Theatre of War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multimovepad Uitgetest

kom uiten in je streek LANDSCHAPSKRANT - VOORJAAR 2021 MULTIMOVEPAD UITGETEST chefop stapJürgen met Crombez WIE ZOEKT, DIE VINDT VOORWOORD NIEUWE STREKEN KOM BUITEN IN DE WESTHOEK! De lente is in het land! Gedaan met ons binnen te heeft geluk, want die vindt zijn gading op pagina 26 met verstoppen voor de koude – en voor corona. We kunnen tips over ‘de grote goesting’. terug buiten en moeten dat ook doen, want, voor wie het nog niet wist, het is gezond. Lees er alles over op pagina 21. Mogelijkheden genoeg in elk geval. Het nieuwe multimovepad in de Sixtusbossen ontdek je op pagina tien en een overzicht van zowat alle bestaande zoektochten in Jurgen Vanlerberghe de Westhoek staat op pagina 28. Wie de vele inspanningen Voorzitter Regionaal graag doorspoelt met een streekeigen drankje of hapje, Landschap Westhoek WEERZEGGERIJ 01. WEERZEGGERIJ “Rood bij het rijzen, is regen voor de avond” is één 02. DE SINT-NIKLAASKERK IN MESEN © JAN D’HONDT BAD INHOUD van de 601 weerspreuken die Radio 2 weerman Geert 03. LAAT HET ZOEMEN MET Naessens niet alleen bevestigt, maar ook uitlegt in zijn BLOEMEN boek ‘Weerzeggerij’. De spreuken zijn een soort van 3 | NIEUWE STREKEN volksweerkunde. En al is het geen wetenschap, toch houden sommige stellingen steek. ‘Weerzeggerij’ is een 5 | DRIE BIJZONDERE KIJKWANDEN 20 | OPROEP: VRIJWILLIGERS GEZOCHT boek dat verrassende verhalen bij het weer brengt aan de hand van gezegden. 6 | INTERVIEW 21 | IN DE KIJKER: NATUUR MET ZORG www.geertnaessens.be/weerzeggerij | DE FIETS OP 8 24 | ONDER DE LOEP: BEEKVALLEIEN BEKLIM DE SINT-NIKLAASTOREN IN VEURNE… Geniet van het prachtig panoramisch 360° uitzicht | UITGETEST! MULTIMOVEPAD | OP STAP MET.. -

Kritak DE SCHOOL VAN DE LITERATUUR

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/104329 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-30 and may be subject to change. DE SCHOOL VAN DE LITERATUUR TOM LANOYE In. Ned Jos Joosten 16512 SUN· K rita k DE SCHOOL VAN DE LITERATUUR onder redactie van Eric Wagemans & Henk Peters Jos Joosten TOM LAN OYE De ontoereikendheid van het abstracte Paul Sars ADRIAAN VAM DIS De zandkastelen van je jeugd Omslagfoto voor de uitgave in eigen beheer Gent-Wevelgem-Gent, 1982 2 ^ ¿C 4 N O /óf "7 Jos Joosten T© M LANOYE De ontoereikendheid van het abstracte SUN · KRITAK 'V .'K M . ltsn- Het fotomateriaal is afkomstig uit de collectie van Tom Lanoye, Antwerpen Foto’s: Philip Boël, p. 63, 83 (rechts) - Willy Dé, Gent, p. 2,13 - Michiel Hendryckx, Gent, p. 33, 43, 57, 77 (rechts) - Fotoagentschap Luc Peeters, Lier, p. 92 - Gerrit Semé & partner, Amsterdam, p. 89 - Patrick de Spiegelaere, p. 49, 65, 77 (links) - Ben Wind, Rotterdam, p. 83 (links) Omslagontwerp en boekverzorging: Leo de Bruin, Amsterdam © Uitgeverij sun, Nijmegen 1996 ISBN 90 6168 4854 NUGI 321 Voor België Uitgeverij Kritak ISBN 90 6303 698 i D 1996 2393 45 EX UBRIS UNIVERStTATfê NOVIOMAGENSiS ínhoud 1. SLAGERSZOON MET DIVERSE BRILLEN Leven en literatuur 7 Middenstandsblues ? 8 Literaire leerschool 9 En publiceren maar 11 Maatschappelijke engagement 14 2. ‘we zijn a l l e e n en w e gaan k a p o t ’ Literatuur als ambacht 17 Lanoyes banale programma 18 Het banale banale 20 Afkeer van hoogdravendheid 20 De performer 23 De zin van het banale 24 De ontwikkeling van Lanoyes denken 28 3. -

