Ciuptiol T\((0 Dhuli^: DISTRICT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educational Development Index Maharashtra 2011-12

Educational Development Index Maharashtra 2011-12 December, 2012 Contents S.No. Subject Page number 1.0 Background and Methodology 3 2.0 Status of Maharashtra state at National level in EDI 4 3.0 EDI calculation in Maharashtra state 7 4.0 Analysis of district wise Educational Development Index (EDI), 2011-12 8 5.0 Analysis of block wise Educational Development Index (EDI), 2011-12 14 6.0 Analysis of Municipal Corporation wise Educational Development Index (EDI), 20 2011-12 Annex-1 : Key educational indicators by Districts, 2011-12 23 Annex-2 : Index value and ranking by Districts, 2011-12 25 Annex-3 : Key educational indicators by blocks, 2011-12 27 Annex-4 : Index value and ranking by blocks, 2011-12 45 Annex-5 : Key educational indicators by Municipal Corporations , 2011-12 57 Annex-6 : Index value and ranking by Municipal Corporations, 2011-12 58 Educational Development Index, 2011-12, Maharashtra Page 1 Educational Development Index, 2011-12, Maharashtra 1.0 Background and Methodology: Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), Government of India and the National University of Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA), New Delhi initiated an effort to compute Educational Development Index (EDI).In year 2005-06, MHRD constituted a working group to suggest a methodology (which got revised in 2009)for computing EDI. The purpose of EDI is to summarize various aspects related to input, process and outcome indicators and to identify geographical areas that lag behind in the educational development. EDI is an effective tool for decision making, i.e. it helps in identifying backward geographical areas where more focus is required. -

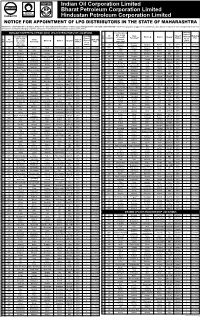

Indian Oil Corporation Limited Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited

Indian Oil Corporation Limited Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited NOTICE FOR APPOINTMENT OF LPG DISTRIBUTORS IN THE State OF MAHARASHTRA INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD (IOCL), BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LTD (BPCL) and HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LTD (HPCL) proposes to appoint LPG distributors under various categories at locations specified below from amongst the candidates belonging to different categories mentioned therein in the State of (name of the State): DURGAM KSHETRIYA VITRAK (DKV) LPG DISTRIBUTORSHIP LOCATIONS Location (along Security with details Deposit Security Sr. Oil Gram Type of Marketing Location (along of Locality Block* @ District Category** (Amount Deposit No. Company Panchayat* Market Plan with details wherever Rs. in Sr. Oil Gram Type of (Amount Marketing of Locality Block* @ District Category** applicable) Lakhs) No. Company Panchayat* Market Rs. in Plan wherever Chinchave Chinchave Lakhs) 96 IOC Malegaon Nashik SC 2 2017-18 applicable) (Galane) (Galane) DKV 1 IOC Khirvire Khirvire Akole Ahmednagar Open DKV 4 2017-18 97 HPC Nimgaon Nimgaon Malegaon Nashik Open(W) DKV 4 2017-18 2 IOC Hatru Hatru Chikhaldara Amravati OBC DKV 3 2017-18 98 IOC Tingri Tingri Malegaon Nashik Open DKV 4 2017-18 3 IOC Ghodgaon Ghodgaon Chopda Jalgaon ST DKV 2 2017-18 99 BPC Vehelgaon Vehelgaon Nandgaon Nashik OBC DKV 3 2017-18 4 BPC Ghuikhed Ghuikhed Chandur Railway Amravati Open DKV 4 2017-18 100 IOC Thangaon Thangaon Sinnar Nashik ST(W) DKV 2 2017-18 5 IOC Jalalkheda Jalalkheda Narkhed Nagpur -

