Indo 12 0 1107125075 151

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Transforming Sundanese Script: from Palm Leaf to Digital Typography

Transforming Sundanese Script: From Palm Leaf to Digital Typography PRESENTER’S IDENTITY HERE Name: Agung Zainal M. Raden, Rustopo, Timbul Haryono Affiliation: Program Doktor ISI Surakarta Abstract Code: ABS-ICOLLITE-20026 Transforming Sundanese Script: From Palm Leaf to Digital Typography AGUNG ZAINAL MUTTAKIN RADEN, RUSTOPO, TIMBUL HARYONO ABSTRACT The impact of globalisation is the lost of local culture, transformation is an attempt to offset the global culture. This article will discuss the transformation process from the Sundanese script contained in palm leaf media to the modern Sundanese script in the form of digital typography. The method used is transformation, which can be applied to rediscover the ancient Sundanese script within the new form known as the modern Sundanese script that it is relevant to modern society. Transformation aims to maintain local culture from global cultural domination. This article discovers the way Sundanese people reinvent their identity through the transformation from ancient Sundanese script to modern Sundanese script by designing a new form of script in order to follow the global technological developments. Keywords: Sundanese script, digital typography, transformation, reinventing, globalisation INTRODUCTION Sundanese ancient handwriting in palm leaf manuscripts is one of the cultural heritage that provides rich knowledge about past, recent, and the future of the Sundanese. The Sundanese script is a manifestation of Sundanese artefacts that contain many symbols and values Digitisation is the process of transforming analogue material into binary electronic (digital) form, especially for storage and use in a computer The dataset consists of three type of data: annotation at word level, annotation at character level, and binarised images Unicode is a universal character encoding standard used for representation of text for computer processing METHODS Transforming: Aims to reinvent an old form of tradition so that it fits into and suits contemporary lifestyles. -

Scanned by Camscanner Scanned by Camscanner Scanned by Camscanner Page 1

Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Page 1 School-wise pending status of Registration of Class 9th and 11th 2017-18 (upto 10-10-2017) Sl. Dist Sch SchoolName Total09 Entry09 pending_9th Total11 Entry11 1 01 1019 D A V INT COLL DHIMISHRI AGRA 75 74 1 90 82 2 01 1031 ROHTA INT COLL ROHTA AGRA 100 92 8 100 90 3 01 1038 NAV JYOTI GIRLS H S S BALKESHWAR AGRA 50 41 9 0 4 01 1039 ST JOHNS GIRLS INTER COLLEGE 266 244 22 260 239 5 01 1053 HUBLAL INT COLL AGRA 100 21 79 110 86 6 01 1054 KEWALRAM GURMUKHDAS INTER COLLEGE AGRA 200 125 75 200 67 7 01 1057 L B S INT COLL MADHUNAGAR AGRA 71 63 8 48 37 8 01 1064 SHRI RATAN MUNI JAIN INTER COLLEGE AGRA 392 372 20 362 346 9 01 1065 SAKET VIDYAPEETH INTERMEDIATE COLLEGE SAKET COLONY AGRA 150 64 86 200 32 10 01 1068 ST JOHNS INTER COLLEGE HOSPITAL ROAD AGRA 150 129 21 200 160 11 01 1074 SMT V D INT COLL GARHI RAMI AGRA 193 189 4 152 150 12 01 1085 JANTA INT COLL FATEHABAD AGRA 114 108 6 182 161 13 01 1088 JANTA INT COLL MIDHAKUR AGRA 111 110 1 75 45 14 01 1091 M K D INT COLL ARHERA AGRA 98 97 1 106 106 15 01 1092 SRI MOTILAL INT COLL SAIYAN AGRA 165 161 4 210 106 16 01 1095 RASHTRIYA INT COLL BARHAN AGRA 325 318 7 312 310 17 01 1101 ANGLO BENGALI GIRLS INT COLL AGRA 150 89 61 150 82 18 01 1111 ANWARI NELOFER GIRLS I C AGRA 60 55 5 65 40 19 01 1116 SMT SINGARI BAI GIRLS I C BALUGANJ AGRA 70 60 10 100 64 20 01 1120 GOVT GIRLS INT COLL ANWAL KHERA AGRA 112 107 5 95 80 21 01 1121 S B D GIRLS INT COLL FATEHABAD AGRA 105 104 1 47 47 22 01 1122 SHRI RAM SAHAY VERMA INT COLL BASAUNI -