Toerisme Heuvelland

EN HEUVELLAND WHERE TO HEUVELLAND PALETTE OF POSSIBILITIES This brochure will guide you through the wide range of activities, sights and tourist entrepreneurs in our region. Because Heuvelland is very versatile and every village has its own assets. De Klijte p. 5 Westouter p. 20 Dranouter p. 7 Wijtschate p. 25 Kemmel p. 11 Wulvergem p. 28 Loker p. 15 Recreation p. 30 Nieuwkerke p. 17 DO NOT MISS: Start your visit to Heuvelland in the child-friendly visitors’ center, where the landscape surrounding the Kemmelberg is explained. A wide selection of evocative images and tailor-made tourist information can help you to plan your unforgettable stay in Heuvelland. Address: Sint-Laurentiusplein 1, B-8950 Kemmel (Heuvelland) Jean-Pierre Geelhand de Merxem Alderman for Tourism All routes in this guide are available at the visitors’ centre. 1 LEGEND Info Points: The Info Points are dynamic restaurant owners, café Charming villages: The Westhoek and French owners or tourist entrepreneurs who, Flanders have a large amount of quietly as true ambassadors, give personal enchanted villages. Some of those pearls are even tips to their customers about what more beautiful than their already very impressive can be experienced in the region. colleagues. Those places were given the label Thor & Tess: child-friendly activities ‘charming village’. Brown taverns/restaurants: In the Westhoek you will find a lot of authentic, cozy brown taverns/ restaurants where you can catch Vintage Heuvelland Ambassadors are your breath and enjoy a nice local restaurateurs, every one of them a top professional, beer or wine and a local snack. who each in their own unique and passionate way Taste the cosiness and atmosphere work with wines from the Westhoek. -

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

How Did Two Bullets Kill 20 Million? Things You Need to Know Before We Get Going…

How did two bullets kill 20 million? Things you need to know before we get going… Countries in Europe were becoming more and more suspicious of each other. Germany was jealous of Britain’s empire and wanted an empire of it’s own. The Balkan countries were up for grabs. Alsace-Lorraine – argued about for ages and ….. Weapons were being developed all across Europe. If that is too much to take in, just remember…. Countries in Europe were getting more and more greedy and They were VERY suspicious of “the other side”. Would you go to war… Our nation is attacked by a foreign military A nation with whom we have a mutual defense alliance is attacked Our President is assassinated by a terrorist from an unfriendly nation Our President tells us that a country is planning an imminent attack on us A country has just had a fundamentalist revolution and is sending fighters into oil-producing nations in the region An unfriendly nation has just successfully tested a nuclear weapon in violation of a signed UN agreement A US naval vessel is sunk in a foreign harbor by government agents from that country Observe the two maps: What empires are missing? What can this tell us about the outcome of the war? Other Causes: Alliances What differences do you notice about By 1914 all the major thispowers map, were and linked the by a system of alliances. Europe today? The alliances made it more likely that a war would start. Once started, the alliances made it more likely to spread. -