District Census Handbook, Dhule

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK DHULE Compiled by THE MAHARASlITRA CENSUS DIRECTORATE BOMBAY Price : Rs. 30.00 PRINTED IN INDIA BY THE MANAGER. YERA VDA PRISON PRESS, PUNE AND PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTOR, GOVERNMENT PRINTING AND STATIONERY, MAHARASHTRA STATE, BOMBAY-400 004 1985 '": ~co ":;: 0 • u © • 0 B .~ .g Q: :r • cr "0 @ I '1 1: >: 1~ '" I w '" " .....J . 0 • ~ ~ e 0 ::> I c '"~ <l: 0 · ::I: e i 0 a:: Ol 0 0- g~ 2" 0 z." ] ~ I ." DC Vl .2 0 Q ; 0 0 ~ ~ 0 0 1j <l: cr 0 :l"Pj "0 .c C ~ .. t- g ~ a:: 0 ~ ,. .c § ;~ <l: 0 6 ,. E '" I U ~ ~ ~ ~ 0 ~ ~ Vi < B-1 <l: . ! ~ ; ~ · Vi 0> ~ i < . ~~ ~ ;3 0 cr I C "0 · ~ C 2 ~ ·0 ~ 0 i 0 0";' x· t- s ('; c. 0 0 ~ . o • If) ,f~ ~2 ·~ t I V> § ;> ~ ~I '" cii Ii: :0" £ a · V> '" 0 ~ 1- " () ..(- /r ,9 tl' 8- 'J Ir J " & J 0 S <:) i" ~ I U- ";, 0 "r % ~ "'(j.\6,;~r§\ ,\oc.: ~'r::/l.O «- po.~tc.~ " ~ .. -:' ..l.. le ~ .:t () If) 'Of <l: <! ~ ... (J 0: 0 ... .£ i, "0 '"" </I 1 <!> ,.0 ~ 0 ~ .> I ':i , l, V> "8" .c ~r·,-- l' "0 .. ,.. i .~ ~ I'. ~ s:::" ~ "0 i'" 1 .c .c ~ "~ " U; 0 " a E ~ 0- ~ l' ::. ] I "0 ~ :r :; Vl . a :;: , VI ~ r e-'" (\ ~~ ..] MOTIF 'The Bhils of Maharashtra are mainly concentrated in Dhule district. They have kng history since ancient times. The earliest mention of their name occurs in the Ramayana and the Maha bharata. Bhils possibly belong 10 a proto Mediterranean race who spread far and wide when a climatic crisis occurred in the gral>s steppes 0 f the Sahara. -

Chapter 1 Chapter 1

1 Chapter 1 Khandesh adivasis further pushed to impoverisation hule, Nandurbar and Jalgaon districts make up the Khandesh region of D Maharashtra. Khandesh is bounded on the west by Gujarat in the east by the Vidarbha part of Maharashtra, in the south by Nasik district and the Marathwada part of Maharashtra 1 and in the north by Madhya Pradesh. The Tapi basin lies in the north-west of Dhule district now comprising Shahada and Talode talukas. It forms a distinct topographical unit, delimited from neighbouring state, Madhya Pradesh by Satpura range and from the south by Satmala hills range. An arc of Sahyadris or Western Ghats stretches in the easterly direction. Before 1 July 1998 Nandurbar was part of the larger Dhule district. Dhule was known as the West Khandesh whereas Jalgaon was known as the East Khandesh. 2 Presently Dhule, Nandurbar and Jalgaon districts comprise of four, six and thirteen administrative blocks respectively. Map of Khandesh Region 1 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14672715.1981.10409913 2 https://infogalactic.com/info/Nandurbar_district 2 Khandesh region lies just south of the great belt of mountains and forests that girdles India, and leads directly into the rich cotton tracts of north east Maharashtra. The strip of land between Akkalkuwa and Talode talukas of Nandurbar district and the Tapi River in the North connect Navapur and Nandurbar talukas of Nandurbar district and in the South form a part of Gujarat. In 1972, a large dam was built on the Tapi River at Ukai in Gujarat displacing hundreds of adivasis. -

