The Changing Role of the Planner. Implications of Creative Pragmatism in Estonian Spatial Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

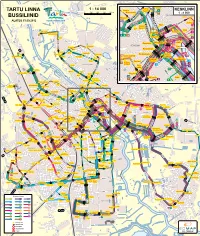

Tartu Linna Bussiliinid

E E E 21 Raadi E Raadi E r 4 P e E o pk so u m 3 i r 9 ur ie M s u t N ee RAADI-KRUUSAMÄE t Aiandi n m v Pärna a akraa v e koguj Nurme r õõbus V E a N Risti a Jänese rn E ä E P Orava Risti E E Peetri St EE aa kirik E di E Peetri kirik M on A i Peetri kirik Narvamäe JÕ Tartu Näitused Laululava G I Narvamäe E a n E Piiri u E Sa Kasarmu 8 Maaülikool P Vene ui E E e E Palmi- Mur s E i E s 1 : 14 000 E oo pk t E Herne KESKLIeNN E SUPILINN r Tuglase E hoone 4 E e TARTU LINNA 0 250 500 750 1 000 m E a E Kroonuaia i E a 7 1 : 8 000 Tuglase E F Kreutzwaldi u E E .R ÜLEJÕE E .K n E Puiestee Kreutzwaldi r o N 13 JAAMAMÕISA BUSSILIINID eu Kloostri o EEE E tzw r a a E K r E ALATES 03.09.2012 ld 16A E v t i E se s e a u p ii V at Jaama E i a H Hurda E a a m a E L Kivi R j E E Hurda b 18 h Palmi- n E Hiie Ta õ BeE tooni a TÄHTVERE a t E E r hoone E J P E d a Lai 7 E E 16 Paju aa 10 Hiie ps u E Pikk m E E E a Sõpruse pst. -

Soviet Housing Construction in Tartu: the Era of Mass Construction (1960 - 1991)

University of Tartu Faculty of Science and Technology Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences Department of Geography Master thesis in human geography Soviet Housing Construction in Tartu: The Era of Mass Construction (1960 - 1991) Sille Sommer Supervisors: Michael Gentile, PhD Kadri Leetmaa, PhD Kaitsmisele lubatud: Juhendaja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Juhendaja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Osakonna juhataja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Tartu 2012 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Literature review ................................................................................................................................. 5 Housing development in the socialist states .................................................................................... 5 From World War I until the 1950s .............................................................................................. 5 From the 1950s until the collapse of the Soviet Union ............................................................... 6 Socio-economic differentiations in the socialist residential areas ................................................... 8 Different types of housing ......................................................................................................... 11 The housing estates in the socialist city .................................................................................... 13 Industrial control and priority sectors .......................................................................................... -

Tallinna Kaubamaja Grupp As

TALLINNA KAUBAMAJA GRUPP AS Consolidated Interim Report for the Fourth quarter and 12 months of 2016 (unaudited) Tallinna Kaubamaja Grupp AS Table of contents MANAGEMENT REPORT ............................................................................................................................................ 4 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ........................................................................................................... 12 MANAGEMENT BOARD’S CONFIRMATION TO THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ....... 12 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION ....................................................................... 13 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF PROFIT OR LOSS AND OTHER COMPREHENSIVE INCOME ........ 14 CONSOLIDATED CASH FLOW STATEMENT ............................................................................................. 15 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN OWNERS’ EQUITY ...................................................... 16 NOTES TO THE CONSOLIDATED INTERIM ACCOUNTS ......................................................................... 17 Note 1. Accounting Principles Followed upon Preparation of the Consolidated Interim Accounts ........ 17 Note 2. Cash and cash equivalents ............................................................................................................... 18 Note 3. Trade and other receivables .............................................................................................................. 18 Note 4. Trade receivables .............................................................................................................................. -