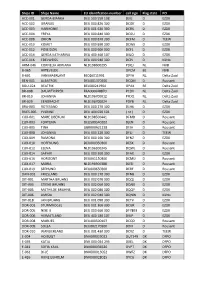

Ships ID Ships Name EU Identifcation Number Call Sign Flag State PO ACC

Ships ID Ships Name EU identifcation number call sign Flag state PO ACC-001 GERDA-BIANKA DEU 500 550 108 DJIG D EZDK ACC-002 URANUS DEU 000 820 300 DCGK D EZDK ACC-003 HARMONIE DEU 001 630 300 DCRK D EZDK ACC-004 FREYA DEU 000 840 300 DCGU D EZDK ACC-008 ORION DEU 000 870 300 DCFM D TEEW ACC-010 KOMET DEU 000 890 300 DCWK D EZDK ACC-012 POSEIDON DEU 000 900 300 DCFL D EZDK ACC-014 GERDA KATHARINA DEU 400 460 107 DIUO D EZDK ACC-016 EDELWEISS DEU 000 940 300 DCPJ D KüNo ARM-046 CORNELIA ADRIANA NLD198600295 PDQJ NL NVB B-065 ARTEVELDE OPCM BE NVB B-601 VAN MAERLANT BE026011991 OPYA NL Delta Zuid BEN-001 ALBATROS DEU001370300 DCQM D Rousant BOU-024 BEATRIX BEL000241964 OPAX BE Delta Zuid BR-008 DAUWTRIPPER FRA000648870 PCDV NL Delta Zuid BR-010 JOHANNA NLD196700012 PFDQ NL Delta Zuid BR-029 EENDRACHT NLD196700024 PDYB NL Delta Zuid BRA-003 ROTESAND DEU 000 270 300 DLHX D EZDK BUES-005 YVONNE DEU 404 020 101 ( nc ) D EZDK CUX-001 MARE LIBERUM NLD198500441 DFMD D Rousant CUX-003 FORTUNA DEU500540102 DJEN D Rousant CUX-005 TINA GBR000A21228 DFJH D Rousant CUX-008 JOHANNA DEU 000 220 300 DFLJ D TEEW CUX-009 RAMONA DEU 000 160 300 DFNZ D EZDK CUX-010 HOFFNUNG DEU000350300 DESX D Rousant CUX-012 ELENA NLD196300345 DQWL D Rousant CUX-014 SAPHIR DEU 000 360 300 DFAX D EZDK CUX-016 HORIZONT DEU001150300 DCMU D Rousant CUX-017 MARIA NLD196900388 DJED D Rousant CUX-019 SEEHUND DEU000650300 DERF D Rousant DAN-001 FRIESLAND DEU 000 170 300 DFNB D EZDK DIT-001 MARTHA BRUHNS DEU 002 070 300 DQQJ D EZDK DIT-003 STIENE BRUHNS DEU 002 060 300 DQNX D EZDK -

Service Above Self the ROTATOR ROTARY CLUB of SOUTHPORT

THE ROTATOR of the ROTARY CLUB OF SOUTHPORT District: 9640 Queensland,Chartered 20 Australiath August, 1945 16 May 2017 th Chartered 20 August 1945 Charter No: 6069 www.southportaustraliarotary.org Club No 17905 Service Above Self th Presidents Message for the Rotator of the 16 of May ROSTER 16 May I feel I am still coming down from a post Conference high, I think the best I have been to in my thirty nine Chr Michael I years and a special thankyou to DG Michael and to my Southport Rotary mates for a strong attendance and Sgt NA organizing and manning the registration desk. We’re a good team and I think did a dam good job. Atnd Jim S I am really drawn to people who don’t have a job, but RI President have a vocation, a calling and with it a dedication to Trs Tony S John Germ make a difference in people’s lives, and so it was with Rt Mn NA Nicole and Camille from Currumbin Special School, last night. I am sure we all felt privileged to be able to assist In Tst Lea R in some small way in the development and care of these special children. Th ks Greg D We had some fabulous speakers at the conference in Kerry O’Brien, Ita Buttrose and Noel Pearson but I have Up/Dn Lionel P to say the speakers I enjoyed the most were Rotarians, in particular Past President of RI, Bill Boyd and RI Director Scribe Allan T Noel Travaskis. A few gems for me from Bill Boyd: 3.6 DG Michael Irving billion people on our planet do not have access to clean water, largely due to poor sanitation leading to contamination of the water supply, leading to the deaths of 6,000 people a day from water borne diseases. -

