Drilling Down: an Analysis of Drill Music in Relation to Race and Policing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE 1.0 PERSONAL DATA: NAME: Edwin Richard Galea BSc, Dip.Ed, Phd, CMath, FIMA, CEng, FIFireE HOME ADDRESS: TELEPHONE: 6 Papillons Walk (home) +44 (0) 20 8318 7432 Blackheath SE3 9SF (work) +44 (0) 20 8331 8730 United Kingdom (mobile) +44 (0)7958 807 303 EMAIL: WEB ADDRESS: Work: [email protected] http://staffweb.cms.gre.ac.uk/~ge03/ Private: [email protected] PLACE AND DATE OF BIRTH: NATIONALITY: Melbourne Australia, 07/12/57 Dual Citizenship Australia and UK MARITAL STATUS: Married, no children EDUCATION: 1981-84: The University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia. PhD in Astrophysics: The Mathematical Modelling of Rotating Magnetic Upper Main Sequence Stars 1976-80: Monash University, Melbourne, Australia Dip.Ed. and B.Sc.(Hons) in Science, with a double major in mathematics and physics HII(A) 1970-75: St Albans High School, Melbourne, Australia 2.1 CURRENT POSTS: CAA Professor of Mathematical Modelling, University of Greenwich, (1992 - ) Founding Director, Fire Safety Engineering Group, University of Greenwich, (1992 - ) Vice-Chair International Association of Fire Safety Science (Feb 2014 - ) Visiting Professor, University of Ghent, Belgium (2008 - ) Visiting Professor, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences (HVL), Haugesund, Norway, (Nov 2015 - ) Technical Advisor Clevertronics (Australia) (March 2015 - ) Associate Editor, The Aeronautical Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society (Nov 2013 - ) Associate Editor, Safety Science (Feb 2017 - ) Expert to the Grenfell Inquiry (Sept 2017 - ) 2.2 PREVIOUS POSTS: External Examiner, Trinity College Dublin (June 2013 – Feb 2017) Visiting Professor, Institut Supérieur des Matériaux et Mécaniques Avancés (ISMANS), Le Mans, France (2010 - 2016) Associate Editor of Fire Science Reviews until it merged with another fire journal (2013 – DOC REF: GALEA_CV/ERG/1/0618/REV 1.0 1 2017) Associate Editor of the Journal of Fire Protection Engineering until it merged with another fire journal (2008 – 2013) 3.0 QUALIFICATIONS: DEGREES /DIPLOMAS Ph.D. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

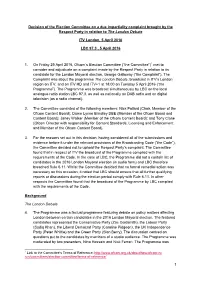

1 Decision of the Election Committee on a Due Impartiality Complaint Brought by the Respect Party in Relation to the London Deba

Decision of the Election Committee on a due impartiality complaint brought by the Respect Party in relation to The London Debate ITV London, 5 April 2016 LBC 97.3 , 5 April 2016 1. On Friday 29 April 2016, Ofcom’s Election Committee (“the Committee”)1 met to consider and adjudicate on a complaint made by the Respect Party in relation to its candidate for the London Mayoral election, George Galloway (“the Complaint”). The Complaint was about the programme The London Debate, broadcast in ITV’s London region on ITV, and on ITV HD and ITV+1 at 18:00 on Tuesday 5 April 2016 (“the Programme”). The Programme was broadcast simultaneously by LBC on the local analogue radio station LBC 97.3, as well as nationally on DAB radio and on digital television (as a radio channel). 2. The Committee consisted of the following members: Nick Pollard (Chair, Member of the Ofcom Content Board); Dame Lynne Brindley DBE (Member of the Ofcom Board and Content Board); Janey Walker (Member of the Ofcom Content Board); and Tony Close (Ofcom Director with responsibility for Content Standards, Licensing and Enforcement and Member of the Ofcom Content Board). 3. For the reasons set out in this decision, having considered all of the submissions and evidence before it under the relevant provisions of the Broadcasting Code (“the Code”), the Committee decided not to uphold the Respect Party’s complaint. The Committee found that in respect of ITV the broadcast of the Programme complied with the requirements of the Code. In the case of LBC, the Programme did not a contain list of candidates in the 2016 London Mayoral election (in audio form) and LBC therefore breached Rule 6.11. -

Only Believe Song Book from the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, Write To

