Ladder of Abstraction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI Project, Nigeria

l- World Health Organization African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control FINAL RËPOftî ,i ={ Evaluation of the Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI Project, Nigeria N ove m ber- Decem ber 2004 Elizabeth Elhassan (Team Leader) Uwem Ekpo Paul Kolo William Kisoka Abraraw Tefaye Hilary Adie f'Ï 'rt\ t- I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I Table of contents............. ..........2 Abbreviations/Acronyms ................ ........ 3 Acknowledgements .................4 Executive Summary .................5 *? 1. lntroduction ...........8 2. Methodology .........9 2.1 Sampling ......9 2.2 Levels and lnstruments ..............10 2.3 Protocol ......10 2.4 Team Composition ........... ..........11 2.5 Advocacy Visits and 'Feedback/Planning' Meetings........ ..........12 2.6 Limitations ..................12 3. Major Findings And Recommendations ........ .................. 13 3.1 State Level .....13 3.2 Local Government Area Level ........21 3.3 Front Line Health Facility Level ......27 3.4 Community Level .............. .............32 4. Conclusions ..........36 4.1 Grading the Overall Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI project.................36 4.2 Grading the Project as a whole .......39 ANNEXES .................40 lnterviews ..............40 Schedule for the Evaluation and Advocacy.......... .................42 Feedback and Planning Meetings, Agenda.............. .............44 Report of the Feedbacl</Planning Meetings ..........48 Strengths And Weaknesses Of The Niger State Cdti Project .. .. ..... 52 Participants Attendance List .......57 Abbrevi -

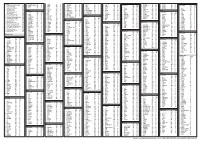

LGA Agale Agwara Bida Borgu Bosso Chanchaga Edati Gbako Gurara

LGA Agale Agwara Bida Borgu Bosso Chanchaga Edati Gbako Gurara Katcha Kontagora Lapai Lavun Magama Mariga Mashegu Mokwa Munya Paikoro Rafi Rijau Shiroro Suleja Tafa Wushishi PVC PICKUP ADDRESS Santali Road, After Lga Secretariat, Agaie Opposite Police Station, Along Agwara-Borgu Road, Agwara Lga Umaru Magajib Ward, Yahayas, Dangana Way, Bida Lga Borgu Lga New Bussa, Niger Along Leg Road, Opp. Baband Abo Primary/Junior Secondary Schoo, Near Divisional Police Station, Maikunkele, Bosso Lga Along Niger State Houseso Assembly Quarters, Western Byepass, Minna Opposite Local Govt. Secretariat Road Edati Lga, Edati Along Bida-Zungeru Road, Gbako Lga, Lemu Gwadene Primary School, Gawu Babangida Gangiarea, Along Loga Secretariat, Katcha Katcha Lga Near Hamdala Motors, Along Kontagora-Yauri Road, Kontagoa Along Minna Road, Beside Pension Office, Lapai Opposite Plice Station, Along Bida-Mokwa Road, Lavun Off Lga Secretariat Road, Magama Lga, Nasko Unguwan Sarki, Opposite Central Mosque Bangi Adogu, Near Adogu Primary School, Mashegu Off Agric Road, Mokwa Lga Munya Lga, Sabon Bari Sarkin Pawa Along Old Abuja Road, Adjacent Uk Bello Primary School, Paikoro Behind Police Barracks, Along Lagos-Kaduna Road, Rafi Lga, Kagara Dirin-Daji/Tungan Magajiya Road, Junction, Rijau Anguwan Chika- Kuta, Near Lag Secretariat, Gussoroo Road, Kuta Along Suleja Minna Road, Opp. Suleman Barau Technical Collage, Kwamba Beside The Div. Off. Station, Along Kaduna-Abuja Express Road, Sabo-Wuse, Tafa Lga Women Centre, Behind Magistration Court, Along Lemu-Gida Road, Wushishi. Along Leg Road, Opp. Baband Abo Primary/Junior Secondary Schoo, Near Divisional Police Station, Maikunkele, Bosso Lga. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

International Journal of Language, Literature and Gender Studies (LALIGENS), Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol

1 LALIGENS, VOL. 8(2), S/N 18, AUGUST/SEPT., 2019 International Journal of Language, Literature and Gender Studies (LALIGENS), Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol. 8 (2), Serial No 18, August/Sept., 2019:1-12 ISSN: 2225-8604(Print) ISSN 2227-5460 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/laligens.v8i2.1 BABEL OF NIGER STATE 1IHENACHO, A. A., JAMIU, A. M., AGU, M. N., EBINE, S. A., ADELABU, S. & OBI, E. F. Faculty of Languages and Communication Studies IBB University, Lapai, Niger State, Nigeria 1+2348127189382 [email protected] Abstract This paper is a preliminary report on an ongoing research being carried out in the Faculty of Languages and Communication Studies of Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University, Lapai, Niger State, Nigeria. The research is on ‘Language education and translation in Niger State’. The languages involved in the research are: Arabic, English, French, Gbagyi, Hausa and Nupe. The aim of this research which is funded by the Nigerian Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFund) is ‘to help improve the outcome of language education and translation in Niger State in both quality and quantity’ As a preliminary inquiry, the research team visited 78 institutions of learning at all levels (primary, secondary and tertiary) in all the three geopolitical zones of Niger State, as well as media houses located in the capital, Minna, and obtained responses to the questionnaires they took to the institutions. While pursuing the aim and objectives of their main research, the team deemed it necessary to consider the position (and the plight) of the multiplicity of other languages of Niger State (than the three major ones – Gbagyi, Hausa and Nupe) in relation to Nigeria’s language policy in education. -

Facts and Figures About Niger State Table of Content

FACTS AND FIGURES ABOUT NIGER STATE TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE DESCRIPTION PAGE Map of Niger State…………………………………………….................... i Table of Content ……………………………………………...................... ii-iii Brief Note on Niger State ………………………………………................... iv-vii 1. Local Govt. Areas in Niger State their Headquarters, Land Area, Population & Population Density……………………................... 1 2. List of Wards in Local Government Areas of Niger State ………..…... 2-4 3. Population of Niger State by Sex and Local Govt. Area: 2006 Census... 5 4. Political Leadership in Niger State: 1976 to Date………………............ 6 5. Deputy Governors in Niger State: 1976 to Date……………………...... 6 6. Niger State Executive Council As at December 2011…........................ 7 7. Elected Senate Members from Niger State by Zone: 2011…........…... 8 8. Elected House of Representatives’ Members from Niger State by Constituency: 2011…........…...………………………… ……..……. 8 9. Niger State Legislative Council: 2011……..........………………….......... 9 10. Special Advisers to the Chief Servant, Executive Governor Niger State as at December 2011........…………………………………...... 10 11. SMG/SSG and Heads of Service in Niger State 1976 to Date….….......... 11 12. Roll-Call of Permanent Secretaries as at December 2011..….………...... 12 13. Elected Local Govt. Chairmen in Niger State as at December 2011............. 13 14. Emirs in Niger State by their Designation, Domain & LGAs in the Emirate.…………………….…………………………..................................14 15. Approximate Distance of Local Government Headquarters from Minna (the State Capital) in Kms……………….................................................. 15 16. Electricity Generated by Hydro Power Stations in Niger State Compare to other Power Stations in Nigeria: 2004-2008 ……..……......... 16 17. Mineral Resources in Niger State by Type, Location & LGA …………. 17 ii 18. List of Water Resources in Niger State by Location and Size ………....... 18 19 Irrigation Projects in Niger State by LGA and Sited Area: 2003-2010.…. -

Determinants of Risk Status of Small Scale Farmers in Niger State, Nigeria

British Journal of Economics, Management & Trade 2(2): 92-108, 2012 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Determinants of Risk Status of Small Scale Farmers in Niger State, Nigeria J. N. Nmadu1*, G. P. Eze1 and A. J. Jirgi1 1Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension Technology, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Nigeria. Received 7th March 2012 th Research Article Accepted 4 April 2012 Online Ready 4th May 2012 ABSTRACT Aims: To ascertain the risk status of farming households and whether the risk status is accentuated by some factors. The specific objective is to determine the relationship between their risk status and socio-economic characteristics and food security status in the study area. Study Design: Cross-sectional study. Place and Duration of Study: Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension Technology, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Nigeria, between March 2011 and February, 2012. Methodology: The population for the study comprised farming households in Niger State. In order to obtain the sample for the study, two Local Government Areas (Suleja and Bosso) where randomly selected from where five farming communities were randomly selected and then ten farm families were randomly selected to give a total of 50 household from each Local Government Areas and 100 respondents for the study. The primary data covering background information, scale of production and yield, agricultural input use and access to credit, household food security and risk status were collected with structured questionnaire. Data analysis included the description of the socio-economic characteristics of the respondents using descriptive statistics and multinomial logistic regression used to confirm the determinants of risk status of the respondents. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

