COGS 101A: Sensation and Perception 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MITOCW | 9: Receptive Fields - Intro to Neural Computation

MITOCW | 9: Receptive Fields - Intro to Neural Computation MICHALE FEE: So today, we're going to introduce a new topic, which is related to the idea of fine- tuning curves, and that is the notion of receptive fields. So most of you have probably been, at least those of you who've taken 9.01 or 9.00 maybe, have been exposed to the idea of what a receptive field is. The idea is basically that in sensory systems neurons receive input from the sensory periphery, and neurons generally have some kind of sensory stimulus that causes them to spike. And so one of the classic examples of how to find receptive fields comes from the work of Huble and Wiesel. So I'll show you some movies made from early experiments of Huble-Wiesel where they are recording in the visual cortex of the cat. So they place a fine metal electrode into a primary visual cortex, and they present. So then they anesthetize the cat so the cat can't move. They open the eye, and the cat's now looking at a screen that looks like this, where they play a visual stimulus. And they actually did this with essentially a slide projector that they could put a card in front of that had a little hole in it, for example, that allowed a spot of light to project onto the screen. And then they can move that spot of light around while they record from neurons in visual cortex and present different visual stimuli to the retina. -

The Roles and Functions of Cutaneous Mechanoreceptors Kenneth O Johnson

455 The roles and functions of cutaneous mechanoreceptors Kenneth O Johnson Combined psychophysical and neurophysiological research has nerve ending that is sensitive to deformation in the resulted in a relatively complete picture of the neural mechanisms nanometer range. The layers function as a series of of tactile perception. The results support the idea that each of the mechanical filters to protect the extremely sensitive recep- four mechanoreceptive afferent systems innervating the hand tor from the very large, low-frequency stresses and strains serves a distinctly different perceptual function, and that tactile of ordinary manual labor. The Ruffini corpuscle, which is perception can be understood as the sum of these functions. located in the connective tissue of the dermis, is a rela- Furthermore, the receptors in each of those systems seem to be tively large spindle shaped structure tied into the local specialized for their assigned perceptual function. collagen matrix. It is, in this way, similar to the Golgi ten- don organ in muscle. Its association with connective tissue Addresses makes it selectively sensitive to skin stretch. Each of these Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute, 338 Krieger Hall, receptor types and its role in perception is discussed below. The Johns Hopkins University, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218-2689, USA; e-mail: [email protected] During three decades of neurophysiological and combined Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2001, 11:455–461 psychophysical and neurophysiological studies, evidence has accumulated that links each of these afferent types to 0959-4388/01/$ — see front matter © 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. a distinctly different perceptual function and, furthermore, that shows that the receptors innervated by these afferents Abbreviations are specialized for their assigned functions. -

Center Surround Receptive Field Structure of Cone Bipolar Cells in Primate Retina

Vision Research 40 (2000) 1801–1811 www.elsevier.com/locate/visres Center surround receptive field structure of cone bipolar cells in primate retina Dennis Dacey a,*, Orin S. Packer a, Lisa Diller a, David Brainard b, Beth Peterson a, Barry Lee c a Department of Biological Structure, Uni6ersity of Washington, Box 357420, Seattle, WA 98195-7420, USA b Department of Psychology, Uni6ersity of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA c Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Gottingen, Germany Received 28 September 1999; received in revised form 5 January 2000 Abstract In non-mammalian vertebrates, retinal bipolar cells show center-surround receptive field organization. In mammals, recordings from bipolar cells are rare and have not revealed a clear surround. Here we report center-surround receptive fields of identified cone bipolar cells in the macaque monkey retina. In the peripheral retina, cone bipolar cell nuclei were labeled in vitro with diamidino-phenylindole (DAPI), targeted for recording under microscopic control, and anatomically identified by intracellular staining. Identified cells included ‘diffuse’ bipolar cells, which contact multiple cones, and ‘midget’ bipolar cells, which contact a single cone. Responses to flickering spots and annuli revealed a clear surround: both hyperpolarizing (OFF) and depolarizing (ON) cells responded with reversed polarity to annular stimuli. Center and surround dimensions were calculated for 12 bipolar cells from the spatial frequency response to drifting, sinusoidal luminance modulated gratings. The frequency response was bandpass and well fit by a difference of Gaussians receptive field model. Center diameters were all two to three times larger than known dendritic tree diameters for both diffuse and midget bipolar cells in the retinal periphery. -

