Lo40t# AMOS & ADNeDsYcr TipINtio LnITHO TAXI 41 ROCK ISLAND RAILROAD OILER 42 ALAMEDA COUNTY TRANSIT PORCELAIN SIGN -

Chopsticks Is a Divine Art of Chinese Culture

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 2, Issue - 11, Nov – 2018 Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Impact Factor: 4.526 Publication Date: 30/11/2018 Chopsticks is a Divine Art of Chinese Culture Md. Abu Naim Shorkar School of Economics, Shanghai University, 99, Shangda Road, Shanghai, China, 200444, Email – [email protected] Abstract: Chopsticks are the primary eating instrument in Chinese culture, and every youngster has to adopt using technique and controlling of chopsticks. A couple of chopsticks is the main instrument for eating, and the physical movements of control are familiar with Chinese. The Chinese use chopsticks as natural as Caucasians use knives and forks. An analogy of chopsticks is as an extension of one’s fingers. Chinese food is prepared so that it may be easily handled with chopsticks. In fact, many traditional Chinese families do not have forks at home. The usage of chopsticks has been deeply mixed into Chinese culture. In any occasions, food has become a cultural show in today’s society. When food from single nation becomes in another, it leads to a sort of cultural interchange. China delivers a deep tradition of food culture which has spread around the globe. As a company rises, food culture too evolves resulting in mutations. Each geographical location makes its own food with unparalleled taste and smell. Sullen, sweet, bitter and hot are the preferences of several food items. Apart from being good, they tell us about the people who make it, their culture and nation. The creatures which people apply to eat are not only creatures, but also symbols, relics of that civilization. -

Korean Food and American Food by Yangsook

Ahn 1 Yangsook Ahn Instructor’s Name ENGL 1013 Date Korean Food and American Food Food is a part of every country’s culture. For example, people in both Korea and America cook and serve traditional foods on their national holidays. Koreans eat ddukguk, rice cake soup, on New Year’s Day to celebrate the beginning of a new year. Americans eat turkey on Thanksgiving Day. Although observing national holidays is a similarity between their food cultures, Korean food culture differs from American food culture in terms of utensils and appliances, ingredients and cooking methods, and serving and dining manners. The first difference is in utensils and appliances. Koreans’ eating utensils are a spoon and chopsticks. Koreans mainly use chopsticks and ladles to cook side dishes and soups; also, scissors are used to cut meats and other vegetables, like kimchi. Korean food is based on rice; therefore, a rice cooker is an important appliance. Another important appliance in Korean food culture is a kimchi refrigerator. Koreans eat many fermented foods, like kimchi, soybean paste, and red chili paste. For this reason, almost every Korean household has a kimchi refrigerator, which is designed specifically to meet the storage requirements of kimchi and facilitate different fermentation processes. While Koreans use a spoon and chopsticks, Americans use a fork and a knife as main eating utensils. Americans use various cooking utensils like a spatula, tongs, spoon, whisk, peeler, and measuring cups. In addition, the main appliance for American food is an oven since American food is based on bread. A fryer, toaster, and blender are also important equipment to Ahn 2 prepare American foods. -

