Brindley Archer Aug 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall Neighbourhood Plan Includes Policies That Seek to Steer and Guide Land-Use Planning Decisions in the Area

Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall Neighbourhood Development Plan 2017 - 2030 December 2017 1 | Page Contents 1.1 Foreword ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 5 2. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Neighbourhood Plans ............................................................................................................... 6 2.2 A Neighbourhood Plan for Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall ........................................ 6 2.3 Planning Regulations ................................................................................................................ 8 3. BEESTON, TIVERTON AND TILSTONE FEARNALL .......................................................................... 8 3.1 A Brief History .......................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Village Demographic .............................................................................................................. 10 3.3 The Villages’ Economy ........................................................................................................... 11 3.4 Community Facilities ............................................................................................................ -

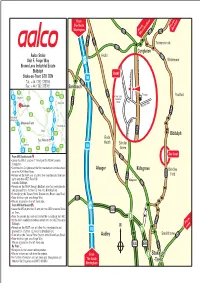

Stoke-On-Trent ST8 7DN A

From The North From Warrington Buxton A54 From A54 MacclesfieldA34 A50 Timbersbrook A5022 A534 Congleton Aalco Stoke Arclid A527 J17 T Whitemoor Unit F, Forge Way u n s Brown Lees Industrial Estate t al A34 Biddulph l R Inset y o a Stoke-on-Trent ST8 7DN a W M6 d A533 e Brown Le g Tel: +44 1782 375700 r o Fax: +44 1782 375701 Sandbach F A50 A34 A60 e Texaco Brown Lees s Poolfold M6 Congleton A614 A53 M1 Industrial R Estate oad J17 A6 Mansfield ay A534 ria W Biddulph Victo J28 A533 A38 J16 A52 A527 Newcastle- Under-Lyme J26 ay W J15 Stoke-on-Trent t c Nottingham e p A53 A50 J25 s Derby o r A527 A453 P Biddulph A34 J24 Rode East Midlands A34 Heath Scholar Stafford A46 M6 A38 Green M6 A51 A42 M1 A6 See Inset From M6 Southbound A50 Leave the M6 at junction 17 and join the A534 towards Congleton. A533 Continue into Congleton at the first roundabout continue ahead Alsager Kidsgrove Brindley onto the A34 West Road. Remain on the A34 over a further two roundabouts then turn Ford A527 right onto the A527 Rood Hill. A34 Kidsgrove A50 towards Biddulph. Remain on the A534 through Biddulph over four roundabouts and proceed for a further 1/2 mile into Brindley Ford. Turn right at the Texaco Petrol Station onto Brown Lees Road. Take the first right onto Forge Way. A500 We are situated on the left hand side. From M6 Northbound J16 Leave the M6 at junction 16 and join the A500 towards Stoke A500 on Trent. -

THE ANCIENT BOKOUGH of OVER, CHESHIRE. by Thomas Rigby Esq

THE ANCIENT BOKOUGH OF OVER, CHESHIRE. By Thomas Rigby Esq. (RsiD IST DECEMBER, 1864.J ALMOST every village has some little history of interest attached to it. Almost every country nook has its old church, round which moss-grown gravestones are clustered, where The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep. These lithic records tell us who lived and loved and laboured at the world's work long, long ago. Almost every line of railroad passes some ivy-mantled ruin that, in its prime, had armed men thronging on its embattled walls. Old halls, amid older trees old thatched cottages, with their narrow windows, are mutely eloquent of the past. The stories our grandfathers believed in, we only smile at; but we reverence the spinning wheel, the lace cushion, the burnished pewter plates, the carved high-backed chairs, the spindle-legged tables, the wainscoted walls and cosy " ingle nooks." Hath not each its narrative ? These are all interesting objects of the bygone time, and a story might be made from every one of them, could we know where to look for it. With this feeling I have undertaken to say a few words about the ancient borough of Over in Cheshire, where I reside; and, although the notes I have collected may not be specially remarkable, they may perhaps assist some more able writer to complete a record of more importance. Over is a small towu, nearly in the centre of Cheshire. It consists of one long street, crossed at right angles by Over u Lane, which stretches as far as Winsford, and is distant about two miles from the Winsford station on the London and North-Western Railway. -

5388 North View, NANTWICH ROAD, CALVELEY

Site ref: 5388 North View, NANTWICH ROAD, CALVELEY Commitments at 31 March 2019 Permission Type No of units Decision date reference 16/2950N Outline 16 24-May-17 Site Progress A small site of less than 1 hectare in size. The council's evidence of lead in times and build rates for small sites demonstrates that such sites are often built quickly and within one or two years. Paragraph 68 of the NPPF also 16/2950N acknowledges that such sites will often be built out relatively quickly. The sale of the site has now been agreed. There is a realistic prospect that all housing will be delivered on site within five years. Five Year Forecast 01/04/2019 01/04/2020 01/04/2021 01/04/2022 01/04/2023 Permission to to to to to Total reference 31/03/2020 31/03/2021 31/03/2022 31/03/2023 31/03/2024 16/2950N 0 0 0 8 8 16 OFFICIAL-SENSITIVE 5/22/2019 Development Site for sale in Residential Dev Land at North View, Calveley, Tarporley, Cheshire, CW6 | Fisher German (/) (/my-account) (/my-account/update-your-prole) Back Save Property (/my-account) 1 of 7 Development Site For Sale Residential Dev Land at North View, Calveley, Tarporley, Cheshire CW6 Guide price £1,300,000 Sale Agreed Michael Harris (/team/308-michael-harris-1da2) Enquire Call Us https://www.fishergerman.co.uk/residential-property-sales/development-site-for-sale-in-calveley-tarporley-cheshire-cw6/26947 1/6 5/22/2019 Development Site for sale in Residential Dev Land at North View, Calveley, Tarporley, Cheshire, CW6 | Fisher German 01244 409660 (tel:01244409660) Email (/contact-team?tid=308&pid=26947)(/) (/my-account) (/my-account/update-your-prole) A prime residential development opportunity in a sought after South Cheshire village, with outline planning approval for up to 16 houses. -

Our Local Offer for Special Educational Needs And/Or Disability

Our Local Offer for Special Educational Needs and/or Disability Please click the relevant words on the wheel to be Area Wide Local Offer taken toNEP.png the NEP.png corresponding section. Teaching, Identification Learning & Support Keeping Additional Students Safe & Information Supporting Wellbeing Working Transition Together & Please see the following Roles page for information on Inclusion & this setting’s age range Accessibility and setting type Part of Nantwich Education Partnership Our Local Offer for Special Educational Needs and/or Disability --------------------------------------------------------------- Click here to return to the front page ---------------------------------------------------------- Name of Setting Wrenbury Primary School Type of Setting Mainstream Resourced Provision Special (tick all that apply) Early Years Primary Secondary Post-16 Post-18 Maintained Academy Free School Independent/Non-Maintained/Private Other (Please Specify) Specific Age 4-11 range Number of places Published Admission Number 20 pupils per year group. Currently 130 on roll. Which types of special We are an inclusive mainstream setting catering for We are an inclusive setting that offers a specialism/specialisms in educational need children and young people with a wide range of needs do you cater for? who are able to demonstrate capacity for accessing the (IRR) mainstream curriculum with differentiation and support. Each section provides answers to questions from the Parent/Carer’s Point of View. The questions have been developed using examples from Pathfinder authorities, such as the SE7 Pathfinder Partnership, in conjunction with questions from Cheshire East parent carers. The requirements for the SEN Information Report have been incorporated into this document, based on the latest draft version of the Special Educational Needs (Information) Regulations (correct as of May 2014). -

Halton Village CAA and MP:Layout 1.Qxd

Halton Village Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan 1 HALTON VILLAGE CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL AND MANAGEMENT PLAN PUBLIC CONSULTATION DRAFT 2008 This document has been produced in partnership with Donald Insall Associates ltd, as it is based upon their original appraisal completed in april 2008. if you wish to see a copy of the original study, please contact Halton Borough Council's planning and policy division. Cover Photo courtesy of Norton Priory Museum Trust and Donald Insall Associates. Operational Director Environmental Health and Planning Environment Directorate Halton Borough Council Rutland House Halton Lea Runcorn WA7 2GW www.halton.gov.uk/forwardplanning 2 CONTENTS APPENDICES PREFACE 1.7 NEGATIVE FACTORS A Key Features Plans Background to the Study 1.7.1 Overview B Gazetteer of Listed Scope and Structure of the Study 1.7.2 Recent Development Buildings Existing Designations and Legal 1.7.3 Unsympathetic Extensions C Plan Showing Contribution Framework for Conservation Areas 1.7.4 Unsympathetic Alterations of Buildings to the and the Powers of the Local Authority 1.7.5 Development Pressures Character of the What Happens Next? 1.7.6 Loss Conservation Area 1.8 CONCLUSION D Plan Showing Relative Ages PART 1 CONSERVATION AREA of Buildings APPRAISAL PART 2 CONSERVATION AREA E Plans Showing Existing and MANAGEMENT PLAN Proposed Conservation 1.1 LOCATION Area Boundaries 1.1.1 Geographic Location 2.1 INTRODUCTION F Plan Showing Area for 1.1.2 Topography and Geology 2.2 GENERAL MANAGEMENT Proposed Article 4 1.1.3 General -

Download Brochure

2020 Your Holiday with Byways Short Cycling Breaks 4 Longer Cycling Breaks 7 Walking holidays 10 Walkers accommodation booking and luggage service 12 More Information 15 How Do I Book? 16 How Do I Get There? 16 The unspoilt, countryside of Wales, maps and directions highlighting things Shropshire and Cheshire is a lovely area to see and do along the way. We for cycling and walking. Discover move your luggage each day so you beautiful countryside, pretty villages, travel light, with just what you need for quiet rural lanes and footpaths, as well the day, and we are always just a as interesting places to visit and great phone call away if you need our help. pubs and tea shops. Customer feedback is very important With more than 20 years experience, we to us and our feedback continues to know the area inside-out. Our routes are be excellent, with almost everyone carefully planned so you explore the rating their holiday with us as best of the countryside, stay in the ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’. We are nicest places and eat good, local food. continuing to get many customers Holidays are self-led, so you have the returning for another holiday with us or freedom to explore at your own pace, recommending us to their friends. take detours stopping when and where Our Walkers’ Accommodation Booking you want. Routes are graded (gentle, and Luggage Service on the longer moderate or strenuous) and flexible - distance trail walks continues to be we can tailor holidays to suit specific very popular. Offa’s Dyke is always requirements - so there's something for busy as is the beautiful Pembrokeshire all ages and abilities. -

Local Plan Strategy Statement of Consultation (Regulation 22) C

PreSubmission Front green Hi ResPage 1 11/02/2014 14:11:51 Cheshire East Local Plan Local Plan Strategy Statement of Consultation (Regulation 22) C M Y CM MY CY May 2014 CMY K Chapters 1 Introduction 2 2 The Regulations 4 3 Core Strategy Issues and Options Paper (2010) 6 4 Place Shaping (2011) 11 5 Rural Issues (2011) 17 6 Minerals Issues Discussion Paper (2012) 21 7 Town Strategies Phase 1 (2012) 27 8 Wilmslow Vision (Town Strategies Phase 2) (2012) 30 9 Town Strategies Phase 3 (2012) 32 10 Development Strategy and Policy Principles (2013) 36 11 Possible Additional Sites (2013) 43 12 Pre-Submission Core Strategy and Non-Preferred Sites (2013) 46 13 Local Plan Strategy - Submission Version (2014) 52 14 Next Steps 58 Appendices A Consultation Stages 60 B List of Bodies and Persons Invited to Make Representations 63 C Pre-Submission Core Strategy Main Issues and Council's Responses 72 D Non-Preferred Sites Main Issues and Council's Reponses 80 E Local Plan Strategy - Submisson Version Main Issues 87 F Statement of Representations Procedure 90 G List of Media Coverage for All Stages 92 H Cheshire East Local Plan Strategy - Submission Version: List of Inadmissible Representations 103 Contents CHESHIRE EAST Local Plan Strategy Statement of Consultation (Reg 22): May 2014 1 1 Introduction 1.1 This Statement of Consultation sets out the details of publicity and consultation undertaken to prepare and inform the Cheshire East Local Plan Strategy. It sets out how the Local Planning Authority has complied with Regulations 18, 19, 20 and 22 of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning)(England) Regulations 2012 in the preparation of the Local Plan Strategy (formerly known as the Core Strategy). -

Wirral Archives Service Workshop Medieval Wirral (11Th to 15Th Centuries)

Wirral Archives Service Workshop Medieval Wirral (11th to 15th centuries) The Norman Conquest The Norman Conquest was followed by rebellions in the north. In the summer of 1069 Norman armies laid waste to Yorkshire and Northumbria, and then crossed the Pennines into Cheshire where a rebellion had broken out in the autumn – they devastated the eastern lowlands, especially Macclesfield, and then moved on to Chester, which was ‘greatly wasted’ according to Domesday Book – the number of houses paying tax had been reduced from 487 to 282 (by 42 per cent). The Wirral too has a line of wasted manors running through the middle of the peninsula. Frequently the tax valuations for 1086 in the Domesday Book are only a fraction of that for 1066. Castles After the occupation of Chester in 1070 William built a motte and bailey castle next to the city, which was rebuilt in stone in the twelfth century and became the major royal castle in the region. The walls of Chester were reconstructed in the twelfth century. Other castles were built across Cheshire, as military strongholds and as headquarters for local administration and the management of landed estates. Many were small and temporary motte and bailey castles, while the more important were rebuilt in stone, e.g. at Halton and Frodsham [?] . The castle at Shotwick, originally on the Dee estuary, protecting a quay which was an embarkation point for Ireland and a ford across the Dee sands. Beeston castle, built on a huge crag over the plain, was built in 1220 by the earl of Chester, Ranulf de Blondeville. -

Historic Towns of Cheshire

ImagesImages courtesycourtesy of:of: CatalystCheshire Science County Discovery Council Centre Chester CityCheshire Council County Archaeological Council Service EnglishCheshire Heritage and Chester Photographic Archives Library and The Grosvenor Museum,Local Studies Chester City Council EnglishIllustrations Heritage Photographic by Dai Owen Library Greenalls Group PLC Macclesfield Museums Trust The Middlewich Project Warrington Museums, Libraries and Archives Manors, HistoricMoats and Towns of Cheshire OrdnanceOrdnance Survey Survey StatementStatement ofof PurposePurpose Monasteries TheThe Ordnance Ordnance Survey Survey mapping mapping within within this this documentdocument is is provided provided by by Cheshire Cheshire County County CouncilCouncil under under licence licence from from the the Ordnance Ordnance Survey.Survey. It It is is intended intended to to show show the the distribution distribution HistoricMedieval towns ofof archaeological archaeological sites sites in in order order to to fulfil fulfil its its 84 publicpublic function function to to make make available available Council Council held held publicpublic domain domain information. information. Persons Persons viewing viewing thisthis mapping mapping should should contact contact Ordnance Ordnance Survey Survey CopyrightCopyright for for advice advice where where they they wish wish to to licencelicence Ordnance Ordnance Survey Survey mapping/map mapping/map data data forfor their their own own use. use. The The OS OS web web site site can can be be foundfound at at www.ordsvy.gov.uk www.ordsvy.gov.uk Historic Towns of Cheshire The Roman origin of the Some of Cheshire’s towns have centres of industry within a ancient city of Chester is well been in existence since Roman few decades. They include known, but there is also an times, changing and adapting Roman saltmaking settlements, amazing variety of other over hundreds of years. -

