Overkill: the Rise of Paramilitary Police Raids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

Examining Police Militarization

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2021 Citizens, Suspects, and Enemies: Examining Police Militarization Milton C. Regan Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2346 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3772930 Texas National Security Review, Winter 2020/2021. This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Law and Race Commons, Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Citizens, Suspects, and Enemies: Examining Police Militarization Mitt Regan Abstract Concern about the increasing militarization of police has grown in recent years. Much of this concern focuses on the material aspects of militarization: the greater use of military equipment and tactics by police officers. While this development deserves attention, a subtler form of militarization operates on the cultural level. Here, police adopt an adversarial stance toward minority communities, whose members are regarded as presumptive objects of suspicion. The combination of material and cultural militarization in turn has a potential symbolic dimension. It can communicate that members of minority communities are threats to society, just as military enemies are threats to the United States. This conception of racial and ethnic minorities treats them as outside the social contract rather than as fellow citizens. It also conceives of the role of police and the military as comparable, thus blurring in a disturbing way the distinction between law enforcement and national security operations. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Islamophobia Monitoring Month: December 2020

ORGANIZATION OF ISLAMIC COOPERATION Political Affairs Department Islamophobia Observatory Islamophobia Monitoring Month: December 2020 OIC Islamophobia Observatory Issue: December 2020 Islamophobia Status (DEC 20) Manifestation Positive Developments 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Asia Australia Europe International North America Organizations Manifestations Per Type/Continent (DEC 20) 9 8 7 Count of Discrimination 6 Count of Verbal & Physical Assault 5 Count of Hate Speech Count of Online Hate 4 Count of Hijab Incidents 3 Count of Mosque Incidents 2 Count of Policy Related 1 0 Asia Australia Europe North America 1 MANIFESTATION (DEC 20) Count of Discrimination 20% Count of Policy Related 44% Count of Verbal & Physical Assault 10% Count of Hate Speech 3% Count of Online Hate Count of Mosque Count of Hijab 7% Incidents Incidents 13% 3% Count of Positive Development on Count of Positive POSITIVE DEVELOPMENT Inter-Faiths Development on (DEC 20) 6% Hijab 3% Count of Public Policy 27% Count of Counter- balances on Far- Rights 27% Count of Police Arrests 10% Count of Positive Count of Court Views on Islam Decisions and Trials 10% 17% 2 MANIFESTATIONS OF ISLAMOPHOBIA NORTH AMERICA IsP140001-USA: New FBI Hate Crimes Report Spurs U.S. Muslims, Jews to Press for NO HATE Act Passage — On November 16, the USA’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), released its annual report on hate crime statistics for 2019. According to the Muslim-Jewish Advisory Council (MJAC), the report grossly underestimated the number of hate crimes, as participation by local law enforcement agencies in the FBI's hate crime data collection system was not mandatory. -

Presidential Documents Vol

42215 Federal Register Presidential Documents Vol. 81, No. 125 Wednesday, June 29, 2016 Title 3— Proclamation 9465 of June 24, 2016 The President Establishment of the Stonewall National Monument By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation Christopher Park, a historic community park located immediately across the street from the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City (City), is a place for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community to assemble for marches and parades, expres- sions of grief and anger, and celebrations of victory and joy. It played a key role in the events often referred to as the Stonewall Uprising or Rebellion, and has served as an important site for the LGBT community both before and after those events. As one of the only public open spaces serving Greenwich Village west of 6th Avenue, Christopher Park has long been central to the life of the neighborhood and to its identity as an LGBT-friendly community. The park was created after a large fire in 1835 devastated an overcrowded tenement on the site. Neighborhood residents persuaded the City to condemn the approximately 0.12-acre triangle for public open space in 1837. By the 1960s, Christopher Park had become a popular destination for LGBT youth, many of whom had run away from or been kicked out of their homes. These youth and others who had been similarly oppressed felt they had little to lose when the community clashed with the police during the Stone- wall Uprising. In the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, a riot broke out in response to a police raid on the Stonewall Inn, at the time one of the City’s best known LGBT bars. -

