Harmony and Symmetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ireland P a R T O N E

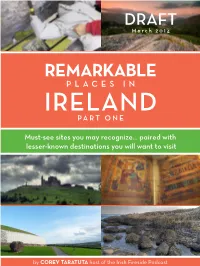

DRAFT M a r c h 2 0 1 4 REMARKABLE P L A C E S I N IRELAND P A R T O N E Must-see sites you may recognize... paired with lesser-known destinations you will want to visit by COREY TARATUTA host of the Irish Fireside Podcast Thanks for downloading! I hope you enjoy PART ONE of this digital journey around Ireland. Each page begins with one of the Emerald Isle’s most popular destinations which is then followed by several of my favorite, often-missed sites around the country. May it inspire your travels. Links to additional information are scattered throughout this book, look for BOLD text. www.IrishFireside.com Find out more about the © copyright Corey Taratuta 2014 photographers featured in this book on the photo credit page. You are welcome to share and give away this e-book. However, it may not be altered in any way. A very special thanks to all the friends, photographers, and members of the Irish Fireside community who helped make this e-book possible. All the information in this book is based on my personal experience or recommendations from people I trust. Through the years, some destinations in this book may have provided media discounts; however, this was not a factor in selecting content. Every effort has been made to provide accurate information; if you find details in need of updating, please email [email protected]. Places featured in PART ONE MAMORE GAP DUNLUCE GIANTS CAUSEWAY CASTLE INISHOWEN PENINSULA THE HOLESTONE DOWNPATRICK HEAD PARKES CASTLE CÉIDE FIELDS KILNASAGGART INSCRIBED STONE ACHILL ISLAND RATHCROGHAN SEVEN -

Program of the 76Th Annual Meeting

PROGRAM OF THE 76 TH ANNUAL MEETING March 30−April 3, 2011 Sacramento, California THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a forum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the organizers, not the Society. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 900 Second Street NE, Suite 12 Washington DC 20002-3560 USA Tel: +1 202/789-8200 Fax: +1 202/789-0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2011 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting 3 Contents 4................ Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5………..….2011 Award Recipients 11.................Maps of the Hyatt Regency Sacramento, Sheraton Grand Sacramento, and the Sacramento Convention Center 17 ................Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 18 ............... General Information . 20. .............. Featured Sessions 22 ............... Summary Schedule 26 ............... A Word about the Sessions 28…………. Student Events 29………..…Sessions At A Glance (NEW!) 37................ Program 169................SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 176................ Presidents of SAA . 176................ Annual Meeting Sites 178................ Exhibit Map 179................Exhibitor Directory 190................SAA Committees and Task Forces 194…….…….Index of Participants 4 Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting APRIL 1, 2011 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2010 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Margaret W. -

World Heritage Ireland

WORLD HERITAGE – IRELAND Ireland – A Country of Rich Heritage and Culture Front Cover photograph: Brú na Bóinne, Newgrange, Co. Meath Back Cover photograph: Skellig Michael 3 CONTENTS Heritage – What is it? 4 World Heritage and Ireland 4 How a property is nominated for World Heritage List status 5 Ireland’s World Heritage sites 6 Brú na Bóinne - The Archaeological Ensemble of the Bend of the Boyne 6 Skellig Michael 8 World Heritage Tentative List 9 Gallery of Tentative List Properties 12 Further information 14 4 HERITage – WHAT IS IT? Heritage is described by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) as “our legacy from the past, what we live with today and what we pass on to future generations”. Ireland is a country rich in heritage and culture and has long recognised the importance of preserving this for future generations. Our Irish culture and heritage has created the spirit and identity of our people throughout the world and makes us what we are today with our distinctive characteristics. WORLD HERITAGE AND IRELAND Ireland signed the UNESCO World Heritage Convention in 1991. This brings with it both opportunities and obligations; Ireland as the “State Party” commits to nominating examples of exceptional heritage sites to the World Heritage List and to manage and protect these sites sustainably into the future. A World Heritage Site is a property that has been inscribed onto the World Heritage List by the World Heritage Committee of UNESCO. Properties can be either of cultural or natural significance or a combination of the two (mixed). Cultural heritage refers to monuments, groups of buildings and sites with historical, aesthetic, archaeological, scientific, ethnological or anthropological value. -

Megaliths and Stelae in the Inner Basin of Tagus River: Santiago De Alcántara, Alconétar and Cañamero (Cáceres, Spain)

