Roman Popadiuk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read a Transcript of Our Interview with Rick Klein

It’s All Journalism www.itsalljournalism.com 1 Rick Klein, Political Director, ABC News Megan Cloherty, Producer, It’s All Journalism Welcome to It's all Journalism. I'm Megan Cloherty joined by co-producers Anna Miars, Julie O'Donoghue and Michael O'Connell. And today we have Rick Klein with us. Rick is political director at ABC News. He is currently senior Washington editor for World News Tonight with Diane Sawyer. He also co-hosts Top Line, a political webcast, that is daily isn't it? Rick Klein, Political Director, ABC News It's weekly now. But we'll go back to that. Megan Cloherty We'll go back to that. It's weekly! He's a regular guest on Fox News and NPR. A graduate of Princeton, Rick spent his early career at the Dallas Morning News and the Boston Globe. Thanks for being here. Rick Klein My pleasure. Michael O'Connell, Producer, It’s All Journalism And you just came from ABC, you were doing a show. Rick Klein Yeah, we just did This Week roundtable, actually my maiden appearance on that roundtable, so that was fun. Megan Cloherty What was the topic of conversation? Rick Klein A little bit about the Obama health care law and the ramifications of that delay. Big story this week. Immigration, which of course, is consuming Washington for much of the summer. And then just wrapping President Obama's trip to Africa and the unique joint appearance with President Bush over in Tanzania. Megan Cloherty So lets start with -- and we're going to back track big time here -- how your career got started. -

Improvement Session, 8/6-7/76 - Press Advance (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 24, folder “Press Office - Improvement Session, 8/6-7/76 - Press Advance (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 24 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library AGENDA FOR MEETING WITH PRESS SECRETARY Friday, August 6, 1976 4:00 p.m. Convene Meeting - Roosevelt Room (Ron) 4:05p.m. Overview from Press Advance Office (Doug) 4:15 p.m. Up-to-the-Minute Report from Kansas City {Dave Frederickson) 4:20 p.m. The Convention (Ron} 4:30p.m. The Campaign (Ron) 4:50p.m. BREAK 5:00p.m. Reconvene Meeting - Situation Room (Ron) 5:05 p. in. Presentation of 11 Think Reports 11 11 Control of Image-Making Machinery11 (Dorrance Smith) 5:15p.m. "Still Photo Analysis - Ford vs. Carter 11 (David Wendell) 5:25p.m. Open discussion Reference July 21 memo, Blaser to Carlson "What's the Score 11 6:30p.m. -

Introduction Ronald Reagan’S Defining Vision for the 1980S— - and America

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Ronald Reagan’s Defining Vision for the 1980s— -_and America There are no easy answers, but there are simple answers. We must have the courage to do what we know is morally right. ronald reagan, “the speech,” 1964 Your first point, however, about making them love you, not just believe you, believe me—I agree with that. ronald reagan, october 16, 1979 One day in 1924, a thirteen-year-old boy joined his parents and older brother for a leisurely Sunday drive roaming the lush Illinois country- side. Trying on eyeglasses his mother had misplaced in the backseat, he discovered that he had lived life thus far in a “haze” filled with “colored blobs that became distinct” when he approached them. Recalling the “miracle” of corrected vision, he would write: “I suddenly saw a glori- ous, sharply outlined world jump into focus and shouted with delight.” Six decades later, as president of the United States of America, that extremely nearsighted boy had become a contact lens–wearing, fa- mously farsighted leader. On June 12, 1987, standing 4,476 miles away from his boyhood hometown of Dixon, Illinois, speaking to the world from the Berlin Wall’s Brandenburg Gate, Ronald Wilson Reagan em- braced the “one great and inescapable conclusion” that seemed to emerge after forty years of Communist domination of Eastern Eu- rope. “Freedom leads to prosperity,” Reagan declared in his signature For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. -