GOVERNMENT of MAHARASHTRA Department of Agriculture

By Post/Hand GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA Department of Agriculture To, M/s. VAISHANAVI AGRO BIOTECH PVT LTD, Plot No 59, Baban Phelvan Nagar, Talode (m Cl), Pin: 425442, Tahsil: Talode, District: Nandurbar, State: Maharashtra Sub: Issuing New Fertiliser License No. LCFDW10010837. Validity: 04/06/2016 to 03/06/2019 Ref : Your letter no. FWD377555 dated : 25/05/2016 Sir, With reference to your application for New Fertilizer license. We are pleased to inform you that your request for the same has been granted. License No. : LCFDW10010837 dated :04/06/2016. Valid For : 04/06/2016 to 03/06/2019 is enclosed here with. This license is issued under Fertilizer Control Order,1985 The terms and conditions are mentioned in the license. You are requested to apply for the renewal of the license on or before 03/06/2019. Responsible Person Details: Name: Rajendra Himmatsing Rajput, Age:44, Designation: Propritor Office Address: At Post Mod, Mod, Taluka:Talode, District: Nandurbar, State: Maharashtra, Pincode: 425442, Mobile: 9423943490, Email: [email protected] Name: Rajendra Himmatsing Rajput, Age:44, Designation: Propritor Residential Address: At Post Mod, Mod, Taluka:Talode, District: Nandurbar, State: Maharashtra, Pincode: 425442, Mobile: , Email: Chief Quality Control Officer Commissionerate Of Agriculture Pune Encl. :License. Copy to 1) Divisional Joint Director of Agriculture(All) 2) District Superintendent Agriculture Officer(All) 3) Agriculture Developement Officer(All) Original GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA Wholesale Dealer State Level FORM 'A2' ACKNOWLEDGEMENT (See Clause 8(3)) License No. : LCFDW10010837 Date of Issue : 04/06/2016 Valid From : 04/06/2016 Valid Upto : 03/06/2019 1. Received from M/s Vaishanavi Agro Biotech Pvt Ltd a complete Memorandum of Intimation along with Form O,fee of Rs. -

Shahada Assembly Maharashtra Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/MH-002-0118 ISBN : 978-93-86662-58-3 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 127 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency - (Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency - (Vidhan Sabha) in 3-8 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency - (Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2014-AE Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 9-19 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 20-21 Population -

(W.C~F Kt~Ri<&I. Ddncf}

- AI<..RA N I /_\,{ oJ\h·J.. (W.c~f Kt~ri<&I. ddncf} No. DCXL\l-New Serie~ PAPERS RELATING TO THE ORIGINAL. SETTLEMENT OF THE AKRANI MAHAL OF THE WEST KHANDESH DISTRICT [Price-A.unas 10 or ls. ld.J BOMBAY PRINTED AT THE GOVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS ' 1930 the (iroup · and Rating as s fiovernmenr. IEfllflrE. ...................... ,..................... Hax-~ofe3. 11o oF Yillo~ .. !:' .. ... ,. ................. e i .. "" ............... 1 , .........,..... •·· ........... B:l 6roup ....... I ... '--------- 0-12-0 .............. 26 ........ .. ............. til ............. ............. x Group ......II .. I '--------- 0-8-0 ____________ 41 ,_,.......... .. .,,,.p,' .......... ,.,....,.. '*" ...... I'T. Akroni HohaL-- 6 7 ......., ..... ... .. ................ , ~"'""'"'""'' ........... o. • ... 1 ,, ~- ' " '""' ' .............. ·J'· Road:s•.• -----------· ,...fl,.,... ........................ f" ......... ,, ................ -·-·- .. ......... ... , ..... ........... I ........ ................ r11 .. ...._ ., ........... N.D . ....... , · · ......... ....... I.D ..._ .. · .......... Ml - MN ~ ...... .. .. .... 1/, . .. ..... , ......... II .,. ........ ' ,,.,.,.,,. 11~1 L\ IIMfl .... .. " ........ II. .. T. .. J. .. "" .) ...-..,..., ............ ,.......... fl>,,,, ... -..,.... ... ... -... ,.,..," ·-···' ........ ,.. ··· ' -.::.=:~ -__...... _ ... "* "'. "' ... •• ~~· I~· " IW llfit4~ a,~ , ' a • •- ···• '"'r:=!:A.tr==-..~= ,, ,a I I ,...,OIIIMUI , •11011111 , -.. MIAN .... , .. ... ... • arl)a 1 z • •ll'•. ---..-·-··-,J• .. Ill~,,. -