SONGS OF WORSHIP Sung by William Marrion Branham Only Believe SONGS SUNG BY WILLIAM MARRION BRANHAM Songs of Worship Most of the songs contained in this book were sung by Brother Branham as he taught us to worship the Lord Jesus in Spirit and Truth. This book is distributed free of charge by the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, with the prayer that it will help us to worship and praise the Lord Jesus Christ. To order the Only Believe song book from the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, write to: Spoken Word Publications P.O. Box 888 Jeffersonville, Indiana, U..S.A. 47130 Special Notice This electronic duplication of the Song Book has been put together by the Grand Rapids Tabernacle for the benefit of brothers and sisters around the world who want to replace a worn song book or simply desire to have extra copies. FOREWARD The first place, if you want Scripture, the people are supposed to come to the house of God for one purpose, that is, to worship, to sing songs, and to worship God. That’s the way God expects it. QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS, January 3, 1954, paragraph 111. There’s something about those old-fashioned songs, the old-time hymns. I’d rather have them than all these new worldly songs put in, that is in Christian churches. HEBREWS, CHAPTER SIX, September 8, 1957, paragraph 449. I tell you, I really like singing. DOOR TO THE HEART, November 25, 1959. Oh, my! Don’t you feel good? Think, friends, this is Pentecost, worship. This is Pentecost. Let’s clap our hands and sing it. -

In the United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida Fort Myers Division

Case 2:19-cv-00843-JES-NPM Document 1 Filed 11/25/19 Page 1 of 46 PageID 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA FORT MYERS DIVISION : PRO MUSIC RIGHTS, LLC and SOSA : ENTERTAINMENT LLC, : : Civil Action No. 2:19-cv-00843 Plaintiffs, : : v. : : SPOTIFY AB, a Swedish Corporation; SPOTIFY : USA, INC., a Delaware Corporation; SPOTIFY : LIMITED, a United Kingdom Corporation; and : SPOTIFY TECHNOLOGY S.A., a Luxembourg : Corporation, : : Defendants. PLAINTIFFS’ COMPLAINT WITH INJUNCTIVE RELIEF SOUGHT AND DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Plaintiffs Pro Music Rights, LLC (“PMR”), which is a public performance rights organization representing over 2,000,000 works of artists, publishers, composers and songwriters, and Sosa Entertainment LLC (“Sosa”), which has not been paid for 550,000,000+ streams of music on the Spotify platform, file this Complaint seeking millions of dollars of damages against Defendants Spotify AB, Spotify USA, Inc., Spotify Limited, and Spotify Technology S.A. (collectively, “Spotify” or “Defendants”), alleging as follows: NATURE OF ACTION 1. Plaintiffs bring this action to redress substantial injuries Spotify caused by failing to fulfill its duties and obligations as a music streaming service, willfully removing content for anti-competitive reasons, engaging in unfair and deceptive business practices, Case 2:19-cv-00843-JES-NPM Document 1 Filed 11/25/19 Page 2 of 46 PageID 2 obliterating Plaintiffs’ third-party contracts and expectations, refusing to pay owed royalties and publicly performing songs without license. 2. In addition to live performances and social media engagement, Plaintiffs rely heavily on the streaming services of digital music service providers, such as and including Spotify, to organically build and maintain their businesses. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 52 28.12.2019

28.12.2019 England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 52 Pos Vorwochen Woc BP Titel und Interpret 2019 / 52 - 1 1 --- --- 1N1 1 I Love Sausage Rolls . LadBaby 22342 Own It . Stormzy feat. Ed Sheeran & Burna Boy 34252 Before You Go . Lewis Capaldi 43472 Don't Start Now . Dua Lipa 5713922 Last Christmas . Wham! 6 --- --- 1N6 Audacity . Stormzy feat. Headie One 75575 Roxanne . Arizona Zervas 8681052 All I Want For Christmas Is You . Mariah Carey 9 --- --- 1N9 Lessons . Stormzy 10 1 1 201 11 Dance Monkey . Tones And I . 11 8 14 48 River . Ellie Goulding 12 11 --- 211 Adore You . Harry Styles 13 9 6 53 Everything I Wanted . Billie Eilish 14 14 22 1082 Fairytale Of New York . The Pogues & Kirsty McColl 15 12 11 296 Bruises . Lewis Capaldi 16 16 26 751 2 Merry Christmas Everyone . Shakin' Stevens 17 15 23 781 5 Do They Know It's Christmas ? . Band Aid 18 47 55 518 Watermelon Sugar . Harry Styles 19 24 39 3910 Step Into Christmas . Elton John 20 17 12 312 Blinding Lights . The Weeknd . 21 19 18 1314 Hot Girl Bummer . Blackbear 22 21 15 93 Lose You To Love Me . Selena Gomez 23 23 20 1020 Pump It Up . Endor 24 25 32 347 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas . Michael Bublé 25 29 43 283 One More Sleep . Leona Lewis 26 35 40 426 Falling . Trevor Daniel 27 51 --- 3210 Lucid Dreams . Juice WRLD 28 31 33 2813 Santa Tell Me . Ariana Grande 29 34 44 804 I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday . -

Trap Spaces, Trap Music: Harriet Jacobs, Fetty Wap, and Emancipation As Entrapment

Trap Spaces, Trap Music: Harriet Jacobs, Fetty Wap, and Emancipation as Entrapment SEAN M. KENNEDY Set in a New York City trap house—an apartment that serves as the hub for an outlaw drug business—Fetty Wap’s 2014 song and video “Trap Queen” depicts the stacks of U.S. currency and the manufacture of product that are core aspects of the genre of trap music. But the song and video also portray an outlier to this strategic essentialism: namely, the loving romance at its center which challenges the mainstream common sense of the misogyny of rap. Likewise, the sonics of “Trap Queen”—upbeat, even joyful—contrast with the aural hardness of much of the genre. In these ways, “Trap Queen” is an important pop-cultural political intervention against both the enduring pathologizing of Black life and the sense of siege with which many Black people, especially poor ones, are perceived to live.1 But while Fetty Wap’s persona in “Trap Queen” can be understood as a homo- economicus figure (Wynter 123) of the informal economy—a breadwinner who can self-determine his own life, albeit within the narrow bounds of criminalized enterprise—that burdened self-possession is doubled for his female partner presented as a woman who will happily do anything for her “man,” from cooking crack to giving him a lap dance (see Figure 1). These labors are shown to be uncoerced. Nevertheless, the larger structures of the racial-capitalist formal economy essentially force many Black women into such gendered survival labor. Indeed, the situation of these women, which Fetty Wap’s “trap queen” only partially evokes, illustrates the thinness of freedom under liberal democracy of which emancipation from slavery is considered paradigmatic. -

Drill Rap and Violent Crime in London

Violent music vs violence and music: Drill rap and violent crime in London Bennett Kleinberg1,2 and Paul McFarlane1,3 1 Department of Security and Crime Science, University College London 2 Dawes Centre for Future Crime, University College London 3 Jill Dando Institute for Global City Policing, University College London1 Abstract The current policy of removing drill music videos from social media platforms such as YouTube remains controversial because it risks conflating the co-occurrence of drill rap and violence with a causal chain of the two. Empirically, we revisit the question of whether there is evidence to support the conjecture that drill music and gang violence are linked. We provide new empirical insights suggesting that: i) drill music lyrics have not become more negative over time if anything they have become more positive; ii) individual drill artists have similar sentiment trajectories to other artists in the drill genre, and iii) there is no meaningful relationship between drill music and ‘real- life’ violence when compared to three kinds of police-recorded violent crime data in London. We suggest ideas for new work that can help build a much-needed evidence base around the problem. Keywords: drill music, gang violence, sentiment analysis INTRODUCTION The role of drill music – a subgenre of aggressive rap music (Mardean, 2018) – in inciting gang- related violence remains controversial. The current policy towards the drill-gang violence nexus is still somewhat distant from understanding the complexity of drill music language and how drill music videos are consumed by a wide range of social media users. To build the evidence base for more appropriate policy interventions by the police and social media companies, our previous work looked at dynamic sentiment trajectories (i.e. -

Drill Music in the Dock

1 Drill music in the dock A look at the use of drill music in criminal trials and a practical guide for defence practitioners Introduction The recent Sewell report has, some might say deliberately and for political reasons, sparked further exchanges between the perceived opposing sides in the so-called ‘culture wars’. This has sought to paint an overall picture of the treatment of minorities in Britain which is it at odds with the lived experience of many. To give a judicial summing-up style warning up front: ‘if we appear to express a view, reject it unless it accords with your own’. The authors of this article are, at best, only really placed to speak of the situation as it affects the Criminal Justice System. How the dynamics and politics of race play out in our courtrooms up and down the country. In these places, inequalities are laid bare on a daily basis in terms of the proportional representation of the different ethnic groups. The recent Sewell report at least acknowledges this imbalance: “..people from ethnic minorities are overrepresented at many points of the criminal justice system. The largest disparities appear at the point of stop and search and, as the Lammy Review pointed out, at arrest, custodial sentencing and prison population. Among ethnic minority groups, Black people are usually the most overrepresented.1” 1 h#ps://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/a#achment_data/file/ 974507/20210331_-_CRED_Report_-_FINAL_-_Web_Accessible.pdf 2 The David Lammy Review2 came to a number of conclusions about the way people, particularly young black men, are treated within the Criminal Justice System.