PSAD-77-74 Nuclear Or Conventional Power for Surface Combatant Ships?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes

US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes BRAD ELWARD ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com NEW VANGUARD 211 US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes BRAD ELWARD ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 ORIGINS OF THE CARRIER AND THE SUPERCARRIER 5 t World War II Carriers t Post-World War II Carrier Developments t United States (CVA-58) THE FORRESTAL CLASS 11 FORRESTAL AS BUILT 14 t Carrier Structures t The Flight Deck and Hangar Bay t Launch and Recovery Operations t Stores t Defensive Systems t Electronic Systems and Radar t Propulsion THE FORRESTAL CARRIERS 20 t USS Forrestal (CVA-59) t USS Saratoga (CVA-60) t USS Ranger (CVA-61) t USS Independence (CVA-62) THE KITTY HAWK CLASS 26 t Major Differences from the Forrestal Class t Defensive Armament t Dimensions and Displacement t Propulsion t Electronics and Radars t USS America, CVA-66 – Improved Kitty Hawk t USS John F. Kennedy, CVA-67 – A Singular Class THE KITTY HAWK AND JOHN F. KENNEDY CARRIERS 34 t USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) t USS Constellation (CVA-64) t USS America (CVA-66) t USS John F. Kennedy (CVA-67) THE ENTERPRISE CLASS 40 t Propulsion t Stores t Flight Deck and Island t Defensive Armament t USS Enterprise (CVAN-65) BIBLIOGRAPHY 47 INDEX 48 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS FORRESTAL, KITTY HAWK AND ENTERPRISE CLASSES INTRODUCTION The Forrestal-class aircraft carriers were the world’s first true supercarriers and served in the United States Navy for the majority of America’s Cold War with the Soviet Union. -

Navy DD(X), CG(X), and LCS Ship Acquisition Programs: Oversight Issues and Options for Congress

Order Code RL32109 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Navy DD(X), CG(X), and LCS Ship Acquisition Programs: Oversight Issues and Options for Congress Updated April 21, 2005 Ronald O’Rourke Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Navy DD(X), CG(X), and LCS Ship Acquisition Programs: Oversight Issues and Options for Congress Summary The Navy in FY2006 and future years wants to procure three new classes of surface combatants — a destroyer called the DD(X), a cruiser called the CG(X), and a smaller surface combatant called the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS). Congress in FY2005 funded the procurement of the first LCS and provided advance procurement funding for the first DD(X), which the Navy wants to procure in FY2007. The FY2006-FY2011 Future Years Defense Plan (FYDP) reduces planned DD(X) procurement to one per year in FY2007-FY2011 and accelerates procurement of the first CG(X) to FY2011. The FY2006 budget requests $666 million in advanced procurement funding for the first DD(X), which is planned for procurement in FY2007, $50 million in advance procurement funding for the second DD(X), which is planned for procurement in FY2008, and $1,115 million for DD(X)/CG(X) research and development. The budget requests $613.3 million for the LCS program, including $240.5 million in research and development funding to build the second LCS, $336.0 million in additional research and development funding, and $36.8 million in procurement funding for LCS mission modules. -

Why Has the Cost of Navy Ships Risen?

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Why Has the Cost of Navy Ships Risen? A Macroscopic Examination of the Trends in U.S. Naval Ship Costs Over the Past Several Decades Mark V. Arena • Irv Blickstein Obaid Younossi • Clifford A. Grammich Prepared for the United States Navy Approved for public release; distribution unlimited The research described in this report was prepared for the United States Navy. -

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress September 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32665 Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the annual rate of Navy ship procurement, the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans, and the capacity of the U.S. shipbuilding industry to execute the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years. In December 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship goal was made U.S. policy by Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115- 91 of December 12, 2017). The Navy and the Department of Defense (DOD) have been working since 2019 to develop a successor for the 355-ship force-level goal. The new goal is expected to introduce a new, more distributed fleet architecture featuring a smaller proportion of larger ships, a larger proportion of smaller ships, and a new third tier of large unmanned vehicles (UVs). On June 17, 2021, the Navy released a long-range Navy shipbuilding document that presents the Biden Administration’s emerging successor to the 355-ship force-level goal. The document calls for a Navy with a more distributed fleet architecture, including 321 to 372 manned ships and 77 to 140 large UVs. A September 2021 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimates that the fleet envisioned in the document would cost an average of between $25.3 billion and $32.7 billion per year in constant FY2021 dollars to procure. -

