Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conceptual Plan

About the Cover Photo The photo on the cover of this report was taken on December 17, 2010, around 8:00 AM. The view is from the Savin Hill Avenue overpass and looks almost directly south. This overpass is shown in Figure 3-3 of the report, and the field of view includes land shown in Figure 3-2. At the right is the recently completed headhouse of the Savin Hill Red Line station. Stopped at the station platform is an inbound Red Line train that started at Ashmont and will travel to Alewife. The station is fully ADA-compliant, and the plan presented in this report requires no modification to this station. Next to the Red Line train is an inbound train from one of the three Old Colony commuter rail branches. There is only one track at this location, as is the case throughout most of the Old Colony system. This train has a mixed consist of single-level and bi-level coaches, and is being pushed by a diesel locomotive, which is mostly hidden from view by the bi-level coaches. Between the two trains is an underpass beneath the Ashmont branch of the Red Line. This had been a freight spur serving an industrial area on the west side of the Ashmont branch tracks. Sections A-2.3 and A-2.4 of this report present an approach to staging railroad reconstruction that utilizes the abandoned freight spur and underpass. The two tracks to the left of the Old Colony tracks serve the Braintree Red Line branch. -

The Hub's Metropolis: a Glimpse Into Greater Boston's Development

James C. O’Connell, “The Hub’s Metropolis: Greater Boston’s Development” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 42, No. 1 (Winter 2014). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.wsc.ma.edu/mhj. 26 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2014 Published by The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 7x9 hardcover, 326 pp., $34.95. To order visit http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/hubs-metropolis 27 EDITor’s choicE The Hub’s Metropolis: A Glimpse into Greater Boston’s Development JAMES C. O’CONNELL Editor’s Introduction: Our Editor’s Choice selection for this issue is excerpted from the book, The Hub’s Metropolis: Greater Boston’s Development from Railroad Suburbs to Smart Growth (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2013). All who live in Massachusetts are familiar with the compact city of Boston, yet the history of the larger, sprawling metropolitan area has rarely been approached as a comprehensive whole. As one reviewer writes, “Comprehensive and readable, James O’Connell’s account takes care to orient the reader in what is often a disorienting landscape.” Another describes the book as a “riveting history of one of the nation’s most livable places—and a roadmap for how to keep it that way.” James O’Connell, the author, is intimately familiar with his topic through his work as a planner at the National Park Service, Northeast Region, in Boston. -

Interstate 93 Web052305

INTERSTATE 93: A MODEST PROPOSAL by J. Mark Lennon Interstate 93 needs to be widened. Soon. Now. It is tough to believe that thousands of commuters – or anyone else – will get out of their cars to take a train. It is tough to believe, even with high-and-getting-higher gas prices, that thousands of commuters will carpool. It is tough to believe that hundreds of companies will institute flex time to spread out the morning and evening commute. Or that thousands of commuters would take advantage of the flexibility if they had it. It is tough to believe that weekend skiers or hikers or boaters or snowmobilers will do something other than herd north en masse on Friday nights, and herd back south Sundays. Interstate 93 needs to be widened. But eight lanes, at a cost of $440 million and up to ten years of construction, are a dumb idea. Eight lanes will turn New Hampshire’s tree-lined threshold into a bleak, Jerseyesque eyesore. Take a drive through Secaucus for a glimpse of this future. Four hundred forty million dollars will consume, for a decade or more, practically every bit of highway money in the state. Dozens of other projects, equally needed to accommodate growth and enhance safety, will be pushed aside. Most disturbing, a widened I-93 will bring rapid growth to 50 or 60 communities in southern and central New Hampshire, but the $440 million price tag will preclude or delay dozens of local highway improvements needed to accommodate the growth. The result, once you leave the interstate, will be more congestion, more delays, and less safety. -

