Murray Moss-Design Impresario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Information New University of the Arts London Campus Central Saint Martins at King’S Cross

Media Information © 2011 New University of the Arts London Campus Central Saint Martins at King’s Cross Project Description October 2011 To the north of King’s Cross and St Pancras International railway stations, 67-acres of derelict land are being transformed in what is one of Europe’s largest urban regeneration projects. The result will be a vibrant mixed-use quarter, at the physical and creative heart of which will be the new University of the Arts London campus, home of Central Saint Martins College of Arts and Design. Stanton Williams’ design for the £200m new campus unites the college’s activities under one roof for the first time. It provides Central Saint Martins with a substantial new building, connected at its southern end to the Granary Building, a rugged survivor of the area’s industrial past. The result is a state-of-the-art facility that not only functions as a practical solution to the college’s needs but also aims to stimulate creativity, dialogue and student collaboration. A stage for transformation, a framework of flexible spaces that can be orchestrated and transformed over time by staff and students where new interactions and interventions, chance and experimentation can create that slip-steam between disciplines, enhancing the student experience. The coming together of all the schools of Central Saint Martins will open up that potential. The design aims to maximise the connections between departments within the building, with student and material movement being considered 3-dimensionally, as a flow diagram North to South, East to West, and up and down – similar in many ways to how the grain was distributed around the site using wagons and turntables. -

Pictorial Modernism PICTORIAL MONDERNISM

ANM102 | HISTORY OF GRAPHIC AND WEB DESIGN CHAPTER 14 Pictorial Modernism PICTORIAL MONDERNISM The Beggarstaffs • Brothers-on-law, James Pryde and William Nicholson opened an advertising design studio in 1894 and to protect their reputations as fine artists, they named it The Beggarstaff Brothers. They developed a new technique that was later called collage. By cutting pieces of paper, moving them around and pasting in position on a board, they created flat plans of color where the edges of the shapes were “drawn” with scissors. • Unlike Art Nouveau, the Beggarstaffs forged a new beginning of design focused on powerful colored shapes and silhouettes rather than organic and decorative form. PICTORIAL MODERNISM 2 PICTORIAL MONDERNISM Poster Design in Europe • The European poster in the first half of the 20th century was greatly influenced by the modern-art movements surrealism, cubism, and dadaism. Designers were aware of the need to use pictorial references in their posters as a way to visually enhance and ultimately communicate more persuasively their views. Influenced mostly by cubism and constructivism, poster artists combined expressive and symbolic images as well as total visual organization on the picture plane. William Pickering, title page for the Book of Common Prayer, 1844. PICTORIAL MODERNISM 3 POSTER DESIGN The Beggarstaffs • poster for Harper’s Magazine, 1895 PICTORIAL MODERNISM 4 POSTER DESIGN The Beggarstaffs • poster for Don Quixote, 1896 • never printed because the director/producer of the play felt the image was a bad likeness of Quixote. PICTORIAL MODERNISM 5 POSTER DESIGN Dudley Hardy • British painter who joined The Beggarstaffs in creating posters and advertising design • Theatrical poster for The Gaiety Girl, 1898 • Developed a formula for theatre poster design where letters and images appeared on a flat plane of color PICTORIAL MODERNISM 6 PICTORIAL MONDERNISM Plakastijl • A design school originating in Germany— the name means “poster style.” • The traits of Plakastijl are usually bold, straight lettering with a very simple design. -

Versidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Unidad Azcapotzalco

Este material tiene fines pedagógicos y su función es servir como apoyo en las prácticas educativas que se llevan a cabo en las licenciaturas que se imparten en la División de Ciencias y Artes para el Diseño de la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, unidad Azcapotzalco. En este sentido, el único fin de esta obra es generar y compartir material de apoyo para el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje en el campo del diseño. Asimismo, el autor de esta presentación es responsable de todo su contenido y la obra se encuentra protegida bajo una licencia de Creative Commons 4.0. Para más información se puede consultar el sitio https://creativecommons.org/. Escuela tipográfica alemana del estilo gótico hasta nuestros días Apoyo A lA UEA Clave UEA: 1424013 Nombre UEA: Temas Selectos de Tipografía Clave UEA 1423014 Nombre UEA: Teoría y metodología Aplicada I (Apoyo a Diseño de Mensajes Gráficos) Guión argumental Revisar los tipógrafos e impresores clave de la escuela alemana del estilo gótico hasta nuestros días y su influencia en desarrollo de la forma tipográfica en el pasado a la actualidad. Escuela tipográfica alemana del estilo gótico hasta nuestros días Alfonso García Reyes 1 Escuela tipográfica alemana del estilo gótico hasta nuestros días Objetivo Conocer las generalidades y los momentos clave de la historia de la tipográfica alemana desde el estilo gótico hasta la fecha, desarrollando criterios propios para asociar forma y producción al contexto histórico y su aplicación. Desarrollar una apreciación de los diversos estilos históricos alemanes desde el estilo gótico a la fecha, y como estos sirvieron de base para formar criterios, encontrar el estilos tipográficos apropiados para proyectos de diseño e interpretar un nuevo estilo tipográfico con las herramientas digitales. -

