Supporting Roles in Food Culture Chopsticks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’S Daughters – Part 2

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 8. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Abstract This section discusses the complex psychological and philosophical reason for Shogun Yoshimune’s contrasting handlings of his two adopted daughters’ and his favorite son’s weddings. In my thinking, Yoshimune lived up to his philosophical principles by the illogical, puzzling treatment of the three weddings. We can witness the manifestation of his modest and frugal personality inherited from his ancestor Ieyasu, cohabiting with his strong but unconventional sense of obligation and respect for his benefactor Tsunayoshi. Disciplines Family, Life Course, and Society | Inequality and Stratification | Social and Cultural Anthropology This is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 Weddings of Shogun’s Daughters #2- Seigle 1 11Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 e. -

Chopsticks Is a Divine Art of Chinese Culture

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 2, Issue - 11, Nov – 2018 Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Impact Factor: 4.526 Publication Date: 30/11/2018 Chopsticks is a Divine Art of Chinese Culture Md. Abu Naim Shorkar School of Economics, Shanghai University, 99, Shangda Road, Shanghai, China, 200444, Email – [email protected] Abstract: Chopsticks are the primary eating instrument in Chinese culture, and every youngster has to adopt using technique and controlling of chopsticks. A couple of chopsticks is the main instrument for eating, and the physical movements of control are familiar with Chinese. The Chinese use chopsticks as natural as Caucasians use knives and forks. An analogy of chopsticks is as an extension of one’s fingers. Chinese food is prepared so that it may be easily handled with chopsticks. In fact, many traditional Chinese families do not have forks at home. The usage of chopsticks has been deeply mixed into Chinese culture. In any occasions, food has become a cultural show in today’s society. When food from single nation becomes in another, it leads to a sort of cultural interchange. China delivers a deep tradition of food culture which has spread around the globe. As a company rises, food culture too evolves resulting in mutations. Each geographical location makes its own food with unparalleled taste and smell. Sullen, sweet, bitter and hot are the preferences of several food items. Apart from being good, they tell us about the people who make it, their culture and nation. The creatures which people apply to eat are not only creatures, but also symbols, relics of that civilization. -

Korean Food and American Food by Yangsook

Ahn 1 Yangsook Ahn Instructor’s Name ENGL 1013 Date Korean Food and American Food Food is a part of every country’s culture. For example, people in both Korea and America cook and serve traditional foods on their national holidays. Koreans eat ddukguk, rice cake soup, on New Year’s Day to celebrate the beginning of a new year. Americans eat turkey on Thanksgiving Day. Although observing national holidays is a similarity between their food cultures, Korean food culture differs from American food culture in terms of utensils and appliances, ingredients and cooking methods, and serving and dining manners. The first difference is in utensils and appliances. Koreans’ eating utensils are a spoon and chopsticks. Koreans mainly use chopsticks and ladles to cook side dishes and soups; also, scissors are used to cut meats and other vegetables, like kimchi. Korean food is based on rice; therefore, a rice cooker is an important appliance. Another important appliance in Korean food culture is a kimchi refrigerator. Koreans eat many fermented foods, like kimchi, soybean paste, and red chili paste. For this reason, almost every Korean household has a kimchi refrigerator, which is designed specifically to meet the storage requirements of kimchi and facilitate different fermentation processes. While Koreans use a spoon and chopsticks, Americans use a fork and a knife as main eating utensils. Americans use various cooking utensils like a spatula, tongs, spoon, whisk, peeler, and measuring cups. In addition, the main appliance for American food is an oven since American food is based on bread. A fryer, toaster, and blender are also important equipment to Ahn 2 prepare American foods. -