1 Estonian University of Life Sciences Kreutzwaldi 1

ESTONIAN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE COURSE (ESTILC) 2018/2019 ORGANISING INSTITUTION ’S INFORMATION FORM NAME OF THE INSTITUTION : ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES ADDRESS : KREUTZWALDI 1, TARTU COUNTRY : ESTONIA ESTILC LANGUAGE LEVEL COURSES ORGANISED: LEVEL I (BEGINNER ) X LEVEL II (INTERMEDIATE ) NUMBER OF COURSES : 1 NUMBER OF COURSES : DATES : 08.08-24.08.2018 DATES : WEB SITE HTTPS :// WWW .EMU .EE /EN /ADMISSION S/EXCHANGE -STUDIES /ERASMUS / PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL STUDENT APPLICATIONS FOR OUR ESTILC COURSE SHOULD BE SENT BY E -MAIL TO THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS : APPLICATION DEADLINE 31.05.2018 STAFF JOB TITLE / NAME ADDRESS , TELEPHONE , FAX , E-MAIL CONTACT PERSON ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES FOR ESTILC KREUTZWALDI 56/1, 51014 TARTU /E STONIA LIISI VESKE PHONE : +372 731 3174 JOB TITLE FAX : +372 731 3037 PROGRAMME COORDINATOR E-MAIL : LIISI .V ESKE @EMU .EE ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES KREUTZWALDI 56/1, 51014 TARTU /E STONIA RESPONSIBLE PERSON FOR THE PROGRAMME PHONE : +372 731 3174 FAX : +372 731 3037 LIISI VESKE E-MAIL : LIISI .V ESKE @EMU .EE PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION • DESCRIPTION OF TOWN - SHORT HISTORY AND LOCATION 1 Tartu is the second largest city of Estonia. Tartu is located 185 kilometres to south from the capital Tallinn. Tartu is known also as the centre of Southern Estonia. The Emajõgi River, which connects the two largest lakes (Võrtsjärv and Peipsi) of Estonia, flows for the length of 10 kilometres within the city limits and adds colour to the city. As Tartu has been under control of various rulers throughout its history, there are various names for the city in different languages. -

Urban Trees As Social Triggers: the Case of the Ginkgo Biloba Specimen in Tallinn, Estonia

234 Riin Magnus, Heldur Sander Sign Systems Studies 47(1/2), 2019, 234–256 Urban trees as social triggers: The case of the Ginkgo biloba specimen in Tallinn, Estonia Riin Magnus Department of Semiotics University of Tartu Jakobi 2, 51005 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] Heldur Sander Mahtra 9–121 20038 Tallinn, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Urban trees are considered to be essential and integral to urban environ- ments, to contribute to the biodiversity of cities as well as to the well-being of their inhabitants. In addition, urban trees may also serve as living memorials, helping to remember major social eruptions and to cement continuity with the past, but also as social disruptors that can induce clashes between different ideals of culture. In this paper, we focus on a specific case, a Ginkgo biloba specimen growing at Süda Street in the centre of Tallinn, in order to demonstrate how the shifts in the meaning attributed to a non-human organism can shape cultural memory and underlie social confrontations. Integrating an ecosemiotic approach to human-non-human interactions with Juri Lotman’s approach to cultural memory and cultural space, we point out how non-human organisms can delimit cultural space at different times and how the ideal of culture is shaped by different ways of incorporating or other species in the human cultural ideal or excluding them from it. Keywords: urban greenery; cultural memory; human-plant interactions; Ginkgo biloba; cultural space Riin Magnus, Heldur Sander In the environmental humanities’ endeavour to highlight the role of other species in the shaping of human culture and environments, animals have played the lead role for a long time. -

DTZ Research

Property Times Baltic Retail H2 2012 New projects in the pipeline 8 February 2013 Consumer confidence strengthened and household consumption expanded during 2012. The turnover of retail trade is expected to continue its growth also in 2013. Contents Macro-economic trends in Baltics 2 Most of the development projects completed in 2012 were medium-scale Retail Market in Estonia 4 (mainly hyper- and supermarkets); several large-scale retail projects are in the pipeline for the upcoming years, but only a few of them have the construction Retail Market in Latvia 8 process already initiated. Retail Market in Lithuania 12 Vacancy rate is close to 0% in the shopping centres with successful Author management. However, shopping centres with ineffective organisation or less favourable locations still struggle over their occupancy rates. Aivar Tomson Baltic Head of Research Improving retail trade turnover and increased occupancy has upward pressure + 372 6 264 250 on rents in prime shopping schemes. There are no notable rental rate changes [email protected] in secondary cities and secondary locations in capital cities. Cont acts The retail investment market saw an increased interest from foreign property investors. Several investment transactions in retail segment were in process in Magali Marton 2012, with two of them being closed by the end of the year ( Gedimino 9 SC in Head of CEMEA Research Vilnius and Mustika SC in Tallinn). Retail investment prospects for 2013 are + 33 (0)1 49 64 49 54 also promising. [email protected] Figure 1 Retail confidence index Hans Vrensen Global Head of Research + 44 (0)20 3296 2159 [email protected] Source: National Statistics, Estonian Institute of Economic Research DTZ Research Baltic Retail H2 2012 Macroeconomic Trends in the Baltic States Annual inflation meanwhile has reached its historical minimum ever since autumn 2010, and averaged at about Estonia 1.6% at the end of 2012, coming primarily from globally Estonian economy is in quite a good health, with evident increase in fuel and food prices. -