PRESS RELEASE AEDIFICA Acquisition of a Rest Home in Ostend

PRESS RELEASE 8 September 2017 – after closing of markets Under embargo until 17:40 CET AEDIFICA Public limited liability company Public regulated real estate company under Belgian law Registered office: avenue Louise 331-333, 1050 Brussels Enterprise number: 0877.248.501 (RLE Brussels) (the “Company”) Acquisition of a rest home in Ostend, Belgium - Acquisition of a rest home in Ostend (Province of West Flanders, Belgium), comprising 115 units - Contractual value: approx. €12 million - Initial gross rental yield: approx. 5.5 % - Operator: Dorian group Stefaan Gielens, CEO of Aedifica, commented: "Thanks to the acquisition of this rest home, Aedifica continues to expand its Belgian healthcare real estate portfolio. The site is operational, nevertheless Aedifica will invest in renovation and extension works. This investment marks the first co-operation with the Dorian group. Other investments will follow.” 1/6 PRESS RELEASE 8 September 2017 – after closing of markets Under embargo until 17:40 CET Aedifica is pleased to announce the acquisition of a rest home in Belgium, pursuant to a previously established agreement1. De Duinpieper – Ostend Description of the site The De Duinpieper2 rest home is located in the “Vuurtorenwijk” neighbourhood in Ostend (70,000 inhabitants, Province of West Flanders). The building, designed by famous Belgian architect Lucien Kroll, was built in 1989. The site will be renovated into a modern residential care facility intended for seniors requiring continuous care, and extension works will be carried out for the construction of a new wing. Aedifica has budgeted approx. €2 million for these works. Upon completion of the works, as anticipated in summer 2019, the rest home will be able to welcome 115 residents. -

Carte Du Reseau Netkaart

AMSTERDAM ROTTERDAM ROTTERDAM ROOSENDAAL Essen 4 ESSEN Hoogstraten Baarle-Hertog I-AM.A22 12 ANTWERPEN Ravels -OOST Wildert Kalmthout KALMTHOUT Wuustwezel Kijkuit Merksplas NOORDERKEMPEN Rijkevorsel HEIDE Zweedse I-AM.A21 ANTW. Kapellen Kaai KNOKKE AREA Turnhout Zeebrugge-Strand 51A/1 202 Duinbergen -NOORD Arendonk ZEEBRUGGE-VORMING HEIST 12 TURNHOUT ZEEBRUGGE-DORP TERNEUZEN Brasschaat Brecht North-East BLANKENBERGE 51A 51B Knokke-Heist KAPELLEN Zwankendamme Oud-Turnhout Blankenberge Lissewege Vosselaar 51 202B Beerse EINDHOVEN Y. Ter Doest Y. Eivoorde Y.. Pelikaan Sint-Laureins Retie Y. Blauwe Toren 4 Malle Hamont-Achel Y. Dudzele 29 De Haan Schoten Schilde Zoersel CARTE DU RESEAU Zuienkerke Hamont Y. Blauwe Toren Damme VENLO Bredene I-AM.A32 Lille Kasterlee Dessel Lommel-Maatheide Neerpelt 19 Tielen Budel WEERT 51 GENT- Wijnegem I-AM.A23 Overpelt OOSTENDE 50F 202A 273 Lommel SAS-VAN-GENT Sint-Gillis-Waas MECHELEN NEERPELT Brugge-Sint-Pieters ZEEHAVEN LOMMEL Overpelt ROERMOND Stekene Mol Oostende ANTWERPEN Zandhoven Vorselaar 50A Eeklo Zelzate 19 Overpelt- NETKAART Wommelgem Kaprijke Assenede ZELZATE Herentals MOL Bocholt BRUGGE Borsbeek Grobbendonk Y. Kruisberg BALEN- Werkplaatsen Oudenburg Jabbeke Wachtebeke Moerbeke Ranst 50A/5 Maldegem EEKLO HERENTALS kp. 40.620 WERKPLAATSEN Brugge kp. 7.740 Olen Gent Boechout Wolfstee 15 GEEL Y. Oostkamp Waarschoot SINT-NIKLAAS Bouwel Balen I-AM.A34 Boechout NIJLEN Y. Albertkanaal Kinrooi Middelkerke OOSTKAMP Evergem GENT-NOORD Sint-Niklaas 58 15 Kessel Olen Geel 15 Gistel Waarschoot 55 219 15 Balen BRUGGE 204 Belsele 59 Hove Hechtel-Eksel Bree Beernem Sinaai LIER Nijlen Herenthout Peer Nieuwpoort Y. Nazareth Ichtegem Zedelgem BEERNEM Knesselare Y. Lint ZEDELGEM Zomergem 207 Meerhout Schelle Aartselaar Lint Koksijde Oostkamp Waasmunster Temse TEMSE Schelle KONTICH-LINT Y. -

