Biopolitics and Belief in the Church of Christ, Scientist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De La Conversion À La Guérison Puritanisme, Psychothérapies, Développement Personnel

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense École doctorale Économie, Organisations, Société Laboratoire Sophiapol De la conversion à la guérison Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel Thèse Pour obtenir le grade de Docteur en sciences humaines et sociales, mention sociologie Soutenue le 29 mai 2013 par Pierre Prades Sous la direction d’Alain Caillé, professeur des uni@versités, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense Jury M. Hubert BOST, directeur de recherche, École Pratique des Hautes Études M. Alain CAILLÉ, professeur émérite, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense Mme Jacqueline CARROY, directeur d’études, École des Hautes Études en Sciences sociales M. Stéphane HABER, professeur des universités, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense Mme Roberte HAMAYON, directeur d’études, École Pratique des Hautes Études De la conversion à la guérison. Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel II De la conversion à la guérison. Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense École doctorale Économie, Organisations, Société Laboratoire Sophiapol De la conversion à la guérison Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel Pierre Prades 29 mai 2013 III De la conversion à la guérison. Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel IV De la conversion à la guérison. Puritanisme, psychothérapies, développement personnel À Brigitte, généreuse et patiente mécène, dont l’indulgente bienveillance m’a soutenu durant de si longues années, et sans laquelle je n’aurais pu ni entreprendre ni réaliser ce projet, À Jeanne, lectrice attentive et critique éclairée, À Louis, pour l’émulation, À mon père, avec le regret d’avoir tant tardé, et à ma mère, qui a attendu avec confiance. -

Downloadjune, 23, 2021 Ebulletin

June 23, 2021 - Changes Volume 21, No. 6 coU/chttp://members.christianscience.com/ Inspiration Theo11131111313 following excerpt #N13 is VVol “We11113.111311311#12 Knew Mary Baker Eddy, Expanded Edition, Vol.1” from Daisette D. S. McKenzie’s reminiscence. (pg. 254) The role of Reading Rooms While every Christian Scientist has the privilege of distributing these sacred writings, the opportunity of doing so in the appointed order belongs especially to our Reading Rooms and our Distribution Committees. Mrs. Eddy once spoke of “home” as “your calm, sacred retreat.” We may think of our Reading Rooms, too, as a spiritual home and sacred retreat for church members as well as for inquirers. In them is spread a banquet of sustaining food for the seeker after healing of mind and body. The doubting, the distressed, the bewildered, the weary, may find in the shelter of the Reading Room the quiet and peace in which to ponder and pray, and to gain direction from the intimate Love which is ever seeking to find that which is lost, to heal that which is broken, and to comfort “as one whom his mother comforteth” (Isaiah 66:13). Our Leader has provided in the Manual that no reading be done in a Reading Room except that of her writings, the Bible, and our authorized publications, and that secular matters not be discussed, that this atmosphere of calm and holy meditation may be always found there. May our church members realize more fully the purpose of the Reading Rooms and avail themselves more often of the tender care shown in providing them. -

A Measure of Detachment: Richard Hofstadter and the Progressive Historians

A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT: RICHARD HOFSTADTER AND THE PROGRESSIVE HISTORIANS A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS By Wiliiam McGeehan May 2018 Thesis Approvals: Harvey Neptune, Department of History Andrew Isenberg, Department of History ABSTRACT This thesis argues that Richard Hofstadter's innovations in historical method arose as a critical response to the Progressive historians, particularly to Charles Beard. Hofstadter's first two books were demonstrations of the inadequacy of Progressive methodology, while his third book (the Age of Reform) showed the potential of his new way of writing history. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................i CHAPTER 1. A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT..........................................................................1 2. SOCIAL DARWINISM IN AMERICAN THOUGHT………………………………………………26 3. THE AMERICAN POLITICAL TRADITION…………………………………………………………..52 4. THE AGE OF REFORM…………………………………………………………………………………….100 5. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………………………………139 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..144 CHAPTER ONE A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT Great thinkers often spend their early years in rebellion against the teachers from whom they have learned the most. Freud would say they live out a form of the Oedipal archetype, that son must murder his father at least a little bit if he is ever to become his own man. -