Mitte-Tartutu

MitteMitte-Tarttuu Mitte-Tartu Mitte-Tartu TOPOFON Koostanud ja toimetanud Sven Vabar Kujundanud Mari Ainso Pildistanud Kaja Pae Mitte-Tartu tänab: Eesti Kultuurkapitali, Tartu Kultuurkapitali, kirjandusfestivali Prima Vista ja Eesti Kirjanike Liidu Tartu osakonda © Autorid Topofon, 2012 Tartu ISBN 978-9949-30-404-2 Trükkinud AS Ecoprint Sisukord Sven Vabar Eessõna 6 Anti Saar Ernst 16 Berk Vaher Baltijos Cirkas 28 Joanna Ellmann maa-alused väljad 38 Maarja Pärtna 48 Kaja Pae 10π 58 Aare Pilv Servad 74 Tanel Rander Odessa või São Paulo? 90 Meelis Friedenthal Kass 100 Lauri Pilter Rälby ja Tarby 114 c: Teekond põllule 132 Erkki Luuk NÕIUTUD X 142 Tanel Rander Jõgi ja jõerahvas 156 Kiwa t-st 168 Mehis Heinsaar Kuusteist vaikuse aastat 190 Sven Vabar Tartu kaks lagendikku 200 Sven Vabar Tänavakunstnikud 212 Jaak Tomberg Faddei Bulgarini kümme soont 234 andreas w blade runner : jooksja mõõgateral 288 Mehis Heinsaar Ta on valmis ja ootel 302 5 Sven Vabar Eessõna Werneri kohvik, kevad/sügis-hooajaline Toomemägi, kirjanduslik Kar- lova, Supilinn oma aguliromantikaga. Neist kohtadest käesolevas raa- matus juttu ei tule. See kõik on Tartu. Mitte-Tartu on mujal. Hiinalinn oma hämara, postmilitaristliku elanikkonnaga ja määratu garaaživo- hanguga sealsamas kõrval. Raadi lennuväli. Annelinn. Aardla-kandi tühermaad ja Võru maantee äärsed põllupealsed uusarendused. Luhad. Ühe Turu tänava autopesula külge ehitatud igavikuline hamburgeri- putka, kus on tunda Jumala ligiolekut. Küütri tänava metroopeatus. Emajõgi küll, aga pigem jõepõhja muda ühes kõige seal leiduvaga. Supilinn küll, aga üks hoopis teistsugune Supilinn. Tõsi, piir Tartu ja Mitte-Tartu vahel on kohati hämar ja hägune nagu Mitte-Tartu isegi. Humanitaarteadustes tähistab „mitte-koht“ tavaliselt prantsuse antropoloogi Marc Augé poolt kasutusele võetud terminit. -

Gentrification in a Post-Socialist Town: the Case of the Supilinn District, Tartu, Estonia

GENTRIFICATION IN A POST-SOCIALIST TOWN: THE CASE OF THE SUPILINN DISTRICT, TARTU, ESTONIA Nele NUTT Mart HIOB Sulev NURME Sirle SALMISTU Abstract This article deals with the changes that Nele NUTT (corresponding author) have taken place in the Supilinn district in Tartu, Estonia due to the gentrification process. The Lecturer, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tallinn gentrification process affects the cultural, social, University of Technology, Tartu College, Estonia economic, and physical environment of the area. Tel.: 0037-2-501.4767 People have been interested in this topic since E-mail: [email protected] the 1960s. Nowadays, there is also reason to discuss this issue in the context of Estonia and Mart HIOB of the Supilinn district. Studying and understand- Lecturer, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tallinn ing the processes that take place in the living University of Technology, Tartu College, Estonia environment, provides an opportunity to be more aware about them and to influence the develop- Sulev NURME ment of these processes. This article provides Lecturer, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tallinn an analysis of the conditions necessary for gen- trification in the Supilinn district, describes the University of Technology, Tartu College, Estonia process of gentrification, and tries to assess the current developmental stage of the gentrification Sirle SALMISTU process. Lecturer, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tallinn Cities are shaped by their people. Every area University of Technology, Tartu College, Estonia has a unique look that is shaped not only by the physical environment, but also by the principles, values, and wishes of its residents. Local resi- dents influence the image of the mental and the physical space of the area. -