The Visual System: Higher Visual Processing

The Visual System: Higher Visual Processing Primary visual cortex The primary visual cortex is located in the occipital cortex. It receives visual information exclusively from the contralateral hemifield, which is topographically represented and wherein the fovea is granted an extended representation. Like most cortical areas, primary visual cortex consists of six layers. It also contains, however, a prominent stripe of white matter in its layer 4 - the stripe of Gennari - consisting of the myelinated axons of the lateral geniculate nucleus neurons. For this reason, the primary visual cortex is also referred to as the striate cortex. The LGN projections to the primary visual cortex are segregated. The axons of the cells from the magnocellular layers terminate principally within sublamina 4Ca, and those from the parvocellular layers terminate principally within sublamina 4Cb. Ocular dominance columns The inputs from the two eyes also are segregated within layer 4 of primary visual cortex and form alternating ocular dominance columns. Alternating ocular dominance columns can be visualized with autoradiography after injecting radiolabeled amino acids into one eye that are transported transynaptically from the retina. Although the neurons in layer 4 are monocular, neurons in the other layers of the same column combine signals from the two eyes, but their activation has the same ocular preference. Bringing together the inputs from the two eyes at the level of the striate cortex provide a basis for stereopsis, the sensation of depth perception provided by binocular disparity, i.e., when an image falls on non-corresponding parts of the two retinas. Some neurons respond to disparities beyond the plane of fixation (far cells), while others respond to disparities in front of the plane of the fixation (near cells). -

The Retina and Vision

CHAPTER 19 The Retina and Vision The visual system is arguably the most important system through which our brain gathers information about our surroundings, and forms one of our most complex phys- iological systems. In vertebrates, light entering the eye through the lens is detected by photosensitive pigment in the photoreceptors, converted to an electrical signal, and passed back through the layers of the retina to the optic nerve, and from there, through the visual nuclei, to the visual cortex of the brain. At each stage, the signal passes through an elaborate system of biochemical and neural feedbacks, the vast majority of which are poorly, if at all, understood. Although there is great variety in detail between the eyes of different species, a number of important features are qualitatively conserved. Perhaps the most striking of these features is the ability of the visual system to adapt to background light. As the background light level increases, the sensitivity of the visual system is decreased, which allows for operation over a huge range of light levels. From a dim starlit night to a bright sunny day, the background light level varies over 10 orders of magnitude (Hood and Finkelstein, 1986), and yet our eyes continue to operate across all these levels without becoming saturated with light. The visual system accomplishes this by ensuring that its sensitivity varies approximately inversely with the background light, a relationship known as Weber’s law (Weber, 1834) and one that we discuss in detail in the next section. Because of this adaptation, the eye is more sensitive to changes in light level than to a steady input. -

Chromatic Mach Bands: Behavioral Evidence for Lateral Inhibition in Human Color Vision

Perception &: Psychophysics 1987, 41 (2), 173-178 Chromatic Mach bands: Behavioral evidence for lateral inhibition in human color vision COLIN WARE University ofNew Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada and Wll..LIAM B. COWAN National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Apparent hue shifts consistent with lateral inhibition in color mechanisms were measured, in five purely chromatic gradients, for 7 observers. Apparent lightness shifts were measured in achro matic versions of the same gradients, and a correlation was found to exist between the magni tude of the chromatic shifts and the magnitude ofthe achromatic shifts. The data can be modeled by a function that approximates the activity of color-sensitive neurons found in the monkey cor tex. Individual differences and the failure of some previous researchers to find the effect can be accounted for by differences in the function parameters for different observers. One of the intensity gradients used by Ernst Mach an achromatic component, chromatic shifts could be (1886/1967) to demonstrate what have become known as caused by a coupling to the achromatic effect through, "Mach bands" is graphed in Figure 1 (curve C). Ob for example, the Bezold-Briicke effect. They also argue servers of a pattern with this luminance profile report a that, because prolonged viewing was allowed, chromatic bright band at the point where the luminance begins to Mach bands may be an artifact ofsuccessive contrast and decline. As with others like it, thisobservation represents eye movements and not evidence for lateral interactions. one of the principal sources ofevidence for spatially in On the other side, those who find chromatic Mach bands hibitory interactions in the human visual system. -