BUCCANEER BATTALION Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps Unit UNIVERSITY of SOUTH FLORIDA 4202 E

BUCCANEER BATTALION Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps Unit UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA 4202 E. FOWLER AVENUE TAMPA, FL 33620-8480 30 May 2018 SUBJ: BATTALION KNOWLEDGE PACKET 1. Purpose. To establish a set of knowledge that Midshipman will be accounted for during inspection. 2. Background. In the coming weeks a series of personnel inspections and a written military knowledge test are scheduled. The following is a list of potential knowledge topics that Battalion members should familiarize themselves with them. Inspectors are at liberty to ask any questions, but this should be used as a basic guide to inspection preparation. 3. Chain of Command: The President of the United States The Honorable Donald J. Trump The Secretary of Defense The Honorable James Mattis The Secretary of the Navy The Honorable Richard V. Spencer Chief of Naval Operations ADM John M. Richardson, USN Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen Robert B. Neller, USMC Commander, Naval Education and Training Command RADM Kyle J. Cozad, USN Commanding Officer, NROTCU USF CAPT John R. Schmidt, USN Commanding Officer, Battalion MIDN 1/C Alexander Walker 4. Orders to the Sentry: 1. Take charge of this post and all government property in view. 2. Walk my post in a military manner, keep always on the alert and reporting everything that takes place within site or hearing. 3. Report all violations of orders I am instructed to enforce. 4. Repeat all calls from post more distant from the guardhouse (quarter-deck) than my own. 5. Quit my post only when properly relieved. 6. Receive, obey, and pass on the sentry who relieves me, all orders from the Commanding Officer, Command Duty Officer, Officer of the Day, Officer of the Deck, and Officers and Petty Officers of the watch only. -

CGN 9 Long Beach - 1983

CGN 9 Long Beach - 1983 United States Type: CGN - Nuclear Powered Guided Missile Cruiser Max Speed: 31 kt Commissioned: 1983 Length: 219.8 m Beam: 22.3 m Draft: 9.3 m Crew: 825 Displacement: 15525 t Displacement Full: 17500 t Propulsion: 2x C1W Nuclear Reactors Sensors / EW: - AN/SPG-35 [Mk56 GFCS] - Radar, Radar, FCR, Surface-to-Air & Surface-to-Surface, Short-Range, Max range: 25.9 km - AN/SQQ-23B PAIR - (Single-Dome) Hull Sonar, Active/Passive, Hull Sonar, Active/Passive Search & Attack, Max range: 37 km - AN/SPS-48C - (1978) Radar, Radar, Air Search, 3D Long-Range, Max range: 407.4 km - AN/SPG-55B [Mk76 Mod 9 FCS] - (1978) Radar, Radar, FCR, Surface-to-Air, Medium-Range, Max range: 277.8 km - LN-66LP - (AN/SPS-59, 10kW) Radar, Radar, Surface Search, Short-Range, Max range: 59.3 km - AN/SLQ-32(V)3 [ECM] - (Group, 1983) ECM, OECM & DECM, Offensive & Defensive ECM, Max range: 0 km - AN/SLQ-32(V)3 [ESM] - (Group, 1983) ESM, ELINT, Max range: 926 km - AN/SPS-67(V)1 - (1982) Radar, Radar, Surface Search & Navigation, Max range: 64.8 km - AN/SPS-49(V)2 - (1982) Radar, Radar, Air Search, 2D Long-Range, Max range: 463 km Weapons / Loadouts: - Generic GMTR [Guided Missile Training Round] - (Aka Drill Round) Training Round. - RIM-67B SM-2ER Blk I - (1981, No Datalink) Guided Weapon. Air Max: 148.2 km. Surface Max: 46.3 km. - 127mm/38 HE-PD [HiCap] - (USN) Gun. Air Max: 2.8 km. Surface Max: 16.7 km. Land Max: 16.7 km. -