73 Lijn 73 : Gent - Deinze - De Panne

nmbs 73 Lijn 73 : Gent - Deinze - De Panne Stations en haltes • AGENT-SINT-PIETERS • YDE PINTE • YDEINZE • YAARSELE • YTIELT • YLICHTERVELDE • YKORTEMARK • YDIKSMUIDE • YVEURNE • YKOKSIJDE • CDE PANNE Dienstregelingen geldig vanaf 13.12.2020 Uitgave 13.06.2021 Conventionele tekens ì Rijdt tijdens de jaarlijkse vakantieperiodes 19.12.20 → 02.01.21 03.04.21 → 17.04.21 03.07.21 → 29.08.21 í Rijdt niet tijdens de jaarlijkse vakantieperiodes Rijdt tijdens de toeristische periode (zomer) èí 03.07.21 → 29.08.21 3 Op weekdagen, behalve feestdagen 4 Op zaterdagdagen, zon- en feestdagen ,...2 Maandag...Zondag ^ Zon- en feestdagen + Aankomstuur van de trein [ Diabolotoeslag van toepassing voor deze bestemming @ InterCitytrein ` Voorstadstrein = Lokale trein > Piekuurtrein ç Bus å Toeristische trein Ü Thalys trein à ICE trein (Deutsche Bahn) Feestdagen gelijkgesteld met een zondag : 25.12.20 - 01.01.21 - 05.04.21 - 01.05.21 - 13.05.21 - 24.05.21 - 21.07.21 - 01.11.21 - 11.11.21 Brugdagen waarop de treindienst kan worden aangepast : Op 14.05.21 en 12.11.21 Voor de laatste updates : Plan uw reis via de NMBS-app of nmbs.be Maandag tot vrijdag, behalve op feestdagen 73 Gent - Deinze - De Panne @ @ @ å @ @ @ @ 3004 3005 3006 6901 3007 3008 3009 3010 è Herkomst Antw. Antw. Antw. Antw. Antw. Cent. Cent. Cent. Cent. Cent. 6.50 7.51 8.51 9.51 10.51 Brus.-Noord 7.27 Brus.-Centraal 7.32 Brus.-Zuid 7.45 Gent-Sint-Pieters + 8.14 Gent-Sint-Pieters 5.53 6.53 7.53 8.21 8.53 9.53 10.53 11.53 De Pinte + 6.00 7.00 8.00 8.28 9.00 10.00 11.00 12.00 De Pinte 6.01 7.01 -

Adressen Diensten Voor Oppashulp West-Vlaanderen Repertorium Diensten Voor Oppashulp West-Vlaanderen