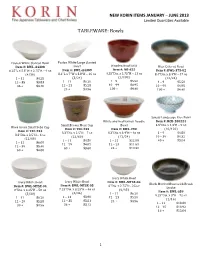

2013.01-06 New Korin Items

NEW$KORIN$ITEMS$JANUARY$–$JUNE$2013$ Limited'Quantities'Available' ' TABLEWARE:"Bowls" " " " Fusion"White"Slanted"Bowl" Fusion"White"Large"Slanted" " " Item%#:%BWL+A4308% Bowl" Wooden"Bowl"RED" Blue"Colored"Bowl" 6.25"L"x"5.5"W"x"2.75"H"–"9"oz" Item%#:%BWL+A4309% Item%#:%NR+625% Item%#:%BWL+375+02% (4/36)" 8.1”L"x"7”W"x"3.8"H"–"16"oz" 4.25"Dia."x"2.75"H"–"11"oz" 8.4"Dia."x"3.4"H"–"47"oz" 1"–"11" $4.25" (3/24)" (1/100)" (12/24)" 12"–"35" $3.83" 1"–"11" $6.20" 1"–"9" $5.50" 1"–"9" $5.50" 36"+" $3.40" 12"–"23" $5.58" 10"–"99" $4.95" 10"–"99" $4.95" " " 24"+" $4.96" 100"+" $4.40" 100"+" $4.40" " " " " " " " " " " " " Sansui"Landscape"Rice"Bowl" " White"and"Red"Ramen"Noodle" Item%#:%RCB+200224% " Small"Brown"Moss"Cup" Bowl" 4.5"Dia."x"1.3"H"–"9"oz" Hiwa"Green"Small"Soba"Cup" Item%#:%TEC+233% Item%#:%BWL+290% (10/120)" Item%#:%TEC+234% 3.3”Dia."x"2.5"H"–"7"oz" 8.3”Dia."x"3.4"H"–"46"oz" 1"–"9" $4.80" 3.3”Dia."x"2.5"H"–"6"oz" (12/60)" (12/24)" 10"–"39" $4.32" (12/60)" 1"–"11" $4.50" 1"–"11" $12.90" 40"+" $3.84" 1"–"11" $6.00" " " 12"–"59" $4.05" 12"–"23" $11.61" " 12"–"59" $5.40" 60"+" $3.60" 24"+" $10.32" 60"+" $4.80" " " " " " " Ivory"White"Bowl" Ivory"White"Bowl" Item%#:%BWL+MTSX+06% " Ivory"White"Bowl" Black"Mottled"Bowl"with"Brush" Item%#:%BWL+MTSX+05% 6"Dia."x"2.75"H"\"25"oz" Item%#:%BWL+MTSX+04% Stroke" 7.25"Dia."x"3.25"H"–"46"oz" (6/48)" 8"Dia."x"3.25"H"–"58"oz" Item%#:%BWL+S59% (6/36)" 1"–"11" $6.20" (5/30)" 9.25"Dia."x"3"H"–"72"oz" 1"–"11" $3.90" 12"–"23" $5.58" 1"–"11" $6.20" (1/16)" 12"–"35" $3.51" 24"+" $4.96" 12"–"29" $5.58" 1"–"11" -

Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto

, East Asian History NUMBERS 17/18· JUNE/DECEMBER 1999 Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University 1 Editor Geremie R. Barme Assistant Editor Helen Lo Editorial Board Mark Elvin (Convenor) John Clark Andrew Fraser Helen Hardacre Colin Jeffcott W. ]. F. Jenner Lo Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Design and Production Helen Lo Business Manager Marion Weeks Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This double issue of East Asian History, 17/18, was printed in FebrualY 2000. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 26249 3140 Fax +61 26249 5525 email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Subscriptions, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Whose Strange Stories? P'u Sung-ling (1640-1715), Herbert Giles (1845- 1935), and the Liao-chai chih-yi John Minford and To ng Man 49 Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto 71 Was Toregene Qatun Ogodei's "Sixth Empress"? 1. de Rachewiltz 77 Photography and Portraiture in Nineteenth-Century China Regine Thiriez 103 Sapajou Richard Rigby 131 Overcoming Risk: a Chinese Mining Company during the Nanjing Decade Ti m Wright 169 Garden and Museum: Shadows of Memory at Peking University Vera Schwarcz iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing M.c�J�n, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Talisman-"Passport for wandering souls on the way to Hades," from Henri Dore, Researches into Chinese superstitions (Shanghai: T'usewei Printing Press, 1914-38) NIHONBASHI: EDO'S CONTESTED CENTER � Marcia Yonemoto As the Tokugawa 11&)II regime consolidated its military and political conquest Izushi [Pictorial sources from the Edo period] of Japan around the turn of the seventeenth century, it began the enormous (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1975), vol.4; project of remaking Edo rI p as its capital city. -

Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主

East Asian Science, Technology and Society: an International Journal DOI 10.1007/s12280-008-9042-9 Sinophiles and Sinophobes in Tokugawa Japan: Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主 Benjamin A. Elman Received: 12 May 2008 /Accepted: 12 May 2008 # National Science Council, Taiwan 2008 Abstract This article first reviews the political, economic, and cultural context within which Japanese during the Tokugawa era (1600–1866) mastered Kanbun 漢 文 as their elite lingua franca. Sino-Japanese cultural exchanges were based on prestigious classical Chinese texts imported from Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) China via the controlled Ningbo-Nagasaki trade and Kanbun texts sent in the other direction, from Japan back to China. The role of Japanese Kanbun teachers in presenting language textbooks for instruction and the larger Japanese adaptation of Chinese studies in the eighteenth century is then contextualized within a new, socio-cultural framework to understand the local, regional, and urban role of the Confucian teacher–scholar in a rapidly changing Tokugawa society. The concluding part of the article is based on new research using rare Kanbun medical materials in the Fujikawa Bunko 富士川文庫 at Kyoto University, which show how some increasingly iconoclastic Japanese scholar–physicians (known as the Goiha 古醫派) appropriated the late Ming and early Qing revival of interest in ancient This article is dedicated to Nathan Sivin for his contributions to the History of Science and Medicine in China. Unfortunately, I was unable to present it at the Johns Hopkins University sessions in July 2008 honoring Professor Sivin or include it in the forthcoming Asia Major festschrift in his honor. -

Chopsticks and the Land of the Five Flavors

History in the Making Volume 9 Article 14 January 2016 Comparative Book Review: Chopsticks and The Land of the Five Flavors Jacob P, Banda CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Banda, Jacob P, (2016) "Comparative Book Review: Chopsticks and The Land of the Five Flavors," History in the Making: Vol. 9 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol9/iss1/14 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reviews Comparative Book Review: Chopsticks and The Land of the Five Flavors By Jacob P. Banda Food and foodways provide a valuable window into Chinese history and culture. Scholars have, until recently, not sufficiently explored them as great potential frameworks for analyzing Chinese history. They are rich potential sources of insights on a wide range of important themes that are crucial to the understanding of Chinese society, both past and present. Historians have tended to favor written sources and particularly those of social and political elites, often at the expense of studying important cultural practices and the history of daily life. The creative use of unconventional sources can reward the scholar with a richer view of daily life, with food and foodways as one of the most important dimensions. -

Zen Painting & Calligraphy

SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC LIBRARY 1223 02649 4907 amiEDUE [ SEPT 2 1997, 1I- —g—' 1» "> f ^ ' Bk Printed in USA . /30 CT - 8 1991 'painting £*- Calligraphy An exhibition of works of art lent by temples, private collectors, and public and private museums in Japan, organized in collaboration with the Agency for Cultural Affairs of the Japanese Government. Jan Fontein & Money L. Hickman of fine Arti, Boston Distributed by New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, Connecticut Copyright © 1970 by Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts All rights reserved ISBN 0-87846-001-2 Library of Congress Catalogue Card No. 76-127853 Typeset in Linofilm Palatino by Wrightson Typographers, Boston Printed by The Meriden Gravure Co., Meriden, Conn. Designed by Carl F. Zahn Dates of the Exhibition: November 5-December 20,1970 709-5,F737z Fontein, Jan Zen painting et v calligraphy Cover illustration: 20. "Red-Robed" Bodhidharma, artist, unknown, ca. 1271 Title page illustration: 48. Kanzan and Jittoku, traditionally attributed to Shubun (active second quarter of 15th century) (detail) S.F. PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1223 02649 4907 I Contents Foreword vii Preface ix Acknowledgments xi Chronology xii Introduction xiii The Beginnings of Ch'an Buddhism, xiii Chinese and Indian Thought in Ch'an Buddhism, xiv The Northern and Southern Schools, xvi The Earliest Form of Ch'an Art, xvi The Consolidation and Expansion of the Ch'an Sect, xvii Kuan-hsiu (832-912): The Birth of Ch'an Art, xix Ch'an Literature and Koan, xxi Ch'an Art during the Northern Sung Period (960-1126), XXII Ch'an -