Habitat Ltd, Furniture and Household Goods Manufacturer and Retailer: Records, Ca

V&A Archive of Art and Design Habitat Ltd, furniture and household goods manufacturer and retailer: records, ca. 1960 – 2000 1 Table of Contents Introduction and summary description ................................................................ Page 4 Context .......................................................................................................... Page 4 Scope and content ....................................................................................... Page 4 Provenance ................................................................................................... Page 5 Access ......................................................................................................... Page 5 Related material .......................................................................................... Page 5 Detailed catalogue ................................................................................ Page 6 Corporate records .............................................................................................. Page 6 Offer for sale by tender, 1981 ................................................................................................ Page 6 Annual Reports and Accounts, 1965-1986 ............................................................................. Page 6 Marketing and public relations records ............................................................. Page 7 Advertising records, 1966-1996 ............................................................................................ -

A Teaching Innovation on Retail Environmental Design for Consumers with Disabilities

A Teaching Innovation on Retail Environmental Design for Consumers with Disabilities Meng-Hsien (Jenny) Lin, William J. Jones, and Akshaya Vijayalakshmi Purpose of Study: A teaching innovation that bridges the gap identified in current retailing textbooks, which pay minimal attention to serving consumers with disabilities in the marketplace, is proposed and assessed. This retail class project considers not only the legal and profit benefits for the firm, but also the inclusion and sense of normalcy for a consumer from a societal marketing perspective. Method/Design and Sample: Forty-one students working on the retail project were invited to participate in a pre- and post- test survey that investigates 1) their knowledge of disability regulations and accommodations required of retail outlets and 2) the usefulness of the project in advancing their careers and academic learning. In addition to the use of a “cognitive walkthrough” method of data collection for the class project, students were introduced to the concepts and model of servicescape and consumer normalcy in preparation for the project. Results: Results indicated that learning objectives were met and student expectations were achieved through the implementation of the retail project. Value to Marketing Educators: The implications of considering consumers with disabilities in retail environmental design includes: the physical needs of adapting to consumers with disabilities and the psychological need of consumers wanting to be included and perceived as “normal.” The innovation extends students’ learning about consumers with disabilities while reinforcing traditional retail concepts, such as store layout, visual merchandising, consumer behavior, and the notion of a servicescape. The project is adaptable to various marketing courses. -

Hajo Christoph Papers MG

A Guide to the Hajo Christoph Papers Collection Summary Collection Title: Hajo Christoph Papers Call Number: MG-195 Creator: Hajo Christoph Inclusive Dates: June 28,1926 - May 27, 1977 Bulk Dates: Abstract: Materials relating to the activities of Hajo Christoph, specifically his time working for the Fort Orange Paper Company designing graphic designs, and time spent as a member of the Albany Artists Group. Quantity: 2 linear feet Administrative Information Custodial History: Donated as a gift by Peter and Flo Christoph Preferred Citation: Hajo Christoph Papers. Albany Institute of History & Art Library, New York. Acquisition Information: Accession #: Accession Date: Processing Information: Processed by Brendan Peabody; completed on March 2, 2010. Restrictions Restrictions on Access: None Restrictions on Use: Permission to publish material must be obtained in writing prior to publication from the Chief Librarian & Archivist, Albany Institute of History & Art, 125 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY 12210. Index Term Persons Bernhard, Lucian (04/15/1883-05/29/1972) Brashear, Peter C. (1868-1943) Corning, Erastus 2nd (1909-1983) Justus, Donald C. (Mayor of Castleton on Hudson in 1970’s) Latham, William G. (1896 -1953) Organizations Fort Orange Paper Company- Castleton on the Hudson (N.Y.) Embossing Company of Albany Albany Artists Group Subjects Commerce-Advertising Fine Arts-Commercial Art Fine Arts- Advertising Art Fine Arts-Visual Arts-Exhibitions Immigration Industry-Manufacturing Industries Places Berlin (Germany) Castleton on Hudson (N.Y.) New York (N.Y.) Document Types Awards Photographs Correspondences License Memoir Newspaper Articles Magazine Articles Catalogs Certificates Programs Titles Biography of Hajo Christoph Hajo is not his actual birth name, but rather it is used as a trademark for his graphic designs. -

