The Interpretation of the New Heavens and Earth in Seventeenth-Century England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Micah Obadiah Joel and Jonah the Books of the Prophets Micah Obadiah Joel and Jonah

WESTMINSTER COMMENTARIES EDITED BY WALTER LooK D.D. L"-I)y MARGARET PROFESSOR OF DIVINITY Iii THE U!iIVERSITY 011' OXFORD THE BOOKS OF THE PROPHETS MICAH OBADIAH JOEL AND JONAH THE BOOKS OF THE PROPHETS MICAH OBADIAH JOEL AND JONAH WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY G. W. WADE D.D. 8ENIOB TUTOR OF ST DAVID'S COLLEGE, LAXPETBJI, CANON OF BT ASil>H METHUEN & CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET W.C. LONDON First published in 1925 l'BINT.11D IN GREAT BRITAIN DULCISSIMAE DILECTISSIMAE PREFATORY NOTE BY THE GENER.AL EDITOR HE primary object of these Commentaries is to be exe T getical, to interpret the meaning of each book of the Bible in the light of modern knowledge to English readers. The Editors: will not deal, except subordinately, with questions of textual criticism or philology ; but taking the English text in the Revised Version as their basis, they will aim at com bining a hearty acceptance of critical principles with loyalty to the Catholic Faith. The series will be less elementary than the Cambridge Bible for Schools, less critical than the International Critical Com mentary, less didactic than the Expositor's Bible ; and it is hoped that it may be of use both to theological students and to the clergy, as well as to the growing number of educated laymen and laywomen who wish to read the Bible intelligently and reverently. Each commentary will therefore have (i) An Introduction stating the bearing of modern criticism and research upon the historical character of the book, and drawing out the contribution which the book, as a whole, makes to the body of religious truth. -

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

Yahoel As Sar Torah 105 Emblematic Representations of the Divine Mysteries

Orlov: Aural Apocalypticism / 4. Korrektur / Mohr Siebeck 08.06.2017 / Seite III Andrei A. Orlov Yahoel and Metatron Aural Apocalypticism and the Origins of Early Jewish Mysticism Mohr Siebeck Orlov: Aural Apocalypticism / 4. Korrektur / Mohr Siebeck 08.06.2017 / Seite 105 Yahoel as Sar Torah 105 emblematic representations of the divine mysteries. If it is indeed so, Yahoel’s role in controlling these entities puts him in a very special position as the dis- tinguished experts in secrets, who not only reveals the knowledge of esoteric realities but literally controls them by taming the Hayyot and the Leviathans through his power as the personification of the divine Name. Yahoel as Sar Torah In Jewish tradition, the Torah has often been viewed as the ultimate com- pendium of esoteric data, knowledge which is deeply concealed from the eyes of the uninitiated. In light of this, we should now draw our attention to another office of Yahoel which is closely related to his role as the revealer of ultimate secrets – his possible role as the Prince of the Torah or Sar Torah. The process of clarifying this obscure mission of Yahoel has special sig- nificance for the main task of this book, which attempts to demonstrate the formative influences of the aural ideology found in the Apocalypse of Abraham on the theophanic molds of certain early Jewish mystical accounts. In the past, scholars who wanted to demonstrate the conceptual gap between apocalyptic and early Jewish mystical accounts have often used Sar Torah sym- bolism to illustrate such discontinuity between the two religious phenomena. -

MARS DURING the PRE-NOACHIAN. J. C. Andrews-Hanna1 and W. B. Bottke2, 1Lunar and Planetary La- Boratory, University of Arizona