The Cost of the Navy's New Frigate

OCTOBER 2020 The Cost of the Navy’s New Frigate On April 30, 2020, the Navy awarded Fincantieri Several factors support the Navy’s estimate: Marinette Marine a contract to build the Navy’s new sur- face combatant, a guided missile frigate long designated • The FFG(X) is based on a design that has been in as FFG(X).1 The contract guarantees that Fincantieri will production for many years. build the lead ship (the first ship designed for a class) and gives the Navy options to build as many as nine addi- • Little if any new technology is being developed for it. tional ships. In this report, the Congressional Budget Office examines the potential costs if the Navy exercises • The contractor is an experienced builder of small all of those options. surface combatants. • CBO estimates the cost of the 10 FFG(X) ships • An independent estimate within the Department of would be $12.3 billion in 2020 (inflation-adjusted) Defense (DoD) was lower than the Navy’s estimate. dollars, about $1.2 billion per ship, on the basis of its own weight-based cost model. That amount is Other factors suggest the Navy’s estimate is too low: 40 percent more than the Navy’s estimate. • The costs of all surface combatants since 1970, as • The Navy estimates that the 10 ships would measured per thousand tons, were higher. cost $8.7 billion in 2020 dollars, an average of $870 million per ship. • Historically the Navy has almost always underestimated the cost of the lead ship, and a more • If the Navy’s estimate turns out to be accurate, expensive lead ship generally results in higher costs the FFG(X) would be the least expensive surface for the follow-on ships. -

BUCCANEER BATTALION Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps Unit UNIVERSITY of SOUTH FLORIDA 4202 E. FOWLER AVENUE TAMPA, FL 33620-8480

BUCCANEER BATTALION Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps Unit UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA 4202 E. FOWLER AVENUE TAMPA, FL 33620-8480 10 APR 2016 SUBJ: BATTALION KNOWLEDGE PACKET 1. Purpose. To establish a set of knowledge that Midshipman will be accounted for during inspection. 2. Background. In the coming weeks a series of personnel inspections and a written military knowledge test are scheduled. The following is a list of potential knowledge topics that Battalion members should familiarize themselves with them. Inspectors are at liberty to ask any questions, but this should be used as a basic guide to inspection preparation. 3. Chain of Command: The President of the United States The Honorable Barack H. Obama The Secretary of Defense The Honorable Ash Carter The Secretary of the Navy The Honorable Raymond E. Mabus Chief of Naval Operations ADM Jonathan Greenert, USN Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen Robert Neller, USMC Commander, Naval Education and Training Command RADM Donald Quinn, USN Commanding Officer, NROTCU USF CAPT William Ipock, USN Commanding Officer, Battalion MIDN Alex Vrountas, USMC 4. Orders to the Sentry: 1. Take charge of this post and all government property in view. 2. Walk my post in a military manner, keep always on the alert and reporting everything that takes place within site or hearing. 3. Report all violations of orders I am instructed to enforce. 4. Repeat all calls from post more distant from the guardhouse (quarter-deck) than my own. 5. Quit my post only when properly relieved. 6. Receive, obey, and pass on the sentry who relieves me, all orders from the Commanding Officer, Command Duty Officer, Officer of the Day, Officer of the Deck, and Officers and Petty Officers of the watch only. -

Navy Nuclear-Powered Surface Ships: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress

Navy Nuclear-Powered Surface Ships: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in Naval Affairs September 29, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33946 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Navy Nuclear-Powered Surface Ships: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress Summary All of the Navy’s aircraft carriers, but none of its other surface ships, are nuclear-powered. Some Members of Congress, particularly on the House Armed Services Committee, have expressed interest in expanding the use of nuclear power to a wider array of Navy surface ships, starting with the CG(X), a planned new cruiser that the Navy had wanted to start procuring around FY2017. Section 1012 of the FY2008 Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4986/P.L. 110-181 of January 28, 2008) makes it U.S. policy to construct the major combatant ships of the Navy, including ships like the CG(X), with integrated nuclear power systems, unless the Secretary of Defense submits a notification to Congress that the inclusion of an integrated nuclear power system in a given class of ship is not in the national interest. The Navy studied nuclear power as a design option for the CG(X), but did not announce whether it would prefer to build the CG(X) as a nuclear-powered ship. The Navy’s FY2011 budget proposes canceling the CG(X) program and instead building an improved version of the conventionally powered Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class Aegis destroyer. The cancellation of the CG(X) program would appear to leave no near-term shipbuilding program opportunities for expanding the application of nuclear power to Navy surface ships other than aircraft carriers. -

