History of Wine-Growing in Lantignié

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

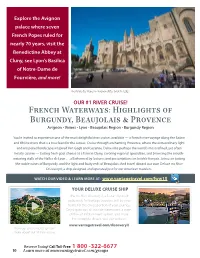

French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence

Explore the Avignon palace where seven French Popes ruled for nearly 70 years, visit the Benedictine Abbey at Cluny, see Lyon’s Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière, and more! The Palais des Popes in Avignon dates back to 1252. OUR #1 RIVER CRUISE! French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence Avignon • Viviers • Lyon • Beaujolais Region • Burgundy Region You’re invited to experience one of the most delightful river cruises available — a French river voyage along the Saône and Rhône rivers that is a true feast for the senses. Cruise through enchanting Provence, where the extraordinary light and unspoiled landscapes inspired Van Gogh and Cezanne. Delve into perhaps the world’s most refined, yet often hearty cuisine — tasting fresh goat cheese at a farm in Cluny, savoring regional specialties, and browsing the mouth- watering stalls of the Halles de Lyon . all informed by lectures and presentations on la table français. Join us in tasting the noble wines of Burgundy, and the light and fruity reds of Beaujolais. And travel aboard our own Deluxe ms River Discovery II, a ship designed and operated just for our American travelers. WATCH OUR VIDEO & LEARN MORE AT: www.vantagetravel.com/fww15 Additional Online Content YOUR DELUXE CRUISE SHIP Facebook The ms River Discovery II, a 5-star ship built exclusively for Vantage travelers, will be your home for the cruise portion of your journey. Enjoy spacious, all outside staterooms, a state- of-the-art infotainment system, and more. For complete details, visit our website. www.vantagetravel.com/discoveryII View our online video to learn more about our #1 river cruise. -

Burgundy Beaujolais

The University of Kentucky Alumni Association Springtime in Provence Burgundy ◆ Beaujolais Cruising the Rhône and Saône Rivers aboard the Deluxe Small River Ship Amadeus Provence May 15 to 23, 2019 RESERVE BY SEPTEMBER 27, 2018 SAVE $2000 PER COUPLE Dear Alumni & Friends: We welcome all alumni, friends and family on this nine-day French sojourn. Visit Provence and the wine regions of Burgundy and Beaujolais en printemps (in springtime), a radiant time of year, when woodland hillsides are awash with the delicately mottled hues of an impressionist’s palette and the region’s famous flora is vibrant throughout the enchanting French countryside. Cruise for seven nights from Provençal Arles to historic Lyon along the fabled Rivers Rhône and Saône aboard the deluxe Amadeus Provence. During your intimate small ship cruise, dock in the heart of each port town and visit six UNESCO World Heritage sites, including the Roman city of Orange, the medieval papal palace of Avignon and the wonderfully preserved Roman amphitheater in Arles. Tour the legendary 15th- century Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune, famous for its intricate and colorful tiled roof, and picturesque Lyon, France’s gastronomique gateway. Enjoy an excursion to the Beaujolais vineyards for a private tour, world-class piano concert and wine tasting at the Château Montmelas, guided by the châtelaine, and visit the Burgundy region for an exclusive tour of Château de Rully, a medieval fortress that has belonged to the family of your guide, Count de Ternay, since the 12th century. A perennial favorite, this exclusive travel program is the quintessential Provençal experience and an excellent value featuring a comprehensive itinerary through the south of France in full bloom with springtime splendor. -

Eurostar, the High-Speed Passenger Rail Service from the United Kingdom to Lille, Paris, Brussels And, Today, Uniquely, to Cannes

YOU R JOU RN EY LONDON TO CANNES . THE DAVINCI ONLYCODEIN cinemas . LONDON WATERLOO INTERNATIONAL Welcome to Eurostar, the high-speed passenger rail service from the United Kingdom to Lille, Paris, Brussels and, today, uniquely, to Cannes . Eurostar first began services in 1994 and has since become the air/rail market leader on the London-Paris and London-Brussels routes, offering a fast and seamless travel experience. A Eurostar train is around a quarter of a mile long, and carries up to 750 passengers, the equivalent of twojumbojets. 09 :40 Departure from London Waterloo station. The first part of ourjourney runs through South-East London following the classic domestic line out of the capital. 10:00 KENT REGION Kent is the region running from South-East London to the white cliffs of Dover on the south-eastern coast, where the Channel Tunnel begins. The beautiful rolling countryside and fertile lands of the region have been the backdrop for many historical moments. It was here in 55BC that Julius Caesar landed and uttered the famous words "Veni, vidi, vici" (1 came, l saw, 1 conquered). King Henry VIII first met wife number one, Anne of Cleaves, here, and his chieffruiterer planted the first apple and cherry trees, giving Kent the title of the 'Garden ofEngland'. Kent has also served as the setting for many films such as A Room with a View, The Secret Garden, Young Sherlock Holmes and Hamlet. 10:09 Fawkham Junction . This is the moment we change over to the high-speed line. From now on Eurostar can travel at a top speed of 186mph (300km/h). -