Village Map Taluka: Shahade District: Nandurbar

Village Map Taluka: Shahade Akrani District: Nandurbar Nagziri Ranipur Madhya Pradesh State Nimbardi (F.V.) Dara Navagaon (F.V.) PimpraniChirde Virpur Ganor µ Rampur Khargaon Lakkadkot Ambapur 3.5 1.75 0 3.5 7 10.5 Madkani km Akaspur Nandya Talavadi Adgaon Kansai Fattepur Isalampur Bahirpur Kusumwade Tawalai Biladi-t-haveliKhed-digar Bhute Mubarakpur Amode Kudhavad Location Index Anakwade Shrikhed Shirud-t-haveli Kochare Kanadi-t-haveli Ukhalshem Javade-t-borad Sulwade Raikhed Kurangi Jam Welavad Umarti Mhasavad Sultanpur Jaavade-t-haveli Pimplod Bhortek Wadi Ozarte District Index Nandurbar Lachore Talode Chikhali Bk Bhandara Pimpri Navanagar Amravati Nagpur Gondiya Budigavhan Chikhali Kh.Wagharde Titari Dhule Kalmadi-t-borad Javkhede Damalde Jalgaon Aurangpur Godipur Akola Wardha Thengche BramhanpuriBhagapur Buldana Vadgaon Kothali-t-haveli Junavane Nashik Washim Chandrapur Awage Kalmad-t-haveli Shahane Yavatmal Padalde-bk Gogapur Palghar Aurangabad Navalpur Jalna Gadchiroli Tarhadi-t-borad ChandsailiPadalde-kh. Hingoli Sonval-t-borad Pari Tuki Tidhare Thane Ahmednagar Parbhani Mandane Mumbai Suburban Nanded Bid Mohinde-t-haveli Sonval-t-haveli Lohare Mumbai Varde Asus Kavalith Pune Raigarh Bidar Karankheda Alkhed Latur Hol Asalod Osmanabad Waghode Dhamlad Kalsadi TembhaliHol-gujari Sawakheda Karjot Satara Solapur Untavad Kamaravad Bhongra Dudhkheda Langadi-bhavani Ratnagiri Vaijali Tikhore Sangli Katharde Kh New-aslod LonkhedaPurushottamnagar Bhade Pimparde Maharashtra State Nandarde Katharde-digar Maloni Kolhapur Bhulane Sindhudurg -

Levels of Disparity in Literacy of Scheduled Tribes of Nandurbar District

International Journal of Applied Research 2016; 2(2): 236-240 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 Levels of disparity in literacy of scheduled tribes of IJAR 2016; 2(2): 236-240 www.allresearchjournal.com Nandurbar district: A spatial analysis Received: 27-12-2015 Accepted: 30-01-2016 RC Ahire, Dr. SR Chaudhari RC Ahire Assistant Professor, Abstract Department of Geography, Late Annasaheb R. D. Deore, Indian society suffers from gender disparity in literacy, health care and employment. Higher illiteracy Arts and Sci. College, Mhasadi, among scheduled tribes particularly among ST females resulted higher gender disparity in literacy. Tal. Sakri, Dist. Dhule. Their knowledge about ecology, community cleanliness, raising children, managing households under (Maharashtra) unstable circumstances etc. amounted to nothing mainly because of their lack of literacy and education. Lack of education among tribes stands in the way of their employability. Hence, we find the importance Dr. SR Chaudhari of the study of literacy and education in the tribal dominated district like Nandurbar. This paper Former Principal, analyses the levels of disparity in literacy of Scheduled Tribes (STs) in Nandurbar district, which is one Pratap College, Amalner, of the tribal dominated districts of Maharashtra. Literacy plays a very crucial role in the social and Dist. Jalgaon (Maharashtra) economic development in a country. A low level of literacy in a population retards the progress along the path of social and economic development and political power. Illiteracy, particularly among female in a society, results in stagnation of technology, social and cultural lags weakness, national security and overall staginess of the economic progress. -

NASHIK District : NASHIK Region : NASHIK ITI Name : GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, NASHIK, TAL: NASHIK, DIST: NASHIK