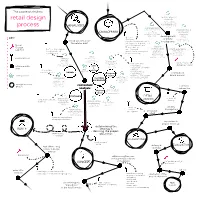

Retail Design Process

The course of a holistic spatial / physical retail design elements lay-out / routing sight-lines / focus points product placement / VM process ANALYSIS interior & exterior shell communication furniture in-store communication organisational & logo DEVELOPMENT corporate identity operational external communication elements digital content development service KEY: - sketches personel - 2D & plans of all the distribution/logistics critical assessment of - capacity / product placement touchpoints check-out process the retailer brief - wireframes (web, mobile, etc.) Retail - levels of communication digital & Design - 3D & renderings Lab tool - Kapferer - brand prism - material board technological brand experience - brand moodboard elements design language - models / rapid prototyping storytelling - brand pyramid website / webshop - virtual technology payment system functional components data-technology sensory elements offer communication methods practical tool identity products & services personality characteristics brand values VM & presentation “status quo” direct competitors tone of voice - trendwatchers - sense matrix image / visual identity start-ups - design guidelines intermediate history offer retail-, and - retail safari step & consumer trends - magazines / academic - Osterwalder staff service literature operational - benchmarking bussiness model BRAND needs unexpected - SWOT-analysis conceptbook component factor - Porter (5 forces model) brand manual next step...? - positioning diagram organisation IN-STORE how to create staff difference, -

Jaarverslag 2019 Voorwoord

JAARVERSLAG 2019 VOORWOORD Een jaar vol opwinding Het afgelopen jaar was voor Design Museum Den Bosch een De grote tentoonstelling Design van het Derde Rijk opende net periode vol opwinding en nieuwe ervaringen. Natuurlijk wordt na de zomer en riep al bij de eerste aankondiging de nodige onze terugblik bepaald door alles wat we meemaakten met de reacties in de pers op zodat deze daarna voortdurend nieuws en tentoonstelling Design van het Derde Rijk. Maar laten we bij het dus publiciteit genereerde. Gedurende de zomer bereidde het begin van het jaar beginnen. De tentoonstelling Jean Cocteau - museum zich voor op een grote toeloop en nam maatregelen op Metamorphosis die in het najaar van 2018 verwachtingsvol aan- het gebied van veiligheid en publieksontvangst, onder meer door ving, liep nog geruime tijd door in 2019 en de bezoekersaantallen een intensief educatief programma. De gevoeligheid van het on- groeiden per week. Dit was voor het museum de bevestiging dat derwerp bracht met zich mee dat, zeker naarmate de openings- het werk van modern klassieke kunstenaars en ontwerpers uit datum naderde, sprake was van fikse publieke discussies. De onze collectie op grote belangstelling kan rekenen, zeker als het aanvankelijke commotie waaide echter snel over, toen de eerste bekeken wordt vanuit een hedendaags en verfrist perspectief. bezoekers de tentoonstelling hadden bekeken, en sloeg meteen om in grote waardering. De internationale pers sprak zich en Het museum kiest er steeds nadrukkelijker voor om ook op de masse positief over de tentoonstelling uit en onze verwachtingen kleinere, tweede verdieping tentoonstellingen met ambitie te over de publieke belangstelling moesten per dag naar boven programmeren. -

A Chair to Look to the Moon What We Can Learn from Irrational Design History for Contemporary Design Practice