Programme Handbook 1

Tartu, Estonia 8 - 10 August 2017 Programme handbook 1 Contents Programme ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Abstracts ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Invited speakers .................................................................................................................................. 6 Participants ....................................................................................................................................... 17 Practical information ............................................................................................................................ 38 Directions .............................................................................................................................................. 44 Contacts of local organizers .................................................................................................................. 46 Maps of Tartu ........................................................................................................................................ 47 Programme Monday, August 7th 16:00 – 20:00 Registration of participants Estonian Biocentre, Riia 23b 20:00 – 22:00 Welcome reception & BBQ Vilde Ja Vine restaurant, Vallikraavi 4 Tuesday, August 8th 08:45 – 09:35 Registration of participants Estonian Biocentre, Riia 23b 9:35 -

Vastandumised / Confrontations 19.06.-25.07.2010 Vastandumised / Confrontations Vastandumised

EKL 10. AASTANÄITUS / 10TH ANNUAL EXHIBITION OF ESTONIAN ARTISTS’ ASSOCIATION VASTANDUMISED / CONFRONTATIONS 19.06.-25.07.2010 VASTANDUMISED / CONFRONTATIONS VASTANDUMISED Koostaja-toimetaja / Compiled and edited by Elin Kard Tõlge / Translation: Elin Kard, Maris Karjatse Tõlke toimetaja / Proof-reading: Maris Karjatse Fotod / Photos: Stanislav Stepashko Kujundus / Graphic design by Maris Lindoja Trükk / Printed by Printon Kaanel / On the cover: Evi Tihemets PURSE / ERUPTION Söövitus, kuivnõel / Etching, drypoint 2010 Väljaandja Eesti Kunstnike Liit / Published by Estonian Artists’ Association © autorid / authors Kataloogi väljaandmist on toetanud Eesti Kultuurkapital The publication of the catalogue was supported by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia ISBN: 9789949215799 © Eesti Kunstnike Liit / Estonian Artists’ Association, 2010 EKL 10. AASTANÄITUS / 10TH ANNUAL EXHIBITION OF ESTONIAN ARTISTS’ ASSOCIATION VASTANDUMISED / CONFRONTATIONS 19.06.-25.07.2010 TALLINNA KUNSTIHOONE / TALLINN ART HALL KURAATOR / CURATED BY ENN PÕLDROOS KUJUNDUS / DESIGN BY JAAN ELKEN EESTI KUNSTNIKE LIIDU AASTANÄITUSED 2000-2010 2000 MEHITAMINE / MANNING Kuraatorid ja kujundus / Curated and design by DÉJA VU EHK EESTI KUNSTI LÜHIAJALUGU / Jaak Soans, Hanno Soans DÉJA VU OR SHORT HISTORY OF ESTONIAN ART Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Tallinn / Kuraator / Curated by Toomas Vint The Museum of Estonian Architecture, Tallinn Kujundus / Design by Aili Vint Tallinna Kunstihoone / Tallinn Art Hall KOHASPETSIIFILISED INSTALLATSIOONID JA AKTSIOONID TALLINNA LINNARUUMIS / AIDS -

Sõprade Sõit” on Tartu Linna Ja Linnaümbruse Kergliiklusteedel Toimuv Ühine Spordisõit Valitud Tempogruppides, Kas 32Km Või 54Km Pikkusel Rajal