Seeing in Three Dimensions: the Neurophysiology of Stereopsis Gregory C

Review DeAngelis – Neurophysiology of stereopsis Seeing in three dimensions: the neurophysiology of stereopsis Gregory C. DeAngelis From the pair of 2-D images formed on the retinas, the brain is capable of synthesizing a rich 3-D representation of our visual surroundings. The horizontal separation of the two eyes gives rise to small positional differences, called binocular disparities, between corresponding features in the two retinal images. These disparities provide a powerful source of information about 3-D scene structure, and alone are sufficient for depth perception. How do visual cortical areas of the brain extract and process these small retinal disparities, and how is this information transformed into non-retinal coordinates useful for guiding action? Although neurons selective for binocular disparity have been found in several visual areas, the brain circuits that give rise to stereoscopic vision are not very well understood. I review recent electrophysiological studies that address four issues: the encoding of disparity at the first stages of binocular processing, the organization of disparity-selective neurons into topographic maps, the contributions of specific visual areas to different stereoscopic tasks, and the integration of binocular disparity and viewing-distance information to yield egocentric distance. Some of these studies combine traditional electrophysiology with psychophysical and computational approaches, and this convergence promises substantial future gains in our understanding of stereoscopic vision. We perceive our surroundings vividly in three dimen- lished the first reports of disparity-selective neurons in the sions, even though the image formed on the retina of each primary visual cortex (V1, or area 17) of anesthetized cats5,6. -

MTTTS17 Dimensionality Reduction and Visualization

MTTTS17 Dimensionality reduction and visualization Spring 2020 Lecture 5: Human perception Jaakko Peltonen jaakko dot peltonen at tuni dot fi 1 Human perception (part 1) Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn't mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe. 2 Human perception (part 1) Most strikingly, a recent paper showed only an 11% slowing when people read words with reordered internal letters: 3 Human perception (part 1) 4 Human perception (part 1) 5 Human perception (part 1) 6 Human perception (part 1) 7 Human perception (part 1) 8 Human perception (part 1) 9 Human perception Human perception and visualization • Visualization is young as a science • The conceptual framework of the science of visualization is based on the human perception • If care is not taken bad designs may be standardized 10 Human perception Gibson’s affordance theory 11 Human perception Sensory and arbitrary symbols 12 Human perception Sensory symbols: resistance to instructional bias 13 Human perception Arbitrary symbols (Could you tell the difference between 10000 dots and 9999 dots?) 14 Stages of perceptual processing 1. Parallel processing to extract low-level properties of the visual scene ! rapid parallel processing ! extraction of features, orientation, color, texture, and movement patterns ! iconic store ! bottom-up, data driven processing 2. -

Understanding the Effective Receptive Field in Deep Convolutional Neural Networks

Understanding the Effective Receptive Field in Deep Convolutional Neural Networks Wenjie Luo∗ Yujia Li∗ Raquel Urtasun Richard Zemel Department of Computer Science University of Toronto {wenjie, yujiali, urtasun, zemel}@cs.toronto.edu Abstract We study characteristics of receptive fields of units in deep convolutional networks. The receptive field size is a crucial issue in many visual tasks, as the output must respond to large enough areas in the image to capture information about large objects. We introduce the notion of an effective receptive field, and show that it both has a Gaussian distribution and only occupies a fraction of the full theoretical receptive field. We analyze the effective receptive field in several architecture designs, and the effect of nonlinear activations, dropout, sub-sampling and skip connections on it. This leads to suggestions for ways to address its tendency to be too small. 1 Introduction Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have achieved great success in a wide range of problems in the last few years. In this paper we focus on their application to computer vision: where they are the driving force behind the significant improvement of the state-of-the-art for many tasks recently, including image recognition [10, 8], object detection [17, 2], semantic segmentation [12, 1], image captioning [20], and many more. One of the basic concepts in deep CNNs is the receptive field, or field of view, of a unit in a certain layer in the network. Unlike in fully connected networks, where the value of each unit depends on the entire input to the network, a unit in convolutional networks only depends on a region of the input. -

Do We Know What the Early Visual System Does?

