Chopsticks and the Land of the Five Flavors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chopsticks Is a Divine Art of Chinese Culture

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 2, Issue - 11, Nov – 2018 Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Impact Factor: 4.526 Publication Date: 30/11/2018 Chopsticks is a Divine Art of Chinese Culture Md. Abu Naim Shorkar School of Economics, Shanghai University, 99, Shangda Road, Shanghai, China, 200444, Email – [email protected] Abstract: Chopsticks are the primary eating instrument in Chinese culture, and every youngster has to adopt using technique and controlling of chopsticks. A couple of chopsticks is the main instrument for eating, and the physical movements of control are familiar with Chinese. The Chinese use chopsticks as natural as Caucasians use knives and forks. An analogy of chopsticks is as an extension of one’s fingers. Chinese food is prepared so that it may be easily handled with chopsticks. In fact, many traditional Chinese families do not have forks at home. The usage of chopsticks has been deeply mixed into Chinese culture. In any occasions, food has become a cultural show in today’s society. When food from single nation becomes in another, it leads to a sort of cultural interchange. China delivers a deep tradition of food culture which has spread around the globe. As a company rises, food culture too evolves resulting in mutations. Each geographical location makes its own food with unparalleled taste and smell. Sullen, sweet, bitter and hot are the preferences of several food items. Apart from being good, they tell us about the people who make it, their culture and nation. The creatures which people apply to eat are not only creatures, but also symbols, relics of that civilization. -

Korean Food and American Food by Yangsook

Ahn 1 Yangsook Ahn Instructor’s Name ENGL 1013 Date Korean Food and American Food Food is a part of every country’s culture. For example, people in both Korea and America cook and serve traditional foods on their national holidays. Koreans eat ddukguk, rice cake soup, on New Year’s Day to celebrate the beginning of a new year. Americans eat turkey on Thanksgiving Day. Although observing national holidays is a similarity between their food cultures, Korean food culture differs from American food culture in terms of utensils and appliances, ingredients and cooking methods, and serving and dining manners. The first difference is in utensils and appliances. Koreans’ eating utensils are a spoon and chopsticks. Koreans mainly use chopsticks and ladles to cook side dishes and soups; also, scissors are used to cut meats and other vegetables, like kimchi. Korean food is based on rice; therefore, a rice cooker is an important appliance. Another important appliance in Korean food culture is a kimchi refrigerator. Koreans eat many fermented foods, like kimchi, soybean paste, and red chili paste. For this reason, almost every Korean household has a kimchi refrigerator, which is designed specifically to meet the storage requirements of kimchi and facilitate different fermentation processes. While Koreans use a spoon and chopsticks, Americans use a fork and a knife as main eating utensils. Americans use various cooking utensils like a spatula, tongs, spoon, whisk, peeler, and measuring cups. In addition, the main appliance for American food is an oven since American food is based on bread. A fryer, toaster, and blender are also important equipment to Ahn 2 prepare American foods. -