The Old Tea Seller

For My Wife Yoshie Portrait of Baisaō. Ike Taiga. Inscription by Baisaō. Reproduced from Eastern Buddhist, No. XVII, 2. The man known as Baisaō, old tea seller, dwells by the side of the Narabigaoka Hills. He is over eighty years of age, with a white head of hair and a beard so long it seems to reach to his knees. He puts his brazier, his stove, and other tea implements in large bamboo wicker baskets and ports them around on a shoulder pole. He makes his way among the woods and hills, choosing spots rich in natural beauty. There, where the pebbled streams run pure and clear, he simmers his tea and offers it to the people who come to enjoy these scenic places. Social rank, whether high or low, means nothing to him. He doesn’t care if people pay for his tea or not. His name now is known throughout the land. No one has ever seen an expression of displeasure cross his face, for whatever reason. He is regarded by one and all as a truly great and wonderful man. —Fallen Chestnut Tales Contents PART 1: The Life of Baisaō, the Old Tea Seller PART 2: Translations Notes to Part 1 Selected Bibliography Glossary/Index Introductory Note THE BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH of Baisaō in the first section of this book has been pieced together from a wide variety of fragmented source material, some of it still unpublished. It should be the fullest account of his life and times yet to appear. As the book is intended mainly for the general reader, I have consigned a great deal of detailed factual information to the notes, which can be read with the text, afterwards, or disregarded entirely. -

Chopsticks: a Chinese Invention 507 Sopris West Six Minute Solutions Passage

Curriculum-Based Measurement: Maze Passage: Examiner Copy Student/Classroom: _____________________ Examiner: ____________ Assessment Date: _______ Chopsticks: A Chinese Invention 507 Sopris West Six Minute Solutions Passage Chopsticks were invented in China more than 5,000 years ago. Long ago, food was chopped into (little) pieces so it would cook faster. (The) faster food cooked, the more fuel (it) would save. Since food was eaten (in) small pieces, there was no need (for) knives. Rather, chopsticks were used to (move) food from the plate to the (mouth). Confucius was a Chinese philosopher. He (was) a vegetarian. It is believed that (Confucius) did not like knives. Knives reminded (him) of the slaughterhouse. He favored chopsticks. (By) A.D.500, the use of chopsticks (had) spread to other countries. The people (in) present day Vietnam, Korea, and Japan, (as) well as China, use chopsticks today. (Chinese) chopsticks are about 9 or 10 inches long. (They) are square at the top, have (a) blunt end, and are thinner on (the) bottom. The Chinese call them kuai-ai. (This) means "quick little fellows." Chopsticks have (been) made of many materials. Bamboo is (a) popular choice since it is available, (and) inexpensive. Bamboo is also heat resistant. (Other) types of wood such as sandalwood, (cedar), and teak have also been used. (Long) ago, rich people had chopsticks made (from) jade, gold, or silver. In the (days) of the Chinese dynasty, silver chopsticks (were) used. People believed that silver would (turn) black if it touched poisoned food. (We) know now that silver will not (react) to poison. -