1. Universalist Churches—United States—History—18Th Century

The Universalist Movement in America 1770–1880 Recent titles in religion in america series Harry S. Stout, General Editor Saints in Exile Our Lady of the Exile The Holiness-Pentecostal Experience in Diasporic Religion at a Cuban Catholic African American Religion and Culture Shrine in Miami Cheryl J. Sanders Thomas A. Tweed Democratic Religion Taking Heaven by Storm Freedom, Authority, and Church Discipline Methodism and the Rise of Popular in the Baptist South, 1785–1900 Christianity in America Gregory A. Willis John H. Wigger The Soul of Development Encounters with God Biblical Christianity and Economic An Approach to the Theology of Transformation in Guatemala Jonathan Edwards Amy L. Sherman Michael J. McClymond The Viper on the Hearth Evangelicals and Science in Mormons, Myths, and the Historical Perspective Construction of Heresy Edited by David N. Livingstone, Terryl L. Givens D. G. Hart, and Mark A. Noll Sacred Companies Methodism and the Southern Mind, Organizational Aspects of Religion and 1770–1810 Religious Aspects of Organizations Cynthia Lynn Lyerly Edited by N. J. Demerath III, Princeton in the Nation’s Service Peter Dobkin Hall, Terry Schmitt, Religious Ideals and Educational Practice, and Rhys H. Williams 1868–1928 Mary Lyon and the Mount Holyoke P. C. Kemeny Missionaries Church People in the Struggle Amanda Porterfield The National Council of Churches and the Being There Black Freedom Movement, 1950–1970 Culture and Formation in Two James F. Findlay, Jr. Theological Schools Tenacious of Their Liberties Jackson W. Carroll, Barbara G. Wheeler, The Congregationalists in Daniel O. Aleshire, and Colonial Massachusetts Penny Long Marler James F. -

Christian Scientists in the Courts

Christianity Case Study – Minority in America 2018 Christian Scientists in the Courts Since independence, Christians have always been a majority of the US population, so it may seem curious to call American Christians a minority. However, some Christians have been rejected by the wider US Christian community and are thus “minoritized”—meaning they are treated as if they do not belong to the majority. Christians from such groups have often claimed they face persecution or hardships. One of these groups is the Christian Scientists. This American born The Mother Church of the Church of Christ, religion began in 1879 in Massachusetts, with Scientist, in Boston, Massachusetts. Photo by Rizka, teachings of Mary Baker Eddy, who wrote a book July 15, 2014. Wikimedia Commons: called Science and Health, which became a holy http://bit.ly/2s6MpcU. text to Christian Scientists along with the Bible. Note on this Case Study: The text describes the material world as an 1 illusion, and the real world as totally spiritual. Religions are embedded in culture, and are deeply impacted by questions of power. While Based in this belief, Christian Scientists generally reading this case study about Christianity and view disease and illness as a mental error, not a life as a member of a minority religion in America, think about who is in power and who physical problem. Thus, to heal ailments, they lacks power. Is someone being oppressed? Is usually rely on prayer rather than medical care. someone acting as an oppressor? How might When members get sick, they call for a “Christian religious people respond differently when they Science Practitioner”—a person certified by the are in a position of authority or in a position of Church, but with no medical credentials—to pray oppression? over them for healing in what believers call a As always, when thinking about religion and “treatment.” They usually refuse to vaccinate power, focus on how religion is internally their children, take medicine of any kind, or see a diverse, always evolving and changing, and doctor, even for emergencies. -