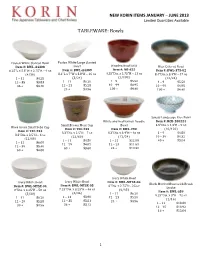

2013.01-06 New Korin Items

NEW$KORIN$ITEMS$JANUARY$–$JUNE$2013$ Limited'Quantities'Available' ' TABLEWARE:"Bowls" " " " Fusion"White"Slanted"Bowl" Fusion"White"Large"Slanted" " " Item%#:%BWL+A4308% Bowl" Wooden"Bowl"RED" Blue"Colored"Bowl" 6.25"L"x"5.5"W"x"2.75"H"–"9"oz" Item%#:%BWL+A4309% Item%#:%NR+625% Item%#:%BWL+375+02% (4/36)" 8.1”L"x"7”W"x"3.8"H"–"16"oz" 4.25"Dia."x"2.75"H"–"11"oz" 8.4"Dia."x"3.4"H"–"47"oz" 1"–"11" $4.25" (3/24)" (1/100)" (12/24)" 12"–"35" $3.83" 1"–"11" $6.20" 1"–"9" $5.50" 1"–"9" $5.50" 36"+" $3.40" 12"–"23" $5.58" 10"–"99" $4.95" 10"–"99" $4.95" " " 24"+" $4.96" 100"+" $4.40" 100"+" $4.40" " " " " " " " " " " " " Sansui"Landscape"Rice"Bowl" " White"and"Red"Ramen"Noodle" Item%#:%RCB+200224% " Small"Brown"Moss"Cup" Bowl" 4.5"Dia."x"1.3"H"–"9"oz" Hiwa"Green"Small"Soba"Cup" Item%#:%TEC+233% Item%#:%BWL+290% (10/120)" Item%#:%TEC+234% 3.3”Dia."x"2.5"H"–"7"oz" 8.3”Dia."x"3.4"H"–"46"oz" 1"–"9" $4.80" 3.3”Dia."x"2.5"H"–"6"oz" (12/60)" (12/24)" 10"–"39" $4.32" (12/60)" 1"–"11" $4.50" 1"–"11" $12.90" 40"+" $3.84" 1"–"11" $6.00" " " 12"–"59" $4.05" 12"–"23" $11.61" " 12"–"59" $5.40" 60"+" $3.60" 24"+" $10.32" 60"+" $4.80" " " " " " " Ivory"White"Bowl" Ivory"White"Bowl" Item%#:%BWL+MTSX+06% " Ivory"White"Bowl" Black"Mottled"Bowl"with"Brush" Item%#:%BWL+MTSX+05% 6"Dia."x"2.75"H"\"25"oz" Item%#:%BWL+MTSX+04% Stroke" 7.25"Dia."x"3.25"H"–"46"oz" (6/48)" 8"Dia."x"3.25"H"–"58"oz" Item%#:%BWL+S59% (6/36)" 1"–"11" $6.20" (5/30)" 9.25"Dia."x"3"H"–"72"oz" 1"–"11" $3.90" 12"–"23" $5.58" 1"–"11" $6.20" (1/16)" 12"–"35" $3.51" 24"+" $4.96" 12"–"29" $5.58" 1"–"11" -

Kenmore Elite® Slide-In Electric Range Estufa a Inducción Deslizable * = Color Number, Numéro De Color

Use & Care Guide Manual de Uso y Cuidado English / Español Model/Modelo: 790.4262* Kenmore Elite® Slide-in Electric Range Estufa a Inducción Deslizable * = color number, numéro de color P/N 139900700 Rev. A Sears Brands Management Corporation Hoffman Estates, IL 60179 U.S.A. www.kenmore.com www.sears.com Setting Oven Controls ............................................................................... 17 Table of Contents Care and Cleaning ..................................................................................... 35 Before Setting Surface Controls .................................................................. 8 Before You Call ........................................................................................... 40 Setting Surface Controls............................................................................. 13 Oven Baking .............................................................................................40 Before Setting Oven Controls ................................................................... 15 Solutions to Common Problems ..............................................................41 Kenmore Elite Warranty When this appliance is installed, operated and maintained according to all supplied instructions, the following warranty coverage applies. To arrange for warranty service, call 1-800-4-MY-HOME® (1-800-469-4663). U.S.A. Warranty Coverage · One Year Limited Warranty on Appliance For one year from the date of purchase, free repair will be provided if this appliance fails due to a defect -