Video Tapes Boxes 116 - 134

Box Item Location Sub-series Description Video Tapes Series 13: Video Tapes Boxes 116 - 134 116 1 01-8-26- Senate Democratic Leadership Council Conference, Cleveland 08-06-0-1 - April 1981 - VHS. 2 KNBC-TV, Los Angeles - interview of John Glenn during his 1984 presidential campaign - November 27, 1983 - VHS. 3 John Glenn speech given at The Ohio State University during his 1984 presidential campaign - November 30, 1983 - VHS. 4 John Glenn speech on nuclear arms control at The Ohio State University during his 1984 presidential campaign - December 1983 - VHS. 5 "Believe in the Future Again" - 1984 presidential campaign video - circa 1983-1984 - VHS. 6 "Believe in the Future Again" - 1984 presidential campaign - circa 1983-1984 - VHS (copy 2). 7 "International Dateline" - panel discussions on U.S./Israeli relations with Senators John Glenn, Robert Dole, and Christopher Dodd, sponsored by the United Jewish Appeal - May 12 & 19, 1985 - VHS. 8 Statements by Senators Howard Metzenbaum and John Glenn taped for a Cable in the Classroom Workshop, sponsored by Cox Cable Systems - circa 1985 - VHS. 9 John Glenn’s taped statement to the National Technological University graduation ceremony - Cambridge, Ohio - November 19, 1986 – VHS 10 Give Kids the World Foundation promotional video narrated by Walter Cronkite, produced by Disney- MGM Studios - circa 1986 - VHS. 11 Public service announcement, International Aerospace Hall of Fame - June 12, 1987 -VHS. 12 Floor statement on the Persian Gulf - June 17, 1987; Democratic debate on "Firing Line" - July 1, 1987; and Trade Bill hearing - July 14, 1987 - VHS. 13 John Glenn’s floor statement on the Republican Campaign Committee’s strategy of portraying Howard Metzenbaum as a communist sympathizer - July 29, 1987 - VHS. -

Statement of Brian Karem

STATEMENT OF BRIAN KAREM I write to provide you with background about myself and to tell you my side of the story regarding what happened at the Social Media Summit on July 11, 2019. I have been a political reporter for almost 40 years. I have also covered crime and wars, and I have run community newspapers. I’ve been jailed, shot at, beaten, and threatened. I am currently Playboy’s senior White House correspondent and a political analyst for CNN. I am president of the Maryland, Delaware, and District of Columbia Press Association. In 1990, I was jailed for contempt of court after refusing to disclose the name of confidential sources who helped me arrange a telephone interview with a jailed murder suspect, after which I was awarded the National Press Club’s Freedom of the Press award. I went on to work as executive editor of The Sentinel Newspapers in Maryland and as producer and television correspondent for America’s Most Wanted. I have also authored seven books. I have covered six White Houses. While I have held my current hard pass since last year, in the past I also held hard passes. My experience in the White House is important because I can tell you, point blank, that the behavior of the press corps today is tame by comparison. The first time I walked into the White House I was 25. It was 1986 and Ronald Reagan was president. The first person I met was Helen Thomas, who covered the White House under ten Presidents, and who, as it turns out, knew my great grandfather from Lebanon. -

Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time

The Business of Getting “The Get”: Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung The Joan Shorenstein Center I PRESS POLITICS Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 IIPUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government The Business of Getting “The Get” Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 INTRODUCTION In “The Business of Getting ‘The Get’,” TV to recover a sense of lost balance and integrity news veteran Connie Chung has given us a dra- that appears to trouble as many news profes- matic—and powerfully informative—insider’s sionals as it does, and, to judge by polls, the account of a driving, indeed sometimes defining, American news audience. force in modern television news: the celebrity One may agree or disagree with all or part interview. of her conclusion; what is not disputable is that The celebrity may be well established or Chung has provided us in this paper with a an overnight sensation; the distinction barely nuanced and provocatively insightful view into matters in the relentless hunger of a Nielsen- the world of journalism at the end of the 20th driven industry that many charge has too often century, and one of the main pressures which in recent years crossed over the line between drive it as a commercial medium, whether print “news” and “entertainment.” or broadcast. One may lament the world it Chung focuses her study on how, in early reveals; one may appreciate the frankness with 1997, retired Army Sergeant Major Brenda which it is portrayed; one may embrace or reject Hoster came to accuse the Army’s top enlisted the conclusions and recommendations Chung man, Sergeant Major Gene McKinney—and the has given us. -

ABSTRACT POLITICAL (IN)DISCRETION: HILLARY CLINTON's RESPONSE to the LEWINSKY SCANDAL by Kelsey Snyder Through an Examination