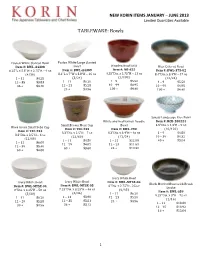

2013.01-06 New Korin Items

NEW$KORIN$ITEMS$JANUARY$–$JUNE$2013$ Limited'Quantities'Available' ' TABLEWARE:"Bowls" " " " Fusion"White"Slanted"Bowl" Fusion"White"Large"Slanted" " " Item%#:%BWL+A4308% Bowl" Wooden"Bowl"RED" Blue"Colored"Bowl" 6.25"L"x"5.5"W"x"2.75"H"–"9"oz" Item%#:%BWL+A4309% Item%#:%NR+625% Item%#:%BWL+375+02% (4/36)" 8.1”L"x"7”W"x"3.8"H"–"16"oz" 4.25"Dia."x"2.75"H"–"11"oz" 8.4"Dia."x"3.4"H"–"47"oz" 1"–"11" $4.25" (3/24)" (1/100)" (12/24)" 12"–"35" $3.83" 1"–"11" $6.20" 1"–"9" $5.50" 1"–"9" $5.50" 36"+" $3.40" 12"–"23" $5.58" 10"–"99" $4.95" 10"–"99" $4.95" " " 24"+" $4.96" 100"+" $4.40" 100"+" $4.40" " " " " " " " " " " " " Sansui"Landscape"Rice"Bowl" " White"and"Red"Ramen"Noodle" Item%#:%RCB+200224% " Small"Brown"Moss"Cup" Bowl" 4.5"Dia."x"1.3"H"–"9"oz" Hiwa"Green"Small"Soba"Cup" Item%#:%TEC+233% Item%#:%BWL+290% (10/120)" Item%#:%TEC+234% 3.3”Dia."x"2.5"H"–"7"oz" 8.3”Dia."x"3.4"H"–"46"oz" 1"–"9" $4.80" 3.3”Dia."x"2.5"H"–"6"oz" (12/60)" (12/24)" 10"–"39" $4.32" (12/60)" 1"–"11" $4.50" 1"–"11" $12.90" 40"+" $3.84" 1"–"11" $6.00" " " 12"–"59" $4.05" 12"–"23" $11.61" " 12"–"59" $5.40" 60"+" $3.60" 24"+" $10.32" 60"+" $4.80" " " " " " " Ivory"White"Bowl" Ivory"White"Bowl" Item%#:%BWL+MTSX+06% " Ivory"White"Bowl" Black"Mottled"Bowl"with"Brush" Item%#:%BWL+MTSX+05% 6"Dia."x"2.75"H"\"25"oz" Item%#:%BWL+MTSX+04% Stroke" 7.25"Dia."x"3.25"H"–"46"oz" (6/48)" 8"Dia."x"3.25"H"–"58"oz" Item%#:%BWL+S59% (6/36)" 1"–"11" $6.20" (5/30)" 9.25"Dia."x"3"H"–"72"oz" 1"–"11" $3.90" 12"–"23" $5.58" 1"–"11" $6.20" (1/16)" 12"–"35" $3.51" 24"+" $4.96" 12"–"29" $5.58" 1"–"11" -

Chopsticks: a Chinese Invention 507 Sopris West Six Minute Solutions Passage

Curriculum-Based Measurement: Maze Passage: Examiner Copy Student/Classroom: _____________________ Examiner: ____________ Assessment Date: _______ Chopsticks: A Chinese Invention 507 Sopris West Six Minute Solutions Passage Chopsticks were invented in China more than 5,000 years ago. Long ago, food was chopped into (little) pieces so it would cook faster. (The) faster food cooked, the more fuel (it) would save. Since food was eaten (in) small pieces, there was no need (for) knives. Rather, chopsticks were used to (move) food from the plate to the (mouth). Confucius was a Chinese philosopher. He (was) a vegetarian. It is believed that (Confucius) did not like knives. Knives reminded (him) of the slaughterhouse. He favored chopsticks. (By) A.D.500, the use of chopsticks (had) spread to other countries. The people (in) present day Vietnam, Korea, and Japan, (as) well as China, use chopsticks today. (Chinese) chopsticks are about 9 or 10 inches long. (They) are square at the top, have (a) blunt end, and are thinner on (the) bottom. The Chinese call them kuai-ai. (This) means "quick little fellows." Chopsticks have (been) made of many materials. Bamboo is (a) popular choice since it is available, (and) inexpensive. Bamboo is also heat resistant. (Other) types of wood such as sandalwood, (cedar), and teak have also been used. (Long) ago, rich people had chopsticks made (from) jade, gold, or silver. In the (days) of the Chinese dynasty, silver chopsticks (were) used. People believed that silver would (turn) black if it touched poisoned food. (We) know now that silver will not (react) to poison. -