Specially Selected Wines

Beaumond Cross Inn Restaurant with Rooms Specially Selected Wines 13 London Road Newark-on-Trent NG24 1TN 01636 703670 France | Languedoc & Mâcon Collin Bourisset t the crossroads of Burgundy and Beaujolais, in Crêches sur Saône, lies the rolling estate of A Collin Bourisset. As one of the oldest and most reputable houses in Beaujolais, Collin Bourisset is known for producing some of the rarest wines from the best vineyards in the area. Their goal has always been to extract the finest Beaujolais and Mâconnais wines from the region to bring out the true excellence of French wine. Each of their wines are selected with extreme care, to protect the identity of the soil and the authenticity of every Bourisset vintage. Above: The Vineyards of Collin Bourisset Below: Sauvignon Blanc History The story of Collin Bourisset began in 1821, where its unique location allowed the estate to source grapes from the best vineyards in the surrounding area. Soon, the name Collin Bourisset became synonymous with the production of some of the rarest wines in France. Throughout the years, the Bourisset estate has maintained this reputation. Particularly when, in 1922, it became the exclusive distributors of the acclaimed “King of Cru Beaujolais”—Hospices de Romanèche Moulin a Vent. Today, Collin Bourisset’s single grape wines are renowned for being some of the best of their kind. The skill and experience of the winery is known to capture the essence of each vineyard’s terroir, allowing the quality of the grape to shine through to create truly exceptional wines. Bourisset’s vines White 125ml 175ml 250ml bottle Sauvignon Blanc £5.25 £6.50 £7.50 £22.50 Aromatic, crisp pear, apple and peach flavours are bright and lively, yet still remain soft and juicy on the palate. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

FALL/WINTER 2020-2021 WINE & SPIRITS PORTFOLIO FALL - WINTER 2020 / 2021 Dear Friends and Partners

FALL/WINTER 2020-2021 WINE & SPIRITS PORTFOLIO FALL - WINTER 2020 / 2021 Dear friends and partners, It has been almost 40 years since Baron Francois started importing wines in the United States. Founded by Adrien Baron in 1982 and taken over by the Lesgourgues Family since 2000, our company has been built with care, passion and dedication which continue to serve as our core. For the past ten years, Baron Francois has committed to diversifying its offering with no compromise on quality. We have recently added domestic and international wines along with boutique spirits to our portfolio with a special emphasis on sustainable, organic, and vegan practices. This development has established Baron Francois as a trus- ted and reputable wine and spirits importer and distributor based in New York City. It is with great pride and pleasure that I present to you this new catalog as it embodies our resilience and strength du- ring this pandemic. More than ever, it is important for us to show our appreciation and commitment to our customers, suppliers, and business partners and, thereby creating a complete portfolio that showcases our company’s vision and strategy. We hope this will serve as a tool to communicate with our long-time and future clients the quality of our wine and spirits selection. More than a multi-page catalog, this is a larger story that tells the history of multi-generational fami- lies whose talents and exceptionally diverse terroir created these hidden gems. Thank you all for your ongoing support and loyalty. May you discover your next favorite sip through these beautiful pages, specially designed for you! In appreciation of your business and partnership, Frédéric Goossens 4 5 Legend SUMMARY FEMALE WINEMAKER SPARKLING WINES This estate winemaking is led by a woman. -

French Wine Scholar

French Wine Scholar Detailed Curriculum The French Wine Scholar™ program presents each French wine region as an integrated whole by explaining the impact of history, the significance of geological events, the importance of topographical markers and the influence of climatic factors on the wine in the the glass. No topic is discussed in isolation in order to give students a working knowledge of the material at hand. FOUNDATION UNIT: In order to launch French Wine Scholar™ candidates into the wine regions of France from a position of strength, Unit One covers French wine law, grape varieties, viticulture and winemaking in-depth. It merits reading, even by advanced students of wine, as so much has changed-- specifically with regard to wine law and new research on grape origins. ALSACE: In Alsace, the diversity of soil types, grape varieties and wine styles makes for a complicated sensory landscape. Do you know the difference between Klevner and Klevener? The relationship between Pinot Gris, Tokay and Furmint? Can you explain the difference between a Vendanges Tardives and a Sélection de Grains Nobles? This class takes Alsace beyond the basics. CHAMPAGNE: The champagne process was an evolutionary one not a revolutionary one. Find out how the method developed from an inexpert and uncontrolled phenomenon to the precise and polished process of today. Learn why Champagne is unique among the world’s sparkling wine producing regions and why it has become the world-class luxury good that it is. BOURGOGNE: In Bourgogne, an ancient and fractured geology delivers wines of distinction and distinctiveness. Learn how soil, topography and climate create enough variability to craft 101 different AOCs within this region’s borders! Discover the history and historic precedent behind such subtle and nuanced fractionalization. -