Fourth Conference on Early Mars 2017 (LPI Contrib. No. 2014) 3078.pdf MARS DURING THE PRE-NOACHIAN. J. C. Andrews-Hanna1 and W. B. Bottke2, 1Lunar and Planetary La- boratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, [email protected], 2Southwest Research Institute and NASA’s SSERVI-ISET team, 1050 Walnut St., Suite 300, Boulder, CO 80302. Introduction: The surface geology of Mars appar- ing the pre-Noachian was ~10% of that during the ently dates back to the beginning of the Early Noachi- LHB. Consideration of the sawtooth-shaped exponen- an, at ~4.1 Ga, leaving ~400 Myr of Mars’ earliest tially declining impact fluxes both in the aftermath of evolution effectively unconstrained [1]. However, an planet formation and during the Late Heavy Bom- enduring record of the earlier pre-Noachian conditions bardment [5] suggests that the impact flux during persists in geophysical and mineralogical data. We use much of the pre-Noachian was even lower than indi- geophysical evidence, primarily in the form of the cated above. This bombardment history is consistent preservation of the crustal dichotomy boundary, to- with a late heavy bombardment (LHB) of the inner gether with mineralogical evidence in order to infer the Solar System [6] during which HUIA formed, which prevailing surface conditions during the pre-Noachian. followed the planet formation era impacts during The emerging picture is a pre-Noachian Mars that was which the dichotomy formed. less dynamic than Noachian Mars in terms of impacts, Pre-Noachian Tectonism and Volcanism: The geodynamics, and hydrology. crust within each of the southern highlands and north- Pre-Noachian Impacts: We define the pre- ern lowlands is remarkably uniform in thickness, aside Noachian as the time period bounded by two impacts – from regions in which it has been thickened by volcan- the dichotomy-forming impact and the Hellas-forming ism (e.g., Tharsis, Elysium) or thinned by impacts impact. -

Islamic Calendar from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Islamic calendar From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia -at اﻟﺘﻘﻮﻳﻢ اﻟﻬﺠﺮي :The Islamic, Muslim, or Hijri calendar (Arabic taqwīm al-hijrī) is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 months in a year of 354 or 355 days. It is used (often alongside the Gregorian calendar) to date events in many Muslim countries. It is also used by Muslims to determine the proper days of Islamic holidays and rituals, such as the annual period of fasting and the proper time for the pilgrimage to Mecca. The Islamic calendar employs the Hijri era whose epoch was Islamic Calendar stamp issued at King retrospectively established as the Islamic New Year of AD 622. During Khaled airport (10 Rajab 1428 / 24 July that year, Muhammad and his followers migrated from Mecca to 2007) Yathrib (now Medina) and established the first Muslim community (ummah), an event commemorated as the Hijra. In the West, dates in this era are usually denoted AH (Latin: Anno Hegirae, "in the year of the Hijra") in parallel with the Christian (AD) and Jewish eras (AM). In Muslim countries, it is also sometimes denoted as H[1] from its Arabic form ( [In English, years prior to the Hijra are reckoned as BH ("Before the Hijra").[2 .(ﻫـ abbreviated , َﺳﻨﺔ ﻫِ ْﺠﺮﻳّﺔ The current Islamic year is 1438 AH. In the Gregorian calendar, 1438 AH runs from approximately 3 October 2016 to 21 September 2017.[3] Contents 1 Months 1.1 Length of months 2 Days of the week 3 History 3.1 Pre-Islamic calendar 3.2 Prohibiting Nasī’ 4 Year numbering 5 Astronomical considerations 6 Theological considerations 7 Astronomical -

Wittgenstein's Critical Physiognomy

Nordic Wittgenstein Review 3 (No. 1) 2014 Daniel Wack [email protected] Wittgenstein’s Critical Physiognomy Abstract In saying that meaning is a physiognomy, Wittgenstein invokes a philosophical tradition of critical physiognomy, one that developed in opposition to a scientific physiognomy. The form of a critical physiognomic judgment is one of reasoning that is circular and dynamic, grasping intention, thoughts, and emotions in seeing the expressive movements of bodies in action. In identifying our capacities for meaning with our capacities for physiognomic perception, Wittgenstein develops an understanding of perception and meaning as oriented and structured by our shared practical concerns and needs. For Wittgenstein, critical physiognomy is both fundamental for any meaningful interaction with others and a capacity we cultivate, and so expressive of taste in actions and ways of living. In recognizing how fundamental our capacity for physiognomic perception is to our form of life Wittgenstein inherits and radicalizes a tradition of critical physiognomy that stretches back to Kant and Lessing. Aesthetic experiences such as painting, poetry, and movies can be vital to the cultivation of taste in actions and in ways of living. Introduction “Meaning is a physiognomy.” –Ludwig Wittgenstein (PI, §568) In claiming that meaning is a physiognomy, Wittgenstein appears to call on a discredited pseudo-science with a dubious history of justifying racial prejudice and social discrimination in order to 113 Daniel Wack BY-NC-SA elucidate his understanding of meaning. Physiognomy as a science in the eighteenth and nineteenth century aimed to provide a model of meaning in which outer signs serve as evidence for judgments about inner mental states. -