Okonomiyaki by Chef Philli

Okonomiyaki By Chef Philli Serves Prep time Cook time Total time 2-3 20 mins 20 mins 40 mins Chef Skills: Learn how to make Japan’s answer to a pizza Ingredients Equipment ● ½ tsp salt ● Pallet knife ● ½ tsp white sugar ● Baking parchment ● 80g plain flour ● Pizza tray or large tray ● 1 tsp bicarbonate of soda ● Mandoline ● 80ml water ● Whisk or chopsticks ● 2 eggs - lightly whisked ● Piping bag ● 2 handfuls spring onions - thinly ● Large frying pan with lid sliced ● 1 small white cabbage - thinly sliced ● 30g pink pickled ginger Before you click play ● 1 tsp rice wine vinegar ● Get out all equipment & ● 4-6 rashers of streaky bacon measure ingredients ● Handful of furikake (see ● Slice cabbage and spring onions furikake episode) as described ● Mayonnaise ● Make the takoyaki sauce by Ingredients for takoyaki sauce combining all ingredients ● 1 tbsp ketchup ● 1 tbsp oyster sauce ● 1 tsp worcestershire sauce ● 1 tbsp brown sugar 1 of 3 - Next Okonomiyaki By Chef Philli Method 1. To make the batter add the plain flour, sugar, a pinch of salt and baking soda in large mixing bowl. Mix the ingredients with a whisk or a pair of chopsticks. 2. Add the water and the eggs and whisk to incorporate all the ingredients. 3. Add the cabbage, spring onions and the pickled ginger. Mix together, ensuring that the cabbage is fully coated with the batter. 4. Cut two round pieces of baking paper and place one into your frying pan - this is your cartouche - save the other for later. 5. Add rice wine vinegar and place into the mixing bowl with the okonomiyaki batter. -

Silent Auction Items (As of 3/13/17) Art & Home

Silent Auction Items (as of 3/13/17) Art & Home Item # Description Value Donor 100 Red & Black Crocheted Heart Blanket $65 Kathy Peterson 101 102 4 Homemade Soy Jar Candles $30 Rebecca Stearns - RMS Candle Co. 103/104 Asian Placemats w/ Chopsticks- 2 offers $25 Jason Lee & Sharon Wilmans 105 Beautiful Korean Lacquer Ware Tray w/ Mother of $75 Jason Lee Family Pearl Inlay 106 Beautiful Korean Lacquer Ware w/ Mother of Pearl $75 Jason Lee Family Inlay 107 108 Felt Basket w/ Penguin and Bird Ornaments, VT Towel $75 PURE Original & VT Bracelet 109 Pledge of Allegiance Wall Hanging $15 Judy Weisgerber- Hobby Lobby 110 Handmade Blue & Gray 4ft x 5 ft Crocheted Afghan $50 Ethel Fennick (Judy’s mom) 111 Handmade Blue, Brown & Beige 3ft x 7 ft Crocheted $50 Ethel Fennick Afghan 112 Mikasa Glass Candy Dish Adrianne Weisgerber 113 RedKen Products $88 Heidi Senecal- Artistic Styles 114 Framed Oil Painting - Valley View $250 Steve & Ruth Hall 115 “A Friend Loves At All Times” Proverbs 17:17 Mug w/ $12 Judy Weisgerber Attached Tea Bag Holder 116 2 “Live Well, Laugh Often, Love Much” Flower Vases $25 Jennifer Brooks w/ 2 Cherubs 117 Large Canvas Picture - “Bicycle w/ Basket of Flowers” $35 The Burchfield’s 118/119 1 Liter of Maple Syrup - 2 offers $25 Severy Brothers - Severy Family Maple 120 6 Stuart Crystal Hand Cut Goblets $50 The Deibler’s 121 “Joy of a Summer Garden” Table Runner - $125 Susan Hansen One-of-a-kind hand sewn wool primitive table runner collaboratively designed by RACS student Rosie Nop. -