SENATE JUD COMMITTEE -1- January 25, 2012 POSITION STATEMENT: Delivered a Presentation to the Crime Summit

ALASKA STATE LEGISLATURE SENATE JUDICIARY STANDING COMMITTEE January 25, 2012 8:37 a.m. MEMBERS PRESENT Senator Hollis French, Chair Senator Bill Wielechowski, Vice Chair Senator Joe Paskvan Senator Lesil McGuire Senator John Coghill MEMBERS ABSENT All members present OTHER LEGISLATORS PRESENT Senator Gary Stevens Senator Johnny Ellis Senator Fred Dyson Representative Pete Petersen COMMITTEE CALENDAR CRIME SUMMIT - HEARD PREVIOUS COMMITTEE ACTION No previous action to record WITNESS REGISTER ERIN PATTERSON-SEXSON, Lead Advocate Direct Services Coordinator Standing Together Against Rape Anchorage, AK POSITION STATEMENT: Delivered a presentation to the Crime Summit. NANCY MEADE, General Counsel Alaska Court System Anchorage, AK SENATE JUD COMMITTEE -1- January 25, 2012 POSITION STATEMENT: Delivered a presentation to the Crime Summit. DIANE SCHENKER, Project Coordinator Fairbanks Electronic Bail Conditions Project Alaska Court System Anchorage, AK POSITION STATEMENT: Delivered a presentation to the Crime Summit. HELEN SHARRATT, Integrated Justice Coordinator Alaska Court System and Coordinator for MAJIC Anchorage, AK POSITION STATEMENT: Delivered a presentation to the Crime Summit. QUINLAN STEINER, Director Public Defender Agency Department of Administration Anchorage, AK POSITION STATEMENT: Delivered a presentation to the Crime Summit. RICHARD ALLEN, Director Office of Public Advocacy Department of Administration Anchorage, AK POSITION STATEMENT: Delivered a presentation to the Crime Summit. WALT MONEGAN, President and CEO Alaska Native Justice Center Anchorage, AK POSITION STATEMENT: Delivered a presentation to the Crime Summit. JAKE METCALFE, Executive Director Public Safety Employee Association Anchorage, AK POSITION STATEMENT: Delivered a presentation to the Crime Summit. TERRENCE SHANIGAN, Trooper Alaska State Troopers Department of Public Safety Talkeetna, AK SENATE JUD COMMITTEE -2- January 25, 2012 POSITION STATEMENT: Delivered a presentation to the Crime Summit. -

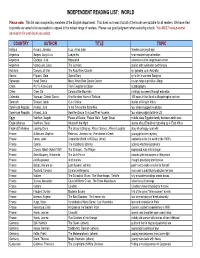

Independent Reading List: World

INDEPENDENT READING LIST: WORLD Please note: This list was compiled by members of the English department. That does not mean that all of the books are suitable for all readers. We have tried to provide as varied a list as possible to appeal to the widest range of readers. Please use good judgment when selecting a book. You MUST have parental permission for each book you select. COUNTRY AUTHOR TITLE TOPIC Antigua Kincaid, Jamaica Lucy, Annie John females coming of age Argentina Borges, Jorge Luis Labyrinths short stories/magical realism Argentina Cortazar, Julio Hopscotch adventures of an Argentinean writer Argentina Valenzuela, Luisa The Censors stories with symbolism and fantasy Australia Conway, Jill Ker The Road from Coorain girl growing up in Australia Bosnia Filipovic, Zlata Zlata's Diary girl's life in war-torn Sarajevo Botswana Head, Bessie Maru; When Rain Clouds Gather ex-con helps a primitive village China P'u Yi, Aisin-Gioro From Emperor to Citizen autobiography China Chen, Da Colors of the Mountain rural boy succeeds through education Colombia Marquez, Gabriel Garcia One Hundred Years of Solitude 100 years in the life of a village/magical realism Denmark Dinesen, Isaak Out of Africa stories of living in Africa Dominican Republic Alvarez, Julia In the Time of the Butterflies four sisters support revolution Dominican Republic Alvarez, Julia How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents four sisters adjust to life in US Egypt Mahfouz, Naguib Palace of Desire; Palace Walk; Sugar Street middle class Egyptian family between world wars -