Heaven in the Early History of Western Religions

Alison Joanne GREIG University of Wales Trinity Saint David MA in Cultural Astronomy and Astrology Module Name: Dissertation Module Code: AHAH7001 Alison Joanne Greig Student No. 27001842 31 December 2012 Heaven in the early history of Western religions Chapter 1 Approaches to concepts of heaven This dissertation examines concepts of heaven in the early history of Western religions and the extent to which themes found in other traditions are found in Christianity. Russell, in A History of Heaven, investigates the origins of the concept of heaven, which he dates at about 200 B.C.E. and observes that heaven, a concept that has shaped much of Christian thought and attitudes, has been strangely neglected by modern historians.1 Christianity has played a central role in Western civilization and instructs its believers to direct their life in this world with a view to achieving eternal life in the next, as observed by Liebeschuetz. 2 It is of the greatest historical importance that a very large number of people could for many centuries be persuaded to see life in an imperfect visible world as merely a stage in their progress to a world that was perfect but invisible; yet, it has been neglected as a subject for study. Russell notes that Heaven: A History3 by McDannell and Lang mainly offers sociological insights.4 Russell holds that the most important aspects of the concept of heaven are the beatific vision and the mystical union.5 Heaven, he says, is the state of being in 1 Jeffrey Burton Russell, A History of Heaven – The Singing Silence (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997) xiii, xiv. -

Treasury's Emergency Rental Assistance

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: TREASURY’SHEADING EMERGENCY1 HERE RENTAL ASSISTANCEHEADING (ERA)1 HERE PROGRAM AUGUST 2021 ongress established an Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) program administered by the U.S. Department of the Treasury to distribute critically needed emergency rent and utility assistance to Cmillions of households at risk of losing their homes. Congress provided more than $46 billion for emergency rental assistance through the Consolidated Appropriations Act enacted in December 2020 and the American Rescue Plan Act enacted in March 2021. Based on NLIHC’s ongoing tracking and analysis of state and local ERA programs, including nearly 500 programs funded through Treasury’s ERA program, NLIHC has continued to identify needed policy changes to ensure ERA is distributed efficiently, effectively, and equitably. The ability of states and localities to distribute ERA was hindered early on by harmful guidance released by the Trump administration on its last day in office. Immediately after President Biden was sworn into office, the administration rescinded the harmful FAQ and released improved guidance to ensure ERA reaches households with the greatest needs, as recommended by NLIHC. The Biden administration issued revised ERA guidance in February, March, May, June, and August that directly addressed many of NLIHC’s concerns about troubling roadblocks in ERA programs. Treasury’s latest guidance provides further clarity and recommendations to encourage state and local governments to expedite assistance. Most notably, the FAQ provides even more explicit permission for ERA grantees to rely on self-attestations without further documentation. WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO RECEIVE EMERGENCY RENTAL ASSISTANCE? Households are eligible for ERA funds if one or more individuals: 1. -

Geologic History of the Earth 1 the Precambrian

Geologic History of the Earth 1 algae = very simple plants that Geologists are scientists who study the structure grow in or near the water of rocks and the history of the Earth. By looking at first = in the beginning at and examining layers of rocks and the fossils basic = main, important they contain they are able to tell us what the beginning = start Earth looked like at a certain time in history and billion = a thousand million what kind of plants and animals lived at that breathe = to take air into your lungs and push it out again time. carbon dioxide = gas that is produced when you breathe Scientists think that the Earth was probably formed at the same time as the rest out of our solar system, about 4.6 billion years ago. The solar system may have be- certain = special gun as a cloud of dust, from which the sun and the planets evolved. Small par- complex = something that has ticles crashed into each other to create bigger objects, which then turned into many different parts smaller or larger planets. Our Earth is made up of three basic layers. The cen- consist of = to be made up of tre has a core made of iron and nickel. Around it is a thick layer of rock called contain = have in them the mantle and around that is a thin layer of rock called the crust. core = the hard centre of an object Over 4 billion years ago the Earth was totally different from the planet we live create = make on today. -

