Artelogie, 16 | 2021 Grete Stern and Gisèle Freund: Two Photographic Modernities in Argentine Exile 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

Cita, Apropiación Y Montaje En La Obra De Grete Stern Paula Bertúa

Paula Bertúa. Poética de la reinvención. (Auto) cita, apropiación y montaje en la obra de Grete Stern. Papeles de Trabajo, Año 4, N° 7, abril 2011, pp. 74-92. Poética de la reinvención. (Auto) cita, apropiación y montaje en la obra de Grete Stern Paula Bertúa (UBA – CONICET) Resumen En este trabajo se analiza una serie de fotomontajes elaborados por la fotógrafa Grete Stern para ilustrar una columna psicológico-sentimental de la revista femenina Idilio. En ellos, Stern retomó, mediante la cita y la apropiación, fotografías ya concebidas, propias y ajenas, para intervenirlas en nuevas composiciones que resignifican sus efectos estéticos, redefiniendo, a su vez, el rol de la práctica artística en un medio de masas. Palabras clave: Fotografía – Cita – Apropiación – Montaje – Grete Stern. Keywords: Photography – Quote – Appropiation – Montage – Grete Stern. Grete Stern en Idilio En agosto de 1948 la fotógrafa Grete Stern comenzaba un trabajo en colaboración de largo aliento que significaría una intervención cultural singular y original en el campo de las publicaciones populares argentinas de mediados de siglo. Convocada por el sociólogo Gino Germani participaría en una columna de consultorio psicológico- sentimental llamada “El psicoanálisis le ayudará” en la revista femenina Idilio, de la Editorial Abril.46 La sección fue el producto de una intervención interdisciplinaria, que 46 Idilio se comenzó a publicar el 26 de octubre de 1948, por la editorial Abril, fundada por Césare Civita. En sus páginas convivían una serie de géneros discursivos habituales en las revistas dirigidas a la mujer: cartas de lectoras, columna de consultorio sentimental, artículos referidos a problemáticas hogareñas, moda y belleza, publicidades e historias de amor, y novelas por entregas. -

VISITOR FIGURES 2015 the Grand Totals: Exhibition and Museum Attendance Numbers Worldwide

SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide VISITOR FIGURES 2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide THE DIRECTORS THE ARTISTS They tell us about their unlikely Six artists on the exhibitions blockbusters and surprise flops that made their careers U. ALLEMANDI & CO. PUBLISHING LTD. EVENTS, POLITICS AND ECONOMICS MONTHLY. EST. 1983, VOL. XXV, NO. 278, APRIL 2016 II THE ART NEWSPAPER SPECIAL REPORT Number 278, April 2016 SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES 2015 Exhibition & museum attendance survey JEFF KOONS is the toast of Paris and Bilbao But Taipei tops our annual attendance survey, with a show of works by the 20th-century artist Chen Cheng-po atisse cut-outs in New attracted more than 9,500 visitors a day to Rio de York, Monet land- Janeiro’s Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil. Despite scapes in Tokyo and Brazil’s economic crisis, the deep-pocketed bank’s Picasso paintings in foundation continued to organise high-profile, free Rio de Janeiro were exhibitions. Works by Kandinsky from the State overshadowed in 2015 Russian Museum in St Petersburg also packed the by attendance at nine punters in Brasilia, Rio, São Paulo and Belo Hori- shows organised by the zonte; more than one million people saw the show National Palace Museum in Taipei. The eclectic on its Brazilian tour. Mgroup of exhibitions topped our annual survey Bernard Arnault’s new Fondation Louis Vuitton despite the fact that the Taiwanese national muse- used its ample resources to organise a loan show um’s total attendance fell slightly during its 90th that any public museum would envy. -