5.6 Herbicides in Warfare: the Case of Indochina A

Ecotoxicology and Climate Edited by P. Bourdeau, J. A. Haines, W. Klein and C. R. Krishna Murti @ 1989 SCOPE. Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd 5.6 Herbicides in Warfare: The Case of Indochina A. H. WESTING 5.6.1 INTRODUCTION The Second Indochina War (or Vietnam Conflict) of 1961-1975 is noted for the widespread and severe environmental damage inflicted upon its theatre of operations, especially in the former South Vietnam (Westing, 1976, 1980, 1982a, 1984b). The US strategy in South Vietnam, inter alia, involved massive rural area bombing, extensive chemical and mechanical forest destruction, large-scale chemical and mechanical crop destruction, wide-ranging chemical anti-personnel harassment and area denial, and enormous forced population displacements. In short, this US strategy represented the intentional disruption of both the natural and human ecologies of the region. Moreover, this war was the first in military history in which massive quantities of anti-plant chemical warfare agents (herbicides) were employed (Buckingham, 1982;Cecil, 1986; Lang et al., 1974; Westing, 1976, 1984b). The Second Indochina War was innovative in that a great power attempted to subdue a peasant army through the profligate use of technologically advanced weapons and methods. One can readily understand that the outcome of more than a decade of such war in South Vietnam and elsewhere in the region resulted not only in heavy direct casualties, but also in long-term medical sequelae. By any measure, however, its main effects were a widespread, long-lasting, and severe disruption of forestlands, of perennial croplands, and of farmlands- that is to say, of millions of hectares of the natural resource base essential to an agrarian society. -

Theire Journal

CONTENTS 20 A MUCKRAKING LIFE THE IRE JOURNAL Early investigative journalist provides relevant lessons TABLE OF CONTENTS By Steve Weinberg MAY/JUNE 2003 The IRE Journal 4 IRE gaining momentum 22 – 31 FOLLOWING THE FAITHFUL in drive for “Breakthroughs” By Brant Houston PRIEST SCANDAL The IRE Journal Globe court battle unseals church records, 5 NEWS BRIEFS AND MEMBER NEWS reveals longtime abuse By Sacha Pfeiffer 8 WINNERS NAMED The Boston Globe IN 2002 IRE AWARDS By The IRE Journal FAITH HEALER Hidden cameras help, 12 2003 CONFERENCE LINEUP hidden records frustrate FEATURES HOTTEST TOPICS probe into televangelist By MaryJo Sylwester By Meade Jorgensen USA Today Dateline NBC 15 BUDGET PROPOSAL CITY PORTRAITS Despite economy, IRE stays stable, Role of religion increases training and membership starkly different By Brant Houston in town profiles The IRE Journal By Jill Lawrence USA Today COUNTING THE FAITHFUL 17 THE BLACK BELT WITH CHURCH ROLL DATA Alabama’s Third World IMAM UPROAR brought to public attention By Ron Nixon Imam’s history The IRE Journal By John Archibald, Carla Crowder hurts credibility and Jeff Hansen on local scene The Birmingham News By Tom Merriman WJW-Cleveland 18 INTERVIEWS WITH THE INTERVIEWERS Confrontational interviews By Lori Luechtefeld 34 TORTURE The IRE Journal Iraqi athletes report regime’s cruelties By Tom Farrey ESPN.com ABOUT THE COVER 35 FOI REPORT Bishop Wilton D. Gregory, Paper intervenes in case to argue for public database president of the U. S. Conference By Ziva Branstetter of Catholic Bishops, listens to a Tulsa World question after the opening session of the conference. -