France: Vineyards of Beaujolais

VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com France: Vineyards of Beaujolais Bike Vacation + Air Package Imagine cycling into the tranquil heart of Beaujolais, where the finest wines and most sublime cuisine greet you at every turn. Our inn-to-inn Self-Guided Bicycling Vacation through Beaujolais wine country reveals this storied region, with a wide choice of rides on traffic-free rural roads, through gently rolling vineyards and into authentic, timeless villages. Coast into Chardonnay, where the namesake wine was born. Explore the charming hamlets of Pouilly-Fuissé, Saint-Amour and Romaneche-Thorins. Step back in time as you explore prehistoric sites, Roman ruins, the medieval abbey of Cluny and villages carved from golden-hued stone. Along the way, experience memorable stays at a boutique city hotel and at stunning historic châteaux, where surrounding vineyards produce delicious wines and award-winning chefs serve the finest in French gastronomy. Cultural Highlights 1 / 10 VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com Cycle among the iconic vineyards of Beaujolais, coasting through charming wine villages producing some of France’s great wines Explore the renowned wine appellations and stunning stone villages of Pouilly-Fuissé, Saint- Amour and Romaneche-Thorins Ride into Cluny, once the world’s epicenter of Christianity, and view its 10th-century abbey Pedal to the Rock of Solutré, a striking limestone outcropping towering over vineyards and a favorite walking destination of former President Mitterand Take a spin among Southern Beaujolais’ 15th-century villages of golden stone, the Pierres dorées, constructed of luminescent limestone Sample fine Chardonnays when you pause in the village that gave the white wine its name Savor the luxurious amenities and stunning settings of two four-star Beaujolais chateaux, where gourmet meals and home-produced wines elevate your vacation What to Expect This tour offers a combination of easy terrain and moderate hills and is ideal for beginner and experienced cyclists. -

Travel to Provence & the Rhône Valley with Kevin White Winery

AN EXCLUSIVE JOURNEY PROVENCE & THE RHÔNE VALLEY Past Departure: April 9 – 16, 2018 14 8 / 7 17 GUESTS DAYS / NIGHTS MEALS Savor the flavors of the world’s most renowned wine regions. Discover the gourmand’s paradise of Lyon and enjoy cooking classes and traditional French delicacies in Provence. See treasured UNESCO World Heritage sites and explore some of France’s most picturesque landscapes and cities. Experience the French joie de vivre like you never expected! 206.905.4260 | [email protected] | https://experi.com/kevinwhitewinery/ | 1 MON, APR 9 DAY 1 MARSEILLE Land in the Marseille Provence Airport, and take a private transfer to a luxe Provençal farmhouse in the heart of the Luberon Valley. BONNIEUX Enjoy the chateau’s supreme comfort and relaxation. Meet the owner and Michelin starred chef and explore the grounds together, including his prized lush garden filled with wild herbs and edible flowers of the Luberon. Taste and smell the native herbs while chatting with the chef. After, sip aperitifs poolside with the group before dinner. Enjoy dinner served at the hotel prepared by its Michelin-starred chef. Bon Appétit! Dinner Overnight at Domaine de Capelongue Image not found or type unknown TUE, APR 10 DAY 2 CHÂTEAUNEUF-DU-PAPE Travel to the renowned wine region of Châteauneuf-du-Pape where vineyards cover more than 7,900 acres of land. Strict Appellation d'origine contrôlée rules allow 18 varieties of red and white wines to be produced. Enjoy a private tour and tasting at a boutique winery and learn about the region's terroir. -

