Community Archaeological Excavation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall Neighbourhood Plan Includes Policies That Seek to Steer and Guide Land-Use Planning Decisions in the Area

Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall Neighbourhood Development Plan 2017 - 2030 December 2017 1 | Page Contents 1.1 Foreword ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 5 2. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Neighbourhood Plans ............................................................................................................... 6 2.2 A Neighbourhood Plan for Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall ........................................ 6 2.3 Planning Regulations ................................................................................................................ 8 3. BEESTON, TIVERTON AND TILSTONE FEARNALL .......................................................................... 8 3.1 A Brief History .......................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Village Demographic .............................................................................................................. 10 3.3 The Villages’ Economy ........................................................................................................... 11 3.4 Community Facilities ............................................................................................................ -

Issues and Options Topic Papers

Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council Local Development Framework Joint Core Strategy and Development Management Policies Development Plan Document Issues and Options Topic Papers February 2012 Strategic Planning Tameside MBC Room 5.16, Council Offices Wellington Road Ashton-under-Lyne OL6 6DL Tel: 0161 342 3346 Email: [email protected] For a summary of this document in Gujurati, Bengali or Urdu please contact 0161 342 8355 It can also be provided in large print or audio formats Local Development Framework – Core Strategy Issues and Options Discussion Paper Topic Paper 1 – Housing 1.00 Background • Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing (PPS3) • Regional Spatial Strategy North West • Planning for Growth, March 2011 • Manchester Independent Economic Review (MIER) • Tameside Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) • Tameside Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2008 (SHMA) • Tameside Unitary Development Plan 2004 • Tameside Housing Strategy 2010-2016 • Tameside Sustainable Community Strategy 2009-2019 • Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessment • Tameside Residential Design Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) 1.01 The Tameside Housing Strategy 2010-2016 is underpinned by a range of studies and evidence based reports that have been produced to respond to housing need at a local level as well as reflecting the broader national and regional housing agenda. 2.00 National Policy 2.01 At the national level Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing (PPS3) sets out the planning policy framework for delivering the Government's housing objectives setting out policies, procedures and standards which Local Planning Authorities must adhere to and use to guide local policy and decisions. 2.02 The principle aim of PPS3 is to increase housing delivery through a more responsive approach to local land supply, supporting the Government’s goal to ensure that everyone has the opportunity of living in decent home, which they can afford, in a community where they want to live. -

Geoffrey of Dutton, the Fifth Crusade, and the Holy Cross of Norton

A Transformed Life? Geoffrey of Dutton, the Fifth Crusade, and the Holy Cross of Norton. Despite the volume of scholarship dedicated to crusade motivation, comparative little has been said on how the crusades affected the lives of individuals, and how this played out once the returned home. Taking as a case study a Cheshire landholder, Geoffrey of Dutton, this article looks at the reasons for his crusade participation and his actions once he returned to Cheshire, arguing that he was changed by his experiences to the extent that he was concerned with remembering and conveying his own status as a returned pilgrim. It also looks at the impact of a relic of the True Cross he brought back and gave to the Augustinian priory of Norton. Keywords: crusade; relic; Norton Priory; burial; seal An extensive body of scholarship has considered what motivated people to go on crusade in the middle ages (piety, obligation and service, family connections and ties of lordship, punishment and escape), as well as what impact that had across Europe in terms of recruitment, funding and organisation. Far less has been said about the more personal impact of crusading for individuals who took part. This is largely due to the nature of the sources from which, according to Housley, ‘not much can be inferred…about the response of the majority of crusaders to what they’d gone through in the East.’1 With the exception of accounts of the post-crusading careers of the most important individuals, notably Louis IX of France, very little was written about how crusaders responded to taking part in an overseas campaign which mixed the height of spiritual endeavour with extreme violence. -

Halton Grange Page 1 of 4 SITE NAME: Address Halton Grange (Runcorn Town Hall), Heath Road, Runcorn, WA7 5TD Unitary Authority

SITE NAME: Halton Grange (Runcorn Town Hall), Heath Road, Runcorn, WA7 5TD Address Unitary Halton Borough Council Authority: Parish: Runcorn Location: 0.5km south of Runcorn Town centre Grid Ref: SJ 518 820. Owner: Halton Borough Council Recorder: JC Date of Site Visit 20.04.2016 Date of Report: 29/04/17 Summary Halton Grange was built in the 1850s as a residential property for a local soap manufacturer. The grounds were laid out in 1853-4 by Edward Kemp. In 1932 the property and a small portion of the surrounding land were sold to Runcorn District Council who took it over as council offices. Many original features survive inside the building and elements of Kemp’s layout and features remain in the grounds. The kitchen garden has been lost to council offices. Halton Grange is now known as Runcorn Town Hall and belongs to Halton Borough Council. Principal remaining features House, listed Grade II (List Entry Number: 1104859) The long walk Sandstone retaining wall with niche Sections of wall associated with the kitchen garden and outbuildings An ornamental pond Parkland trees History (numbers in brackets refer to images, letters in brackets refer to maps) The earliest record in the deeds of Halton Grange is August 1778 when Thomas Fearnhead was granted a tenancy of land owned by the Duchy of Lancaster, by The Court of the Manor of Halton. In December 1780, the tenancy passed to Daniel Orred and then to his nephew, George Orred upon his death. The total land holding was described as 14 Cheshire acres. At the Manor Court in 1836 evidence was given of the grant to George Orred of the tenancy, of its subsequent transfer to William Johnson (victualler) for £1,900, and of a further transfer to Francis Salkeld (grocer) in 1830 for the sum of £3,720. -