The Journal of Neuroscience, November 16, 2005 • 25(46):10577–10597 • 10577 Mini-Symposium Do We Know What the Early Visual System Does? Matteo Carandini,1 Jonathan B. Demb,2 Valerio Mante,1 David J. Tolhurst,3 Yang Dan,4 Bruno A. Olshausen,6 Jack L. Gallant,5,6 and Nicole C. Rust7 1Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute, San Francisco, California 94115, 2Departments of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, and Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48105, 3Department of Physiology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 1TN, United Kingdom, Departments of 4Molecular and Cellular Biology and 5Psychology and 6Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute and School of Optometry, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, California 94720, and 7Center for Neural Science, New York University, New York, New York 10003 We can claim that we know what the visual system does once we can predict neural responses to arbitrary stimuli, including those seen in nature. In the early visual system, models based on one or more linear receptive fields hold promise to achieve this goal as long as the models include nonlinear mechanisms that control responsiveness, based on stimulus context and history, and take into account the nonlinearity of spike generation. These linear and nonlinear mechanisms might be the only essential determinants of the response, or alternatively, there may be additional fundamental determinants yet to be identified. Research is progressing with the goals of defining a single “standard model” for each stage of the visual pathway and testing the predictive power of these models on the responses to movies of natural scenes. -

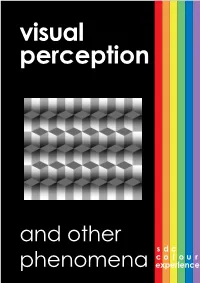

Visual Perception

visual perception and other s d c c o l o u r phenomena experience Visual perception Visual perception is the process of using vision to acquire information about the surrounding environment or situation. Perception relies on an interaction between the eye and the brain and in many cases what we perceive is not, in fact, reality. There are four different ways in which humans visually perceive the world. When we observe an object we recognise: brightness, movement, shape, colour. The illustration on the front cover appears to have two distinctly different sets of horizontal diamonds, one darker than the other. As shown above with an area removed this is an incorrect perception as in reality the diamonds are all identical. Ouchi effect Named after the Japanese artist Hajime Ouchi who discovered that when horizontal and vertical patterns are combined the eye jitters over the image and the brain perceives movement where none exists. Blinking effect Try to count the dots in the diagram above. Despite a static image, your eyes will make it dynamic and attempt to fill in the yellow circles with the blue of the background. The reason behind this is not yet fully understood. When coloured lines cross over neutral background the dots appear to be coloured. If the neutral lines cross the coloured then the dots appear neutral. When the grids are distorted the illusion is reduced or disappears completely as shown in the examples above. Dithering This is a colour reproduction technique in which dots or pixels are arranged in such a way that allows us to perceive more colours than are actually there. -

C:\Vision\17Performance Pt 2.Wpd

PROCESSES IN BIOLOGICAL VISION: including, ELECTROCHEMISTRY OF THE NEURON This material is excerpted from the full β-version of the text. The final printed version will be more concise due to further editing and economical constraints. A Table of Contents and an index are located at the end of this paper. James T. Fulton Vision Concepts [email protected] April 30, 2017 Copyright 2001 James T. Fulton Performance Descriptors, Pt II, 17- 1 17 Performance descriptors of Vision1 PART II: TEMPORAL & SPATIAL PERFORMANCE The press of work on other parts of the manuscript may delay the final cleanup of this PART but it is too valuable to delay its release for comment. [Author] Any comments are welcome. It will eventually include an evaluation of the bandwidth of the luminance and chrominance channels in support of the chapter on the tertiary circuits, Chapter 14, including the work of de Lange Dzn and Stockman, MacLeod & Lebrun in Section 17.6.6.5. 17.5 The Temporal Characteristic of the human eye The overall temporal characteristics of animal vision are difficult to quantify. It is frequently easier to perform experiments in either the transient or the steady state domain. To arrive at a unified mathematical model, it is necessary to analyze both classes of data and make the necessary mathematical manipulations to bring all of the data into a single domain. After a general discussion of background material, the main discussion will be separated into a transient section and a frequency response section in order to show how the model correlates with the data from various earlier investigators.