ABSTRACT POLITICAL (IN)DISCRETION: HILLARY CLINTON’S RESPONSE TO THE LEWINSKY SCANDAL by Kelsey Snyder Through an examination of gender, politics, and media during the time of the Lewinsky scandal, this project shows that conversations about the first lady shifted throughout 1998. Just after the allegations were made public, the press and American people fought against the forthright position that Hillary took; the expectations of traditional first ladies they had known before were not met. After facing backlash via the press, the first lady receded to more acceptably defined notions of her actions, based largely in late 20th century conservative definitions of appropriate gender roles. By the end of 1998, consideration of a run for the Senate and increased public support for her more traditional image provided a compromise for Hillary Rodham Clinton’s public image. Having finally met the expectations of the nation, the press spoke less of the first lady in comparison to family values and almost exclusively by means of her political abilities. POLITICAL (IN)DISCRETION: HILLARY CLINTON’S RESPONSE TO THE LEWINSKY SCANDAL A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Department of History by Kelsey Snyder Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2015 Advisor __________________________________________ Kimberly Hamlin Reader ___________________________________________ Marguerite Shaffer Reader ___________________________________________ Monica Schneider TABLE OF CONTENTS -

Using Sentiment Analysis to Evaluate Administration-Press Relations from Clinton Through Trump Joshua Meyer-Gutbrod and John Woolley

POLITICAL COMMUNICATION https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1763527 New Conflicts in the Briefing Room: Using Sentiment Analysis to Evaluate Administration-press Relations from Clinton through Trump Joshua Meyer-Gutbrod and John Woolley Department of Political Science, University of California, Santa Barbara, California, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Journalists have argued that the high levels of hostility between American politics; executive President Trump and numerous media outlets have marked branch; media; presidency a critical juncture in presidential-press relations. This perceived con- flict challenges a key expectation of literatures on political media and the presidency: that functional interdependence will encourage pre- sidential administrations to tolerate more aggressive media question- ing in an effort to control media messages. We examine the interactions between U.S. presidential administrations and the White House press corps through thirty-five years of press briefing transcripts to assess the underpinnings of the current shift. We evaluate key hypotheses via a sentiment analysis using the NRC Emotional Lexicon. Generally, each side tends to reinforce, or mirror, positive and negative language of the counterparty during press briefings. However, we find a significant disjunction with the Trump Administration. Trump Administration representatives use negative language at higher rates than previous administrations and respond more sensitively to changes in press tone by decreasing positive language in response to press negativity. We discuss implications for the dynamic role of the media in shaping these changes. On November 7, 2018, the Trump Administration suspended the White House press pass of CNN Correspondent Jim Acosta, accusing Acosta of shoving a White House aide. Trump himself told Acosta, “You are a rude, terrible person. -

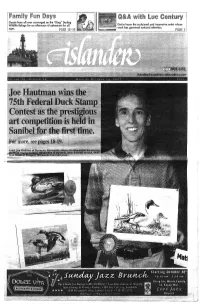

Va Islander.Coni

nir; Guests feurr c!i over cor.\fsrc<s6 or; ihe "Dirtj" Barling V'/iidiife ketuge i'-">r en cfse"~ocn cf adventure ?o: c'i I Os? {o iisiow Hie c.-cscinricd and ii;novf:five orris* whose v/crk has aarr.ered ntriio.iol ctferitio'i. va islander.coni Artist Joe Hautrrtan of Plymouth, Minnesota collects his bfue ribbon for winning the Duck Stamp Contest Harold Roe of Syfvania, Ohio finished second, while *^ot Sform of Freeport. Minnesota took third prize. - ! •. RESTAURANT 8r LOUNGE Local celebs show off footwork at WishMakers Ball '!• As the hit television show and former Ft. Myers Police Chief "Dancing With The Stars*' begins its Larry Hart. fall season, our local news personali- The evening will showcase a ties and community leaders are gear- silent auction of fantasy items it ing up for "Dancing With Our Stars" including an apartment overlooking Togo event. the Adriatic Sea, an Indy Car VIP tnc> Local celebrities will be compet- package and an autographed guitar What; ing at the 2007 WishMakers Ball — donated by rocker Sammy Hagar. 2007 WishMakers Ball © "where the magic of dance makes Other items on the auction block o wishes come true" — to benefit the include trips with airfare and VIP When: Make-A-Wish Foundation of tickets to the Masters Tournament, Saturday, Oct. 27 •E s Southern Florida. the 2008 Super Bowl, the British This second annual showcase and Open and California Wine Country. Where: Sanibei Harbour Resort and fa celebrity competition will be held on Last year's WishMakers Ball sold Saturday, Oct. -