Levens Hall & Gardens

LAKE DISTRICT & CUMBRIA GREAT HERITAGE 15 MINUTES OF FAME www.cumbriaslivingheritage.co.uk Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal Cumbria Living Heritage Members’ www.abbothall.org.uk ‘15 Minutes of Fame’ Claims Cumbria’s Living Heritage members all have decades or centuries of history in their Abbot Hall is renowned for its remarkable collection locker, but in the spirit of Andy Warhol, in what would have been the month of his of works, shown off to perfection in a Georgian house 90th birthday, they’ve crystallised a few things that could be further explored in 15 dating from 1759, which is one of Kendal’s finest minutes of internet research. buildings. It has a significant collection of works by artists such as JMW Turner, J R Cozens, David Cox, Some have also breathed life into the famous names associated with them, to Edward Lear and Kurt Schwitters, as well as having a reimagine them in a pop art style. significant collection of portraits by George Romney, who served his apprenticeship in Kendal. This includes All of their claims to fame would occupy you for much longer than 15 minutes, if a magnificent portrait - ‘The Gower Children’. The you visited them to explore them further, so why not do that and discover how other major piece in the gallery is The Great Picture, a interesting heritage can be? Here’s a top-to-bottom-of-the-county look at why they triptych by Jan van Belcamp portraying the 40-year all have something to shout about. struggle of Lady Anne Clifford to gain her rightful inheritance, through illustrations of her circumstances at different times during her life. -

Former Regimental HQ

TO Former Regimental HQ LET Carlisle Castle, Carlisle, CA3 8UR t: 01228 514199 e: [email protected] UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY TO BE BASED WITHIN HISTORICAL CARLISLE CASTLE www.waltongoodland.com CUMBERLAND DEVONSHIRE WALK INFIRMARY CAR PARK SUBJECT PROPERTY CARLISLE CASTLE A595 BITTS PARK CARLISLE CATHEDRAL CASTLE CARLISLE WAY MARKET HALL CASTLE FISHER STREET STREET TOWN GREENMARKET HALL SCOTCH STREET PEDESTRIANISED CITY CENTRE t: 01228 514199 e: [email protected] www.waltongoodland.com KEY HIGHLIGHTS Grade II listed sandstone building approximately 2,257 sq ft (210 sq m) Prominently located above busy principal route (A595) to west of Carlisle/Cumbria Potential use opportunities include alternative Leisure/Events, Restaurant/Bistro, Offices all uses subject to planning Excellent access to road and infrastructure links: Carlisle City Centre: 500m M6/A69 (Junc 43): 3 miles Grade II listed building with excellent Penrith: 22 miles Lake District National Park: 25 miles views overlooking Castle grounds Scottish Borders: 10 miles t: 01228 514199 e: [email protected] www.waltongoodland.com LOCATION The property comprises a former Regimental HQ and Officers Mess located within Carlisle Castle, being prominently positioned above the City of Carlisle. The Castle occupies a 4-acre site formerly occupied by the military, which is now preserved by English Heritage, who occupy the site alongside Cumbria’s Museum of Military Life. Located opposite the site via a subway connection is Tullie House Museum, leading to Carlisle Cathedral and the main City Centre retail core. The property sits alongside Castle Way, the main A595 trunk route to the west of Carlisle and Cumbria, with access to the M6/A69 (junction 43) within 3 miles. -

