The Devil We Already Know: Medieval Representations of a Powerless Satan in Modern American Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Reviews

Page 117 FILM REVIEWS Year of the Remake: The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man Jenny McDonnell The current trend for remakes of 1970s horror movies continued throughout 2006, with the release on 6 June of John Moore’s The Omen 666 (a sceneforscene reconstruction of Richard Donner’s 1976 The Omen) and the release on 1 September of Neil LaBute’s The Wicker Man (a reimagining of Robin Hardy’s 1973 film of the same name). In addition, audiences were treated to remakes of The Hills Have Eyes, Black Christmas (due Christmas 2006) and When a Stranger Calls (a film that had previously been ‘remade’ as the opening sequence of Scream). Finally, there was Pulse, a remake of the Japanese film Kairo, and another addition to the body of remakes of nonEnglish language horror films such as The Ring, The Grudge and Dark Water. Unsurprisingly, this slew of remakes has raised eyebrows and questions alike about Hollywood’s apparent inability to produce innovative material. As the remakes have mounted in recent years, from Planet of the Apes to King Kong, the cries have grown ever louder: Hollywood, it would appear, has run out of fresh ideas and has contributed to its evergrowing bank balance by quarrying the classics. Amid these accusations of Hollywood’s imaginative and moral bankruptcy to commercial ends in tampering with the films on which generations of cinephiles have been reared, it can prove difficult to keep a level head when viewing films like The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man. -

The Omen! BLOODY VALENTINES Exploitation Movie King John Dunning Interviewed!

THE DEVIL’S CHILD THE MAKinG OF THE Omen! BLOODY VALENTINES EXPLOitatiON MOvie KinG JOHN DunninG IntervieWED! MEDIEVAL MADNESS THE BLOOD On Satan’S SCARY MOVIE ClaW! ROUNDUP NEW DVDS and Blu-Rays DSD RevieWED! FREE! 06 Check out the teaser issue of CultTV Times... covering everything from NCIS to anime! Broadcast the news – the first full issue of Cult TV Times will be available to buy soon at Culttvtimes.com Follow us on : (@CultTVTimes) for the latest news and issue updates For subscription enquiries contact: [email protected] Introduction MACABRE MENU A WARM WELCOME TO THE 4 The omen 09 DVD LIBRARY 13 SUBS 14 SATAn’S CLAW DARKSIDe D I G I TA L 18 John DUnnIng contributing scripts it has to be good. I do think that Peter Capaldi is a fantastic choice for the new Doctor, especially if he uses the same language as he does in The Thick of It! Just got an early review disc in of the Blu-ray of Corruption, which is being released by Grindhouse USA in a region free edition. I have a bit of a vested interest in this one because I contributed liner notes and helped Grindhouse’s Bob Murawski find some of the interview subjects in the UK. It has taken some years to get this one in shops but the wait has been worthwhile because I can’t imagine how it could have been done better. I’ll be reviewing it at length in the next print issue, out in shops on October 24th. I really feel we’re on a roll with Dark Side at present. -

Birth and Ruin: Ttte Devil Versus Social Codes in Rosemary's Baby, the Exorcist and Ttie Omen

BIRTH AND RUIN: TTTE DEVIL VERSUS SOCIAL CODES IN ROSEMARY'S BABY, THE EXORCIST AND TTIE OMEN BY NATASHA LOPUSINA A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department ofEnglish University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba @ Natasha Lopusina, March 2005 THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES COPYRIGHT PERMISSION BIRTH AND RUIN: THE DEVIL VERSUS SOCIAL CODES IN ROSEMARY'S BABY, THE EXORCIST AND THE OMEN BY NATASHA LOPUSINA A ThesisÆracticum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree MÄSTER Of ARTS NATASHA LOPUSINA O 2OO5 Permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to University Microfilms Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright owner. Table of contents Abstract 2 Introduction J CHAPTER I. Rosemary's Baby - A Woman's Realþ Within a Lie t3 CHAPTER II. The Visual Terror of The Exorcist's Daughter 39 CHAPTER III. The Devil as The Omen of the American Family 66 Conclusion 94 Bibliography 103 Abstract In mv thesis Birth and Ruin: The Devil versus Social Codes in Rosemaryt's Bab\t. -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