Agentschap Zorg en Gezondheid Afdeling Preventie, Eerstelijn en Thuiszorg Koning Albert II-laan 35 bus 33, 1030 Brussel Tel. 02-553 36 47 - Fax 02 553 36 05 Adressen Diensten voor Oppashulp West-Vlaanderen Repertorium Diensten voor Oppashulp West-Vlaanderen Voorziening Beheersinstantie BRUGGE Familiezorg West-Vlaanderen Regio Brugge- Familiezorg West-Vlaanderen Oostende Dossiernr.: 502 VZW Erkenningsnr.: OPP502 Sint-Jansplein 8 Biskajersplein 3 8000 Brugge 8000 Brugge tel. : fax: website: e-mail: Oppas Regio Brugge-Oostende Oppas Dossiernr.: 522 VZW Erkenningsnr.: OPP522 Oude Burg 27 Oude Burg 27 8000 Brugge 8000 Brugge tel. : fax: website: e-mail: Pagina 2 van 9 6-sep-21 Agentschap Zorg en Gezondheid Afdeling Woonzorg en Eerste Lijn Koning Albert II-laan 35 bus 33, 1030 Brussel Tel. 02-553 36 47 - Fax 02 553 36 05 Repertorium Diensten voor Oppashulp West-Vlaanderen Voorziening Beheersinstantie IEPER Familiezorg West-Vlaanderen Regio Veurne- Familiezorg West-Vlaanderen Diksmuide-Ieper Dossiernr.: 503 VZW Erkenningsnr.: OPP503 De Brouwerstraat 4 Biskajersplein 3 8900 Ieper 8000 Brugge tel. : fax: website: e-mail: Pagina 3 van 9 6-sep-21 Agentschap Zorg en Gezondheid Afdeling Woonzorg en Eerste Lijn Koning Albert II-laan 35 bus 33, 1030 Brussel Tel. 02-553 36 47 - Fax 02 553 36 05 Repertorium Diensten voor Oppashulp West-Vlaanderen Voorziening Beheersinstantie KORTRIJK Oppas Zuid-West-Vlaanderen OPPAS ZUID-WEST-VLAANDEREN Dossiernr.: 513 VZW Erkenningsnr.: OPP513 Beneluxpark 22 Beneluxpark(Kor) 22 8500 Kortrijk 8500 Kortrijk tel. : fax: website: e-mail: i-mens Regio Kortrijk-Roeselare-Tielt i-mens Dossiernr.: 526 VZW Erkenningsnr.: OPP526 't Hoge 49 Tramstraat 61 8500 Kortrijk 9052 Gent tel. -

District 112 A.Pdf

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF JANUARY 2021 CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR MEMBERSHI P CHANGES TOTAL DIST IDENT NBR CLUB NAME COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3599 021928 AALST BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 29 0 0 0 -1 -1 28 3599 021937 OUDENAARDE BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 58 0 0 0 -2 -2 56 3599 021942 BLANKENBERGE BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 32 0 0 0 0 0 32 3599 021944 BRUGGE BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 28 0 0 0 0 0 28 3599 021945 BRUGGE ZEEHAVEN BELGIUM 112 A 7 12-2020 29 0 0 0 -4 -4 25 3599 021960 KORTRIJK BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 51 1 0 0 -2 -1 50 3599 021961 DEINZE BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 28 1 0 0 -3 -2 26 3599 021971 GENT GAND BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 67 0 0 0 0 0 67 3599 021972 GENT SCALDIS BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 54 0 0 0 -3 -3 51 3599 021976 GERAARDSBERGEN BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 38 1 0 0 -1 0 38 3599 021987 KNOKKE ZOUTE BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 27 0 0 0 -1 -1 26 3599 021991 DE PANNE WESTKUST BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 40 0 0 0 0 0 40 3599 022001 MEETJESLAND EEKLO L C BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 37 0 0 0 0 0 37 3599 022002 MENIN COMINES WERVIC BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 39 0 0 0 -1 -1 38 3599 022009 NINOVE BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 40 2 0 0 -3 -1 39 3599 022013 OOSTENDE BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 45 0 0 0 -1 -1 44 3599 022018 RONSE-RENAIX BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 58 3 0 0 0 3 61 3599 022019 ROESELARE BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 50 0 0 0 0 0 50 3599 022020 WETTEREN ROZENSTREEK BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021 40 1 0 0 0 1 41 3599 022021 WAASLAND BELGIUM 112 A 4 01-2021