Paper draft – for DesignIX conference in Berlin, 15-17 februari. Version 10 November 2008 A chair to look to the moon What we can learn from irrational design history for contemporary design practice. Introduction The focus of product design is shifting from primarily offering functionality, towards experience and emotion driven product characteristics (Green, 2002). According to the theory of product phases (Eger, 2007), products will end in a phase characterized by individualization or awareness. Where the affective, emotional and abstract product values, become more and more important (Desmet, 2002; Norman, 2004). Individualization and awareness are, not accidently, also high up in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Different authors have different ideas about how to implement this emotion and affection in product design. Some of them even argue that affectivity is not influenced by the design at all, but only through the meaning that the user attaches to the product (Csikszentmihalyi, 1991/2007). That this idea is not new, or even from the last decades, is illustrated by a Chinese chair design dating from the Ming-period (illustration 1). This chair type is referred to as a ‘chair to look to the moon’ instead of as a ‘reclining chair’. In this way the chair is defined by the thing that you have to do with it, rather than by its functioning. And with this title the design opens up a whole of poetic associations like quiet nights on a veranda, clear skies, twinkling stars or even howling werewolves. By dreaming away with these associations you might even forget that the chair is actually not very comfortable. -

Statement on Social Safety in Art Education 20 May 2021

Statement on Social Safety in Art Education 20 May 2021 In the KUO Sector Agenda 2021-2025, social safety is explicitly named as a theme.1 It is clear that the sector considers social safety a crucial issue and we have decided to elaborate on this theme in a joint approach. This is informed in part by the attention recently paid to various issues of social safety. In this context, studies have been carried out, discussions held, conclusions drawn and policies and procedures reviewed at various art schools. The sector takes a critical look at itself and takes steps where necessary. This statement and the accompanying ‘outline of the social safety code’ are the next step in that process, a joint step that we are taking as a sector. As an art education sector, we wish to send out a clear joint signal. A signal that shows that the sector is aware that social safety is not an ad-hoc matter but requires constant attention. And that social safety consists of various facets and therefore forms an integral part of our organisations and of the dialogue. In addition to the existing approach at the various art schools, a follow-up step is therefore now being taken in which we work together. In art education, everyone should be able to work and study in a good and professional atmosphere that is safe and transparent, both in teaching and in research. It is crystal clear that undesirable behaviour such as bullying, discrimination, intimidation, sexual harassment, aggression, violence and other forms of transgressive behaviour are unacceptable and must be prevented. -

Retail Design Guidelines V5

DRAFT Design and Development Controls - Interiors Part 3 V5 It’s part Retail Design Guidelines of our Monash Masterplan Buildings and Property Division I January 2018 Contents The Design and Development Part 1 - Overview Controls - Interiors is a Part 2 - Signage Palette document that is divided into Part 3 - Retail Design Guidelines standalone sections that at Part 4 - Retail Signage Guidelines each project stage - feasibility, briefing, procurement, construction, ongoing and operation and management - consulting designers can be referred to connect with Monash’s overarching ambitions and principles that promote and advise on good design. The four sections enable users to access the information contained in the document to suit their requirements. Smaller and/or less complex projects may only require information contained within the overview, and minimal sections, whilst larger and/or more complex projects may require referencing to the document in its entirety. It’s part Authors of our Monash Campus Design, Quality and Planing, Masterplan Buildings and Property Division, Monash University It’s part of our Monash Masterplan Design and Development Controls - Interiors | Overview Page 2 Preface Interior spaces are the fabric of Monash Sitting within the Buildings and University campus experiences. They Property Division of Monash provide environments for teaching, University the Campus Design, learning and engagement; and influence Quality and Planning(CDQP) team provides strategic people’s experiences of it’s campuses. guidance and advice to designers to affect the To ensure spatial “outcomes will be architecture and design of distinguished yet welcoming, internal and exterior spaces on Monash University campuses contemporary yet enduring, flexible yet in Australia. -

Department Stores on Sale: an Antitrust Quandary Mark D

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 1 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary Mark D. Bauer Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark D. Bauer, Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bauer: Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary DEPARTMENT STORES ON SALE: AN ANTITRUST QUANDARY Mark D. BauerBauer*• INTRODUCTION Department stores occupy a unique role in American society. With memories of trips to see Santa Claus, Christmas window displays, holiday parades or Fourth of July fIreworks,fireworks, department storesstores- particularly the old downtown stores-are often more likely to courthouse.' engender civic pride than a city hall building or a courthouse. I Department store companies have traditionally been among the strongest contributors to local civic charities, such as museums or symphonies. In many towns, the department store is the primary downtown activity generator and an important focus of urban renewal plans. The closing of a department store is generally considered a devastating blow to a downtown, or even to a suburban shopping mall. Many people feel connected to and vested in their hometown department store.