May 25, 2021 Volume 21, No. 5

May 25, 2021 - Changes Volume 21, No. 5 coU/chttp://members.christianscience.com/ Inspiration Theo11131111313 following excerpt #N13 is VVol from11113.111311311#12 “The importance of the Reading Room” by Richard Bergenheim (The Christian Science Journal, November 1994): Have you ever considered the fact that a Christian Science Reading Room exists to alert the community that human experience does not exist in a realm separate from God's government? A Reading Room can be thought of as the leaven of Truth and Love at work, permeating the neighborhood with a sense of Christ's new appearing, bringing healing and order to every aspect of human life. (Of course, it isn't the Reading Room that does this, but the prayer of those manning it and supporting it!) Christ, Truth, reveals that the human and the divine actually coincide. Jesus and later his disciples began their ministry by preaching ". the kingdom of God is at hand." The Reading Room is a place where this evangelical work continues within the world today. The belief that there is a disconnection between human experience and the Divine can result in much effort to establish a connection that already exists. Conscious being, like a pool produced by a spring, is the product of Soul, Spirit. The union between Soul and man is permanent and unalterable. The true nature and character of man are defined by Soul, God, who sustains man's existence. Consider the spring and the pool. If the spring stopped, the pool inevitably would go dry. The immortal activity of Soul prevents man from going dry. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

The Christian Science Hymnal, with Five Hymns Written by Reverend Mary Baker Eddy

The Christian Science hymnal, with five hymns written by Reverend Mary Baker Eddy. Boston, Mass., The Christian Science Publishing Society [1909 i.e. 1910] https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015056375143 Public Domain, Google-digitized http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google We have determined this work to be in the public domain, meaning that it is not subject to copyright. Users are free to copy, use, and redistribute the work in part or in whole. It is possible that current copyright holders, heirs or the estate of the authors of individual portions of the work, such as illustrations or photographs, assert copyrights over these portions. Depending on the nature of subsequent use that is made, additional rights may need to be obtained independently of anything we can address. The digital images and OCR of this work were produced by Google, Inc. (indicated by a watermark on each page in the PageTurner). Google requests that the images and OCR not be re-hosted, redistributed or used commercially. The images are provided for educational, scholarly, non-commercial purposes. CHRISTIAN SCIENCE HYMNAL Y THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE HYMNAL WITH FIVE HYMNS WRITTEN BY REVEREND MARY BAKER EDDY DISCOVERER AND FOUNDER OS CHRISTIAN SCIENCE PUBLISHEDBY THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE PUBLISHING SOCIETY FALMOUTH AND ST. PAUL STREETS BOSTON, U.S.A. Copyright, 1898, 1903, 1905 and 1909 by The Christian Science Board of Directors" BOSTON, MASS. All rights reserved. (Printed in U. S. A.) PREFACE TO THE 1910 EDITION OF THE HYMNAL. In presenting the 19 10 edition of the Hymnal, the Committee does not claim that all the hymns therein are strictly scientific, as the selection had to be made very largely from the writings of authors who were unacquainted with the teachings of Christian Science. -

Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications a Finding Aid

The Mary Baker Eddy Library Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications a finding aid mbelibrary.org [email protected] 200 Massachusetts Ave. Boston, MA 02115 617-450-7218 Collection Description Collection #: 11 MBE Collection Title: Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications Creator: Eddy, Mary Baker Inclusive Dates: 1856-1910, 1912 Extent: 15.25 __LF Provenance: Transferred from Mary Baker Eddy’s last home at Chestnut Hill (400 Beacon St.) on the following dates: August 26, 1932, June 1938, May 7, 1951, and April 1964. Copyright Materials in the collection are subject to applicable copyright laws. Restrictions: Scope and Content Note Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications consists of over 600 items chiefly from Mary Baker Eddy's files from her last residence at Chestnut Hill. All of the items in the collection were published during Eddy’s lifetime except "The Children’s Star" dated October 1912 (PE00030) and "A Funeral Sermon: Occasioned by the death of Mr. George Baker," 1679 (PE00109). Many of the items were annotated, marked, and requested by Eddy to be saved (see PE00055.033, PE00185-PE00189, PE00058.127). The collection consists of two series: Series I, Pamphlets and Series II, Serial Publications. Series I, Pamphlets, consists mostly of the writings of Mary Baker Eddy as small leaflets or booklets. The series also consists of writings by persons significant to the history of Christian Science (Edward A. Kimball, Bliss Knapp, Septimus J. Hanna, etc.). Some of the pamphlets were never published such as "Why is it?" by Mary Baker Eddy (PE00262). Pamphlets also include "Christ My Refuge" sheet music (PE00032) and a Science and Health advertisement (PE00220). -