Scared Sacred: Idolatry, Religion and Worship in the Horror Film Exclusive Chapter Except for Daily Dead From

Scared Sacred: Idolatry, Religion and Worship in the Horror Film Exclusive chapter except for Daily Dead from: “I don’t know if we’ve got the heir to the Thorn millions here or Jesus Christ Himself”: Catholicism, Satanism and the Role of Predestination in The Omen (1976) LMK Sheppard In The Omen’s (1976) climactic scene, protagonist Robert Thorn (Gregory Peck) takes his adoptive son Damien (Harvey Stephens) to sacred ground on the instruction of historian and demonologist/exorcist Carl Bugenhagen (Leo McKern). Thorn plans to murder the young heir in accordance with an ancient ritual. The entire narrative has led to this moment, at which point the titular omen is finally brought to bear: will the suspected Son of Satan be allowed to live, or will he be sacrificed for the greater good? This choice is not one made of free will; it has been purportedly predestined since biblical times, as confirmed by the final scene. At the double funeral of his parents, the camera focuses upon the face of Damien as he smiles before revealing that the child is holding the hands of two adults: Thorn’s best friends, the President of the United States and his first lady. Thorn’s attempt to kill Damien has set in motion a specific course of events, and the orphaned child has been adopted by arguably the most politically influential couple in the world. Thorn’s choice therefore played a pivotal part in the fulfillment of an ancient prophecy: the Antichrist will arise from the world of politics and bring about the apocalypse. -

Uses of the Bible in Contemporary Horror Films Mary Ann Beavis St

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha Journal of Religion & Film Volume 7 Article 2 Issue 2 October 2003 12-14-2016 "Angels Carrying Savage Weapons:" Uses of the Bible in Contemporary Horror Films Mary Ann Beavis St. Thomas More College, [email protected] Recommended Citation Beavis, Mary Ann (2016) ""Angels Carrying Savage Weapons:" Uses of the Bible in Contemporary Horror Films," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Angels Carrying Savage Weapons:" Uses of the Bible in Contemporary Horror Films Abstract As one of the great repositories of supernatural lore in Western culture, it is not surprising that the Bible is often featured in horror films. This paper will attempt to address this oversight by identifying, analyzing and classifying some uses of the Bible in horror films of the past quarter century. Some portrayals of the Bible which emerge from the examination of these films include: (1) the Bible as the divine word of truth with the power to drive away evil and banish fear; (2) the Bible as the source or inspiration of evil, obsession and insanity; (3) the Bible as the source of apocalyptic storylines; (4) the Bible as wrong or ineffectual; (5) the creation of non-existent apocrypha. -

Reconstructing the Death Star: Myth and Memory in the Star Wars Franchise

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-2018 Reconstructing the Death Star: Myth and Memory in the Star Wars Franchise Taylor Hamilton Arthur Katz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Katz, Taylor Hamilton Arthur, "Reconstructing the Death Star: Myth and Memory in the Star Wars Franchise" (2018). Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 91. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. ABSTRACT Mythic narratives exert a powerful influence over societies, and few mythic narratives carry as much weight in modern culture as the Star Wars franchise. Disney’s 2012 purchase of Lucasfilm opened the door for new films in the franchise. 2016’s Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, the second of these films, takes place in the fictional hours and minutes leading up to the events portrayed in 1977’s Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope. Changes to the fundamental myths underpinning the Star Wars narrative and the unique connection between these film have created important implications for the public memory of the original film. I examine these changes using Campbell’s hero’s journey and Lawrence and Jewett’s American monomyth. In this thesis I argue that Rogue One: A Star Wars Story was likely conceived as a means of updating the public memory of the original 1977 film. -