Index to Gallery Geograph

INDEX TO GALLERY GEOGRAPH IMAGES These images are taken from the Geograph website under the Creative Commons Licence. They have all been incorporated into the appropriate township entry in the Images of (this township) entry on the Right-hand side. [1343 images as at 1st March 2019] IMAGES FROM HISTORIC PUBLICATIONS From W G Collingwood, The Lake Counties 1932; paintings by A Reginald Smith, Titles 01 Windermere above Skelwith 03 The Langdales from Loughrigg 02 Grasmere Church Bridge Tarn 04 Snow-capped Wetherlam 05 Winter, near Skelwith Bridge 06 Showery Weather, Coniston 07 In the Duddon Valley 08 The Honister Pass 09 Buttermere 10 Crummock-water 11 Derwentwater 12 Borrowdale 13 Old Cottage, Stonethwaite 14 Thirlmere, 15 Ullswater, 16 Mardale (Evening), Engravings Thomas Pennant Alston Moor 1801 Appleby Castle Naworth castle Pendragon castle Margaret Countess of Kirkby Lonsdale bridge Lanercost Priory Cumberland Anne Clifford's Column Images from Hutchinson's History of Cumberland 1794 Vol 1 Title page Lanercost Priory Lanercost Priory Bewcastle Cross Walton House, Walton Naworth Castle Warwick Hall Wetheral Cells Wetheral Priory Wetheral Church Giant's Cave Brougham Giant's Cave Interior Brougham Hall Penrith Castle Blencow Hall, Greystoke Dacre Castle Millom Castle Vol 2 Carlisle Castle Whitehaven Whitehaven St Nicholas Whitehaven St James Whitehaven Castle Cockermouth Bridge Keswick Pocklington's Island Castlerigg Stone Circle Grange in Borrowdale Bowder Stone Bassenthwaite lake Roman Altars, Maryport Aqua-tints and engravings from -

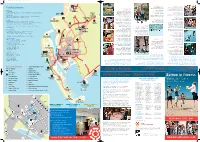

Barrow Map Leaflet 28728 11/1/07 12:06 Page 1

Barrow Map Leaflet_28728 11/1/07 12:06 Page 1 Tel: 01229 474251. 01229 Tel: Tel: 01229 430600. 01229 Tel: WC u School. Riding Seaview specially trained owls/bird of prey. of owls/bird trained specially by the sea with sea the by horse a Ride Travelling to Barrow 835449. 01229 Tel: ASKAM from displays regular as well as diverse night life. life. night diverse - see a variety of owls of variety a see - owls Furness - IN - trails. waymarked BY CAR q and lively having for reputation countryside and seaside and countryside which adds further to the town’s the to further adds which From The M6 FURNESS 824334. 01229 Tel: the network of network the A595 Walk on board the Princess Selandia, Princess the board on Leave the Motorway at junction 36, then follow the A590 all the way to Barrow. restaurant. family and ROANHEAD LINDAL state of the art floating nightspot floating art the of state - indoor play area play indoor - BEACH Warehouse Wacky - IN - courses. excellent 3 Barrow’s is Barrow’s latest Barrow’s is From The Lakes Lagoon Blue The enthusiasts can play on play can enthusiasts Golf Take the A592 from Bowness along the Eastern shore of Lake Windermere. FURNESS A590 823823. 01229 Tel: Tel: 01229 823823 01229 Tel: Lazerzone. of Join the A590 which takes you straight to Barrow. t SOUTH LAKES WILD eatery. stylish and WC 470303. 01229 Tel: bar, childrens play area and venue and area play childrens bar, - indoor play area area play indoor - ANIMAL PARK Playzone West Kitesurfing. West - stylish eatery, stylish - BY TRAIN House Custom The railway and play areas. -

Rehabilitation of Brougham Castle Bridge, UK

Cite this article Research Article Keywords: brickwork & masonry/ Wiggins D, Mudd K and Healey M (2019) Paper 1800027 bridges/conservation Rehabilitation of Brougham Castle Bridge, UK. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers Received 17/08/2018; Accepted 01/10/2018 – Engineering History and Heritage 172(1):7–18, https://doi.org/10.1680/jenhh.18.00027 Published online 30/10/2018 ICE Publishing: All rights reserved Engineering History and Heritage Rehabilitation of Brougham Castle Bridge, UK 1 David Wiggins BSc(Hons), PhD, IEng, MICE 3 Matthew Healey HNC, ONC Senior Conservation-Accredited Engineer, Curtins, Kendal, UK Contracts Director, Civil Engineering, Metcalfe Plant Hire Ltd, Penrith, (corresponding author: [email protected]) UK 2 Kiera Mudd MEng(Hons) Engineer, Curtins, Leeds, UK 1 2 3 Brougham Castle Bridge is a three-span masonry arch highway bridge that has suffered significant scour damage to foundations and substructure with referred damage through the superstructure. This paper presents an engineer’s account of the appraisal, investigation, assessment of structural action and the design and execution of repairs for stabilising the structure. The analytical tool employed to interpret the flow of force was a thrust-line graphical equilibrium analysis. It will be demonstrated that this analytical approach accords with the observed structural pathology, thus giving a clear understanding as to where the loads are going, that they may be effectively grappled with. Through thrust-line analysis, continued stability could be demonstrated despite substantial changes in the foundation conditions. It seems fitting that this efficient, robust and confidence-building tool is the same used by the engineers who originally designed many of these bridges. -

