Feeding Habits of Extant and Fossil Canids As Determined by Their Skull Geometry C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Large Terrestrial Carnivores on Pleistocene Ecosystems Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Matthew W

The impact of large terrestrial carnivores on SPECIAL FEATURE Pleistocene ecosystems Blaire Van Valkenburgha,1, Matthew W. Haywardb,c,d, William J. Ripplee, Carlo Melorof, and V. Louise Rothg aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; bCollege of Natural Sciences, Bangor University, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 2UW, United Kingdom; cCentre for African Conservation Ecology, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa; dCentre for Wildlife Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa; eTrophic Cascades Program, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331; fResearch Centre in Evolutionary Anthropology and Palaeoecology, School of Natural Sciences and Psychology, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L3 3AF, United Kingdom; and gDepartment of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0338 Edited by Yadvinder Malhi, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom, and accepted by the Editorial Board August 6, 2015 (received for review February 28, 2015) Large mammalian terrestrial herbivores, such as elephants, have analogs, making their prey preferences a matter of inference, dramatic effects on the ecosystems they inhabit and at high rather than observation. population densities their environmental impacts can be devas- In this article, we estimate the predatory impact of large (>21 tating. Pleistocene terrestrial ecosystems included a much greater kg, ref. 11) Pleistocene carnivores using a variety of data from diversity of megaherbivores (e.g., mammoths, mastodons, giant the fossil record, including species richness within guilds, pop- ground sloths) and thus a greater potential for widespread habitat ulation density inferences based on tooth wear, and dietary in- degradation if population sizes were not limited. -

Shape Evolution and Sexual Dimorphism in the Mandible of the Dire Wolf, Canis Dirus, at Rancho La Brea Alexandria L

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2014 Shape evolution and sexual dimorphism in the mandible of the dire wolf, Canis Dirus, at Rancho la Brea Alexandria L. Brannick [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Brannick, Alexandria L., "Shape evolution and sexual dimorphism in the mandible of the dire wolf, Canis Dirus, at Rancho la Brea" (2014). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 804. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHAPE EVOLUTION AND SEXUAL DIMORPHISM IN THE MANDIBLE OF THE DIRE WOLF, CANIS DIRUS, AT RANCHO LA BREA A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences by Alexandria L. Brannick Approved by Dr. F. Robin O’Keefe, Committee Chairperson Dr. Julie Meachen Dr. Paul Constantino Marshall University May 2014 ©2014 Alexandria L. Brannick ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my advisor, Dr. F. Robin O’Keefe, for all of his help with this project, the many scientific opportunities he has given me, and his guidance throughout my graduate education. I thank Dr. Julie Meachen for her help with collecting data from the Page Museum, her insight and advice, as well as her support. I learned so much from Dr. -

Mammalia, Felidae, Canidae, and Mustelidae) from the Earliest Hemphillian Screw Bean Local Fauna, Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas

Chapter 9 Carnivora (Mammalia, Felidae, Canidae, and Mustelidae) From the Earliest Hemphillian Screw Bean Local Fauna, Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas MARGARET SKEELS STEVENS1 AND JAMES BOWIE STEVENS2 ABSTRACT The Screw Bean Local Fauna is the earliest Hemphillian fauna of the southwestern United States. The fossil remains occur in all parts of the informal Banta Shut-in formation, nowhere very fossiliferous. The formation is informally subdivided on the basis of stepwise ®ning and slowing deposition into Lower (least fossiliferous), Middle, and Red clay members, succeeded by the valley-®lling, Bench member (most fossiliferous). Identi®ed Carnivora include: cf. Pseudaelurus sp. and cf. Nimravides catocopis, medium and large extinct cats; Epicyon haydeni, large borophagine dog; Vulpes sp., small fox; cf. Eucyon sp., extinct primitive canine; Buisnictis chisoensis, n. sp., extinct skunk; and Martes sp., marten. B. chisoensis may be allied with Spilogale on the basis of mastoid specialization. Some of the Screw Bean taxa are late survivors of the Clarendonian Chronofauna, which extended through most or all of the early Hemphillian. The early early Hemphillian, late Miocene age attributed to the fauna is based on the Screw Bean assemblage postdating or- eodont and predating North American edentate occurrences, on lack of de®ning Hemphillian taxa, and on stage of evolution. INTRODUCTION southwestern North America, and ®ll a pa- leobiogeographic gap. In Trans-Pecos Texas NAMING AND IMPORTANCE OF THE SCREW and adjacent Chihuahua and Coahuila, Mex- BEAN LOCAL FAUNA: The name ``Screw Bean ico, they provide an age determination for Local Fauna,'' Banta Shut-in formation, postvolcanic (,18±20 Ma; Henry et al., Trans-Pecos Texas (®g. -