Silver Eye 2018 Auction Catalog

Silver Eye Benefit Auction Guide 18A Contents Welcome 3 Committees & Sponsors 4 Acknowledgments 5 A Note About the Lab 6 Lot Notations 7 Conditions of Sale 8 Auction Lots 10 Glossary 93 Auction Calendar 94 B Cover image: Gregory Halpern, Untitled 1 Welcome Silver Eye 5.19.18 11–2pm Benefit Auction 4808 Penn Ave Pittsburgh, PA AUCTIONEER Welcome to Silver Eye Center for Photography’s 2018 Alison Brand Oehler biennial Auction, one of our largest and most important Director of Concept Art fundraisers. Proceeds from the Auction support Gallery, Pittsburgh exhibitions and artists, and keep our gallery and program admission free. When you place a bid at the Auction, TICKETS: $75 you are helping to create a future for Silver Eye that Admission can be keeps compelling, thoughtful, beautiful, and challenging purchased online: art in our community. silvereye.org/auction2018 The photographs in this catalog represent the most talented, ABSENTEE BIDS generous, and creative artists working in photography today. Available on our website: They have been gathered together over a period of years silvereye.org/auction2018 and represent one of the most exciting exhibitions held on the premises of Silver Eye. As an organization, we are dedicated to the understanding, appreciation, education, and promotion of photography as art. No exhibition allows us to share the breadth and depth of our program as well as the Auction Preview Exhibition. We are profoundly grateful to those who believe in us and support what we bring to the field of photography. Silver Eye is generously supported by the Allegheny Regional Asset District, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, The Heinz Endowments, The Pittsburgh Foundation, The Fine Foundation, The Jack Buncher Foundation, The Joy of Giving Something Foundation, The Hillman Foundation, an anonymous donor, other foundations, and our members. -

Beets Documentation Release 1.5.1

beets Documentation Release 1.5.1 Adrian Sampson Oct 01, 2021 Contents 1 Contents 3 1.1 Guides..................................................3 1.2 Reference................................................. 14 1.3 Plugins.................................................. 44 1.4 FAQ.................................................... 120 1.5 Contributing............................................... 125 1.6 For Developers.............................................. 130 1.7 Changelog................................................ 145 Index 213 i ii beets Documentation, Release 1.5.1 Welcome to the documentation for beets, the media library management system for obsessive music geeks. If you’re new to beets, begin with the Getting Started guide. That guide walks you through installing beets, setting it up how you like it, and starting to build your music library. Then you can get a more detailed look at beets’ features in the Command-Line Interface and Configuration references. You might also be interested in exploring the plugins. If you still need help, your can drop by the #beets IRC channel on Libera.Chat, drop by the discussion board, send email to the mailing list, or file a bug in the issue tracker. Please let us know where you think this documentation can be improved. Contents 1 beets Documentation, Release 1.5.1 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Contents 1.1 Guides This section contains a couple of walkthroughs that will help you get familiar with beets. If you’re new to beets, you’ll want to begin with the Getting Started guide. 1.1.1 Getting Started Welcome to beets! This guide will help you begin using it to make your music collection better. Installing You will need Python. Beets works on Python 3.6 or later. • macOS 11 (Big Sur) includes Python 3.8 out of the box. -

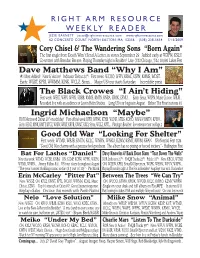

Right Arm Resource 090715.Pmd

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE WEEKLY READER JESSE BARNETT [email protected] www.rightarmresource.com 62 CONCERTO COURT, NORTH EASTON, MA 02356 (508) 238-5654 7/15/2009 Cory Chisel & The Wandering Sons “Born Again” The first single from Death Won’t Send A Letter, in stores September 29 Added early at WXPN, KSLU Co-written with Brendan Benson Playing Thursday night in Boulder! Live: 7/22 Chicago, 7/24 10,000 Lakes Fest Dave Matthews Band “Why I Am” #1 Most Added! New & Active! Indicator Debut 24*! First week: WCOO, WFIV, KBAC, KSPN, KMMS, WDST... Early: WXRT, KPRI, WWMM, KINK, WCLZ, Sirius... Major US tour starts Saturday Incredible press The Black Crowes “I Ain’t Hiding” First week: WEXT, WFIV, WFPK, KDBB, KMMS, KMTN, KNBA, KROK, KFMU... Early: Sirius, WXPN, Music Choice, WBJB... Recorded live with an audience at Levon Helm Studios Long US tour begins in August Before The Frost in stores 9/1 Ingrid Michaelson “Maybe” R&R Monitored Debut 20* on add day! First official week: KPRI, WRNX, KTHX, WCNR, KTBG, KOHO, WMWV, KMTN, KFMU... Early: KENZ, KINK, KMTT, KTCZ, WXRV, WRLT, KRVB, KWMT, KXLY, Sirius, WCLZ, KPTL... Playing in Boulder! See extensive tour on Page 2 Good Old War “Looking For Shelter” First week: WTMD, WBJB, KMTN, KCLC, WNRN, WNKU, KZMV, KSMT, KRVM, KFAN XPoNential Fest 7/24 “Good Old War charms with a genuine feel-goodness. The album has no posing or forced trickery.” - Huffington Post Bat For Lashes “Daniel” Davy Knowles & Back Door Slam “Tear Down The Walls” New this week: WTMD, WCBE, KNBA ON: KCMP, KCRW, WFPK, WXPN, R&R Indicator 21*! FMQB Tracks 22*! Public 18*! New: KBCO, WTMD WYMS, WNRN.. -