Reagan, Congress, and the Fight Over the 1987 Federal Highway Bill

Arts & Humanities Open Access Journal Review Article Open Access Preventing roadkill: Reagan, congress, and the fight over the 1987 federal highway bill Introduction Volume 4 Issue 2 - 2020 The election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency represented the Samuel B Hoff beginning of a new era in American history. After decades of chief Department of History, Political Science, and Philosophy, executives who adhered to a liberal or moderate political philosophy, Delaware State University, George Washington Distinguished Reagan unabashedly advocated conservative principles. Wildavsky Professor Emeritus, USA views Reagan as1 “the first president since. Herbert Hoover...to favor Correspondence: Samuel B Hoff, George Washington limited government at home.” Bath and Collier contend that like Andrew Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Department of History, 2 Jackson, Reagan “led attacks on the government from the outside.” Political Science, and Philosophy, Delaware State University, USA, Shogan finds that Reagan’s personal experiences prior to being elected Email president (1992: 226) “gave him an aura of credibility” which in turn “helped him combine his ideology, values, and character into a Received: March 20, 2020 | Published: April 20, 2020 powerful force for presidential leadership.” The latter traits certainly influenced the legislative Reagan White House. Di Clerico determines that9 “Reagan’s smooth orientation and performance of the Reagan administration, start with Congress was a function not only of his astute political particularly -

Peter Roussel, Martha Joynt Kumar and Terry Sullivan, Houston, TX., November 3, 1999

White House Interview Program DATE: November 3, 1999 INTERVIEWEE: PETE ROUSSEL INTERVIEWER: Martha Kumar with Terry Sullivan [Disc 1 of 2] PR: —even though I was with [George] Bush for six years, in four different jobs. I was two years in the [Gerald] Ford White House, and 1981 to 1987 in the [Ronald] Reagan White House. I might add though, for your benefit, in neither case did I come in at the start. I came in under unusual circumstances in both cases. Maybe that’s something to look at, too, for people, because that’s always going to happen. TS: The notion of start is what we’re focused on, how the administration starts, but start has several definitions. Obviously, for a person who comes into the office it’s their start, whether it’s at the very beginning of the administration or later on in the administration. PR: Sure. TS: So those sorts of experiences are worthwhile as far as we’re concerned, as well. Some of the things we’re mostly interested in are: how the office works?, and things like⎯how do you know when it’s time to leave? What your daily life is like? And things like that. PR: That one I’m more than happy to address, having had the benefit of doing it twice. The second time, I was much more prepared to answer that question than the first time, which most people don’t get a second— TS: ⎯chance at. PR: Yes. Didn’t y’all interview my colleague, Larry Speakes? MK: Speakes and [Ron] Nessen as well. -

Course: Global Conversation I & II

Header Page top n Global Conversation I & II o i t a g i v a Edit N Washington: A Global Conversation This "Meta Moodle Page" is the joint program and course organization and Edit managment page for the three 6 credit components of the 2016 Washigton DC Off Campus Studies program. These include: POSC 288 Washington: A Global Conversation I POSC 289 Washington: A Global Conversation II POSC 293 Global Conversation, Internshp (6 credit) You should be registered for all three classes! Edit Health and Safety in DC Edit Health and Safety in DC To conserve space on the page, this content has been moved to a sub-page Edit Academic Components of the DC Experience In the sections below you will see a list of speakers, events, site visits etc. that will occupy our Wednesday and Fridays over the program. Associated with these events are important academic duties. INTERNSHIP AND PROGRAM JOURNAL Each week every student must upload a 'journal entry' consisting of a roughly 500 words (MS Word or pdf document) with two parts. Part 1 will address the student's experience in their internship activity. Part 2 will reflect on the speakers or site visits of the past week. Both of these section are open with regard to subject. For your final expanded journal entry of around 1000 words, which is due before June 3, you should reflect analytically on each of the two parts of your journals over the term and answer the following questions: 1. How did your internship inform the conversations with speakers? 2.