TENS Quick Facts

TENS TENS Transforming Education in Niger State Transforming Education in Niger State Transforming Education in Niger State (TENS) Programme Federal Republic of Nigeria Quick Facts TENS Programme September 2016 MRL Public Sector Consultants Ltd @tensprogramme Pepple House, 8 Broad Street Great Cambourne, Cambridge CB23 6HJ @tensprogramme England Tel: +44 (0)1954 715 715 www.mrl.uk.com www.tens-niger.com NIGER STATE MRL TENS -Quick Facts.qxp_A4 30/09/2016 15:00 Page 1 Quick Facts Introduction of classroom facilities, such as furniture, laboratories and equipment, the enhancement This quick facts sheet provides statistical of the school curriculum to meet the need of information following the analysis of data from students and society, and the availability of the Baseline Education Statistics (BES) and resources for teachers remuneration, to mention Infrastructure Surveys conducted in Niger State, a few. Nigeria as part of the overarching Transforming Education in Niger State (TENS) Programme. The Programme is currently being funded by the Niger State Government with additional funding The TENS Programme is a commitment by the being sought from international agencies and Niger State Government to transform state- non-governmental organisations (NGOs). owned primary and secondary schools with the aim of addressing many of the challenges in the educational sector. Examples of some of the Background to Niger State problems include the unavailability and shortage of teachers, overcrowded classrooms, poor and Established in 1976 and named after the River dilapidated school infrastructure, lack of and Niger, Niger State was created out of the defunct insufficient books, lack of facilities such as North-Western State. -

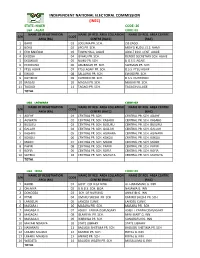

Niger Code: 26 Lga : Agaie Code: 01 Name of Registration Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: NIGER CODE: 26 LGA : AGAIE CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 BARO 01 LOGUMA PR. SCH. JSS ZAGO 2 BOKU 02 JIPO PR. SCH. MOH'D KUDU J.S.S. NAMI 3 EKO BADEGGI 03 TOWN HALL, AGAIE ADULT EDU. CENT. AGAIE 4 EKOSSA 04 ISYAKU PR. SCH. DENDO SECRETARY SCH. AGAIE 5 EKOWUGI 05 NUHU PR. SCH. D.G.S.S. AGAIE 6 EKOWUNA 06 ABUBAKAR PR. SCH. SWEMAN PR. SCH. 7 ETSU AGAIE 07 ETSU AGAIE PR. SCH. D.S.S. ETSU AGAIE 8 EWUGI 08 SALLAWU PR. SCH. EWUGI PR. SCH. 9 KUTIRIKO 09 KUTIRIKO PR. SCH. D.S.S. DUTRIRIKO 10 MAGAJI 10 MAGAJI PR. SCH. MAGAJI PR. SCH. 11 TAGAGI 11 TAGAGI PR. SCH. TAGAGI VILLAGE TOTAL LGA : AGWARA CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ADEHE 01 CENTRAL PR. SCH. CENTRAL PR. SCH. ADAHE 2 AGWATA 02 CENTRAL PR. SCH. KASABO CENTRAL PR. SCH. KASABO 3 BUSUEU 03 CENTRAL PR. SCH. BUSURU CENTRAL PR. SCH. BUSURU 4 GALLAH 04 CENTRAL PR. SCH. GALLAH CENTRAL PR. SCH. GALLAH 5 KASHINI 05 CENTRAL PR. SCH. AGWARA CENTRAL PR. SCH. AGWARA 6 KOKOLI 06 CENTRAL PR. SCH. KOKOLI CENTRAL PR. SCH. KOKOLI 7 MAGO 07 CENTRAL PR. SCH. MAGO CENTRAL PR. SCH. MAGO 8 PAPIRI 08 CENTRAL PR. SCH. PAPIRI CENTRAL PR. SCH. PAPIRI 9 ROFIA 09 CENTRAL PR. -