Limited IOC-IHO/GEBCO SCUFN-XIV/3 English Only

Distribution : limited IOC-IHO/GEBCO SCUFN-XIV/3 English only INTERGOVERNMENTAL INTERNATIONAL OCEANOGRAPHIC HYDROGRAPHIC COMMISSION (of UNESCO) ORGANIZATION Japan Oceanographic Data Center Tokyo, Japan 17-20 April 2001 SUMMARY REPORT IOC-IHO/GEBCO SCUFN-XIV/3 Page intentionally left blank IOC-IHO/GEBCO SCUFN-XIV/3 Page i ALPHABETIC INDEX OF UNDERSEA FEATURE NAMES CONSIDERED AT SCUFN XIV AND APPEARING IN THIS REPORT (*=new name approved) Name Page Name Page ABY Canyon * 19 ARS Canyon * 94 AÇOR Bank * 26 ATHOS Canyon * 93 AÇOR Fracture Zone 26 'ATI'APITI Seamount 98 AÇORES ESTE Fracture Zone * 26 AUDIERNE Canyon * 90 AÇORES NORTE Fracture Zone 26 AUDIERNE Levee * 90 AÇORES-BISCAY Cordillera 26 AVON Canyon * 78 AEGIR Ridge 23 BAOULÉ Canyon * 19 AEGIS Spur * 87 BEAUGÉ Promontory * 85 AGOSTINHO Seamount * 26 BEIJU Bank * 58 AIGUILLON Canyon * 94 BEIRAL DE VIANA Escarpment * 6 AIX Canyon * 94 BELLE-ILE Canyon * 92 AKADEMIK KURCHATOV 12 BERTHOIS Spur * 86 Fracture Zone * AKE-NO-MYOJO Seamount * 52 BIJAGÓS Canyon * 11 ALBERT DE MONACO Ridge * 27 BIR-HAKEIM Bank 96 ALVARO MARTINS Hill * 27 BLACK Hole * 71 AMAMI Rise 62 BLACK MUD Canyon * 86 AMANOGAWA Seamounts * 69 BLACK MUD Levee * 89 AN-EI Seamount * 74 BLACK MUD SUPERIEUR 95 Seachannel ANITA CONTI Seamounts * 18 BLACK MUD INFERIEUR 95 Seachannel ANNAN Seamount 10 BOGDANOV Fracture Zone * 81 ANTON LEONOV Seamount * 11 BORDA Seamount * 27 ANTONIO DE FREITAS Hill * 27 BOREAS Abyssal Plain 23 ARAKI Seamount * 65 BOURCART Spur 97 ARAMIS Canyon * 93 BOURÉE Hole * 27 ARCACHON Canyon * 92 BRENOT Spur -

Okonomiyaki by Chef Philli

Okonomiyaki By Chef Philli Serves Prep time Cook time Total time 2-3 20 mins 20 mins 40 mins Chef Skills: Learn how to make Japan’s answer to a pizza Ingredients Equipment ● ½ tsp salt ● Pallet knife ● ½ tsp white sugar ● Baking parchment ● 80g plain flour ● Pizza tray or large tray ● 1 tsp bicarbonate of soda ● Mandoline ● 80ml water ● Whisk or chopsticks ● 2 eggs - lightly whisked ● Piping bag ● 2 handfuls spring onions - thinly ● Large frying pan with lid sliced ● 1 small white cabbage - thinly sliced ● 30g pink pickled ginger Before you click play ● 1 tsp rice wine vinegar ● Get out all equipment & ● 4-6 rashers of streaky bacon measure ingredients ● Handful of furikake (see ● Slice cabbage and spring onions furikake episode) as described ● Mayonnaise ● Make the takoyaki sauce by Ingredients for takoyaki sauce combining all ingredients ● 1 tbsp ketchup ● 1 tbsp oyster sauce ● 1 tsp worcestershire sauce ● 1 tbsp brown sugar 1 of 3 - Next Okonomiyaki By Chef Philli Method 1. To make the batter add the plain flour, sugar, a pinch of salt and baking soda in large mixing bowl. Mix the ingredients with a whisk or a pair of chopsticks. 2. Add the water and the eggs and whisk to incorporate all the ingredients. 3. Add the cabbage, spring onions and the pickled ginger. Mix together, ensuring that the cabbage is fully coated with the batter. 4. Cut two round pieces of baking paper and place one into your frying pan - this is your cartouche - save the other for later. 5. Add rice wine vinegar and place into the mixing bowl with the okonomiyaki batter.