Reps1-9282-Ns-Bp

Representations on behalf of: Plant Developments Limited The Orchard, Holmes Chapel Road, Brereton Heath CHESHIRE EAST COUNCIL - PRE-SUBMISSION CORE STRATEGY (NOVEMBER 2013) EPP reference: REPS1-9282-NS-BP December 2013 Representations on behalf of: Plant Developments Limited The Orchard, Holmes Chapel Road, Brereton Heath Cheshire East Council - Pre-Submission Core Strategy (November 2013) 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Emery Planning Partnership is instructed on behalf of Plant Developments Ltd to make representations to Cheshire East Council’s Pre-Submission Core Strategy, which is currently out for consultation in relation to a site known as The Orchard, Holmes Chapel Road, Brereton Heath. 1.2 We submit that Brereton Heath should be identified in the DDS as a sustainable village/village cluster where appropriate levels of development should be allowed. 1.3 This statement accompanies our overall representations (EPP ref: REPS2-8032-JC-bp). 2. BACKGROUND Site location and description 2.1 The site is located on the south western side of the A54, Holmes Chapel Road. It comprises two bungalows on the road frontage with three large glass houses and outbuildings to the rear. A site location plan is attached at Appendix EPP1. Local Plan 2.2 The site is located within the open countryside. The majority of the site lies within the defined settlement of Brereton Heath. 2.3 Policies PS6 and H6 of the adopted Congleton Local Plan state that limited development will be permitted within the infill boundary line where it is appropriate to the local character in terms of use, intensity, scale and appearance and does not conflict with the other policies of the local plan. -

CHESHIRE. PUB 837 British Workman's Hall & Readingicongleton Masonic' (Joshua Hopkins, Queen's Ha~L (J

'1RaDES DIRECTORY.] CHESHIRE. PUB 837 British Workman's Hall & ReadingiCongleton Masonic' (Joshua Hopkins, Queen's Ha~l (J. G. B. Mawson, sec.), Room (John Green, manager),Grove caretaker), Mill st. Congleton 19 & 21 Claughton road, Birkenhead street, Wilmslow, Manchester Cong-leton Town (William Sproston, Runcorn Foresters' (Joseph Stubbs, Brunner Guildhall (Ellis Gatley, care- hall keeper), High st. Congleton sec.), Eridgewater street, Runcorn taker), St. John st. Runcorn Crewe Cheese, Earle street, Cre-we Runcorn Market ("William Garratt, Bunbury (Thomas Keeld, sec. to hall; Derby, .Argyle street, Birkenhead supt. ), Bridge street, Runcorn George F. Dutton, librarian), Bun- Frodsham 'fown(Linaker & Son, secs. ; Rnncorn Masonic Rooms (Richard bury, Tarporley Thomas Birtles, caretaker), Main st. Hannett, sec.),Bridgewater st.Rncrn Campbell Memorial (Chas. Edwards, Frodsham, Warrington Runcorn (.Arthnr Salkeld, sec.), caretaker), Boughton, Che~ter Gladstone Village (Alfred Rogers, Church street, Runcorn Chester Corn Exchange (Wakefield & keeper), Greendale road, Port Sun- Sale & Ashton-upon-Mersey Public Enock, agents), Eastgnte st.Chestet light, Birkenhead Hall Co. Limited (J. 0. Barrow, Chester Market (Henry Price, supt. ), Hyde Town, Market place, Hyde sec.), Ashton-upon-1\Iersey, M'chstr Northgate street, Chester Knutsford Market (Benjamin Hilkirk, Sandbach Town & Market(John Wood, Chester Masonic (Jn. Harold Doughty, keeper), Princess street, Knutsiord keeper), High street, Sandbach caretaker), Queen street, Chester :Macclesfield Town (Samuel Stone- Stalybridge Foresters', Vaudrey st. Chester Odd Fellows (Joseph Watkins, hewer, kpr.), l\Iarket pl.Macclesfield Stalybridge se~.), Odd Fellows' buildings, Lower Malpas (Matthew Henry Danily, hon. Stalybridge Odd Fellows' Hall & Social Bridge street, Chester . sec.; John W. Wycherley, Iibra- Club &; Institute (Levi Warrington, Chester Temperance(Jobn Wm.