Anarchism and the Black Revolution

Anarchism and the Black Revolution Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin 1993 Contents Dedication For the second edition of Anarchism and the Black Revolution . 4 Chapter 1. An Analysis of White Supremacy 5 How the Capitalists Use Racism .............................. 5 Race and Class: the Combined Character of Black Oppression .............. 6 So What Type of Anti-Racist Group is Needed? ...................... 7 The Myth of “Reverse Racism” ............................... 8 Smash the right Wing! .................................... 10 Defeat white supremacy! .................................. 12 Chapter 2. Where is the Black struggle and where should it be going? 16 A Call for a New Black Protest Movement ......................... 17 What form will this movement take? ............................ 18 Revolutionary strategy and tactics ............................. 19 A Black Tax Boycott ..................................... 19 A National Rent Strike and Urban Squatting ........................ 20 A Boycott of American Business .............................. 20 A Black General Strike ................................... 21 The Commune: Community Control of the Black Community . 23 Building A Black survival program ............................. 26 The Need for a Black Labor Federation ........................... 28 Unemployment and Homelessness ............................. 32 Crimes Against the People ................................. 35 The Drug Epidemic: A New Form of Black Genocide? . 38 African Intercommunalism ................................. 40 Armed -

UWM Police Guns Spur Debate SA Housing Service Enforces State

I N I •SANDBURG: Asbestos removal in residence halls to take years •MCGEE: Black Panther Militia one part of community plan for unity •THEATRE X season finale proves a Success •TRACK recap and looking ahead to next year with Coach Corfield Wednesday, June 20, 1990 Volume 34, Number 52 Happy Juneteenth Day SA Housing Service enforces state statute by Bill Meyer News Edjtor • he Off Campus Housing and Referral Service has revised its policies for housing advertisements to comply with the Wisconsin TStatutes on equal rights in housing, according to Jacqueline Sciuti, manager of the service. As a result, roommate-wanted ads and ads for rooms in owner-occupied, single-family residences placed through the service may not be gender-specific. Sciuti, who made the revision in May, said that the new policy was initiated in order to comply with a 1988 change in the state statutes. "We were just made aware of that recently. There was a complaint tak en to the fair housing board by a student," said Sciuti. The section of the statute in question, sec. 101.22, states that "the legislature hereby extends the state law governing equal housing opportunities to cover single-family residences which are owner occupied ... the sale and rental of single- family residences of single- family residences constitute a significant portion of the housing busi ness in this state and should be regulated." There is no specific mention of roomate-wanted ads, but the statute does prohibit "publishing, circulating, issuing or displaying . any communication, notice, advertisement or sign in connection with the —Post photo by Robert Schatzman sale, financing, lease or rental of housing, which states or indicates any Children attending Tuesday's Juneteenth Day parade on W. -

Accessibility, Quality, and Profitability for Personal Plight Law Firms: Hitting the Sweet Spot

ACCESSIBILITY, QUALITY, AND PROFITABILITY FOR PERSONAL PLIGHT LAW FIRMS: HITTING THE SWEET SPOT By Noel Semple Prepared for the Canadian Bar Association Futures Initiative ACCESSIBILITY, QUALITY, AND PROFITABILITY FOR PERSONAL PLIGHT LAW FIRMS: HITTING THE SWEET SPOT August 2017 © Canadian Bar Association. 865 Carling Avenue, Suite 500, Ottawa, ON K1S 5S8 Tel.: (613) 237-2925 / (800) 267-8860 / Fax: (613) 237-0185 E-mail: [email protected] Home page: www.cba.org Website: cbafutures.org ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No portion of this paper may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. Printed in Canada Sommaire disponible en français The views expressed in this report are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the Canadian Bar Association. ISBN: 978-1-927014-41-7 2 ACCESSIBILITY, QUALITY, AND PROFITABILITY FOR PERSONAL PLIGHT LAW FIRMS: HITTING THE SWEET SPOT ACCESSIBILITY, QUALITY, AND PROFITABILITY FOR PERSONAL PLIGHT LAW FIRMS: HITTING THE SWEET SPOT By Noel Semple1 Prepared for the Canadian Bar Association Futures Initiative. ABSTRACT Personal plight legal practice includes all legal work for individual clients whose needs arise from disputes. This is the site of our worst access to justice problems. The goal of this project is to identify sustainable innovations that can make the services of personal plight law firms more accessible to all Canadians. Accessibility is vitally important, but it is not the only thing that matters in personal plight legal practice. Thus, this book seeks out innovations that not only improve accessibility, but also preserve or enhance service quality as well as law firms’ profitability.