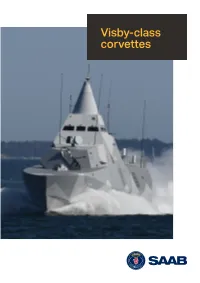

Visby-Class Corvettes VISBY-CLASS CORVETTES

Visby-class corvettes VISBY-CLASS CORVETTES Visby-class corvettes Virtually invisible in all signature bands, the innovative and powerful Visby-class corvettes from Saab continues to set the world benchmark for littoral fighting ships. Stealth, shallow draught, speed and fighting power makes Visby-class corvette a truly formidable surface combatant in the littoral arena. Visby-class corvette is a flexible surface combatant, designed for a wide range of roles: anti-surface warfare (ASuW), anti-submarine warfare (ASW), mine countermeasures (MCM), patrol and much more. Gone are the days when the mere firepower of a ship was sufficient for its own protection. The concept today is action before – or even without – being detected. All-carbon fibre The all-composite carbon-fibre sandwich hull and superstructure allows the 650-ton Visby- class corvette the same payload capacity as that of a steel ship. At the same the carbon-fibre Visby-class corvette’s all-composite carbon- means that the Visby-class corvette has at least fibre hull and superstructure is not only lighter a 50% reduction in displacement compared with than steel, but also comparable for fire resistance a steel ship. and ballistic properties, and superior to steel for Resulting combat advantages are: higher speed vulnerability to blast and underwater explosions. for the same power as conventional metal ship of In terms of life cycle costs, the carbon-fibre com- the same dimensions, as well as greater manoeu- posite is entirely superior to steel and aluminium vrability and shallower draught – both important for fatigue. And the superior corrosion resistance tactical considerations in littoral waters. -

Gao-18-523, Aircraft Carrier Dismantlement and Disposal

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees August 2018 AIRCRAFT CARRIER DISMANTLEMENT AND DISPOSAL Options Warrant Additional Oversight and Raise Regulatory Questions GAO-18-523 August 2018 AIRCRAFT CARRIER DISMANTLEMENT AND DISPOSAL Options Warrant Additional Oversight and Raise Highlights of GAO-18-523, a report to Regulatory Questions congressional committees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found The Navy is planning to dismantle and The Navy is assessing two options to dismantle and dispose of its first nuclear- dispose of CVN 65 after 51 years of powered aircraft carrier—ex-USS Enterprise (also known as CVN 65). CVN 65 service. In 2013, the estimated cost to dismantlement and disposal will set precedents for processes and oversight that complete the CVN 65 work as may inform future aircraft carrier dismantlement decisions. originally planned increased to well over $1 billion, leading the Navy to Characteristics of the Navy’s Potential CVN 65 Dismantlement and Disposal Options consider different dismantlement and Naval shipyard option Full commercial option disposal options. General approach Puget Sound Naval Shipyard Commercial company(ies) The Senate Report accompanying a dismantles a distinct section of the dismantles entire ship; potential bill for the National Defense ship—the propulsion space companies and work locations yet section—that contains the 8 to be determined Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 defueled reactors and all other included a provision for GAO to review Nuclear-related -

What Do Aoes Do When They Are Deployed? Center for Naval Analyses

CAB D0000255.A1 / Final May 2000 What Do AOEs Do When They Are Deployed? Burnham C. McCaffree, Jr. • Jay C. Poret Center for Naval Analyses 4401 Ford Avenue • Alexandria, Virginia 22302-1498 Copyright CNA Corporation/Scanned October 2002 Approved for distribution: May 2000 ,*&. KW^f s£^ ••—H. Dwight Lydtis, Jr.rDfffector USMC & Expeditionary Systems Team Acquisition, Technology & Systems Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED For copies of this document, call the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section (703) 824-2130 Copyright © 2000 The CNA Corporation What Do AOEs Do When They Are Deployed? The Navy has twelve aircraft carriers and eight fast combat support ships (AOEs) that were built to act as carrier battle group (CVBG) station ships. The multi-product AOE serves as a "warehouse" for fuel, ammunition, spare parts, provisions, and stores to other CVBG ships, especially the carrier. Currently, an AOE deploys with about four out of every five CVBGs on peacetime forward deployments. Prior to 1996, when there were only four AOEs, only two of every five CVBGs deployed with an AOE. That frequency could resume in the latter part of this decade when AOE-1 class ships are retired at the end of their 35-year service life. The combat logistics force (CLF) that supports forward deployed combatant ships consists of CVBG station ships and shuttle ships (oilers, ammunition ships, and combat stores ships) that resupply the station ships and the combatants as well.