Technical Cooperation for Development Planning on the One

The Federal Republic of Nigeria Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency of Nigeria (SMEDAN) Technical Cooperation for Development Planning on the One Local Government One Product Programme for Revitalising the Rural Economy in the Federal Republic of Nigeria FINAL REPORT December 2011 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) IC Net Limited Overseas Merchandise Inspection Co., Ltd. Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. A2 Kano State Katsina State A9 Jigawa State Kunchi MakodaDambatta A9 Tsanyawa A9 Nigeria all area Bichi Minjibir Gabasawa Bagwai DawakinT Ungogo Shanono A2 Gezawa Tofa Dala RiminGad Ajingi Lake Chad Gwarzo Kumbotso Warawa Sokoto Lake Chad Kabo A2 Madobi DawakinKK a n o S t a t e Karaye Kura Gaya Kano NdjamenaNdjamena Wudil Maiduguri Garum Mallam Bunkure A2 Albasu Kiru Garko Kaduna Rogo Bebeji Kaduna Rano Kibiya Takai A2 AbujaAbuja A2 Sumaila Tundun Wada Ilorin A126 IbadanIbadan A2 LagosLagos A236 Enugu PortoPorto NovoNovo Benin City Doguwa A11 ¯ A11 Port Harcourt Yaounde A11 A11 Douala 0Malabo75 150 300 450 600 750 Kaduna State A11 Km A236 A235 0 10 20 40 60 80 100 A236 Km A126 A1 Zamfara State Kebbi State Kebbi State Rijau A1 A2 Agwara A1 Kaduna State A125 Mariga Kaduna State A125 Niger State A235 A125 Magama Kontogur A2 Borgu A125 A2 Rafi A125 Shiroro Niger State Niger State Mashegu Legend A1 Muya Wushishi p Airports Chanchaga A7 Bosso Primary road A2 Paikoro Local road Lavun A124 A2A124 Katcha Gurara Urban Areas Mokwa Gbako Tafa A124 Suleja A234 Intermittent stream A7 Bida A124 Perennial stream A7 Kwara State Edati Agaie Water bodies: Intermittent A1 Lavun A2 Water bodies: Perennial A1 A7 Lapai National Boundary O y o S t a t e A1 State Boundary A123 A1 Niger and Kano State Nassarawa State 0 10 20 40 60 80 A123100 Km A123 LGA Boundary K o g i S t a t e Source: ESRI Japan; Study Team Map of Nigeria iii Table of contents Abbreviations and acronyms ............................................................................................................... -

Nigeria Security Situation

Nigeria Security situation Country of Origin Information Report June 2021 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu) PDF ISBN978-92-9465-082-5 doi: 10.2847/433197 BZ-08-21-089-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office, 2021 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EASO copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Cover photo@ EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid - Left with nothing: Boko Haram's displaced @ EU/ECHO/Isabel Coello (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0), 16 June 2015 ‘Families staying in the back of this church in Yola are from Michika, Madagali and Gwosa, some of the areas worst hit by Boko Haram attacks in Adamawa and Borno states. Living conditions for them are extremely harsh. They have received the most basic emergency assistance, provided by our partner International Rescue Committee (IRC) with EU funds. “We got mattresses, blankets, kitchen pots, tarpaulins…” they said.’ Country of origin information report | Nigeria: Security situation Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge Stephanie Huber, Founder and Director of the Asylum Research Centre (ARC) as the co-drafter of this report. The following departments and organisations have reviewed the report together with EASO: The Netherlands, Ministry of Justice and Security, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Austria, Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum, Country of Origin Information Department (B/III), Africa Desk Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) It must be noted that the drafting and review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Nomadic Pastoralism and the Prevalence of Pulmonary Tuberculosis (Tb) in the North-Western Region of Nigeria by Abubakar Garba F

NOMADIC PASTORALISM AND THE PREVALENCE OF PULMONARY TUBERCULOSIS (TB) IN THE NORTH-WESTERN REGION OF NIGERIA BY ABUBAKAR GARBA FADA B. Sc Geography (Sokoto), M. Sc Geography (Ibadan) A Thesis in the Department of Geography Submitted to the Faculty of The Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF IBADN 2014 ABSTRACT The pattern of human mobility affects the spread of infectious diseases, particularly tuberculosis (TB), the transmission which is associated with several factors, including the consumption of unpasteurised milk. However, the very few studies that have been conducted on the role of seasonal migration on disease transmission are inconclusive. In particular, the transmission of TB along seasonal migration routes in Nigeria has not been given adequate attention. This study, therefore, examined the prevalence of pulmonary TB in the North-western region of Nigeria. Using a survey design, disease ecology and distance decay effect provided the framework. Purposive and random sampling techniques were used to collect data from the records of 15 Directly Observed Therapy Short-course (DOTS) each along and off-route centres. A structured questionnaire was administered to 461 (26.6%) proportionately and randomly selected patients receiving treatment. Data were collected on the socio-demographic (gender, age, marital status, population size, work history, occupation type, income and literacy levels), behavioural (visits to health centre to treat TB, smoking, consumption of unpasteurised milk profiles and perceived causes of TB), and environmental (history of infection with TB, access to healthcare and exposure to dust) factors. Data were also collected on distance (determined from topographical maps) along and off-route TB centres, duration of stay in a place and number of health facilities.