MEGALITHS AND STELAE IN THE INNER BASIN OF TAGUS RIVER: SANTIAGO DE ALCÁNTARA, ALCONÉTAR AND CAÑAMERO (CÁCERES, SPAIN) Primitiva BUENO RAMIREZ, Rodrigo de BALBÍN BEHRMANN, Rosa BARROSO BERMEJO Área de Prehistoria de la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares Enrique CERRILLO CUENCA CSIC, Instituto de Arqueología de Mérida Antonio GONZALEZ CORDERO, Alicia PRADA GALLARDO Archaeologist Abstract: Several projects on the megalithic sites in the basin of the river Tagus contribute evidences on the close relation between stelae with engraved weapons and chronologically advanced megalithic graves. The importance of human images in the development of Iberian megalithic art supports an evolution of these contents toward pieces with engraved weapons which dating back to the 3rd millennium cal BC. From the analysis of the evidences reported by the whole geographical sector, this paper is also aimed at determining if the graphic resources used in these stelae express any kind of identity. Visible stelae in barrows and chambers from the 3rd millennium cal BC would be the images around which sepulchral areas were progressively added, thus constituting true ancestral references throughout the Bronze Age. Keywords: Chalcolithic, megalithic sites, identities, metallurgy, SW Iberian Peninsula INTRODUCTION individuals along a constant course (Bueno et al. 2007a, 2008a) from the ideology of the earliest farmers (Bueno The several works on megalithic stelae we have et al. 2007b) to, practically, the Iron Age (Bueno et al. developed so far shape a methodological and theoretical 2005a, 2010). The similarity observed between this long base of analysis aimed at proving a strong symbolic course and the line of megalithic art is the soundest implementation current throughout the 3rd millennium cal reference to include the symbolic universe of these BC in SW Iberian Peninsula (Bueno 1990, 1995: Bueno visible anthropomorphic references in the ideological et al. -

Aerial Investigation and Mapping of the Newgrange Landscape, Brú Na Bóinne, Co

Aerial investigation and mapping of the Newgrange landscape, Brú na Bóinne, Co. Meath The Archaeology of the Brú na Bóinne World Heritage Site Interim Report, December 2018 This interim report has been prepared to make available the results of ongoing analysis, interpretation and mapping work in advance of full publication. The report has been produced for use on the internet. As such, the high-resolution imagery has been compressed to optimise downloading speeds. Interpretation and opinion expressed in the interim report are those of the authors. Printed copies of the report will be made available as soon as is practicable following the release of this digital version. Adjustments may be made to the final publication text subject to the availability of information at that time. NOTE Virtually all of the sites featured in this report are located on private land. These are working farms with both crops and livestock. There is no entry onto these lands without the express permission of the landowners. Furthermore, the sites are mostly subsurface and can only be seen as cropmarks. There are extensive views across the floodplain from Newgrange Passage Tomb, which can be accessed via the OPW Brú na Bóinne Visitor Centre. Details of on-line booking for the Brú na Bóinne Visitor Centre and guided tour of Newgrange are available at: http://www.heritageireland.ie/en/midlands-eastcoast/brunaboinnevisitorcentre/ Cover image: View across the Geometric Henge, looking north towards Newgrange Farm. © Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht -

Meath Heritage Trail 12/23/04 12:04 PM Page 1

Meath Heritage Trail 12/23/04 12:04 PM Page 1 Brú na Bóinne - Battle of the Boyne = 5km = Boyne the of Battle - Bóinne na Brú Slane - Brú na Bóinne na = 9km Brú - Slane Navan - Slane - Navan = 14km Oldcastle - Navan - = 38km Oldcastle Kells - Oldcastle - Kells = 22km Athboy - Kells - Athboy = 12km Trim - Athboy - Trim = 11km Bective - Trim Trim - Bective = 7km Tara - Bective Bective - Tara 5km = Heritage Trail Distances in km in Distances Trail Heritage own itinerary. own any point and plan your route to suit your suit to route your plan and point any Battle of the Boyne Site Boyne the of Battle 10 starting in Tara, you may start your trail at trail your start may you Tara, in starting While this trail follows a defined route defined a follows trail this While Brú na Bóinne na Brú 9 Kinnegad and continue on through Trim. through on continue and Kinnegad Slane 8 , take the N4 or the N6 to N6 the or N4 the take , From the West the From Navan 7 Cavan, Kells and Navan. and Kells Cavan, , take the N3 through N3 the take , From the North West North the From Oldcastle and Loughcrew and Oldcastle 6 or the N2 to Slane and on to Navan. to on and Slane to N2 the or Kells Heritage Town Heritage Kells 5 aeteM/1t Drogheda to M1/N1 the take , From the North the From Athboy 4 Slane and Navan. and Slane Mornington to Drogheda and on through on and Drogheda to Mornington Trim Heritage Town and Environs and Town Heritage Trim 3 to Laytown and Bettystown, on through on Bettystown, and Laytown to 2 Bective Abbey Bective to Meath. -

Ireland Through the Ages S Gustavus Adolphus College October 1 - 12, 2017Ire Ge Lan a College Ireland Through the Ages Hosted by Dr