Directorate of Vocational Education and Training, Maharashtra State ITI Directory for Admission in Session 2017-18 ITI Code : 2755161018 Taluka : NASHIK District : NASHIK Region : NASHIK ITI_Name : GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, NASHIK, TAL: NASHIK, DIST: NASHIK Address : BABUBHAI RATHI CHOWK, TRAMBAK ROAD, SATPUR City : SATPUR Phone No : 02532350116 ITI Category : GENERAL TRADE NAME UNIT CATEGORY IMC UNIT INTAKE IMC Seats Carpenter Govt ITI – General No 52 0 Computer Operator and Programming Assistant Govt ITI – General No 78 0 Draughtsman Civil Govt ITI – General No 26 0 Draughtsman Mechanical Govt ITI – General No 42 0 Electrician Govt ITI – General No 63 0 Electronics Mechanic Govt ITI – General No 26 0 Fitter Govt ITI – General No 84 0 Foundryman Govt ITI – General No 42 0 Information & Communication Technology System Govt ITI – General No 26 0 Maintenance Instrument Mechanic Govt ITI – General No 52 0 Machinist Govt ITI – General No 64 0 Machinist Grinder Govt ITI – General No 48 0 Mason (Building Constructor) Govt ITI – General No 26 0 Mechanic Diesel Govt ITI – General No 63 0 Mechanic Machine Tools Maintenance Govt ITI – General No 42 0 Mechanic Motor Vehicle Govt ITI – General No 21 0 Mechanic Refrigeration & Air Conditioner Govt ITI – General No 26 0 Operator Advance Machine Tools Govt ITI – General No 16 0 Plastic Processing Operator Govt ITI – General No 63 0 Plumber Govt ITI – General No 26 0 Pump Operator cum Mechanic Govt ITI – General No 21 0 Sheet Metal Worker Govt ITI – General No 42 0 Stenography & Secretarial Assistant (English) Govt ITI – General No 52 0 Tool & Die Maker (Press Tools, Jigs & Fixtures) Govt ITI – General No 84 0 Turner Govt ITI – General No 96 0 Welder Govt ITI – General No 63 0 Wireman Govt ITI – General No 63 0 Total Seats for Admission 2017 1307 0 All Trade and Unit Proposed by Regional Office, NASHIK Page 1 of 37 This is Indicative Directory. -

Districtwise Details of Village Allocation for Population Between 1600-2000 Under Fi Plan for March 2013

DISTRICTWISE DETAILS OF VILLAGE ALLOCATION FOR POPULATION BETWEEN 1600-2000 UNDER FI PLAN FOR MARCH 2013. Sr District Block Allotted Village Gram Village Populati Allotted to Bank Branch Panchayat Census on Code Census 2001 1 Ahmednagar Nagar Hingangaon 1920 Allahabad Bank Jakhangaon 2 Ahmednagar Nagar Khatgaon Takli 1783 Allahabad Bank Jakhangaon 3 Ahmednagar Sangamner Ozar Kh. 1788 Allahabad Bank Kankapur 4 Ahmednagar Newasa Soundala 1806 Bank of Baroda bhende 5 Ahmednagar Newasa Wanjoli 1832 Bank of Baroda Ghodegaon 6 Ahmednagar Pathardi Karodi 1654 Bank of Baroda Pathardi 7 Ahmednagar Newasa Khampimpri 1653 Bank of Baroda Pravarasangam 8 Ahmednagar Newasa Babhulkhede 1734 Bank of Baroda Salabatpur 9 Ahmednagar newasa Galnimb 1715 Bank of Baroda Salabatpur 10 Ahmednagar newasa Gopalpur 1722 Bank of Baroda Salabatpur 11 Ahmednagar newasa Jalke Bk. 1921 Bank of Baroda Salabatpur 12 Ahmednagar Sangamner Palaskhede 1841 Bank of Baroda Sangamner 13 Ahmednagar Kopargaon Dauch Kh. 1908 Bank of India Chandekasare 14 Ahmednagar Kopargaon Patoda 1852 Bank of India Kopargaon 15 Ahmednagar Nagar Bhorwadi 1717 Bank of Maharashtra Akolner 16 Ahmednagar Shrirampur Waladgaon 1744 Bank of Maharashtra Belapur 17 Ahmednagar Shevgaon Prabhuwadgaon 1752 Bank of Maharashtra Chapadgaon 18 Ahmednagar Shevgaon Ranegaon 1820 Bank of Maharashtra Chapadgaon 19 Ahmednagar Shevgaon Shingori 1603 Bank of Maharashtra Chapadgaon 20 Ahmednagar Shevgaon Warkhed 1626 Bank of Maharashtra Chapadgaon 21 Ahmednagar Pathardi Wadgaon 1733 Bank of Maharashtra Chinchpurpangul 22 Ahmednagar Rahata Dighi 1631 Bank of Maharashtra Chitali 23 Ahmednagar Kopargaon Ghoyegaon 1601 Bank of Maharashtra Dahigaonbolka 24 Ahmednagar Jamkhed Telangashi 1914 Bank of Maharashtra Jategaon 25 Ahmednagar Nagar Imampur 1973 Bank of Maharashtra Jeur 26 Ahmednagar Nagar Khospuri 1662 Bank of Maharashtra Jeur 27 Ahmednagar Kopargaon Ghari 1603 Bank of Maharashtra Kopargaon 28 Ahmednagar Newasa Antarwali 1814 Bank of Maharashtra Kukana 29 Ahmednagar Newasa Sultanpur Bk. -