Route 128 / Interstate 95 Woburn, Massachusetts

LOCATION More than 550 feet of unprecedented frontage on Route 128/I-95. Superb access to Route 128 / I-95, I-93, Massachusetts Turnpike (I-90), Route 3, Route 2, and Route 1. Route 128 / I-95 access via both Exits 34 and 35. Route 128 / Interstate 95 11 miles to downtown Boston and Woburn, Massachusetts Logan International Airport. Minutes from Interstate 93 and Anderson Cummings Properties announces the Regional Transportation Center–home development of TradeCenter 128 – to Logan International Airport Shuttle 400,000 SF of unprecedented first-class and MBTA Commuter Rail. space fronting Route 128 / I-95 in Woburn, minutes from I-93. With nearly 40 years experience in commercial real estate, developer Cummings Properties has earned a long-standing reputation for operations and service excellence. Cummings Properties has designed and built hundreds of specialized facilities including, cleanrooms, biotech labs, and operating rooms, as 781-935-8000 cummings.com well as thousands of office, retail, warehouse, and R&D spaces. 400,000 Square Feet • 7 Stories • Covered Parking • Abutting Route 128 / I-95 This flagship property offers the finest quality corporate lifestyle with the amenities of a central business district. It is the largest single building ever developed by Cummings Properties and will receive the best of our nearly 40 years of experience. A 3-story drive-through gateway welcomes patrons to TradeCenter 128. DESIGN Energy efficient design and construction means Up to 63,000 SF per floor. Wide-open floor reduced operating costs, healthier and more plans provide maximum flexibility in layout. productive occupants, and conservation of natural resources. -

Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All Hazardous Cargo (HC) and Cargo Tankers General Information Throughout Boston and Surrounding Towns

WELCOME TO MASSACHUSETTS! CONTACT INFORMATION REGIONAL TOURISM COUNCILS STATE ROAD LAWS NONRESIDENT PRIVILEGES Massachusetts grants the same privileges EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE Fire, Police, Ambulance: 911 16 to nonresidents as to Massachusetts residents. On behalf of the Commonwealth, MBTA PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 2 welcome to Massachusetts. In our MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 10 SPEED LAW Observe posted speed limits. The runs daily service on buses, trains, trolleys and ferries 14 3 great state, you can enjoy the rolling Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All hazardous cargo (HC) and cargo tankers General Information throughout Boston and surrounding towns. Stations can be identified 13 hills of the west and in under three by a black on a white, circular sign. Pay your fare with a 9 1 are prohibited from the Boston Tunnels. hours travel east to visit our pristine MassDOT Headquarters 857-368-4636 11 reusable, rechargeable CharlieCard (plastic) or CharlieTicket 12 DRUNK DRIVING LAWS Massachusetts enforces these laws rigorously. beaches. You will find a state full (toll free) 877-623-6846 (paper) that can be purchased at over 500 fare-vending machines 1. Greater Boston 9. MetroWest 4 MOBILE ELECTRONIC DEVICE LAWS Operators cannot use any of history and rich in diversity that (TTY) 857-368-0655 located at all subway stations and Logan airport terminals. At street- 2. North of Boston 10. Johnny Appleseed Trail 5 3. Greater Merrimack Valley 11. Central Massachusetts mobile electronic device to write, send, or read an electronic opens its doors to millions of visitors www.mass.gov/massdot level stations and local bus stops you pay on board. -

Boston-Montreal High Speed Rail Project

Boston to Montreal High- Speed Rail Planning and Feasibility Study Phase I Final Report prepared for Vermont Agency of Transportation New Hampshire Department of Transportation Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Construction prepared by Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas with Cambridge Systematics Fitzgerald and Halliday HNTB, Inc. KKO and Associates April 2003 final report Boston to Montreal High-Speed Rail Planning and Feasibility Study Phase I prepared for Vermont Agency of Transportation New Hampshire Department of Transportation Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Construction prepared by Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Fitzgerald and Halliday HNTB, Inc. KKO and Associates April 2003 Boston to Montreal High-Speed Rail Feasibility Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... ES-1 E.1 Background and Purpose of the Study ............................................................... ES-1 E.2 Study Overview...................................................................................................... ES-1 E.3 Ridership Analysis................................................................................................. ES-8 E.4 Government and Policy Issues............................................................................. ES-12 E.5 Conclusion.............................................................................................................. -

Appendix E Detailed Case Studies

Guidelines for Providing Access to Public Transportation Stations APPENDIX E DETAILED CASE STUDIES Revised Final Report 2011 Page E-1 Detailed Case Studies Guidelines for Providing Access to Public Transportation Stations TABLE OF CONTENTS Case Study Summary ............................................................................................................................... E-3 Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) .............................................................................................................. E-7 Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) ........................................... E-21 Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) ................................................................ E-33 Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) ..................................................................... E-41 Metro-North Railroad ............................................................................................................................. E-57 New Jersey Transit (NJT) ....................................................................................................................... E-67 OC Transpo .............................................................................................................................................. E-81 Regional Transit District Denver (RTD) ............................................................................................... E-93 Sound Transit ........................................................................................................................................ -

