The Rise of the Dramedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FBI Kilis Hijacker at Portland Airport

Daily Weather Partly cloudy with a chance of foggy brains. Barometric "finals" pressure above normal. Highs, not until next week. Lows, in the gutter. Chance of Teen Soviet satellites falling, 100 percent. Chance of grades falling, 95 percent. Chance of snow falling, unlikely. Pullman, Washington Vol. LXXXIX No. 74 Established 1894 Friday, January 21,1983 FBI ki lis hijacker at Portland airport by Bob Baum freeze. Associated Press Writer ., At that time the suspect made a sudden motion with the box as if to throw it at the agent (who) fired one shot." Baker said. PORTLAND, Ore. (AP - A man claiming to FBI agents here would not identify the hijacker. have a bomb and saying he wanted to go to Afgha- But Dick Paulson. spokesman for the Washington nistan was shot and killed Thursday after he hi- Department of Corrections. said the FBI told him jacked a Northwest Orient jetliner carrying 41 they found identification on the body saying he people from Seattle to Portland, authorities said. was Glenn Kurt Tripp. 20. of Arlington. Wash .. He was identified as a man arrested 21/2years ago who attempted to hijack a Northwest Orient flight for attempting to hijack a jetliner. In July 1980. Paulson said Tripp was on 20 years' "The passengers and crew are safe." said Brent probation for first-degree extortion and first- Baskfield, a Northwest Orient official. degree kidnapping in that incident. FBI agents stormed the Boeing 727-200 about In the earlier hijack attempt. Tripp. then 17. 21/2 hours after the plane landed. shooting the claimed to have a bomb in a briefcase and deman- hijacker once with a .38-caliber revolver as pas- ded $100.000, authorities said at the time. -

Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Home (/gendersarchive1998-2013/) Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock May 1, 2012 • By Linda Mizejewski (/gendersarchive1998-2013/linda-mizejewski) [1] The title of Tina Fey's humorous 2011 memoir, Bossypants, suggests how closely Fey is identified with her Emmy-award winning NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006-), where she is the "boss"—the show's creator, star, head writer, and executive producer. Fey's reputation as a feminist—indeed, as Hollywood's Token Feminist, as some journalists have wryly pointed out—heavily inflects the character she plays, the "bossy" Liz Lemon, whose idealistic feminism is a mainstay of her characterization and of the show's comedy. Fey's comedy has always focused on gender, beginning with her work on Saturday Night Live (SNL) where she became that show's first female head writer in 1999. A year later she moved from behind the scenes to appear in the "Weekend Update" sketches, attracting national attention as a gifted comic with a penchant for zeroing in on women's issues. Fey's connection to feminist politics escalated when she returned to SNL for guest appearances during the presidential campaign of 2008, first in a sketch protesting the sexist media treatment of Hillary Clinton, and more forcefully, in her stunning imitations of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, which launched Fey into national politics and prominence. [2] On 30 Rock, Liz Lemon is the head writer of an NBC comedy much likeSNL, and she is identified as a "third wave feminist" on the pilot episode. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Annual Fund Impact Report 2018–19 Thank You

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO BOOTH SCHOOL OF BUSINESS Annual Fund Impact Report 2018–19 Thank you. Your gift is making it possible for the University of Chicago Booth School of Business to empower bold thinkers and inquisitive minds to dig deeper, discover more, and shape the future. Annual Fund Impact The Chicago Booth Annual Fund had a strong fiscal year 2019 (July 1, 2018–June 30, 2019), with $10,737,935 in unrestricted funding. The Annual Fund also continues to shatter goals for the University of Chicago Campaign: Inquiry and Impact, which will come to a close December 2019. The Annual Fund has raised more than $119.6 million since that campaign began. Your gifts to the Annual Fund made the following possible: • CURRICULAR INNOVATION: Chicago Booth offers a • GLOBAL INITIATIVES: Chicago Booth will relocate its flexible, multidisciplinary approach to the study of current campus in London in late spring 2020. Booth’s business. Booth added 12 new courses for the 2018–19 campus will move to One Bartholomew Close in Barts academic year, including “Diversity in Organizations,” Square, a short walk from St. Paul’s Cathedral and the “Strategic Investment Decisions,” and “Corporate Social Museum of London. This recommitment to the Executive Responsibility Practicum.” Booth’s curriculum exemplifies MBA Program in London will strengthen our impact across the school’s unique and challenging environment and the globe, reflecting an international approach to thinking prepares students for any business challenge at any point about business and finance. in their careers. • SCHOLARSHIPS: One of our key priorities is to attract the • FACULTY RESEARCH: The influential ideas of Booth’s best talent and enroll every student with great promise. -

FALL 2011 HONOR ROLLS by HOMETOWN (In-State Students, Followed by out of State Beginning Page 27)

