Society and Its Purposeb.Qxd:Rosmini Volume 1.Qxd 1/9/10 15:09 Page 1 a N T O N I O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1 Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by William Butler Yeats This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry Author: William Butler Yeats Editor: William Butler Yeats Release Date: October 28, 2010 [EBook #33887] Language: English Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FAIRY AND FOLK TALES *** Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Brian Foley and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) FAIRY AND FOLK TALES OF THE IRISH PEASANTRY. EDITED AND SELECTED BY W. B. YEATS. THE WALTER SCOTT PUBLISHING CO., LTD. LONDON AND FELLING-ON-TYNE. NEW YORK: 3 EAST 14TH STREET. INSCRIBED TO MY MYSTICAL FRIEND, G. R. CONTENTS. THE TROOPING FAIRIES-- PAGE The Fairies 3 Frank Martin and the Fairies 5 The Priest's Supper 9 The Fairy Well of Lagnanay 13 Teig O'Kane and the Corpse 16 Paddy Corcoran's Wife 31 Cusheen Loo 33 The White Trout; A Legend of Cong 35 The Fairy Thorn 38 The Legend of Knockgrafton 40 A Donegal Fairy 46 CHANGELINGS-- The Brewery of Egg-shells 48 The Fairy Nurse 51 Jamie Freel and the Young Lady 52 The Stolen Child 59 THE MERROW-- -

Balgooyen's Fate at SJSU in Limbo

rit SPARTAN DA 1 LY Vol. 97, No. 17 Published for San lose State University since 1934 Wednesday, September 25, 1991 Balgooyen's fate at SJSU in limbo By Tony Marek Court records. reversal of the decision went to independent Lismissal is too strong a punishment, Daily staff wnter But the university could provide no com- arbitration earlier this year, Balgooyen said according to professor David Elliott, chair 'I feel the sanction the ments on the status of the case other than to Tuesday. of the department of communication studies Biology professor Thomas Balgooyen's confirm that Balgooyen is still a faculty Final arguments have been filed by the and a family friend who has been following university seeks to apply future at SJSU may be decided this week, member, according to Lori Stahl, public faculty union and SJSU with a professional the proceedings since federal charges were following Thomas according to sources at the California information officer for SJSU. arbitrator, Kathy Kelly. filed in April, 1990. Balgooyen's conviction is Faculty Association who asked not to be Following his conviction, Balgooyen was Balgooyen said he was unable to com- "I feel the sanction the university seeks to too severe' named. notified by the university of its intention to ment on the current status of his appeal but apply following Thomas Balgooyen's con- Balgooyen, a SJSU biology professor, dismiss the tenured professor as of Jan. I, did say that he would want to continue viction is too severe," Elliott said. "It does was convicted in June, 1990 of illegally cap- 1991. -

STEVIE NICKS Stand Back

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] STEVIE NICKS Stand Back Die ultimative Stevie Nicks-Sammlung anlässlich des zweiten Rock and Roll Hall Of Fame -Entrys der Songwriting-Ikone Der sensationelle Querschnitt durch STEVIE NICKS‘ gesamten Solo-Katalog! In diesem Frühjahr über Rhino auf 3-CD, 1-CD, 6-LP Vinyl und in allen digitalen Formaten! STEVIE NICKS schreibt Geschichte: Als erste Frau wird die beliebte und bewunderte Songwriterin zum zweiten Mal in die Rock and Roll Hall Of Fame aufgenommen! Das erste Mal 1998 als Mitglied von Fleetwood Mac; im März dieses Jahres wird sie für ihre außergewöhnliche Solokarriere, die sie seit 40 Jahren konstant verfolgt, in den renommierten Club aufgenommen. Um die bahnbrechenden Verdienste NICKS´ zu ehren, hat Rhino nun einige neue Releases zusammengestellt, die ihre Solokarriere mit essenziellen Aufnahmen feiert. Sie stammen aus ihren Studioalben, aus Live-Performances und Soundtrack-Beiträgen sowie einigen ihrer berühmtesten Kollaborationen mit Tom Petty & Heartbreakers, Don Henley, Lana del Rey und Lady Antebellum. Stand Back wird über Rhino in verschiedenen Konfigurationen veröffentlicht: Am 29. März erscheint eine Sammlung von 18 Tracks auf Einzel-CD sowie zum Download und als Stream. Am 19. April kommt die opulente Sammlung Stand Back: 1981-2017 mit 50 Tracks auf 3 CDs und am 28. Juni erscheint das volle Paket auf 6 LPs! Sechs Jahre nach ihrem Einstieg bei Fleetwood Mac, im Jahr 1981, überraschte STEVIE NICKS mit ihren Solo- Debüt Bella Donna. Es wurde ein Riesenerfolg, verkaufte fünf Millionen Exemplare allein in den USA, toppte die US- Albumcharts und enthielt fünf Hit-Singles, darunter die weltbekannte Hymne Edge Of Seventeen. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