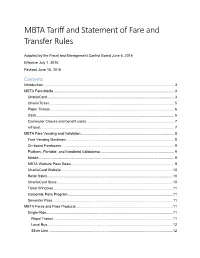

MBTA Tariff and Statement of Fare and Transfer Rules

MBTA Tariff and Statement of Fare and Transfer Rules Adopted by the Fiscal and Management Control Board June 6, 2016 Effective July 1, 2016 Revised June 15, 2018 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 MBTA Fare Media ...................................................................................................................... 3 CharlieCard ............................................................................................................................ 3 CharlieTicket .......................................................................................................................... 5 Paper Tickets ......................................................................................................................... 6 Cash ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Commuter Checks and benefit cards ...................................................................................... 7 mTicket ................................................................................................................................... 7 MBTA Fare Vending and Validation ........................................................................................... 8 Fare Vending Machines .......................................................................................................... 8 On-board Fareboxes ............................................................................................................. -

December 11, 2007

COORDINATED PUBLIC TRANSIT- HUMAN SERVICES TRANSPORTATION PLAN December 11, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Goal 1: Assess Current Transportation Resources 5 Goal 2: Identify Gaps in Service 16 Goal 3: Identify Strategies for Addressing Service Gaps 20 And Prioritize Criteria for Evaluation 22 Comments 24 Signatory Page 26 2 Merrimack Valley Planning Commission INTRODUCTION In August 2005, the U.S. Congress passed the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient, Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU) reauthorizing the Surface Transportation Act. SAFTEA-LU established the requirement that Metropolitan Planning Organizations must develop the Coordinated Public Transit-Human Services Transportation Plan as a prerequisite for receiving Federal Transit Administration (FTA) funding under the Special Needs of Elderly Individuals, Job Access and Reverse Commute (JARC) and New Freedom programs and Specialized Transportation funds. The intent of this provision is to improve the quality of transportation for the elderly, disabled persons, welfare recipients, low-income persons and people doing reverse commutes by assessing their transportation needs, minimizing the duplication of services and achieving cost efficiencies. In order for a project to be funded through the New Freedom or JARC programs, it must be included in the Coordinated Public Transit-Human Services Transportation Plan. Coordination is required during all stages, including planning, implementation and for the duration of the project. In April 2007, the Merrimack Valley Planning Commission received direction from the Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Public Works (EOTPW) to draft the Coordinated Public Transit-Human Services Transportation Plan. EOTPW will administer the funds for all three funding programs, but through this public participation process, is working with the regional planning commissions, such as MVPC, to seek public input into the gaps and needs in service in our region. -

![[Docket No. FD 36472] CSX Corporation And](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1964/docket-no-fd-36472-csx-corporation-and-1991964.webp)

[Docket No. FD 36472] CSX Corporation And

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 07/30/2021 and available online at FR-4915-01-P federalregister.gov/d/2021-16328, and on govinfo.gov SURFACE TRANSPORTATION BOARD [Docket No. FD 36472] CSX Corporation and CSX Transportation, Inc., et al.—Control and Merger— Pan Am Systems, Inc., Pan Am Railways, Inc., Boston and Maine Corporation, Maine Central Railroad Company, Northern Railroad, Pan Am Southern LLC, Portland Terminal Company, Springfield Terminal Railway Company, Stony Brook Railroad Company, and Vermont & Massachusetts Railroad Company AGENCY: Surface Transportation Board. ACTION: Decision No. 4 in STB Finance Docket No. 36472; Notice of Acceptance of Application and Related Filings; Issuance of Procedural Schedule. SUMMARY: The Surface Transportation Board (Board) is accepting for consideration the revised application filed on July 1, 2021, by CSX Corporation (CSXC), CSX Transportation Inc. (CSXT), 747 Merger Sub 2, Inc. (747 Merger Sub 2), Pan Am Systems, Inc. (Systems), Pan Am Railways, Inc. (PAR), Boston and Maine Corporation (Boston & Maine), Maine Central Railroad Company (Maine Central), Northern Railroad (Northern), Portland Terminal Company (Portland Terminal), Springfield Terminal Railway Company (Springfield Terminal), Stony Brook Railroad Company (Stony Brook), and Vermont & Massachusetts Railroad Company (V&M) (collectively, Applicants). The application will be referred to as the Revised Application. The Revised Application seeks Board approval under 49 U.S.C. 11321-26 for: CSXC, CSXT, and 747 Merger Sub 2 to control the seven railroads controlled by Systems and PAR, and CSXT to merge six of the seven railroads into CSXT. This proposal is referred to as the Merger Transaction. -