1 UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL OKLAHOMA FALL 2011 HONOR ROLLS BY HOMETOWN (In-state students, followed by out of state beginning page 27) Ada (President's Honor Roll) Matthew Scott Robinson and Emily L. Robnett Ada (Dean's Honor Roll) Kathlyn J. Babcock; Jeffrey D. Branscum; Haley D. Ray; Lindsey T. Simms; and Dylan Tolbert Walling Adair (Dean's Honor Roll) Teddi L. Meislahn Alex (President's Honor Roll) Carissa J. Zeiset Allen (Dean's Honor Roll) Heather R. Nelson Altus (President's Honor Roll) Trent Bradley Harvick Altus (Dean's Honor Roll) Mariz Escobar; Preston T. Runyan; Nicole Marie Tubbs; and Dallas Owen Wiginton Alva (Dean's Honor Roll) Christopher J. Dowling Antlers (Dean's Honor Roll) Laura Wolfe Apache (Dean's Honor Roll) Kendyl L. Sexton Arcadia (President's Honor Roll) Rebecca L. Irvin Arcadia (Dean's Honor Roll) Hailey Ryan Barry; Stanislav Vyacheslavovivh; Melinda Natasha Kruger; and Caitlyn Lee Tyler Ardmore (President's Honor Roll) Craig Walton McMurry; Karissa D. Rowley; Sarah Luann Smith; and Kaili Brianne Tucker Ardmore (Dean's Honor Roll) Shannon Elaine Barrett; Jacci A. Blankenship; Veronique Clairese Parker; Evan Paul 2 Pearson; and Zachgery Austin Scurry Atoka (Dean's Honor Roll) Lauren A. Mead; Bobby Lee Moore; and Wesley Dewayne Snead Bartlesville (President's Honor Roll) Dylan James Muzljakovich; Alexis N. Quinn; and Amanda Fae Thomas Bartlesville (Dean's Honor Roll) Melissa Kaye Neel; Aaron John Rodgers; Itzel D. Romo; Aaron Alexander Snively; and Katy Ann VanDeVenter Bethany (President's Honor Roll) Shelby C. Allen; Jordan Leigh Crump; Jamie L. Garrett; Sandy Guzman; Rachael Marie Harmon; Laura B. -

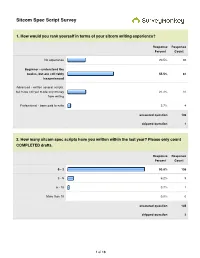

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

Act One Fade In: Int. Studio Backstage

30 ROCK 113: "The Head and The Hair" 1. Shooting Draft Third Revised (Yellow) 12/13/06 ACT ONE FADE IN: 1 INT. STUDIO BACKSTAGE - NIGHT 1 The show is in full swing. We hear a laugh from inside the studio, then applause and the band kicking in. The double doors burst open and JENNA, dressed as a fat old lady, LIZ, and a QUICK-CHANGE DRESSER enter the backstage chaos from the studio. In the background we see the STAGE MANAGER. STAGE MANAGER We’re back in two minutes! The dresser starts going to work on Jenna; tearing off a wig, casting aside props and jewelry. PETE is there. JENNA (to Liz) So are you gonna ask out the Head? Liz rolls her eyes. PETE The “Head”? LIZ There are these two MSNBC guys we keep seeing around. They just moved offices from New Jersey. We don’t know their names so we call them the Head and the Hair. PETE How come? FLASH BACK TO: 2 INT. ELEVATOR/ELEVATOR BANK - EARLIER THAT DAY 2 Liz and Jenna are on the elevator coming in to work. Two guys get on. One guy is super handsome and has great hair. This is THE HAIR, GRAY. The other guy is cranial and nerdy looking. This is THE HEAD. Liz smiles politely. Jenna gives the Hair a huge grin. GRAY Hey! You guys again. Jenna laughs too hard at this non-joke. 30 ROCK 113: "The Head and The Hair" 2. Shooting Draft Third Revised (Yellow) 12/13/06 JENNA How are things going? Are you settling in okay? GRAY We’re finding our way around. -

Deborah Barylski

DEBORAH BARYLSKI CASTING DIRECTOR (310) 314-9116 (h) SELECTED CREDITS (310) 795-2035 (c) FEATURE FILMS [email protected] PASTIME* Prod: Robin Armstrong, Eric Young Dir: R. Armstrong *Winner, Audience Award, Sundance MOVIES FOR TELEVISION ALLEY CATS STRIKE (Disney Cannel) Execs: Carol Ames, Don Safran, Michael Cieply Dir: Rod Daniel A PLACE TO BE LOVED (CBS) Exec. Producer: Beth Polson Dir: Sandy Smolan A MESSAGE FROM HOLLY (CBS) Exec. Producer: Beth Polson Dir: Rod Holcomb BACK TO THE STREETS OF SF (NBC) Exec. Producer: Diana Kerew, M. Goldsmith Dir: Mel Damski GUESS WHO'S COMING FOR XMAS? Exec. Producer: Beth Polson Dir: Paul Schneider TELEVISION: PILOT & SERIES *Winner, EMMY and Artios Awards for Casting for a Comedy Series, 2004 **Artios Award nomination SAINT GEORGE Execs: M.Williams,D. McFadzean,G.Lopez,M.Rotenberg Lionsgate/FX BACK OF THE CLASS Execs: Hugh Fink, Porter, Dionne, Weiner Nickelodeon DIRTY WORK (Won New Media Emmy) Execs: Zach Schiff-Abrams, Jackie Turnure, A. Shure Fourth Wall Studios THE MIDDLE Execs: Eileen Heisler, DeAnn Heline Warners/ABC UNTITLED DANA GOULD PROJECT Execs: D. Gould, Mike Scully, T. Lassally, D. Becky Warners/ABC THE EMANCIPATION OF ERNESTO Execs: Emily Kapnek, Wilmer Valderama 20th/Fox STARTING UNDER Exec. Bruce Helford/Mohawk Warners/Fox HACKETT Execs: Sonnenfeld, Moss, Timberman, Carlson Sony/FBC NICE GIRLS DON’T GET THE CORNER OFFICE. Execs: Nevins, Sternin, Ventimilia Imagine & 20th/ABC THE WAR AT HOME Exec. Rob Lotterstein, M.Schultheis, M.Hanel 20th/Warners/Fox KITCHEN CONFIDENTIAL Execs: D. Star, D. Hemingson, & New Line Fox/FBC THE ROBINSON BROTHERS Exec. Mark O’Keefe, Adelstein, Moritz,Parouse 20th/ORIGINAL/FBC ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT* Exec. -

Hope Made Possible by You

Hope Made Possible by You 2014 Annual Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Trustees .....................................................................................4 Jamie Hodge - 2014 Board Chair ............................................................5 Brenda James - 2013 Board Chair ...........................................................6 Beatrice Kelly - Employee Champion .......................................................7 Charlie & Judy Bradshaw - Community Partners ......................................8 Dr. Julian Josey - Visionary for the Future ..............................................10 Special Initiatives ...................................................................................12 Cancer Division Focus ............................................................................13 Heart Division Focus ..............................................................................14 Hospice Division Focus ..........................................................................15 Foundation Financials ............................................................................16 Grant Awards .........................................................................................18 Donor Listings ........................................................................................20 Spartanburg Regional Healthcare System Accolades .............................52 2 Hope Made Possible By You Thank you for being our partner! With your help, we are making a measurable difference in health and wellness -

· Burt Shevelove Larry Gelbart Stephen Sondheim Rosemary Gass

From the Book by · Burt Shevelove Larry Gelbart Music and Lyrics Stephen Sondheim Director Rosemary Gass Musical Direction Tyler Driskill Choreography Kat Walsh Ann Arbor Civic Theatre Board of Directors Advisory Board Darrell W. Pierce - President Anne Bauman - Chair Paul Bianchi -Vice President Robin Barlow Fred Patterson - Treasurer JohnEman Linda Borgsdorf- Secretary Robert Green Linda Carriere David Keren Paul Cumming Ron Miller Caitlin Frankel Rowe Deanna Relyea Douglas Harris Judy Dow Rumelhart Thorn Johnson Ingrid Sheldon Nathaniel Madura Gayle Steiner Lindsay McCarthy Keith Taylor Teresa Myers Sheryl Yengera Matthew Rogers Ann Arbor Civic Theatre is proud to honor Helen Mann Andrews, Burnette Staebler, and Phyllis Wright for their years of service on the Advisory Board. Suzi Peterson Emily Rogers Cassie Mann Managing Director Volunteer Coordinator Program Director 322 WEST ANN STREET ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48104 box office (734) 971-2228 office (734) 971-0605 WWW.A2CT.ORG Ann Arbor Civic Theatre Opening night June 5, 2008 Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre Book by Burt Shevelove and Larry Gelbart Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Directed by Rosemary Gass Music Direction by Choreographed by Tyler Driskill Kat Walsh Assistant Director Producer Stage Manager Kat Walsh Douglas Harris Cathy Cassar Technical Set Designer Lighting Designer Artistic Set Designer Cathy Cassar Tiff Crutchfield Katie Cook Wilcox Hair and Makeup Properties and Set Dressing Costume Designer Susie Berneis Tina Mayer Susie Berneis Graphic Designer Costume Assistant House Manager Katie Cook Wilcox Alexandra Berneis Kyle Newmeyer Publicity Photographer Tom Steppe Produced through special arrangement with Music Theatre International 421 West 54th Street, New York, NY 10019 www.mtishows.com From the Director The director's note.. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process.