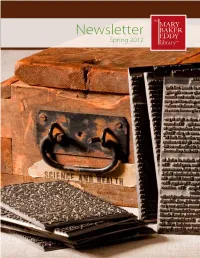

Newsletter Spring 2012 Contents

Newsletter Spring 2012 CoNteNtS contents4 3 Library NewS You’re invited! Library Open House New Exhibit Opens New Trustee on The Mary Baker Eddy Library Board Behind the Scenes: Curators in Action 7 CurreNt ProgramS First Saturday Events: Spring 2012 10 8 PaSt ProgramS April School Vacation Week Program Believing Young Voices Caring for Christmas & Charity Drive First Night 2012 Paths of Peace in Crisis February School Vacation Week Program 11 Author Talk: Keith Collins 13 ColleCtions From the Archives: Spotlight on Walter Watson From the Collection: Object of the Month 16 Noteworthy 15 17 DiD you kNow? 18 what’S New 19 ABOUT On the cover: Printing plates from the first edition of Science and Health. This image is from the new exhibit, Impressions on Paper: Mary Baker Eddy, Writer Library NewS A sampling of items displayed during last year’s event. You’re invited! Library Open House Join us on Sunday, June 3, from 11:30 a.m. to 1:45 p.m., to help kick off our 10 year anniversary celebration with a Library Open House. Staff from all depart- ments will be stationed throughout the building to introduce you to their work and share more about the Library’s collections, and through them, the history of Mary Baker Eddy and the Christian Science movement. On the third floor, don’t miss a special opportunity to hear the Curatorial staff highlight key treasures from our collections. Visitors will be encouraged to ask questions about these rarely-seen objects. On the fourth floor, Research & Reference Services will have items related to the “Busy Bees” on view as well as fascinating historical documents to read and ponder. -

775M Eh 7¢Ate¢

C opyright 1 962 R evision C o pyright 1 96 3 by Arthur C orey 5 X 5 7 4 5 £ 5 7 Prin ted in Th e Un ited States o f America MORE CLASS N OTES The L os Gatos - Saratoga class taught at my home, Casita Cresta, accommodated but a minor fraction of the applicants . Thus it seemed a happy fortuity when substantial notes taken of that an aly tical exploration of applied metaphysics were made available to me afterward . Their publication in 1956 n o t only provided review materials for those who came from various parts of the field for the n e eve t, but it enabled the absent stud nts to share, in . at least some measure, in the undertaking Now, with this greatly enlarged edition of the orig inal pamphlet it is possible to include additional material found useful by the many who attended the San Francisco class later on . The present paper does not purport to be a com n o r prehensive restatement of either course, can it be regarded as a rounded presentation o f even the bare essentials . Nevertheless, however fragmentary it may be it does cover some of the cardinal points made, points which the students generally felt should be made a part of the permanent record for s u continuing t dy . It is a commonplace that class notes are seldom r r ve y accu ate . That does not mean they are worth less . On the contrary, every veteran Scientist can o ut testify, as Bicknell Young pointed to his pupils, that such n otes can on occasion prove priceless . -

Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women As Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860 Kim M

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Western Washington University Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2017 More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860 Kim M. (Kim Michaelle) Davidson Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Davidson, Kim M. (Kim Michaelle), "More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860" (2017). WWU Graduate School Collection. 558. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/558 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans 1830-1860 By Kim Michaelle Davidson Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Jared Hardesty Dr. Hunter Price Dr. Holly Folk MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU.