Exploring the C-SPAN Archives: Advancing the Research Agenda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

2012 Election Preview: the Projected Impact on Congressional Committees

2012 Election Preview: the Projected Impact on Congressional Committees K&L Gates LLP 1601 K Street Washington, DC 20006 +1.202.778.9000 October 2012 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1-2 Introduction 3 House Key Code 4 House Committee on Administration 5 House Committee on Agriculture 6 House Committee on Appropriations 7 House Committee on Armed Services 8 House Committee on the Budget 9 House Committee on Education and the Workforce 10 House Committee on Energy and Commerce 11 House Committee on Ethics 12 House Committee on Financial Services 13 House Committee on Foreign Affairs 14 House Committee on Homeland Security 15 House Committee on the Judiciary 16 House Committee on Natural Resources 17 House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform 18 House Committee on Rules 19 House Committee on Science, Space and Technology 20 House Committee on Small Business 21 House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure 22 House Committee on Veterans' Affairs 23 House Committee on Ways and Means 24 House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence 25 © 2012 K&L Gates LLP Page 1 Senate Key Code 26 Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry 27 Senate Committee on Appropriations 28 Senate Committee on Armed Services 29 Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs 30 Senate Committee on the Budget 31 Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation 32 Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources 33 Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works 34 Senate Committee on Finance 35 Senate Committee on Foreign -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

After the Financial Crisis: Ongoing Challenges Facing Delphi Retirees

AFTER THE FINANCIAL CRISIS: ONGOING CHALLENGES FACING DELPHI RETIREES FIELD HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 13, 2010 Printed for the use of the Committee on Financial Services Serial No. 111–143 ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 61–847 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 18:29 Nov 12, 2010 Jkt 061847 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 K:\DOCS\61847.TXT TERRIE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts, Chairman PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama MAXINE WATERS, California MICHAEL N. CASTLE, Delaware CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York PETER T. KING, New York LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois EDWARD R. ROYCE, California NYDIA M. VELA´ ZQUEZ, New York FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina RON PAUL, Texas GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois BRAD SHERMAN, California WALTER B. JONES, JR., North Carolina GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York JUDY BIGGERT, Illinois DENNIS MOORE, Kansas GARY G. MILLER, California MICHAEL E. CAPUANO, Massachusetts SHELLEY MOORE CAPITO, West Virginia RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas JEB HENSARLING, Texas WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri SCOTT GARRETT, New Jersey CAROLYN MCCARTHY, New York J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina JOE BACA, California JIM GERLACH, Pennsylvania STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts RANDY NEUGEBAUER, Texas BRAD MILLER, North Carolina TOM PRICE, Georgia DAVID SCOTT, Georgia PATRICK T. -

Anti-‐Science Climate Denier Caucus Georgia

ANTI-SCIENCE CLIMATE DENIER CAUCUS Climate change is happening, and humans are the cause. But a shocking number of congressional Republicans—more than 55 percent—refuse to accept it. One hundred and fifty-seven elected representatives from the 113th Congress have taken more than $51 million from the fossil-fuel industry, which is the driving force behind the carbon emissions that cause climate change. These representatives deny what more than 97 percent of climate scientists say is happening: Current human activity creates the greenhouse gas emissions that trap heat within the atmosphere and cause climate change. And their constituents are paying the price, with Americans across the nation suffering 368 climate-related national disaster declarations since 2011. There were 25 extreme weather events that each caused at least $1 billion in damage since 2011, including Superstorm Sandy and overwhelming drought that has covered almost the entire western half of the United States. Combined, these extreme weather events were responsible for 1,107 fatalities and up to $188 billion in economic damages. GEORGIA Despite the overwhelming scientific consensus and high costs to taxpayers, Georgia has seven resident deniers who have taken $783,233 in dirty energy contributions. The state has suffered five climate-related disaster declarations since 2011. Georgia suffered from “weather whiplash” this past May: excessive flooding where “exceptional drought,” the worst category of drought, had existed just a few months earlier. Below are quotes from five of Georgia’s resident deniers who refuse to believe there is a problem to address: Rep. Paul Broun (R-GA-10): “Scientists all over this world say that the idea of human induced global climate change is one of the greatest hoaxes perpetrated out of the scientific community. -

The Rise of Viral Marketing Through the New Media of Social Media Rebecca J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Faculty Publications and Presentations School of Business 2009 The Rise of Viral Marketing through the New Media of Social Media Rebecca J. Larson Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/busi_fac_pubs Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Larson, Rebecca J., "The Rise of Viral Marketing through the New Media of Social Media" (2009). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 6. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/busi_fac_pubs/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Business at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lingley, R 1 MKT7001-11 1 RUNNING HEAD: Lingley, R 1 MKT7001-11 The Rise of Viral Marketing through the New Media of Social Media: An Analysis and Implications for Consumer Behavior Rebecca J. Lingley Larson NorthCentral University Lingley, R 1 MKT7001-11 2 Table of Contents Title Page …………………………………………………..…………………………. 1 Table of Contents …………….………………………….………………………….. 2 Executive Summary ……….………………………….…………………………….. 3 Introduction …………………..………………………………………………………. 5 Changing consumer behavior: Analyzing innovation’s impact -

CQ Committee Guide

SPECIAL REPORT Committee Guide Complete House and senate RosteRs: 113tH CongRess, seCond session DOUGLAS GRAHAM/CQ ROLL CALL THE PEOPLE'S BUSINESS: The House Energy and Commerce Committee, in its Rayburn House Office Building home, marks up bills on Medicare and the Federal Communications Commission in July 2013. www.cq.com | MARCH 24, 2014 | CQ WEEKLY 431 09comms-cover layout.indd 431 3/21/2014 5:12:22 PM SPECIAL REPORT Senate Leadership: 113th Congress, Second Session President of the Senate: Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. President Pro Tempore: Patrick J. Leahy, D-Vt. DEMOCRATIC LEADERS Majority Leader . Harry Reid, Nev. Steering and Outreach Majority Whip . Richard J. Durbin, Ill. Committee Chairman . Mark Begich, Alaska Conference Vice Chairman . Charles E. Schumer, N.Y. Chief Deputy Whip . Barbara Boxer, Calif. Policy Committee Chairman . Charles E. Schumer, N.Y. Democratic Senatorial Campaign Conference Secretary . Patty Murray, Wash. Committee Chairman . Michael Bennet, Colo. REPUBLICAN LEADERS Minority Leader . Mitch McConnell, Ky. Policy Committee Chairman . John Barrasso, Wyo. Minority Whip . John Cornyn, Texas Chief Deputy Whip . Michael D. Crapo, Idaho Conference Chairman . John Thune, S.D. National Republican Senatorial Conference Vice Chairman . Roy Blunt, Mo. Committee Chairman . Jerry Moran, Kan. House Leadership: 113th Congress, Second Session Speaker of the House: John A. Boehner, R-Ohio REPUBLICAN LEADERS Majority Leader . Eric Cantor, Va. Policy Committee Chairman . James Lankford, Okla. Majority Whip . Kevin McCarthy, Calif. Chief Deputy Whip . Peter Roskam, Ill. Conference Chairwoman . .Cathy McMorris Rodgers, Wash. National Republican Congressional Conference Vice Chairwoman . Lynn Jenkins, Kan. Committee Chairman . .Greg Walden, Ore. Conference Secretary . Virginia Foxx, N.C. -