Spilyay Tymoo, Vol. 39, No. 14, Jul. 09, 2014

P.O. Box 870 Warm Springs, OR 97761 ECR WSS Postal Patron SpilyaySpilyaySpilyay TymooTymooTymoo U.S. Postage PRSRT STD July 9, 2014 Vol. 39, No. 14 Warm Springs, OR 97761 Coyote News, est. 1976 July – Pat’ak-Pt’akni – Summer - Shatm 50 cents Mill Creek restoration under way School Update Construction crews are moving Construction tons of earth in the area of Potter’s Ponds on Mill Creek. wrapping up This is a large-scale fisheries im- provement project, similar to but big- next week ger than the 2009 Shitike Creek im- provement project. A week from Friday will mark a The Bonneville Power Adminis- milestone for the Confederated tration is funding much of the work, Tribes. Friday, July 18 will be the as a mitigation project, with over- substantial completion day for the sight by the tribal Natural Resources Warm Springs k-8 Academy, mean- Branch. Scott Turo, fisheries biolo- ing the school will be ready for oc- gist, and Johnny Holliday, project co- cupancy. ordinator, are on site daily. After that date, tribal and school The contractor for the project is district officials can tour the facili- BCI Contracting, based in Portland. ties, making any suggestions as to The company focuses on wetland final construction details. and stream restoration projects. “We’ll be on site until the end of Business co-owner and operator the month, but we should have the Drew Porter said any tribal mem- certificate of occupancy by July ber with heavy machinery creden- 18,” said Jason Terry, school project Dave McMechan/Spilyay photos tials is invited contact him about Scott Turo and Johnny Holliday, of Natural Resources, with contractor Drew Porter by the Mill manager, with Kirby Nagelhout work opportunities. -

“Unlimited” Tolerance in Linguoculture

Armenian Folia Anglistika Culture On Some Forms of “Out-Group” Intolerance and “Unlimited” Tolerance in Linguoculture Narine Harutyunyan Yerevan State University Abstract The subject of the research is ethnic intolerance as a form of relationship between “we” and “other”, manifested in various modifications of the hostility towards others. There are several main types of ethno-intolerant relations: ethnocentrism; xenophobia, migrant phobia, etc. The author's definitions of such concepts as “intercultural whirlpool”, “ethnocentric craters” and “xenophobic craters”, “emotional turbulence of communication” are presented. The negative, discreditable signs of ethnicity of a particular national community are represented in the lexical units of English in such a way as if the “other” ethnic group has the shortcomings that are not in the “we” group. The problem of “unlimited” tolerance is considered when “strangers” – immigrants, seek to impose “their own” religious and cultural traditions, worldview and psychological dominant on local people. The article deals with the problems of intolerance and “unlimited” tolerance not only as complex socio-psychological, but also as linguocultural phenomena that are actualized in the linguistic consciousness of the ethnic group (English-speaking groups, in particular). The article also deals with the problem of “aggressive” expansion of the English language, which destroys the nation’s value system, distorts its language habits and perception of the surrounding reality, and creates discriminatory dominance of a certain linguoculture. Key words: ethnocentrism, xenophobia, migrant phobia, tolerance, linguistic hegemony. 130 Culture Armenian Folia Anglistika Introduction In the 21st century, the relevance of language learning in conjunction with extralinguistic factors has significantly increased, since the world today is multi-polar and multicultural. -

FCP Foundation Provides Grant for Revolving Loan Fund Initiative Submitted by Forest County Economic Development Partnership in This Issue

www.fcpotawatomi.com • [email protected] • 715-478-7437 • FREE POTAWATOMI TRAVELING TIMES VOLUME 18, ISSUE 16 MKO GISOS LITTLE BEAR MONTH FEBRUARY 15, 2013 FCP Foundation Provides Grant for Revolving Loan Fund Initiative submitted by Forest County Economic Development Partnership In this Issue: Pokagon Band Language Interns pg. 4 Devil’s Lake Fisheree Results pgs. 7, 8 Pictured are (l-r): FCP Executive Council Treasurer Richard Gougé III, FCEDP Executive Director Jim Schuessler and FCP Executive Council Member Nate Gilpin, Jr. Calendar ..........pg. 11 CRANDON, Wis. - The Forest citizenship by assisting charitable organ- being developed; applications will not Notices ......pg. 10, 11 County Potawatomi (FCP) Foundation izations. This revolving loan fund offers be solicited until later this spring. “Local Personals ..........pg. 11 announced a grant for the Forest County the potential to help continue to deliver lenders are still the primary way to Economic Development Partnership upon those ideals.” advance business plans,” added (FCEDP) Revolving Loan Fund. The “The Foundation was instrumental Schuessler. “A revolving loan fund is Foundation announced a $25,000 invest- in putting a full-time economic develop- another tool in the economic develop- ment to the fund to help establish a ment effort program in the county,” said ment tool chest we will be able to use revolving loan fund in Forest County. FCEDP Executive Director Jim here going forward.” Announced late last fall, the fund will Schuessler. “This grant will help launch One of the goals of the fund will be operate as a micro-loan fund designed to new business opportunity right here. -