CHAPTER – I : INTRODUCTION 1.1 Importance of Vamiki Ramayana

CHAPTER – I : INTRODUCTION 1.1 Importance of Vamiki Ramayana 1.2 Valmiki Ramayana‘s Importance – In The Words Of Valmiki 1.3 Need for selecting the problem from the point of view of Educational Leadership 1.4 Leadership Lessons from Valmiki Ramayana 1.5 Morality of Leaders in Valmiki Ramayana 1.6 Rationale of the Study 1.7 Statement of the Study 1.8 Objective of the Study 1.9 Explanation of the terms 1.10 Approach and Methodology 1.11 Scheme of Chapterization 1.12 Implications of the study CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION Introduction ―The art of education would never attain clearness in itself without philosophy, there is an interaction between the two and either without the other is incomplete and unserviceable.‖ Fitche. The most sacred of all creations of God in the human life and it has two aspects- one biological and other sociological. If nutrition and reproduction maintain and transmit the biological aspect, the sociological aspect is transmitted by education. Man is primarily distinguishable from the animals because of power of reasoning. Man is endowed with intelligence, remains active, original and energetic. Man lives in accordance with his philosophy of life and his conception of the world. Human life is a priceless gift of God. But we have become sheer materialistic and we live animal life. It is said that man is a rational animal; but our intellect is fully preoccupied in pursuit of materialistic life and worldly pleasures. Our senses and objects of pleasure are also created by God, hence without discarding or condemning them, we have to develop ( Bhav Jeevan) and devotion along with them. -

The Creative Choreography for Nang Yai (Thai Traditional Shadow Puppet Theatre) Ramakien, Wat Ban Don, Rayong Province

Fine Arts International Journal, Srinakharinwirot University Vol.14 issue 2 July - December 2010 The Creative Choreography for Nang Yai (Thai traditional shadow puppet theatre) Ramakien, Wat Ban Don, Rayong Province Sun Tawalwongsri Abstract This paper aims at studying Nang Yai performances and how to create modernized choreography techniques for Nang Yai by using Wat Ban Don dance troupes. As Nang Yai always depicts Ramakien stories from the Indian Ramayana epic, this piece will also be about a Ramayana story, performed with innovative techniques—choreography, narrative, manipulation, and dance movement. The creation of this show also emphasizes on exploring and finding methods of broader techniques, styles, and materials that can be used in the production of Nang Yai for its development and survival in modern times. Keywords: NangYai, Thai traditional shadow puppet theatre, Choreography, Performing arts Introduction narration and dialogues, dance and performing art Nang Yai or Thai traditional shadow in the maneuver of the puppets along with musical puppet theatre, the oldest theatrical art in Thailand, art—the live music accompanying the shows. is an ancient form of storytelling and entertainment Shadow performance with puppets made using opaque, often articulated figures in front of from animal hide is a form of world an illuminated backdrop to create the illusion of entertainment that can be traced back to ancient moving images. Such performance is a combination times, and is believed to be approximately 2,000 of dance and puppetry, including songs and chants, years old, having been evolved through much reflections, poems about local events or current adjustment and change over time. -

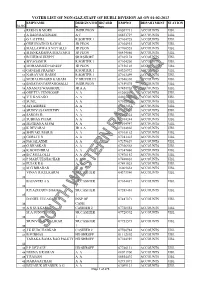

Hubli Voter List-2013

VOTER LIST OF NON-GAZ STAFF OF HUBLI DIVISION AS ON 01-02-2013 EMPNAME DESIGNATIO IDCARD EMPNO DEPARTMENT STATION SL.NO N NO 1 REKHA B MORE JMDR PEON 00207731 ACCOUNTS UBL 2 A BABURATHNAM A C 06431719 ACCOUNTS UBL 3 G LALITHA R SORTER 1 07104728 ACCOUNTS UBL 4 GURUNATH D RAWAL JD PEON 07104935 ACCOUNTS UBL 5 MALLAWWA S NITTALLI JD PEON 07760528 ACCOUNTS UBL 6 SHANKARAPPA M.KUDAGI JD PEON 06434060 ACCOUNTS UBL 7 B I HURALIKUPPI SR RSHORT 07105174 ACCOUNTS UBL 8 SIVAGAMI R R SORTER 1 07104200 ACCOUNTS UBL 9 MOHAMMED HANEEF JD PEON 07456104 ACCOUNTS UBL 10 GANESH PRASAD R SORTER 1 00328972 ACCOUNTS UBL 11 NARAYAN BADDI R SORTER 1 07103499 ACCOUNTS UBL 12 MURALIDHARD KADAM V DRIVER III 07348370 ACCOUNTS UBL 13 BASAVANTAPPAHOSALLI JMDR PEON 07459075 ACCOUNTS UBL 14 ANAND.S.WAGMORE JR A A 07450916 ACCOUNTS UBL 15 GRETTA PUNNOOSE A A 01206564 ACCOUNTS UBL 16 V V KANAGO A A 04695240 ACCOUNTS UBL 17 SUNIL A A 07102768 ACCOUNTS UBL 18 JAYASHREE A A 07103451 ACCOUNTS UBL 19 SRINIVASAMURTHY A A 07103463 ACCOUNTS UBL 20 SAROJA B A A 07104224 ACCOUNTS UBL 21 SUBHAS PUJAR A A 07104248 ACCOUNTS UBL 22 MEGHANA M PAI A A 07104947 ACCOUNTS UBL 23 K DEVARAJ JR A A 07104960 ACCOUNTS UBL 24 SHIVAKUMAR.B A A 07105162 ACCOUNTS UBL 25 GORLI V N A A 07241422 ACCOUNTS UBL 26 NAGALAXMI A A 07279619 ACCOUNTS UBL 27 G.BHASKAR A A 07306568 ACCOUNTS UBL 28 K.GOVINDRAJ A A 07347080 ACCOUNTS UBL 29 B.C.MULLOLLI A A 07476152 ACCOUNTS UBL 30 P MARUTESHACHAR A A 07488816 ACCOUNTS UBL 31 PUJAR R S A A 07491025 ACCOUNTS UBL 32 M G BIRADAR A A 16069638 ACCOUNTS UBL VINAY R -

Ebook-On-Sri-Venkateshwara-Kalyanam.Pdf

Discourse on Sri Venkateshwara Kalyanam – day 1 – Jan 25 2013 Sri Gurubhyo Namah ! Introduction by Pujya Sri Datta Vijayananda Theertha Swamiji Jaya Guru Datta! Jai Bolo Sadgurunath Maharaj Ki! Edukondalavada Venkata Ramana Govinda Govinda! Om Namo Datta Venkateshaya! Today all of us are blessed with an amazing event of starting of the discourse on the topic ”Sri Venkateswara Kalyanam” in this mgnificient Nada mantapa, by our Pujya Sadguru Deva. Last year, we listened to the same discourse in Kannada language. In this Nandana year of 2013, Sri Swamiji decided to bless all of us with a divine discourse of Srinivasa Kalyanam in Telugu considering all our pleadings and requests. This is a boon to all of us. It is a wonderful opportunity to all of us. Just now Pujya Appaji blessed all the devotees who arrived from different places. Those who want to stay back in the Ashrama to listen to “Srinivasa kalyanam” discourse and participate in the mandala puja of Lord Hanuman, can register their names in the office room. Make use of this rare opportunity. Now Sri Swamiji starts the divine discourse in His mellifluous and sonorous voice. As the webcast is going across the globe, and the Television channels, we have to observe certain rules for the best presentation of our programme. Kindly switch off your mobile phones. Try not to cough and those who have cough and cold are requested not to sit in the front rows. Let all the children sit at the back. It is not fair on our part to go away, while the discourse is going on. -

Documenting Endangered Alphabets

Documenting endangered alphabets Industry Focus Tim Brookes Three years ago, acting on a notion so whimsi- cal I assumed it was a kind of presenile monoma- nia, I began carving endangered alphabets. The Tdisclaimers start right away. I’m not a linguist, an anthropologist, a cultural historian or even a woodworker. I’m a writer — but I had recently started carving signs for friends and family, and I stumbled on Omniglot.com, an online encyclo- pedia of the world’s writing systems, and several things had struck me forcibly. For a start, even though the world has more than 6,000 Figure 1: Tifinagh. languages (some of which will be extinct even by the time this article goes to press), it has fewer than 100 scripts, and perhaps a passing them on as a series of items for consideration and dis- third of those are endangered. cussion. For example, what does a written language — any writ- Working with a set of gouges and a paintbrush, I started to ten language — look like? The Endangered Alphabets highlight document as many of these scripts as I could find, creating three this question in a number of interesting ways. As the forces of exhibitions and several dozen individual pieces that depicted globalism erode scripts such as these, the number of people who words, phrases, sentences or poems in Syriac, Bugis, Baybayin, can write them dwindles, and the range of examples of each Samaritan, Makassarese, Balinese, Javanese, Batak, Sui, Nom, script is reduced. My carvings may well be the only examples Cherokee, Inuktitut, Glagolitic, Vai, Bassa Vah, Tai Dam, Pahauh of, say, Samaritan script or Tifinagh that my visitors ever see. -

Uttarakandam

THE RAMAYANA. Translated into English Prose from the original Sanskrit of Valmiki. UTTARAKANDAM. M ra Oer ii > m EDITED AND PUBLISHED Vt MANMATHA NATH DUTT, MA. CALCUTTA. 1894. Digitized by VjOOQIC Sri Patmanabha Dasa Vynchi Bala Sir Rama Varma kulasekhara klritapatl manney sultan maha- RAJA Raja Ramraja Bahabur Shamshir Jung Knight Grand Commander of most Emi- nent order of the Star of India. 7gK afjaraja of ^xavancoxe. THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY MANMATHA NATH DUTT. In testimony of his veneration for His Highness and in grateful acknowledgement of the distinction conferred upon him while in His Highness* capital, and the great pecuniary help rendered by his Highness in publishing this work. Digitized by VjOOQ IC T — ^ 3oVkAotC UTTARA KlAlND^M, SECTION I. \Jn the Rakshasas having been slain, all the ascetics, for the purpose of congratulating Raghava, came to Rama as he gained (back) his kingdom. Kau^ika, and Yavakrita, and Gargya, and Galava, and Kanva—son unto Madhatithi, . who dwelt in the east, (came thither) ; aikl the reverend Swastyastreya, and Namuchi,and Pramuchi, and Agastya, and the worshipful Atri, aud Sumukha, and Vimukha,—who dwelt in the south,—came in company with Agastya.* And Nrishadgu, and Kahashi, and Dhaumya, and that mighty sage —Kau^eya—who abode in the western "quarter, came there accompanied by their disciples. And Vasishtha and Ka^yapa and Atri and Vicwamitra with Gautama and Jamadagni and Bharadwaja and also the seven sages,t who . (or aye resided in the northern quarter, (came there). And on arriving at the residence of Raghava, those high-souled ones, resembling the fire in radiance, stopped at the gate, with the intention of communicating their arrival (to Rama) through the warder. -

The Transformation of Thai Khon Costume Concept to High-End Fashion Design

THE TRANSFORMATION OF THAI KHON COSTUME CONCEPT TO HIGH-END FASHION DESIGN By Miss Hu JIA A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy DESIGN ARTS (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2020 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University - โดย MissHU JIA วทิ ยานิพนธ์น้ีเป็นส่วนหน่ึงของการศึกษาตามหลกั สูตรปรัชญาดุษฎีบณั ฑิต สาขาวิชาศิลปะการออกแบบ แบบ 1.1 ปรัชญาดุษฎีบัณฑิต(หลักสูตรนานาชาติ) บัณฑิตวิทยาลัย มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร ปีการศึกษา 2563 ลิขสิทธ์ิของบณั ฑิตวทิ ยาลยั มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร THE TRANSFORMATION OF THAI KHON COSTUME CONCEPT TO HIGH-END FASHION DESIGN By Miss Hu JIA A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy DESIGN ARTS (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2020 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University Title THE TRANSFORMATION OF THAI KHON COSTUME CONCEPT TO HIGH-END FASHION DESIGN By Hu JIA Field of Study DESIGN ARTS (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) Advisor Assistant Professor JIRAWAT VONGPHANTUSET , Ph.D. Graduate School Silpakorn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Dean of graduate school (Associate Professor Jurairat Nunthanid, Ph.D.) Approved by Chair person (Professor Eakachat Joneurairatana ) Advisor (Assistant Professor JIRAWAT VONGPHANTUSET , Ph.D.) Co advisor (Assistant Professor VEERAWAT SIRIVESMAS , Ph.D.) External Examiner (Professor Mustaffa Hatabi HJ. Azahari , Ph.D.) D ABST RACT 60155903 : Major DESIGN -

Development Production Line the Short Story

Development Production Line The Short Story Jene Jasper Copyright © 2007-2018 freedumbytes.dev.net (Free Dumb Bytes) Published 3 July 2018 4.0-beta Edition While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this installation manual, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To get an idea of the Development Production Line take a look at the following Application Integration overview and Maven vs SonarQube Quality Assurance reports comparison. 1. Operating System ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Windows ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1. Resources ................................................................................................ 1 1.1.2. Desktop .................................................................................................. 1 1.1.3. Explorer .................................................................................................. 1 1.1.4. Windows 7 Start Menu ................................................................................ 2 1.1.5. Task Manager replacement ........................................................................... 3 1.1.6. Resource Monitor ..................................................................................... -

Sita Ram Baba

सीता राम बाबा Sītā Rāma Bābā סִיטָ ה רְ אַמָ ה בָבָ ה Bābā بَابَا He had a crippled leg and was on crutches. He tried to speak to us in broken English. His name was Sita Ram Baba. He sat there with his begging bowl in hand. Unlike most Sadhus, he had very high self- esteem. His eyes lit up when we bought him some ice-cream, he really enjoyed it. He stayed with us most of that evening. I videotaped the whole scene. Churchill, Pola (2007-11-14). Eternal Breath : A Biography of Leonard Orr Founder of Rebirthing Breathwork (Kindle Locations 4961-4964). Trafford. Kindle Edition. … immortal Sita Ram Baba. Churchill, Pola (2007-11-14). Eternal Breath : A Biography of Leonard Orr Founder of Rebirthing Breathwork (Kindle Location 5039). Trafford. Kindle Edition. Breaking the Death Habit: The Science of Everlasting Life by Leonard Orr (page 56) ראמה راما Ράμα ראמה راما Ράμα Rama has its origins in the Sanskrit language. It is used largely in Hebrew and Indian. It is derived literally from the word rama which is of the meaning 'pleasing'. http://www.babynamespedia.com/meaning/Rama/f Rama For other uses, see Rama (disambiguation). “Râm” redirects here. It is not to be confused with Ram (disambiguation). Rama (/ˈrɑːmə/;[1] Sanskrit: राम Rāma) is the seventh avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu,[2] and a king of Ayodhya in Hindu scriptures. Rama is also the protagonist of the Hindu epic Ramayana, which narrates his supremacy. Rama is one of the many popular figures and deities in Hinduism, specifically Vaishnavism and Vaishnava reli- gious scriptures in South and Southeast Asia.[3] Along with Krishna, Rama is considered to be one of the most important avatars of Vishnu.