Improvement Session, 8/6-7/76 - Press Advance (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 24, folder “Press Office - Improvement Session, 8/6-7/76 - Press Advance (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 24 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library AGENDA FOR MEETING WITH PRESS SECRETARY Friday, August 6, 1976 4:00 p.m. Convene Meeting - Roosevelt Room (Ron) 4:05p.m. Overview from Press Advance Office (Doug) 4:15 p.m. Up-to-the-Minute Report from Kansas City {Dave Frederickson) 4:20 p.m. The Convention (Ron} 4:30p.m. The Campaign (Ron) 4:50p.m. BREAK 5:00p.m. Reconvene Meeting - Situation Room (Ron) 5:05 p. in. Presentation of 11 Think Reports 11 11 Control of Image-Making Machinery11 (Dorrance Smith) 5:15p.m. "Still Photo Analysis - Ford vs. Carter 11 (David Wendell) 5:25p.m. Open discussion Reference July 21 memo, Blaser to Carlson "What's the Score 11 6:30p.m. -

June 19, 2020 Volume 4, No

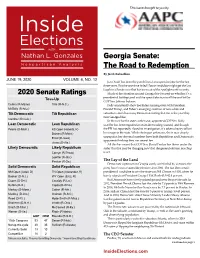

This issue brought to you by Georgia Senate: The Road to Redemption By Jacob Rubashkin JUNE 19, 2020 VOLUME 4, NO. 12 Jon Ossoff has been the punchline of an expensive joke for the last three years. But the one-time failed House candidate might get the last laugh in a Senate race that has been out of the spotlight until recently. 2020 Senate Ratings Much of the attention around Georgia has focused on whether it’s a Toss-Up presidential battleground and the special election to fill the seat left by GOP Sen. Johnny Isakson. Collins (R-Maine) Tillis (R-N.C.) Polls consistently show Joe Biden running even with President McSally (R-Ariz.) Donald Trump, and Biden’s emerging coalition of non-white and Tilt Democratic Tilt Republican suburban voters has many Democrats feeling that this is the year they turn Georgia blue. Gardner (R-Colo.) In the race for the state’s other seat, appointed-GOP Sen. Kelly Lean Democratic Lean Republican Loeffler has been engulfed in an insider trading scandal, and though Peters (D-Mich.) KS Open (Roberts, R) the FBI has reportedly closed its investigation, it’s taken a heavy toll on Daines (R-Mont.) her image in the state. While she began unknown, she is now deeply Ernst (R-Iowa) unpopular; her abysmal numbers have both Republican and Democratic opponents thinking they can unseat her. Jones (D-Ala.) All this has meant that GOP Sen. David Perdue has flown under the Likely Democratic Likely Republican radar. But that may be changing now that the general election matchup Cornyn (R-Texas) is set. -

Employees of Northrop Grumman Political Action Committee (ENGPAC) 2017 Contributions

Employees of Northrop Grumman Political Action Committee (ENGPAC) 2017 Contributions Name Candidate Office Total ALABAMA $69,000 American Security PAC Rep. Michael Dennis Rogers (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Byrne for Congress Rep. Bradley Roberts Byrne (R) Congressional District 01 $5,000 BYRNE PAC Rep. Bradley Roberts Byrne (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Defend America PAC Sen. Richard Craig Shelby (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Martha Roby for Congress Rep. Martha Roby (R) Congressional District 02 $10,000 Mike Rogers for Congress Rep. Michael Dennis Rogers (R) Congressional District 03 $6,500 MoBrooksForCongress.Com Rep. Morris Jackson Brooks, Jr. (R) Congressional District 05 $5,000 Reaching for a Brighter America PAC Rep. Robert Brown Aderholt (R) Leadership PAC $2,500 Robert Aderholt for Congress Rep. Robert Brown Aderholt (R) Congressional District 04 $7,500 Strange for Senate Sen. Luther Strange (R) United States Senate $15,000 Terri Sewell for Congress Rep. Terri Andrea Sewell (D) Congressional District 07 $2,500 ALASKA $14,000 Sullivan For US Senate Sen. Daniel Scott Sullivan (R) United States Senate $5,000 Denali Leadership PAC Sen. Lisa Ann Murkowski (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 True North PAC Sen. Daniel Scott Sullivan (R) Leadership PAC $4,000 ARIZONA $29,000 Committee To Re-Elect Trent Franks To Congress Rep. Trent Franks (R) Congressional District 08 $4,500 Country First Political Action Committee Inc. Sen. John Sidney McCain, III (R) Leadership PAC $3,500 (COUNTRY FIRST PAC) Gallego for Arizona Rep. Ruben M. Gallego (D) Congressional District 07 $5,000 McSally for Congress Rep. Martha Elizabeth McSally (R) Congressional District 02 $10,000 Sinema for Arizona Rep. -