OSA-AMP-2009-06.Pdf

T H E S T U 0' "e ,N T 0 P I N I 0 N P U B L I C A T I 0 N Spirit ~\..SO INs~, ()~ 116ter!JoiJrd£ ' ll/p- I t s not 0 Camp., ~ c. _ nearly .. -s .t.un as . as p Jt sounds . ages 12 &13 Students impact campus/ pages 4, 5, 7, 10 U7D in Perspective UT Systems student regent looks . back on hl S time at UTD Pages 8 &9 • $ U M M E R. 2 0 0.9 • , V .0 J.., U M :e , .5 -.. , .•... .. I S S U, E • • 8 , ' •. A .M .P• •• U ;r, 0 . A .I.. L .A .s. E. 0 U , • • , , • • • • • , 2 THE EDITORS DESK < < < < < <', ~ •• " hhaha is ste~ng au tn~ at- ', ' 1' al~trated than all the:C~t)l~1ic )?r<?. .. · : ', ·: • · .. ~ :; m what is·othefWiSe a :gJ:.~~tJSS\!~· ' : n;nd·J'n\'willing .. tention ~.ro . l dU kAMPhas ever run,.... · Th.iS'is one thebest arttcles: . n. they want if it appeaM in the .t.. :int whatever ,offenstve JlOt;lSense.. ,. -,.C. • t ; to let wem pr . Even the artWork ts mag~cen . d sari'te issue· as -stuff1ike , t\\J~. , . ·a.": ' ·ariicleswere-thoughtful,un · v , Saras an .n.arons ·.t. I also thought;n.enn.ys~ ·· 1 • ::td neverblwecomeup\Wl~u .1 . L h~-nrovoking. 1 wow. more irtlportanuy, I.U.Oug > 1'• ' , ' all ood' . • • some of those ~~ents, but ~ey ~e t: ~·tha~ AMP:for:a great issue~ th ks Art, for a great story, . Anyway, · a.n · • · · •1-u"'"rs·ge· t the spotlight. -

Argentinian Photography During the Military Dictatorship (1976-1983)

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 A Light in the Darkness: Argentinian Photography During the Military Dictatorship (1976-1983) Ana Tallone Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1152 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A LIGHT IN THE DARKNESS: ARGENTINIAN PHOTOGRAPHY DURING THE MILITARY DICTATORSHIP (1976-1983) by Ana Tallone A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 © 2015 Ana Tallone All Rights Reserved ! ii! This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Katherine Manthorne _____________________ ______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Rachel Kousser ______________________ ______________________________ Date Executive Officer Geoffrey Batchen Anna Indych-López Jordana Mendelson Supervisory Committee ! iii! ABSTRACT A Light in the Darkness: Argentinian Photography During the Military Dictatorship (1976-1983) by Ana Tallone Adviser: Katherine Manthorne In 2006, on the thirtieth anniversary of the military coup that brought Argentinian democracy to a halt, a group of photojournalists put together an outstanding exhibition of images from the dictatorship.1 This dissertation critically engages with the most enduring photojournalistic works produced during this period and featured in the landmark retrospective. -

MALBA COLLECTION Agustín Pérez Rubio OPEN HISTORY, MULTIPLE TIME

MALBA COLLECTION Agustín Pérez Rubio OPEN HISTORY, MULTIPLE TIME. A NEW TURN ON THE MALBA COLLECTION 33 …we never had grammars, nor collections of old plants. And we never knew what images selected and settled on according to the criteria of those who urban, suburban, frontier and continental were. articulate “authorized” discourses on art. Even today, we unwittingly find Oswald de Andrade1 ourselves exercising power in a practice that continues to be enmeshed in that state of afairs. The historian “stains” history just as, in Lacan’s theory …forget the stuf of the Old World, and put all of our hope, and our efort, into creating of vision, the viewer stains the scopic field.4 And that is made manifest if this new culture right here. Forget artists and schools; forget that literature and philosophy; the field of action is that artifice called Latin America. While it is true that the be cleansed and renewed; think to the beat of this life that surrounds us ... Leave behind, region is held together by certain common traits, its complex cultural reality then, authors and teachers that are no longer of any use to us; they have nothing to tell us about what we must discover in ourselves. has been shaped entirely on the basis of a colonial logic driven by political Joaquín Torres García2 and economic powers. In this globalized age, we cannot situate ourselves on a tabula rasa from which to look back at history and Latin American art as if nothing had happened before. …visual artifacts refuse to be confined by the interpretations placed on them in the present. -