New Eucyon Remains from the Pliocene Aramis Member (Sagantole Formation), Middle Awash Valley (Ethiopia)

New Eucyon remains from the Pliocene Aramis Member (Sagantole Formation), Middle Awash Valley (Ethiopia) Nuria Garcia Department Paleontologfa and Centra de Evoluci6n y Comportamiento Humanos, lnstituto de Salud Carlo,l' Ill, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, ClSinesio Delgado4, Pabell6n 14,28029 Madrid, Spain Abstract The Aramis Member (Sagantole formation) includes the Gaala Tuff Complex-Daam Aatu Basaltic Tuff interval which has produced a taxonomically diverse vertebrate assemblage including the primitive hominid Ardipithecus ramidus. New Eucyon remains recovered from this interval come from localities in the Aramis, Sagantole, and Kuseralee catchments. The chronology established for the GATC-DAB T interval is 4.4 Ma. These recoveries represent the most abundant available Eucyon assemblage of the eastern African Pliocene. Here, Eucyon fossils from the Kapsomin and Lemudong'o Late Miocene Kenyan sites are compared with the Aramis representatives, showing comparable morphology although with smaller dimensions. E. intrepidus-E. wokari novo sp., might constitute a single lineage, with increasing size and robusticity, and the derivation of some morphological traits mainly on the lower carnassial. E. wokari represents a new eastern species of the African Pliocene Eucyon lineage. Resume Nouveaux restes d'Eucyon dans le Membre Aramis pliocene (Formation Sagantole) de la moyenne vallee de l'Awash (Ethiopie). Le membre Aramis de la formation Sagantole inclut le «Galaa Tuff Complex-Daam Aatu Basaltic Tuff interval» qui a livre un ensemble varie de vertebres, y compris l'hominide primitif Ardipithecus ramidus. De nouveaux restes d' Eucyon recoltes dans cet intervalle proviennent de localites des stations d' Aramis, Sagantole et Kuseralee. L'age de I'intervalle est de 4,4 Ma. -

Entre Chien Et Loup

ANNEE 2003 THESE : 2003 – TOU 3 – 4102 ENTRE CHIEN ET LOUP : ETUDE BIOLOGIQUE ET COMPORTEMENTALE _________________ THESE pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR VETERINAIRE DIPLOME D’ETAT présentée et soutenue publiquement en 2003 devant l’Université Paul-Sabatier de Toulouse par Laurent, Sylvain, Patrice NEAULT Né, le 7 janvier 1976 à BELFORT (Territoire de Belfort) ___________ Directeur de thèse : M. le Professeur Roland DARRE ___________ JURY PRESIDENT : M. Henri DABERNAT Professeur à l’Université Paul-Sabatier de TOULOUSE ASSESSEUR : M. Roland DARRE Professeur à l’Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de TOULOUSE M. Guy BODIN Professeur à l’Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de TOULOUSE MINISTERE DE L'AGRICULTURE ET DE LA PECHE ECOLE NATIONALE VETERINAIRE DE TOULOUSE Directeur : M. P. DESNOYERS Directeurs honoraires……. : M. R. FLORIO M. J. FERNEY M. G. VAN HAVERBEKE Professeurs honoraires….. : M. A. BRIZARD M. L. FALIU M. C. LABIE M. C. PAVAUX M. F. LESCURE M. A. RICO M. A. CAZIEUX Mme V. BURGAT M. D. GRIESS PROFESSEURS CLASSE EXCEPTIONNELLE M. CABANIE Paul, Histologie, Anatomie pathologique M. CHANTAL Jean, Pathologie infectieuse M. DARRE Roland, Productions animales M. DORCHIES Philippe, Parasitologie et Maladies Parasitaires M. GUELFI Jean-François, Pathologie médicale des Equidés et Carnivores M. TOUTAIN Pierre-Louis, Physiologie et Thérapeutique PROFESSEURS 1ère CLASSE M. AUTEFAGE André, Pathologie chirurgicale M. BODIN ROZAT DE MANDRES NEGRE Guy, Pathologie générale, Microbiologie, Immunologie M. BRAUN Jean-Pierre, Physique et Chimie biologiques et médicales M. DELVERDIER Maxence, Histologie, Anatomie pathologique M. EECKHOUTTE Michel, Hygiène et Industrie des Denrées Alimentaires d'Origine Animale M. EUZEBY Jean, Pathologie générale, Microbiologie, Immunologie M. FRANC Michel, Parasitologie et Maladies Parasitaires M. -

Coyote Canis Latrans in 2007 IUCN Red List (Canis Latrans)

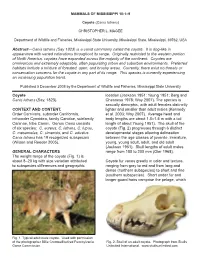

MAMMALS OF MISSISSIPPI 10:1–9 Coyote (Canis latrans) CHRISTOPHER L. MAGEE Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, Mississippi, 39762, USA Abstract—Canis latrans (Say 1823) is a canid commonly called the coyote. It is dog-like in appearance with varied colorations throughout its range. Originally restricted to the western portion of North America, coyotes have expanded across the majority of the continent. Coyotes are omnivorous and extremely adaptable, often populating urban and suburban environments. Preferred habitats include a mixture of forested, open, and brushy areas. Currently, there exist no threats or conservation concerns for the coyote in any part of its range. This species is currently experiencing an increasing population trend. Published 5 December 2008 by the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Mississippi State University Coyote location (Jackson 1951; Young 1951; Berg and Canis latrans (Say, 1823) Chesness 1978; Way 2007). The species is sexually dimorphic, with adult females distinctly CONTEXT AND CONTENT. lighter and smaller than adult males (Kennedy Order Carnivora, suborder Caniformia, et al. 2003; Way 2007). Average head and infraorder Cynoidea, family Canidae, subfamily body lengths are about 1.0–1.5 m with a tail Caninae, tribe Canini. Genus Canis consists length of about Young 1951). The skull of the of six species: C. aureus, C. latrans, C. lupus, coyote (Fig. 2) progresses through 6 distinct C. mesomelas, C. simensis, and C. adustus. developmental stages allowing delineation Canis latrans has 19 recognized subspecies between the age classes of juvenile, immature, (Wilson and Reeder 2005). young, young adult, adult, and old adult (Jackson 1951). -

Population Genomic Analysis of North American Eastern Wolves (Canis Lycaon) Supports Their Conservation Priority Status

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Population Genomic Analysis of North American Eastern Wolves (Canis lycaon) Supports Their Conservation Priority Status Elizabeth Heppenheimer 1,† , Ryan J. Harrigan 2,†, Linda Y. Rutledge 1,3 , Klaus-Peter Koepfli 4,5, Alexandra L. DeCandia 1 , Kristin E. Brzeski 1,6, John F. Benson 7, Tyler Wheeldon 8,9, Brent R. Patterson 8,9, Roland Kays 10, Paul A. Hohenlohe 11 and Bridgett M. von Holdt 1,* 1 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA; [email protected] (E.H.); [email protected] (L.Y.R.); [email protected] (A.L.D); [email protected] (K.E.B.) 2 Center for Tropical Research, Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA; [email protected] 3 Biology Department, Trent University, Peterborough, ON K9L 1Z8, Canada 4 Center for Species Survival, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC 20008, USA; klauspeter.koepfl[email protected] 5 Theodosius Dobzhansky Center for Genome Bioinformatics, Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia 6 School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA 7 School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68583, USA; [email protected] 8 Environmental & Life Sciences, Trent University, Peterborough, ON K9L 0G2, Canada; [email protected] (T.W.); [email protected] (B.R.P.) 9 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Trent University, Peterborough, ON K9L 0G2, Canada 10 North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27601, USA; [email protected] 11 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally. -