É´Émééçiéò±É =¨Éän Ù´ÉÉ®Úé

Page 1 +xÉÖºÉÚÊSÉiÉ IÉäjÉÉiÉÒ±É +xÉÖºÉÚÊSÉiÉ VɨÉÉiÉÒ |É´ÉMÉÉÇiÉÒ±É =¨Éänù´ÉÉ®úÉÆSÉÒ ºÉ´ÉǺÉÉvÉÉ®úhÉ ÊxÉEòÉ±É ªÉÉnùÒ xÉÉʶÉEò ºÉƦÉÉMÉ, xÉÆnÖù®ú¤ÉÉ®ú ÊVɱ½þÉ. Sl no Registration No Candidate Name Address DOB Gender Category Handi Ex- Project Earthquake Part-time Sports Non- Marks capped service affected affected employee man creamy obtained type men layer 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1 P_AGRI_KS_0038760 GIRISH BHAURAO KOKANI AT MALVAN POST SHRAWANI NANDURBAR MAHARASHTRA 1995-02-28 MALE ST 139.09 AT POST VADGAON TAL SHAHADA DIST NANDURBAR VADGAON NANDURBAR 2 P_AGRI_KS_0015681 HIRALAL SUBHASH PAWARA 1995-08-01 MALE ST 137.06 MAHARASHTRA 3 P_AGRI_KS_0013236 AMIT MALJI NAIK AT POST ANJANE TAL NAWAPUR DIST NANDURBAR ANJANE NANDURBAR MAHARASHTRA 1990-09-01 MALE ST 135.03 AT GANOR PO MUBARAKPUR TAL SHAHADA DIST NANDURBAR GANOR NANDURBAR 4 P_AGRI_KS_0040525 SANTOSH DAGA VALVI 1990-11-01 MALE ST 134.01 MAHARASHTRA 5 P_AGRI_KS_0052689 Sachin Gulabsing Valvi At- vyahur post -Dhulwad Vyahur NANDURBAR MAHARASHTRA 1991-04-12 MALE ST 132.99 6 P_AGRI_KS_0012295 AKSHAY VASANT NAIK AT THANAVIHIR POST SHIRVE NANDURBAR MAHARASHTRA 1995-05-22 MALE ST 132.99 7 P_AGRI_KS_0029792 KALYANSING SUKALAL PAWAR AT BILADI T H POST RAIKHED BILADI T H NANDURBAR MAHARASHTRA 1990-10-22 MALE ST 131.98 8 P_AGRI_KS_0008022 SUSHILKUMAR NARAYAN KOKANI AT POST SHEHI TAL NAWAPUR DIST NANDURBAR SHEHI NANDURBAR MAHARASHTRA 1988-08-01 MALE ST 130.96 9 P_AGRI_KS_0038651 RAJANI BHAURAM KOKANI AT MALVAN POST SHRAWANI NANDURBAR MAHARASHTRA 1990-03-07 FEMALE ST 130.96 10 P_AGRI_KS_0022081