Bacterial Transfer from Mouth to Different Utensils and from Utensils to Food Chaitali Purohit Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2009 Bacterial transfer from mouth to different utensils and from utensils to food Chaitali Purohit Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Food Science Commons Recommended Citation Purohit, Chaitali, "Bacterial transfer from mouth to different utensils and from utensils to food" (2009). All Theses. 623. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/623 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BACTERIAL TRANSFER FROM MOUTH TO UTENSILS AND FROM UTENSIILS TO FOOD A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Masters of Food Science, Nutrition & Culinary Science by Chaitali Purohit August 2009 Accepted by: Dr. Paul L. Dawson, Committee Chair Dr. Julie Northcutt Dr. Xiuping Jiang ABSTRACT This study examined transfer of bacteria from mouth to different surfaces (spoon, chopstick, hand) and from surfaces to food (chicken broth, rice). Three different sets of experiments were conducted. In the first experiment, bacterial transfer from mouth to utensils (spoon or chopstick) was determined. The second experiment measured bacterial transfer from mouth to broth and included scooping and stirring with a spoon. In the third experiment, bacterial transfer from mouth to food rice was tested using either spoon or hand. Ten or seven subjects were used for each of the three experiments. Results indicated that there was a transfer of approximately 5 log10cfu of total bacteria to the spoon or chopstick when either was placed in the mouth with or without food. -

Chopsticks As a Cultural Symbol in China

IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME) e-ISSN: 2320–7388,p-ISSN: 2320–737X Volume 1, Issue 4 (May. –Jun. 2013), PP 01-02 www.iosrjournals.org Chopsticks as a Cultural Symbol in China Chen Desheng & Tang Zheng Ph.D. Scholar,Department of English and Foreign Languages,Bharathiar University,Coimbatore-641046 II M.A English literature, Department of English, R.V.S College of Arts & Science, Coimbatore-641402 Abstract: Food is the soul of health. On such occasions as birthday, food becomes a cultural show in today’s society. When food from one country becomes in another, it leads a kind of cultural exchange. China has a rich tradition of food culture which has spread around the world. As a society develops, food culture too evolves resulting in variety. Each geographical location makes its own food with unique taste and flavor. Sour, sweet, bitter and hot are the tastes of various food items. Apart from being food, they tell us about the people who make it, their culture and nation. The tools which people use to eat are not only tools, but also symbols, tokens of that culture. The practice of using chopsticks has existed from ancient times among the East Asians, especially the Chinese. Made of different materials like gold, silver, copper, wood and bamboo, the chopsticks also express the artistic and aesthetic sensibility of the Chinese people. History tells us that the different colors, sizes and materials of chopsticks have specific meanings. They may stand for position, treasure, luck and so on. This paper attempts to study the importance of chopsticks as a dominant cultural symbol in China. -

Skill-A-Thon Booklet

Foods And Cooking id 1 Apple Corer — This tool has a circular cutting edge that is forced down into the Apple Slicer — This apple, allowing the apple to remain whole so professional-quality tool is it can then be easily sliced into sections for pressed down over the apple to eating it out of hand or baking it whole with make eight uniform slices and the outer skin. A tool used to extract the core remove the core. from the apple without cutting the apple into sections and then individually cutting out each part of the core. Chef’s Knife — A large knife with a wide blade, generally BBQ Tongs — A utensil with considered all-purpose knives long handles used to grip and that are used for cutting and turn food while cooking. dicing. BBQ Spatula — A utensil with long handle and flat bottom used to turn food while cooking. Chopper — A utensil used to cut food into smaller pieces. 2 Chopsticks — A pair of slender sticks made especially of wood or ivory, held between the thumb and fingers and used as an eating utensil in Asian countries and in Cookie Cutter — A shaped template restaurants serving Asian food. with a sharp edge used to cut cookies or biscuits from rolled dough Decorative Slicer, Ripple — A utensil Decorative Slicer, Vee — A utensil used used to cut food that leaves a rippled edge. to cut food that leaves a vee shape Egg Slicer — A kitchen tool with a Egg Separator — A spoon shaped utensil, slatted , egg-shaped hollow on the bottom which has a hole in the bottom and is used and a hinged top consisting of 10 fine steel to separate the white from the yolk of the wires. -