The Ten Crus of Beaujolais

Tasting Notes ~ The Ten Crus of Beaujolais Saturday 16th November 2013 Accompanied by some saute’ saucissons chez Ecuyer Gordon & Riona Leitch followed by a supper of Coq au Vin de Beaujolais THE APERITIF CLAIRETTE DE DIE TRADITION - comes from Die in the Drome Department in the Rhone Valley. Made with Moscatel grapes by a form of Methode Champenoise - the wine is fermented slowly at low temperatures for several months, then filtered and bottled. Once bottled, the wine starts to warm up and the fermentation process starts again naturally, creating carbon dioxide gas as a by-product, which creates bubbles in the wine. The sediment at the bottom of the bottles is removed by decanting and filtering the wine in a pressurised container to retain the effervescence, and the wine is bottled again in fresh bottles. Wine made by this method must have it stated on the label. (source - Wikipedia) Purchased from CARREFOUR (CALAIS) – about £6.00 bottle, very limited availability in the UK although Manson Fine Wines shipped this to Inverness in the seventies. THE TASTING For those who cannot taste a lot of red wine or take none at all there is a Beaujolais Blanc for your enjoyment. This will also be the first wine of the tasting The tasting will really test our senses in every respect. It is a tasting that would normally be conducted only by professionals in the trade as it embraces 10 red wines from the same grape – and only one grape – the Gamay – We will be tasting consecutive vintages from neighbouring sub-areas, maybe even neighbouring vineyards. -

Springtime in Provence Burgundy ◆ Beaujolais Cruising the Rhône and Saône Rivers

SPRINGTIME IN PROVENCE BURGUNDY ◆ BEAUJOLAIS CRUISING THE RHÔNE AND SAÔNE RIVERS Beaune Deluxe Small River Ship Chalon-sur-Sa6ne e SWITZERLAND n r ô e a iv S R Geneva FRANCE M!con Beaujolais Chamonix Lyon Mont Blanc Tournon Tain-l’Hermitage Pont Du Gard e r e n v ô i h Orange R UNESCO R World Heritage Site Ch/teauneuf-du-Pape Avignon Cruise Itinerary Arles Aix-en-Provence Land Routing Mediterranean Marseille Sea Air Routing Join this exclusive, nine-day French sojourn in world-famous Provence and in the Burgundy and Beaujolais wine regions during springtime, the best Itinerary time of year to visit. Cruise from historic Lyon May 8 to 16, 2019 to Provençal Arles along the fabled Rhône and Lyon, Marseille, Beaune, Tournon, Orange, Saône Rivers aboard the exclusively chartered, Pont du Gard, Avignon, Arles deluxe Amadeus Provence, launched in 2017. Day Dock in the heart of port towns and visit the 1 Depart the U.S. wonderfully preserved Roman Amphitheater in Arles, the medieval Papal Palace of Avignon, the Roman city 2 Lyon, France/Embark Amadeus Provence of Orange and the legendary Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune. 3 Chalon-sur-Saône for Beaune/Mâcon for Beaujolais Enjoy a walking tour of Lyon, France’s gastronomique gateway, and an excursion to the Beaujolais vineyards 4 Lyon for a private wine tasting at the Château Montmelas. 5 Tournon-sur-Rhône and Tain-l’Hermitage The carefully designed Pre-Cruise Option features 6 Saint-Étienne-des-Sorts for Orange and Pont du Gard/ cosmopolitan Geneva, Switzerland, and the Chateauneuf du Pape beautiful town of Chamonix, France, at the base of spectacular Mont Blanc. -

Appendix 2 Trademarks Indicating a Place of Origin of Wines Or Spirits Of

Appendix 2-1 [The Patent Office Gazette (public notice) issued on June 23, 1995] Trademarks Indicating a Place of Origin of Wines or Spirits of WTO Member Countries as Stipulated in Article 4(1)(xvii) of the Trademark Act The following appellations of origin of wines or spirits that are registered internationally under Article 5(1) of the “Lisbon Agreement for the Protection of Appellations of Origin and their International Registration (1958)” shall be deemed to fall under a mark indicating a place of origin of wines or spirits in a member of the WTO prohibited to be used on wines or spirits not originating in the region of that member referred to in Article 4(1)(xvii) of the Trademark Act that entered into effect on July 1, 1995, except when the international registration has been cancelled or when there are other special reasons. Herein is the announcement to that effect. (Lists on public notice are omitted) (Explanation) In utilizing Appendix 2 1. Purport for preparing this material In the recent revision of the Trademark Act pursuant to the Act for Partial Revision of the Patent Act, etc. (Act No. 116 of 1994), Article 4(1)(xvii) was newly added in accordance with Annex IC “Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement)” of the “Marrakech Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO),” which accords additional protection to geographical indications of wines and spirits. This material, which was prepared as examination material related to Article 4(1)(xvii) of the Trademark Act, provides