Estrategias De Subsistencia De Los Primeros Grupos Humanos Que Poblaron Europa

ESTRATEGIAS DE SUBSISTENCIA DE LOS PRIMEROS GRUPOS HUMANOS QUE POBLARON EUROPA ESTRATEGIAS DE SUBSISTENCIA DE LOS PRIMEROS GRUPOS HUMANOS QUE POBLARON EUROPA: EVIDENCIAS CONSERVADAS EN BARRANCO LEÓN Y FUENTE NUEVA-3 (ORCE) M. PATROCINIO ESPIGARES* RESUMEN Varios yacimientos del Pleistoceno inferior de España, Francia e Italia preservan las evidencias de presencia humana más antiguas de Europa. En este contexto, son particularmente interesantes dos localidades ubicadas en las inmediaciones de la villa de Orce (Cuenca de Baza, Granada), Barranco León (BL) y Fuente Nueva-3 (FN-3), datadas en torno a 1,4 Ma. En estos yacimientos se han identificado evidencias de procesado de cadáveres de grandes mamíferos, realizado con herra- mientas líticas de factura Olduvayense. A estos hallazgos hay que sumarle la presencia de un diente de leche atribuido a Homo sp. en Barranco León. En este trabajo se describen en detalle las marcas de origen antrópico localizadas en estos yacimientos, se analizan los patrones de procesado de los cadáveres, y se discute sobre las estrategias de subsistencia de las primeras comunidades humanas que habitaron Europa. Palabras clave: Marcas de corte, Estrategias de subsistencia, Pleistoceno Inferior, Homo sp. ABSTRACT Several Early Pleistocene sites from Spain, France and Italy preserve ancient evidence of human presence. In this context are particularly interesting two localities placed near the town of Orce (Baza Basin, Granada), Barranco León (BL) and Fuente Nueva-3 (FN-3), dated to ~1.4 Ma. At these sites, evidence of processing of large mammal carcasses produced with Oldowan tools have been recovered. These findings are accompanied by the presence of a deciduous tooth, attributed to Homo sp., in Barranco León. -

Comparative Mito-Genomic Analysis of Different Species of Genus Canis by Using Different Bioinformatics Tools

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 6 Issue 1 Article 4 Comparative Mito-Genomic Analysis of Different Species of Genus Canis by Using Different Bioinformatics Tools Ume Rumman Institute of Natural and Management Sciences (INAM), Rawalpindi, Pakistan, [email protected] Ghulam Sarwar Institute of Zoology, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan, [email protected] Safia Janjua Wright State University, Ohio Fida Muhammad Khan Center for Bioresource Management (CBR), Pakistan Fakhra Nazir Capital University of Science and Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Bioinformatics Commons, Biotechnology Commons, and the Genetics and Genomics Commons Recommended Citation Rumman, U., Sarwar, G., Janjua, S., Khan, F. M., & Nazir, F. (2019). Comparative Mito-Genomic Analysis of Different Species of Genus Canis by Using Different Bioinformatics Tools, Journal of Bioresource Management, 6 (1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.35691/JBM.9102.0102 ISSN: 2309-3854 online This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparative Mito-Genomic Analysis of Different Species of Genus Canis by Using Different Bioinformatics Tools © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. Journal of Bioresource Management does not grant you any other rights in relation to this website or the material on this website. -

Rodentia, Mammalia) in Europe'

Resumen EI yacimiento de Trinchera Oolina es uno de los mas importantes de la Sierra de Atapuerca par su contenido en restos humanos, Homo antecessor en el nivel de Trinchera Dolina 6. Ade mas de esto la enorme riqueza en restos arqueol6gicos y paleontol6gicos hace de Trinchera Dolina un yacimiento unico, de referencia obligada para el Pleistoceno y Paleolitico de Euro pa. Bioestratigraficamente, el yacimiento de Trinchera Oolina (TO) puede dividirse en tres grandes unidades: la que comprende los niveles TD3 a T06; la de los niveles T07 a TOS infe rior y I. de TO 8 superior. T011. Palabras clave: Mamiferos, Pleistoceno. Abstract Gran Dolina is one of the Pleistocene sites located at the Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain). The Gran Dolina deposits belong to different chronological periods of the Early and Middle Pleistocene. The uppermost levels of Gran Dolina (TDII, TDIO and TD8b) contain Middle Pleistocene (post-Cromerian) macro- and micromammal assemblages. The excavation works have overpassed level TDII and have not concluded yet at TDIO: TDII is poor in macromammal remains (carnivores and herbivores) but rich in rodents. The macromammals fossil material from TDtt is very scarce and this enables (for the macromammals) definite conclusions about the chronology and type of community of these levels. The lowermost levels of Gran Dolina (TD3/4, TD5, TD6 and TD8a) contain a different mammal assemblage with typical late Early Pleistocene-Cromerian species. This radical substitution of taxa is placed at TD8 layer probably due to a stratigraphic gap in this level. The level TD6 of the Gran Dolina site contains the earliest fossil human remains of Europe, Homo antecessor, and it has also a rich and diverse micromammal assemblage. -