Tour 4831 GAC Ireland Travel arrangements by Tour 4831 GAC Ireland Travel arrangements by Gustavus Adolphus College Ireland through the Ages I es Gustavus Adolphus College October 1 - 12, 2017re la g College Hosted by Dr. Kevin Byrne nd t e A us Ireland through the Ages hrough th ph , 2017 October 1 - 12, 2017 ol 1 - 12 Ad er Hosted by Dr. Kevin Byrne Sunday, October 1 MINNEAPOLIS-ST. PAUL DEPARTURE Gustavus tob Leave for Dublin via Atlanta on Delta Air Lines flight departing mid-afternoon . c O Sunday, October 1 MINNEAPOLIS-ST. PAUL DEPARTURE Leave for Dublin via Atlanta on Delta Air Lines flight departing mid-afternoon. Monday, October 2 DUBLIN ARRIVAL Tour 4831 GAC Ireland Morning arrival in Dublin. Welcome from awaiting IrishTravel tour arrangements manager by and a private motorcoach. Drive to North County Dublin for tea or coffee and homemade scones followed by a relaxing visit to Malahide Monday, October 2 DUBLIN ARRIVAL Morning arrival in Dublin. Welcome from awaiting Irish tour manager and a private motorcoach. Drive to Castle & Gardens, one of the oldest castles in Ireland. Enjoy a brief introduction to Ireland’s capital and a North County Dublin for tea or coffee and homemade scones followed by a relaxing visit to Malahide break for lunch on own en route to Ashling Hotel, for check-in and time to get settled for a three-night Castle & Gardens, one of the oldest castles in Ireland. Enjoy a brief introduction to Ireland’s capital and a stay. Group dinner at hotel. (D) Gustavus Adolphus College break for lunch on own en route to Ashling Hotel, for check-in and time to get settled for a three-night Ireland through the Ages stay. -

Memory and Monuments at the Hill of Tara

Memory and Monuments at the Hill of Tara Memory and Monuments at the Hill of Tara Erin McDonald This article focuses on the prehistoric monuments located at the ‘royal’ site of Tara in Meath, Ireland, and their significance throughout Irish prehistory. Many of the monuments built during later prehistory respect and avoid earlier constructions, suggesting a cultural memory of the site that lasted from the Neolithic into the Early Medieval period. Understanding the chronology of the various monuments is necessary for deciphering the palimpsest that makes up the landscape of Tara. Based on the reuse, placement and types of monuments at the Hill of Tara, it may be possible to speculate on the motivations and intentions of the prehistoric peoples who lived in the area. Institute for European and Mediterranean Archaeology 55 Erin McDonald This article focuses on the prehistoric and the work of the Discovery Programme, early historic monuments located at the relatively little was known about the ‘royal’ site of the Hill of Tara in County archaeology of Tara. Seán Ó Ríordáin Meath, Ireland, and the significance of the carried out excavations of Duma na nGiall monuments throughout and after the main and Ráith na Senad, but died before he period of prehistoric activity at Tara. The could publish his findings.6 In recent years, Hill of Tara is one of the four ‘royal’ sites Ó Ríordáin’s notes have been compiled from the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age into site reports and excavated material was in Ireland, and appears to have played an utilized for radiocarbon dating.7 important role in ritual and ceremonial activity, more so than the other ‘royal’ sites; medieval literature suggests that Tara had a crucial role in the inauguration of Irish kings.1 Many of the monuments built on the Hill of Tara during the later prehistoric period respect or incorporate earlier monuments, suggesting a cultural memory of the importance of the Hill of Tara that lasted from the Neolithic to the Early Medieval Period. -

Making Monuments Learn About Megalithic Tombs by Making Models

119 Module 6 Making Monuments Learn about megalithic tombs by making models Curriculum Linkages and Integration See Teacher Guidelines for additional information SESE History INFANT CLASSES 1st & 2nd CLASSES STRAND: Story STRAND: Change and continuity Strand Unit: Stories Strand Unit: Change and continuity in the local environment STRAND: Story Strand Unit: Stories 3rd & 4th CLASSES 5th & 6th CLASSES STRAND: Local Studies STRAND: Local Studies Strand Unit: Buildings, sites and ruins in my locality Strand Unit: Buildings, sites and ruins in my locality Strand Unit: My locality through the ages Strand Unit: My locality through the ages STRAND: Story STRAND: Story Strand Unit: Stories from the lives of people in the past Strand Unit: Stories from the lives of peoples in the past STRAND: Early peoples and ancient societies STRAND: Early peoples and ancient societies Strand Unit: Stone Age peoples Strand Unit: Stone Age peoples Strand Unit: Bronze Age peoples STRAND: Continuity and change over time Strand Unit: Homes and houses STRAND: Continuity and change over time Strand Unit: Homes and houses LINKAGES INTEGRATION SESE Geography Mathematics Visual Arts Drama - Human environments - Shape and space - Construction - Exploring and making drama - Natural environments - Early mathematical activities - Fabric and fibre - Co-operating and - Environmental awareness - Measures - Paint and colour communicating in making and care - Number drama - Data SESE Science SP&HE Gaeilge English - Energy and forces - Myself - Éisteacht - Receptiveness to language - Materials - Myself and others - Labhairt - Competence and confidence - Environmental awareness - Myself and the wider world - Scríbhneoireacht - Developing cognitive abilities and care - Léitheoireacht through language - Emotional and imaginative development through language “I made a tomb It was fun It was the Stone Age ” 2nd Class Pupil Module 6: Making Monuments 121 OBJECTIVE The pupils learn about megalithic tombs by making models of them in a sand tray. -

The Changing Face of Neolithic and Bronze Age Ireland: a Big Data Approach to the Settlement and Burial Records

The Changing Face of Neolithic and Bronze Age Ireland: A Big Data Approach to the Settlement and Burial Records McLaughlin, T., Whitehouse, N., Schulting, R. J., McClatchie, M., & Barratt, P. (2016). The Changing Face of Neolithic and Bronze Age Ireland: A Big Data Approach to the Settlement and Burial Records. Journal of World Prehistory. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-016-9093-0 Published in: Journal of World Prehistory Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

Brú Na Bóinne) World Heritage Site

Communicating World Heritage: Newgrange and the Bend of the Boyne (Brú na Bóinne) World Heritage Site Gabriel Cooney, UCD School of Archaeology University College Dublin Disclosure Specialist area of archaeological research – Neolithic period Member of steering committee for BnaB WHS management plan since 2013- representing ICOMOS Ireland Chaired steering committee for BnaB WHS Research Framework, Heritage Council, 2008-2009 Member, team led by Bright 3D, Boyne Valley Masterplan Dowth Lands, major private land holding (20% of WHS), research partnership with UCD School of Archaeology Expert member, International Committee on Archaeological Heritage Management (ICAHM), ICOMOS PERSONAL VIEW… Why Newgrange and Brú na Bóinne WHS as a case study? PHOTOS:NMS, DCHG Knowth Outstanding Universal Value • Criterion (i): The Brú na Bóinne monuments represent the largest expression of prehistoric megalithic rock art in Europe. • Criterion (iii): The concentration of social, economic and funerary monuments at this site and the long continuity of occupation or use from prehistory to the late medieval period make this one of the most significant archaeological sites in Europe. • Criterion (iv): The passage grave, here brought to its finest expression, was a feature of outstanding importance in prehistoric Europe and beyond. European Context Links with other megalithic WHS… Stonehenge and Avebury, Heart of Neolithic Orkney, Antequara (Spain), ….Carnac (France), candidate site •In a European context Ireland could be seen as under- represented in terms of WHS, but recognised internationally for the high quality of preservation of archaeological monuments and historic landscape character Irish Context Brú na Bóinne is the key site in the Irish World Heritage programme, central to the development of the programme The Heart of Neolithic Orkney WHS WHS and Buffer Zones (Historic Scotland, 2014, 5). -

Isbn 1 903570 21 2

ISBN 1 903570 21 2 Sources of further information Information about individual sites in Orkney (and Enquires about this Management Plan and how World anywhere else in Scotland): Heritage status affects monuments in Orkney should be http://www.rcahms.gov.uk directed to Dr Sally Foster (see below). http://www.scran.ac.uk For information on general World Heritage issues in Information about Historic Scotland: Scotland contact Malcolm Bangor-Jones of Historic http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk Scotland. Tel: 0131 668 8810. E-mail: [email protected] The local Sites and Monuments Record, maintained by the Orkney Archaeological Trust, is another source of Nomination of The Heart of Neolithic Orkney for inclusion information about individual sites and for advice on in the World Heritage List is available from Historic unscheduled monuments in general. Scotland (£10 plus p&p). For all Historic Scotland publications: Historic Scotland’s booklet, The Ancient Monuments of Telephone: 0131 668 8752. Orkney (£4.95, Historic Scotland) provides an accessi- E-mail: [email protected] ble introduction to the main archaeological visitor attractions on Orkney, including the WHS. A number of web sites can be accessed: See also Anna Ritchie’s Prehistoric Orkney and Patrick Ashmore’s Neolithic and Bronze Age Scotland Information about the WHS: (£15.99, Batsford/Historic Scotland). Official Souvenir http://www.unesco.org/whc/sites/514.htm Colour Guides exist for Maes Howe and Skara Brae (£2.50 each). Information on the World