Burgoo Saddler Taylor University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Staff ubP lications McKissick Museum 2007 Burgoo Saddler Taylor University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/mks_staffpub Part of the History Commons Publication Info Published in New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture - Foodways (Volume 7), ed. John T. Edge, 2007, pages 132-133. http://www.uncpress.unc.edu/browse/book_detail?title_id=1192 © 2007 by University of North Carolina Press Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. This Article is brought to you by the McKissick Museum at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. sian of munon is the major difference between burgoo and Brunswick stew. Otherwise, the nyo stews are quite similar, in both preparation and con sumption. While western Kentucky burgoo recipes are distinguished by this critical difference, many of them actually in clude other meats as wel l. Some recipes call for squirrel, veal, oxtail, or pork, bringing to mind jokes told by stew masters that refer to «possum or animals that got too close to the paLM Ihe story telling and banter during the long hours of stew preparation are keys to strong social bonds that develop over a period of time. Kentuckians tell stories about the legendary Gus Jaubert, a member of Morgan's Raiders during the Civil War, who supposedly prepared hundreds of gallons of the spicy hunter's stew for the general's men. -

October 2010.Pub

Issue # 33 October 2010 Central Illinois Teaching with Primary Sources Newsletter EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY EDWARDSVILLE The Secret Ingredient: Recipes INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Topic Introduction 2 Connecting to Illinois 3 Close to Home 3 Learn More with 4 American Memory In The Classroom 6 Test Your Knowledge 8 Image Sources 9 CONTACTS • Melissa Carr [email protected] Editor • Cindy Rich [email protected] • Amy Wilkinson [email protected] eiu.edu/~eiutps/newsletter Page 2 Recipes Secret Ingredient Welcome to the Central Illinois Teaching with Primary Although Simmons borrowed many of the recipes from Sources Newsletter a collaborative project of Teaching British cookbooks, she added her own twist by including with Primary Sources Programs at Eastern Illinois ingredients native to America such as corn meal. University and Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Recipes can be much more than ingredients and Our goal is to bring you topics that connect to the Illinois measurements, they are a primary source offering a Learning Standards as well as provide you will amazing glimpse into a family’s history. You may have a recipe, items from the Library of Congress. Recipes are tattered from being folded and unfolded again and again mentioned specifically within ISBE materials for the over generations. Aside from creating a delicious dish, following Illinois Learning Standards (found within goal, this recipe can show a family’s identity through culture, standard, benchmark or performance descriptors), 3- tradition or religious significance. Ingredients may have Write to communicate for a variety of purposes. 6- been added or changed over Demonstrate and apply a knowledge and sense of the years depending on the Recipes can be much numbers, including numeration and operations (addition, items available in the subtractions, multiplication, more than ingredients region. -

The Fruits of Empire: Contextualizing Food in Post-Civil War American Art and Culture

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Art & Art History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2015 The rF uits of Empire: Contextualizing Food in Post-Civil War American Art and Culture Shana Klein Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/arth_etds Recommended Citation Klein, Shana. "The rF uits of Empire: Contextualizing Food in Post-Civil War American Art and Culture." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/arth_etds/6 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art & Art History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Shana Klein Candidate Art and Art History Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Kirsten Buick , Chairperson Dr. Catherine Zuromskis Dr. Kymberly Pinder Dr. Katharina Vester ii The Fruits of Empire: Contextualizing Food in Post-Civil War American Art and Culture by Shana Klein B.A., Art History, Washington University in Saint Louis M.A., Art History, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque Ph.D., Art History, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2015 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to acknowledge the bottomless amounts of support I received from my advisor, Dr. Kirsten Buick. Dr. Buick gave me the confidence to pursue the subject of food in art, which at first seemed quirky and unusual to many.