Annual Report of the Directors of the Boston and Maine Railroad for the Year Ending

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY 585A B665 I873/T5 I 887'/86 REPORT OF THE DIRECTORS Boston & Maine Railroad TO THE STOCKHOLDERS. §7§7€3ClI3£BE5Ci£%§7" IIDEBCZ. 1!), lE?7T3. BOSTON: ALFRED MUDGE & SON, PRINTERS, 34 SCHOOL STREET. 1873. BOARD OF DIRECTORS. NATHANIEL G. WHITE, LAWRENCE. E. J. M. HALE, HAVERHILL. GEORGE C. LORD, BOSTON. AMOS PAUIJ, S0. NEWMARKET, N. H. JOHN E. BICKFORD, Dovza, N. H. *CYRUS WAKEFIELD, WAKEFIELD. NATHANIEL J. BRADLEE, BOSTON. * Deceased. Cu: 221+ B665 ma 1'1/vs-‘Ian/sq, l$<5°>l754 wa. r»i\r-:7 ANNUAL REPORT. To the Slocklzolders of the Boston and Maine Railroad . THE Directors respectfully submit the following report, exhibiting the result of the operations of the road for the year ending September 30th, 1873 : - The gross receipts of the year ending Sep tember 30th, 1873, were $2,300,093 68 The operating expenses were 1,727,825 00 Net earnings for the year . $572,268 68 Being a little more than eight percent upon the whole capital authorized. The gross earnings of the twelve months ending September 30, 1872, were $2,046,142 19 And the expenses for the same time were 1,542,026 00 Showing ‘an increase in the receipts of the present year over the previous year of 253,951 49 And in the expenses of 185,799 00 The net income for the year ending Septem ber 30, 1872, was 504,116 19 Showing an increase in the net income of thepresent year over the previous year of 68,152 49 The expenses of the past year have been large; this results in part from the severity of the last winter, which for the transaction of railroad business was the most severe known for years, and put to the severest test all our rolling stock, increasing greatly our expenses. -

Meeting Summary

I-93 Transit Investment Study Technical Advisory Committee Meeting Tuesday, September 19, 2006 10:00 AM Nashua Regional Planning Commission Attendance People who signed in: Andrew Motter Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Region 1 Steve Williams Nashua Regional Planning Commission (NRPC) Lynn Ahlgren Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation (EOT) Stephen Woelfel EOT – Transit Planning Cliff Sinnott Rockingham Planning Commission Chris Curry Northern Middlesex Council of Governments (NMCOG) Paul Hajec NMCOG Tom Irwin Conservation Law Foundation Bill O’Donnell Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) – New Hampshire Kit Morgan New Hampshire Department of Transportation (NHDOT) Ram Maddali NHDOT Matt Caron Southern New Hampshire Planning Commission (SNHPC) Tim White SNHPC Bill Cass NHDOT Jim Gallagher Metropolitan Area Planning Commission Consultant Staff: Ken Kinney HNTB Corporation Marcy Miller Fitzgerald & Halliday, Inc. Ken Livingston Fitzgerald & Halliday, Inc. Dennis Coffey HNTB Corporation Joe Castiglione Parsons Brinckerhoff (PB) John Weston PB David Nelson Edwards & Kelsey (E& K) Yawa Duse-Anthony E& K Essek Petrie HNTB Welcome and Introduction of Consultant Ken Kinney welcomed everyone and asked that each individual introduce him or herself. He proceeded to review the agenda for the meeting and the proposed final products of the study. He asked the project team members to provide brief overviews of progress on initial study tasks. Initial Study Tasks Essek Petrie, of HNTB, gave an overview of the review of existing condition reports and studies. HNTB is in the process of collecting and synthesizing the reports and has a good start on the population and employment data for the region. He presented the bibliography that lists and provides links to many of these existing reports.