Learn to Use Chopsticks はし

THE JAPANESE HOUSE KYO NO MACHIYA はし ACTIVITIES Learn to Use Chopsticks ACTIVITIES Learn chopsticks culture and etiquette in Japan and try it yourself! TIME: 25 minutes MATERIALS: • Video: Many Homes in Kyoto, Japan—Shiori • A pair of chopsticks • Small items to pick up 1. Learn about Hashi—Chopsticks Chopsticks in Japanese are called hashi; o-hashi is the more polite way to PRONUNCIATION say it. They are made from a variety of materials: wood (including GUIDE: lacquered wood), bamboo, metals, and plastics, but wooden chopsticks Hashi: Hah-she are the most common. There are different kinds of chopsticks for different uses: for eating, for cooking, and for picking up or serving cakes O-hashi: oh hah-she and sweets. Mai-hashi: mah-ee hah- At home, each person has his or her own pair of chopsticks for daily she use. Many people also have a second pair of chopsticks called mai-hashi (my chopsticks) that they would carry with them all the time for use at work or at restaurants. Even though disposable wooden chopsticks are still commonly used at fast food stores and restaurants, people like to have their mai-hashi because it minimizes waste and is better for the environment. Children in Japan usually start learning to use chopsticks by the age of 4 or 5. There are various training chopsticks available for beginner users. 1 © 2013 Boston Children’s Museum KYO NO MACHIYA ACTIVITIES 2. How to Hold a Pair of Hashi Before you start—Watch the chapter “Shiori” in the video: “Many Homes in Kyoto, Japan.” Shiori and her mom prepare hamburger and eat it with rice. -

Pleasure of Manual Kitchen Products: a Checklist for Designing Manual Kitchen Tools By

Pleasure of manual kitchen products: A checklist for designing manual kitchen tools by Ying Su A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Industrial Design Auburn, Alabama May 7, 2016 Keywords: Pleasure design, Ergonomic factors, Four pleasures, Design Checklist Copyright 2016 by Ying Su Approved by Rich Britnell, Chair, Professor of Industrial Design Randy Bartlett, Professor of Industrial Design Shea Tillman, Associate Professor of Industrial Design Abstract As the heart of the home, the kitchen is always a happening place. It can be used to entertain family, cook that holiday meal, or just scrounge for the latest snack. Kitchen tools have an important role in creating entertainment and pleasure in the kitchen. Depending on consumers’ preferences, they can have a chef’s kitchen with professional tools, such as a good set of knives. Or users can enjoy their own modern host’s kitchen, with a bar, counter stools, and plenty of baking tools. As people have increasing expectations for their kitchen products, it will be important to designing pleasurable, high quality manual kitchen tools. In the future, designing pleasurable kitchen tools would allow consumers to use and enjoy the products at the same time. This study will use research to explore the most important elements that a pleasurable kitchen product could have and develop a process for designing pleasurable kitchen products. In order to develop a checklist for designing pleasurable kitchen products, one rule that needs to be understood is that products affect users not only physically but also psychologically. -

American Restaurant Culture and the Rise of the Middle Class, 1880-1920

TURNING THE TABLES: AMERICAN RESTAURANT CULTURE AND THE RISE OF THE MIDDLE CLASS, 1880-1920 by Andrew Peter Haley BA, Tufts University, 1991 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 1997 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Andrew Peter Haley It was defended on May 26, 2005 and approved by Dr. Paula Baker, History, The Ohio State University Co-Dissertation Director Dr. Donna Gabaccia, History, University of Pittsburgh Co-Dissertation Director Dr. Richard Oestreicher, History, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Carol Stabile, Communications, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Bruce Venarde, History, University of Pittsburgh ii © Andrew Peter Haley iii TURNING THE TABLES: AMERICAN RESTAURANT CULTURE AND THE RISE OF THE MIDDLE CLASS, 1880-1920 Andrew Peter Haley, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation examines changes in restaurant dining during the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era as a means of understanding the growing influence of the middle- class consumer. It is about class, consumption and culture; it is also about food and identity. In the mid-nineteenth century, restaurants served French food prepared by European chefs to elite Americans with aristocratic pretensions. “Turning the Tables” explores the subsequent transformation of aristocratic restaurants into public spaces where the middle classes could feel comfortable dining. Digging deeply into the changes restaurants underwent at the turn of the century, I argue that the struggles over restaurant culture—the battles over the French-language menu, the scientific eating movement, the celebration of cosmopolitan cuisines, the growing acceptance of unescorted women diners, the failed attempts to eliminate tipping—offer evidence that the urban middle class would play a central role in the construction of twentieth-century American culture.