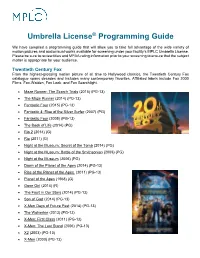

Programming Ideas

Umbrella License® Programming Guide We have compiled a programming guide that will allow you to take full advantage of the wide variety of motion pictures and audiovisual works available for screening under your facility’s MPLC Umbrella License. Please be sure to review titles and MPAA rating information prior to your screening to ensure that the subject matter is appropriate for your audience. Twentieth Century Fox From the highest-grossing motion picture of all time to Hollywood classics, the Twentieth Century Fox catalogue spans decades and includes many contemporary favorites. Affiliated labels include Fox 2000 Films, Fox-Walden, Fox Look, and Fox Searchlight. • Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials (2015) (PG-13) • The Maze Runner (2014) (PG-13) • Fantastic Four (2015) (PG-13) • Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) (PG) • Fantastic Four (2005) (PG-13) • The Book of Life (2014) (PG) • Rio 2 (2014) (G) • Rio (2011) (G) • Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014) (PG) • Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) (PG) • Night at the Museum (2006) (PG) • Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) (PG-13) • Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) (PG-13) • Planet of the Apes (1968) (G) • Gone Girl (2014) (R) • The Fault in Our Stars (2014) (PG-13) • Son of God (2014) (PG-13) • X-Men Days of Future Past (2014) (PG-13) • The Wolverine (2013) (PG-13) • X-Men: First Class (2011) (PG-13) • X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) (PG-13) • X2 (2003) (PG-13) • X-Men (2000) (PG-13) • 12 Years a Slave (2013) (R) • A Good Day to Die Hard (2013) -

Richard Donner Biography

COUNCIL FILE NO. 08- ~/)'1 COUNCIL DISTRICT NO. 13 APPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING DIRECT TO CITY COUNCIL The attached Council File may be processed directly to Council pursuant to the procedure approved June 26, 1990, (CF 83-1075-S1) without being referred to the Public Works Committee because the action on the file checked below is deemed to be routine and/or administrative in nature: _} A. Future Street Acceptance. _} B. Quitclaim of Easement(s). _} C. Dedication of Easement(s). _} D. Release of Restriction(s) . .20 E. Request for Star in Hollywood Walk of Fame. _} F. Brass Plaque(s) in San Pedro Sport Walk. _} G. Resolution to Vacate or Ordinance submitted in response to Council action. _} H. Approval of plans/specifications submitted by Los Angeles County Flood Control District. APPROVAL/DISAPPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING: APPROVED DISAPPROVED* ~. Council Office of the District V2· Public Works Committee Chairperson *DISAPPROVED FILES WILL BE REFERRED TO THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE. Please return to Council Index Section, Room 615 City Hall City Clerk Processing: Date notice and report copy mailed to interested parties advising of Council date for this item. Date scheduled in Council. AFTER COUNCIL ACTION: ----' Send copy of adopted report to the Real Estate Section, Development Services Division, Bureau of Engineering (Mail Stop No. 515) for further processing. ----' Other: PLEASE DO NOT DETACH THIS APPROVAL SHEET FROM THE COUNCIL FILE ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles, California To the Honorable Council SEP 2 4 2008 Ofthe City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C. -