Discours Et Document

I Schedae Prépublications de l’Université de Caen Basse-Normandie Fascicule n° 1 2006 Colloque International Discours et Document International Symposium Discourse and Document Presses universitaires de Caen II III Schedae, 2006 Fascicule n° 1 Colloque International : Discours et Document International Symposium: Discourse and Document Responsable : Patrice ENJALBERT L’objectif du colloque Discours et Document est de rassembler des chercheurs intéres- sés par ce qu'on peut appeler le « niveau document » en linguistique du discours, en TAL ou en ingénierie documentaire. Ce fascicule regroupe les communications pré- sentées au colloque. Présidents du colloque M.-P. PÉRY-WOODLEY, U. Toulouse 2 ; P. E NJALBERT, U. Caen ; M. GAIO, U. Pau et Pays de l’Adour. Comité de programme J. BATEMAN, U. Bremen, Allemagne ; D. BATTISTELLI, U. Paris 4, France ; Y. BESTGEN, U. C. Lou- vain, Belgique ; B. BOGURAEV, IBM T.J. Watson Research Center, USA ; A. BORILLO, U. Tou- louse 2, France ; N. BOUAYAD-AGHA, U. Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Espagne ; F. CERBAH, Dassault Aviation, France ; M. CHAROLLES, U. Paris 3, France ; D. CRISTEA, U. Iasi, Romania ; L. DEGAND, U. C. Louvain, Belgique ; D. DUTOIT, Sté Memodata, France ; P. ENJALBERT, U. Caen, France ; S. FERRARI, U. Caen, France ; O. FERRET, CEA, France ; M. GAIO, U. Pau, France ; B. GRAU, U. Paris-Sud, France ; N. HERNANDEZ, U. Caen, France ; G. LAPALME, U. Montréal, Québec, Canada ; A. LE DRAOULEC, U. Toulouse 2, France ; A. LEHMAM, Sté Pertinence Mining.com, France ; D. LEGALLOIS, U. Caen, France ; N. LUCAS, U. Caen et CNRS, France ; F. M AUREL, U. Caen, France ; A. MAX, U. Paris-Sud, France ; J.-L. -

Short Article from Hands That Talk

Hands that Talk, Eyes that Listen By Lou Gemunden Spitta Figure 1. Ellen Auerbach and Grete Stern, Petrole Hahn, 1931, Berlin. Grete Stern’s Petrole Hahn does more than establish a new way of seeing; it also creates new ways of thinking. The mannequin’s head marks the center of the image spatially; it is also the site of the advertisement’s explicit message: Pétrole Hahn oil leads to clean, bright, and elegantly wavy hair. Stern’s composition of the image owes a great deal to two influential figures in her career, Walter Peterhans and Ellen Auerbach. Stern learned about the importance of technical precision and how to “see photographically”1 from Peterhans; she later experimented with these techniques in collaboration with Auerbach, a fellow student of Peterhans’ private class. Stern, Peterhans, and Auerbach met in Berlin in the late 1920s, after Stern had decided to leave her hometown of Wuppertal to pursue a career in photography. With the help of her brother, who worked in the film industry, Stern became Peterhans’ only photography student for over a year, 1 Translated by the author from Walter Peterhans’ notion “ver fotográficamente.” until Auerbach’s arrival in 1928.2 Although numerous publications have credited Stern with Petrole Hahn, the image was originally a collaborative work between the two female photographers.3 The composition of the image, a single figure in front of a simple background, directs the viewer’s eyes from the hair to the hair product. The photograph’s exact focus on the hair, and on the bright and shiny bottle of hair oil, gives the viewer a central starting point to begin reading the image—namely the hair—and a second focal point—the hair product—so that viewer’s eyes shift from one point to the next. -

Poteli MAY 2 9 1986

PASSION IN SCIENCE AND ROCK MUSIC: A Comparison of Two Faiths by Ebon Fisher Bachelor of Fine Arts Carnegie-Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 1982 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN VISUAL STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE, 1986 @ Ebon Fisher The Author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part Signature of the author _____ Fisher Ebon Fisher Department of Architecture May 16,1986 Certified by Otto Piene Professor of Visual Design Thesis Supervisor Accepted by. Nicholas Negroponte Chairman Departmental Committee on Graduate Students MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY poteli MAY 2 9 1986 LIBRARIES Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLIbMIries Email: [email protected] Document Services http:i/libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. The images contained in this document are of the best quality available. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS A b stract ...................................................................... 4 Introduction ...................................................................... 5 Chapter