Large Mammal Biochronology Framework in Europe at Jaramillo: the Epivillafranchian As a Formal Biochron

Quaternary International 389 (2015) 84e89 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Large mammal biochronology framework in Europe at Jaramillo: The Epivillafranchian as a formal biochron Luca Bellucci a, Raffaele Sardella a, Lorenzo Rook b, * a Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, “Sapienza e Universita di Roma”, P.le A. Moro 5, 00185, Roma, Italy b Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita di Firenze, via G. La Pira 4, 50121, Firenze, Italy article info abstract Article history: European large mammal assemblages in the 1.2e0.9 Ma timespan included Villafranchian taxa together Available online 3 December 2014 with newcomers, mostly from Asia, persisting in the Middle Pleistocene. A number of biochronological schemes have been suggested to define these “transitional” faunas. The term Epivillafranchian, originally Keywords: proposed by Bourdier in 1961 and reconsidered as a biochron by Kahlke in the 1990s, is at present widely Biochronology introduced in the literature. This contribution, after selecting the most representative European large Jaramillo mammal assemblages within this chronological interval, provides a new definition proposal for the Epivillafranchian Epivillafranchian as a biochron included within the Praemegaceros verticornis FO/Bison menneri FO, and Late Villafranchian Crocuta crocuta Galerian FO. Europe © 2014 Elsevier Ltd and INQUA. All rights reserved. 1. Historical background communities of this time span primarily include survivors from the latest Villafranchian, as well as more evolved taxa characteristic of The Villafranchian Mammal Age corresponds, in the Interna- the beginning Middle Pleistocene (Kahlke, 2007; Rook and tional Stratigraphic Scale, to a timespan from Late Pliocene to most Martinez Navarro, 2010). -

The Early Hunting Dog from Dmanisi with Comments on the Social

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The early hunting dog from Dmanisi with comments on the social behaviour in Canidae and hominins Saverio Bartolini‑Lucenti1,2*, Joan Madurell‑Malapeira3,4, Bienvenido Martínez‑Navarro5,6,7*, Paul Palmqvist8, David Lordkipanidze9,10 & Lorenzo Rook1 The renowned site of Dmanisi in Georgia, southern Caucasus (ca. 1.8 Ma) yielded the earliest direct evidence of hominin presence out of Africa. In this paper, we report on the frst record of a large‑sized canid from this site, namely dentognathic remains, referable to a young adult individual that displays hypercarnivorous features (e.g., the reduction of the m1 metaconid and entoconid) that allow us to include these specimens in the hypodigm of the late Early Pleistocene species Canis (Xenocyon) lycaonoides. Much fossil evidence suggests that this species was a cooperative pack‑hunter that, unlike other large‑sized canids, was capable of social care toward kin and non‑kin members of its group. This rather derived hypercarnivorous canid, which has an East Asian origin, shows one of its earliest records at Dmanisi in the Caucasus, at the gates of Europe. Interestingly, its dispersal from Asia to Europe and Africa followed a parallel route to that of hominins, but in the opposite direction. Hominins and hunting dogs, both recorded in Dmanisi at the beginning of their dispersal across the Old World, are the only two Early Pleistocene mammal species with proved altruistic behaviour towards their group members, an issue discussed over more than one century in evolutionary biology. Wild dogs are medium- to large-sized canids that possess several hypercarnivorous craniodental features and complex social and predatory behaviours (i.e., social hierarchic groups and pack-hunting of large vertebrate prey typically as large as or larger than themselves).