II SOPRADE~ SOIT~ 1.OKTOOBER2017 32KM/54KM RULLSUUSKADE JA UISKUDEGA ~ .. - - , TOUKE- JA JALGRATASTEGA UMBER TERVE TARTU www.SuusaAkadeemia.ee MIS ON SOPRADE~ SOIT~ “II Terve Tartu Sõprade Sõit” on Tartu linna ja linnaümbruse kergliiklusteedel toimuv ühine spordisõit valitud tempogruppides, kas 32km või 54km pikkusel rajal. Osaleda võib rullsuuskade-, rulluiskude-, tõukeratta- või jalgrattaga. Ühisstart sõidule on 1.oktoobril 2017 kell 11:00 Tartu kesklinnas. Tegemist ei ole võistlusega, vaid ühissõiduga, kuid osalejad saavad teada oma distantsi läbimise aja. Raja pikkus on valikuliselt, kas 32km või 54km ning valida saab järgnevate tempogruppide vahel: 32KM TEMPO SOOVITUSLIKULT Rahulik ~10km/h rullsuusk Mõõdukas ~12km/h rullsuusk, -uisk, (tõuke)ratas 54KM Rahulik ~12km/h rullsuusk, tõukeratas Mõõdukas ~15km/h rullsuusk, -uisk, (tõuke)ratas Kiire ~20-25km/h rulluisk ja jalgratas II SOPRADE~ SOIT~ www.SuusaAkadeemia.ee RADA 32KM/54KM II VAHI 14km START ja FINIŠ: KÜÜNI TÄNAV III I LOUNAKAS IHASTE 14km IV 14km ROPKA 12km KM I IHASTE RING 14km: KESKLINN - ANNELINN - LOHKVA - IHASTE - A.LE COQ SPORT 54 II VAHI 14km ANNE KANAL - ROOSI - ERM - VAHI - KVISSENTALI - TÜ SPORDIHALL III LÕUNAKESKUS 14km: SUPILINN - TOOMEMÄGI- LÕUNAKESKUS - RAUDTEE - TAMME STAADION IV ROPKA 12km: RAUDTEE - RINGTEE - VANGLA - SIILI - SÕPRUSE - ANNE KANAL - FINIŠ KM I IHASTE RING 14km: KESKLINN - ANNELINN - LOHKVA - IHASTE - A.LE COQ SPORT 32 II VAHI 14km ANNE KANAL - ROOSI - ERM - VAHI - KVISSENTALI - TÜ SPORDIHALL III LÕUNAKESKUS 4km: SUPILINN - JAKOBI MÄGI - FINIŠ www.SuusaAkadeemia.ee OSALEJALE PARKIMINE Kasutada turuhoone, Vabaduse tn, Poe tn, Tartu Kaubamaja, Ülikooli tn parkimisalasid START JA PAKIHOID Start “II Terve Tartu Sõprade Sõidule” on 1.oktoobril 2017 kell 11:00. -

![Urban Energy Planning in Tartu [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu] Große, Juliane; Groth, Niels Boje; Fertner, Christian; Tamm, Jaanus; Alev, Kaspar](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3273/urban-energy-planning-in-tartu-pleec-report-d4-2-tartu-gro%C3%9Fe-juliane-groth-niels-boje-fertner-christian-tamm-jaanus-alev-kaspar-1533273.webp)

Urban Energy Planning in Tartu [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu] Große, Juliane; Groth, Niels Boje; Fertner, Christian; Tamm, Jaanus; Alev, Kaspar

Urban energy planning in Tartu [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu] Große, Juliane; Groth, Niels Boje; Fertner, Christian; Tamm, Jaanus; Alev, Kaspar Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Große, J., Groth, N. B., Fertner, C., Tamm, J., & Alev, K. (2015). Urban energy planning in Tartu: [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu]. EU-FP7 project PLEEC. http://pleecproject.eu/results/documents/viewdownload/131-work- package-4/579-d4-2-urban-energy-planning-in-tartu.html Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Deliverable 4.2 / Tartu Urban energy planning in Tartu 20 January 2015 Juliane Große (UCPH) Niels Boje Groth (UCPH) Christian Fertner (UCPH) Jaanus Tamm (City of Tartu) Kaspar Alev (City of Tartu) Abstract Main aim of report The purpose of Deliverable 4.2 is to give an overview of urban en‐ ergy planning in the 6 PLEEC partner cities. The 6 reports il‐ lustrate how cities deal with dif‐ ferent challenges of the urban energy transformation from a structural perspective including issues of urban governance and spatial planning. The 6 reports will provide input for the follow‐ WP4 location in PLEEC project ing cross‐thematic report (D4.3). Target group The main addressee is the WP4‐team (universities and cities) who will work on the cross‐ thematic report (D4.3). The reports will also support a learning process between the cities. Further, they are relevant for a wider group of PLEEC partners to discuss the relationship between the three pillars (technology, structure, behaviour) in each of the cities. Main findings/conclusions The Estonian planning system allots the main responsibilities for planning activities to the local level, whereas the regional level (county) is rather weak.