2018 Television Report

2018 Television Report PHOTO: HBO / Insecure 6255 W. Sunset Blvd. CREDITS: 12th Floor Contributors: Hollywood, CA 90028 Adrian McDonald Corina Sandru Philip Sokoloski filmla.com Graphic Design: Shane Hirschman @FilmLA FilmLA Photography: Shutterstock FilmLAinc HBO ABC FOX TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 PRODUCTION OF LIVE-ACTION SCRIPTED SERIES 3 THE INFLUENCE OF DIGITAL STREAMING SERVICES 4 THE IMPACT OF CORD-CUTTING CONSUMERS 4 THE REALITY OF RISING PRODUCTION COSTS 5 NEW PROJECTS: PILOTS VS. STRAIGHT-TO-SERIES ORDERS 6 REMAKES, REBOOTS, REVIVALS—THE RIP VAN WINKLE EFFECT 8 SERIES PRODUCTION BY LOCATION 10 SERIES PRODUCTION BY EPISODE COUNT 10 FOCUS ON CALIFORNIA 11 NEW PROJECTS BY LOCATION 13 NEW PROJECTS BY DURATION 14 CONCLUSION 14 ABOUT THIS REPORT 15 INTRODUCTION It is rare to find someone who does not claim to have a favorite TV show. Whether one is a devotee of a long-running, time-tested procedural on basic cable, or a binge-watching cord-cutter glued to Hulu© on Sunday afternoons, for many of us, our television viewing habits are a part of who we are. But outside the industry where new television content is conceived and created, it is rare to pause and consider how television series are made, much less where this work is performed, and why, and by whom, and how much money is spent along the way. In this study we explore notable developments impacting the television industry and how those changes affect production levels in California and competing jurisdictions. Some of the trends we consider are: growth in the number of live-action scripted series in production, the influence of digital streaming services on this number, increasing production costs and a turn toward remakes and reboots and away from traditional pilot production. -

Super Heroes V Scorsese: a Marxist Reading of Alienation and the Political Unconscious in Blockbuster Superhero Film

Kutztown University Research Commons at Kutztown University Kutztown University Masters Theses Spring 5-10-2020 SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM David Eltz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/masterstheses Part of the Film Production Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Eltz, David, "SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM" (2020). Kutztown University Masters Theses. 1. https://research.library.kutztown.edu/masterstheses/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Research Commons at Kutztown University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kutztown University Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Research Commons at Kutztown University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Kutztown University of Pennsylvania Kutztown, Pennsylvania In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by David J. Eltz October, 2020 Approval Page Approved: (Date) (Adviser) (Date) (Chair, Department of English) (Date) (Dean, Graduate Studies) Abstract As superhero blockbusters continue to dominate the theatrical landscape, critical detractors of the genre have grown in number and authority. The most influential among them, Martin Scorsese, has been quoted as referring to Marvel films as “theme parks” rather than “cinema” (his own term for auteur film). -

Blu-Ray Titles

BLU-RAY DISC ASSOCIATION CES 2007 Blu-ray Disc: The Leader in HD Entertainment Current and Upcoming Title Releases∗ Currently Available 16 Blocks The Ant Bully 25th Anniversary: Live in Amsterdam The Architect 50 First Dates ATL Aeon Flux Basic Instinct 2 All the King’s Men Behind Enemy Lines America’s Soul Benchwarmers American Classic The Big Hit Annapolis Black Hawk Down Blazing Saddles Goal: The Dream Begins Blues Gone in 60 Seconds The Brothers Grimm Good Night and Good Luck Bubble The Great Raid The Covenant Haunted Mansion A Christmas Story HDNet World Report – Shuttle Club Date: Live in Memphis Discovery’s Historic Mission Crash Hitch Dark Water House of Flying Daggers The Descent House of Wax The Devil Wears Prada Ice Age: The Meltdown The Devil’s Rejects Into the Blue Dinosaur Invincible Eight Below The Italian Job Enemy of the State Jay & Silent Bob Strike Back Enron – The Smartest Guys in the Room John Legend – Live at the House of Fantastic Four Kingdom of Heaven Firewall Kiss Kiss Bang Bang The Fifth Element Kiss of the Dragon Flight of the Phoenix A Knight’s Tale Flightplan Kung Fu Hustle Four Brothers Lady in the Water Freak ‘N’Roll…Into the Fog The Lake House The Fugitive Lara Croft – Tomb Raider Full Metal Jacket The Last Samurai Glory Road The Last Waltz Go League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Lethal Weapon Space Cowboys Lethal Weapon 2 Species Little Man Speed Lord of War Stargate Memento Stealth Million Dollar Baby Stir of Echoes Mission-Impossible III Superman – The Movie Mission Impossible – Ultimate Missions Superman II – The Richard Donner Cut Collection Superman Returns Monster House S.W.A.T.