Critical Analysis of Article "21 Reasons to Believe the Earth Is Young" by Jeff Miller

1 Critical analysis of article "21 Reasons to Believe the Earth is Young" by Jeff Miller Lorence G. Collins [email protected] Ken Woglemuth [email protected] January 7, 2019 Introduction The article by Dr. Jeff Miller can be accessed at the following link: http://apologeticspress.org/APContent.aspx?category=9&article=5641 and is an article published by Apologetic Press, v. 39, n.1, 2018. The problems start with the Article In Brief in the boxed paragraph, and with the very first sentence. The Bible does not give an age of the Earth of 6,000 to 10,000 years, or even imply − this is added to Scripture by Dr. Miller and other young-Earth creationists. R. C. Sproul was one of evangelicalism's outstanding theologians, and he stated point blank at the Legionier Conference panel discussion that he does not know how old the Earth is, and the Bible does not inform us. When there has been some apparent conflict, either the theologians or the scientists are wrong, because God is the Author of the Bible and His handiwork is in general revelation. In the days of Copernicus and Galileo, the theologians were wrong. Today we do not know of anyone who believes that the Earth is the center of the universe. 2 The last sentence of this "Article In Brief" is boldly false. There is almost no credible evidence from paleontology, geology, astrophysics, or geophysics that refutes deep time. Dr. Miller states: "The age of the Earth, according to naturalists and old- Earth advocates, is 4.5 billion years. -

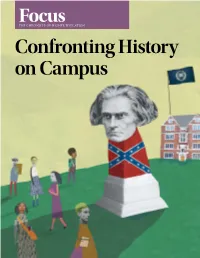

Confronting History on Campus

CHRONICLEFocusFocus THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION Confronting History on Campus As a Chronicle of Higher Education individual subscriber, you receive premium, unrestricted access to the entire Chronicle Focus collection. Curated by our newsroom, these booklets compile the most popular and relevant higher-education news to provide you with in-depth looks at topics affecting campuses today. The Chronicle Focus collection explores student alcohol abuse, racial tension on campuses, and other emerging trends that have a significant impact on higher education. ©2016 by The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, forwarded (even for internal use), hosted online, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For bulk orders or special requests, contact The Chronicle at [email protected] ©2016 THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS OODROW WILSON at Princeton, John Calhoun at Yale, Jefferson Davis at the University of Texas at Austin: Students, campus officials, and historians are all asking the question, What’sW in a name? And what is a university’s responsibil- ity when the name on a statue, building, or program on campus is a painful reminder of harm to a specific racial group? Universities have been grappling anew with those questions, and trying different approaches to resolve them. Colleges Struggle Over Context for Confederate Symbols 4 The University of Mississippi adds a plaque to a soldier’s statue to explain its place there. -

Hannah Halter REL 227: History and Theology of the Early Church Final Essay

1 Hannah Halter REL 227: History and Theology of the Early Church Final Essay Heaven: Defining the Undefinable I was born into a spirited Christian family, so I was made aware of a place called heaven at an early age. I was told it was God’s home, a paradise our loved ones went to after their lives ended. I grew up with heaven in the back of my mind, but recently I have been contemplating what heaven is on a more specific level, instead of accepting the broad, cheerful definitions I inherited. Becoming an adult has brought a high degree of spiritual growth into the forefront of my life. Among all this growing up, my own wonderings about heaven kept resurfacing. I, and perhaps every other human being, am naturally drawn to thoughts that capture my senses, and my musings about heaven are no different. What does it look like? How does it feel to be there? Questions like these almost sound juvenile now that I consider them, but, if given the chance, I trust that any believer would be ecstatic to experience the realm of God during their lives. I began searching for others’ thoughts, and I came across an overwhelming number of people who claim to have taken trips to heaven by the power of Jesus and His angels. They recounted beautiful sensory details, like dazzling colors beyond those of the physical world, adorning a fantastic divine realm they saw with spiritual eyes. I spent hours listening to these stunning testimonies, not even considering if they were the truth or simply hopeful imaginings.