Halton Village CAA and MP:Layout 1.Qxd

Halton Village Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan 1 HALTON VILLAGE CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL AND MANAGEMENT PLAN PUBLIC CONSULTATION DRAFT 2008 This document has been produced in partnership with Donald Insall Associates ltd, as it is based upon their original appraisal completed in april 2008. if you wish to see a copy of the original study, please contact Halton Borough Council's planning and policy division. Cover Photo courtesy of Norton Priory Museum Trust and Donald Insall Associates. Operational Director Environmental Health and Planning Environment Directorate Halton Borough Council Rutland House Halton Lea Runcorn WA7 2GW www.halton.gov.uk/forwardplanning 2 CONTENTS APPENDICES PREFACE 1.7 NEGATIVE FACTORS A Key Features Plans Background to the Study 1.7.1 Overview B Gazetteer of Listed Scope and Structure of the Study 1.7.2 Recent Development Buildings Existing Designations and Legal 1.7.3 Unsympathetic Extensions C Plan Showing Contribution Framework for Conservation Areas 1.7.4 Unsympathetic Alterations of Buildings to the and the Powers of the Local Authority 1.7.5 Development Pressures Character of the What Happens Next? 1.7.6 Loss Conservation Area 1.8 CONCLUSION D Plan Showing Relative Ages PART 1 CONSERVATION AREA of Buildings APPRAISAL PART 2 CONSERVATION AREA E Plans Showing Existing and MANAGEMENT PLAN Proposed Conservation 1.1 LOCATION Area Boundaries 1.1.1 Geographic Location 2.1 INTRODUCTION F Plan Showing Area for 1.1.2 Topography and Geology 2.2 GENERAL MANAGEMENT Proposed Article 4 1.1.3 General -

Download Brochure

2020 Your Holiday with Byways Short Cycling Breaks 4 Longer Cycling Breaks 7 Walking holidays 10 Walkers accommodation booking and luggage service 12 More Information 15 How Do I Book? 16 How Do I Get There? 16 The unspoilt, countryside of Wales, maps and directions highlighting things Shropshire and Cheshire is a lovely area to see and do along the way. We for cycling and walking. Discover move your luggage each day so you beautiful countryside, pretty villages, travel light, with just what you need for quiet rural lanes and footpaths, as well the day, and we are always just a as interesting places to visit and great phone call away if you need our help. pubs and tea shops. Customer feedback is very important With more than 20 years experience, we to us and our feedback continues to know the area inside-out. Our routes are be excellent, with almost everyone carefully planned so you explore the rating their holiday with us as best of the countryside, stay in the ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’. We are nicest places and eat good, local food. continuing to get many customers Holidays are self-led, so you have the returning for another holiday with us or freedom to explore at your own pace, recommending us to their friends. take detours stopping when and where Our Walkers’ Accommodation Booking you want. Routes are graded (gentle, and Luggage Service on the longer moderate or strenuous) and flexible - distance trail walks continues to be we can tailor holidays to suit specific very popular. Offa’s Dyke is always requirements - so there's something for busy as is the beautiful Pembrokeshire all ages and abilities. -

Brindley Archer Aug 2011

William de Brundeley, his brother Hugh de Brundeley and their grandfather John de Brundeley I first discovered William and Hugh (Huchen) Brindley in a book, The Visitation of Cheshire, 1580.1 The visitations contained a collection of pedigrees of families with the right to bear arms. This book detailed the Brindley family back to John Brindley who was born c. 1320, I wanted to find out more! Fortunately, I worked alongside Allan Harley who was from a later Medieval re-enactment group, the ‘Beaufort companye’.2 I asked if his researchers had come across any Brundeley or Brundeleghs, (Medieval, Brindley). He was able to tell me of the soldier database and how he had come across William and Hugh (Huchen) Brundeley, archers. I wondered how I could find out more about these men. The database gave many clues including who their captain was, their commander, the year of service, the type of service and in which country they were campaigning. First Captain Nature of De Surname Rank Commander Year Reference Name Name Activity Buckingham, Calveley, Thomas of 1380- Exped TNA William de Brundeley Archer Hugh, Sir Woodstock, 1381 France E101/39/9 earl of Buckingham, Calveley, Thomas of 1380- Exped TNA Huchen de Brundeley Archer Hugh, Sir Woodstock, 1381 France E101/39/9 earl of According to the medieval soldier database (above), the brothers went to France in 1380-1381 with their Captain, Sir Hugh Calveley as part of the army led by the earl of Buckingham. We can speculate that William and Hugh would have had great respect for Sir Hugh, as he had been described as, ‘a giant of a man, with projecting cheek bones, a receding hair line, red hair and long teeth’.3 It appears that he was a larger than life character and garnered much hyperbole such as having a large appetite, eating as much as four men and drinking as much as ten.