USSYP 2010 Yearbook.Pdf

THE HEARST FOUNDATIONS DIRECTORS William Randolph Hearst III UNTED STATE PESIDENTR James M. Asher Anissa B. Balson David J. Barrett S Frank A. Bennack, Jr. SE NAT E YO John G. Conomikes Ronald J. Doerfler George R. Hearst, Jr. John R. Hearst, Jr. U Harvey L. Lipton T Gilbert C. Maurer H PROGR A M Mark F. Miller Virginia H. Randt Paul “Dino” Dinovitz EXCUTIE V E DIRECTOR F ORT Rayne B. Guilford POAR GR M DI RECTOR Y - U N ITED S TATES SE NATE YOUTH PROGR A M E IGHT H A N N U A L WA S H INGTON WEEK 2010 sponsored BY THE UNITED STATES SENATE UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGRAM FUNDED AND ADMINISTERED BY THE THE HEARST FOUNDATIONS FORTY-EIGHTH ANNUAL WASHINGTON WEEK H M ARCH 6 – 1 3 , 2 0 1 0 90 NEW MONTGOMERY STREET · SUITE 1212 · SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105-4504 WWW.USSENATEYOUTH.ORG Photography by Jakub Mosur Secondary Photography by Erin Lubin Design by Catalone Design Co. “ERE TH IS A DEBT OF SERV ICE DUE FROM EV ERY M A N TO HIS COUNTRY, PROPORTIONED TO THE BOUNTIES W HICH NATUR E A ND FORTUNE H AV E ME ASURED TO HIM.” —TA H O M S J E F F E R S ON 2010 UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGR A M SENATE A DVISORY COMMITTEE HONOR ARY CO-CH AIRS SENATOR V ICE PRESIDENT SENATOR HARRY REID JOSEPH R. BIDEN MITCH McCONNELL Majority Leader President of the Senate Republican Leader CO-CH AIRS SENATOR SENATOR ROBERT P. -

Illinois Congressional Delegation Bios

Illinois Congressional Delegation Bios Senator Richard Durbin (D-IL) Senator Dick Durbin, a Democrat from Springfield, is the 47th U.S. Senator from the State of Illinois, the state’s senior senator, and the convener of Illinois’ bipartisan congressional delegation. Durbin also serves as the Assistant Democratic Leader, the second highest ranking position among the Senate Democrats. Also known as the Minority Whip, Senator Durbin has been elected to this leadership post by his Democratic colleagues every two years since 2005. Elected to the U.S. Senate on November 5, 1996, and re-elected in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Durbin fills the seat left vacant by the retirement of his long-time friend and mentor, U.S. Senator Paul Simon. Durbin sits on the Senate Judiciary, Appropriations, and Rules Committees. He is the Ranking Member of the Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on the Constitution and the Appropriations Committee's Defense Subcommittee. Senator Tammy Duckworth (D-IL) U.S. Senator Tammy Duckworth is an Iraq War Veteran, Purple Heart recipient and former Assistant Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs. She was among the first Army women to fly combat missions during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Duckworth served in the Reserve Forces for 23 years before retiring from military service in 2014 at the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. She was elected to the U.S. Senate in 2016 after representing Illinois’s Eighth Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives for two terms. In 2004, Duckworth was deployed to Iraq as a Black Hawk helicopter pilot for the Illinois Army National Guard.