NEW RELEASE GUIDE January 8 January 15 ORDERS DUE DECEMBER 04* ORDERS DUE DECEMBER 11*

ada–music.com @ada_music NEW RELEASE GUIDE January 8 January 15 ORDERS DUE DECEMBER 04* ORDERS DUE DECEMBER 11* 2020 ISSUE 2 *2020 date January 8 ORDERS DUE DECEMBER 04* *2020 date DELUXE VERSIONS FEATURE 10 BONUS ACOUSTIC TRACKS ALL PACKAGING IS MADE FROM 100%RECYCLED MATERIAL & THE WRAP AND STICKER IS BIODEGRADABLE Street Date: 01/08/2021 Hailing from Brighton, England, Passenger is a multi-award winning, platinum-selling singer- File Under: Singer-Songwriter songwriter. Although still known for his busking, he long ago made the journey from street corners Format: CD/2CD (Deluxe)/2LP/Digital to stadiums, thanks in part to supporting his good mate Ed Sheeran, and most notably with TRACKLISTING: which reached number 1 in 19 countries and is approaching three billion plays 1. Sword From The Stone “Let Her Go,” 2. Tip Of My Tongue on YouTube. Yet ‘Let Her Go’ is just one song from a remarkable and prolific back catalogue, 3. What You’re Waiting For including 2016’s Young as the Morning, Old as the Sea, which topped the charts in the UK and 4. The Way That I Love You beyond. The consistency of his output, coupled with his authenticity both on and off stage, has 5. Remember To Forget 6. Sandstorm won Passenger a dedicated fanbase around the globe. 7. A Song For The Drunk and Broken Hearted The majority of Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted was written when Rosenberg was 8. Suzanne newly single. “Coming out of a break-up creates such a fragile window,” he reflects.“You’re 9. -

50Th B-Day Playlist

Page 1 of 20 50th B-day 672 songs, 1.8 days, 4.59 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Dancing Queen 3:52 Gold ABBA 2 Take A Chance On Me 4:04 Gold ABBA 3 Mamma Mia 3:33 Gold ABBA 4 Ride On 5:54 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC 5 Money Talks 3:46 The Razor's Edge AC/DC 6 New York Groove 3:04 Kiss: Ace Frehley (Remastered) Ace Frehley 7 Sweet Emotion 4:34 Toys In The Attic Aerosmith 8 Eye In The Sky 4:37 The Essential Alan Parsons Project The Alan Parsons Project 9 Black Velvet 4:49 Alannah Myles Alannah Myles 10 City Of New Orleans 4:33 The Best Of Arlo Guthrie Arlo Guthrie 11 Heat Of The Moment 3:55 Asia Asia 12 Turn Up the Radio 4:39 Sign In Please Autograph 13 The Thrill Is Gone 5:28 Greatest Hits B.B. King 14 Better Not Look Down 4:15 Thelma & Louise B.B. King 15 The Weight 4:35 The Best Of The Band The Band 16 Manic Monday 3:06 Different Light The Bangles 17 If She Knew What She Wants 3:50 Different Light The Bangles 18 I'll Set You Free 4:51 Greatest Hits The Bangles 19 Main Title 3:22 Quigley Down Under Basil Poledouris 20 Stand By Me 2:57 The Very Best Of Ben E. King Ben E. King 21 In The Street 2:55 #1 Record/Radio City Big Star 22 Dancing With Myself 4:50 Greatest Hits Billy Idol 23 Cradle Of Love 4:39 Greatest Hits Billy Idol 24 Hot In The City (Exterminator Mix) 5:10 Vital Idol Billy Idol 25 Keeping The Faith 4:39 Greatest Hits Volume III Billy Joel 26 We Didn't Start The Fire 4:49 Greatest Hits Volume III Billy Joel 27 My Life 3:52 Greatest Hits, Vol. -

A Study of Yeats's Poetic Discourse Versus the Concept of History

Maria Camelia Dicu THE WORLD IN ITS TIMES. A STUDY OF YEATS’S POETIC DISCOURSE VERSUS THE CONCEPT OF HISTORY Maria Camelia Dicu THE WORLD IN ITS TIMES. A STUDY OF YEATS’S POETIC DISCOURSE VERSUS THE CONCEPT OF HISTORY Maria Camelia Dicu THE WORLD IN ITS TIMES. A STUDY OF YEATS’S POETIC DISCOURSE VERSUS THE CONCEPT OF HISTORY EUROPEAN SCIENTIFIC INSTITUTE, Publishing Impressum Bibliographic information published by the National and University Library "St. Kliment Ohridski" in Skopje; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://www.nubsk.edu.mk/; CIP - 821.111(417).09 COBISS.MK-ID 95022602 Any brand names and product names mentioned in this book are subject to trademark, brand or patent protection and trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders. The use of brand names, product names, common names, trade names, product descriptions etc. even without a particular marking in this works is in no way to be construed to mean that such names may be regarded as unrestricted in respect of trademark and brand protection legislation and could thus be used by anyone. Publisher: :European Scientific Institute Street: "203", number "1", 2300 Kocani, Republic of Macedonia Email: [email protected] Printed in Republic of Macedonia ISBN: 978-608-4642-09-1 Copyright © 2013 by the author, European Scientific Institute and licensors All rights reserved. Kocani 2013 THE WORLD IN ITS TIMES. A STUDY OF YEATS’S POETIC DISCOURSE VERSUS THE CONCEPT OF HISTORY Maria CAMELIA DICU December, 2013 Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 1. Yeats’s Biography as an Anglo-Irish Artist ............................................................. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title (Aerosmith) 02)Nwa 10 Years I Dont Wanna Miss A Thing Real Niggas Don't Die Through The Iris (Busta Rhymes Feat Mariah 03 Waking Up Carey) If You Want Me To Stay Wasteland I Know What You Want (Remix) 100% Funk (Ricky Martin) 04 Play That Funky Music White Living La Vida Loca Behind The Sun (Ben Boy (Rose) Love Songs Grosse Mix) 101bpm Ciara F. Petey Eric Clapton - You Look 04 Johnny Cash Pablo Wonderful Tonight In The Jailhouse Goodies Lethal Weapon (Soplame.Com ) 05 11 The Platters - Only You Castles Made Of Sand (Live) Police Helicopter (Demo) (Vitamin C) 05 Johnny Cash 11 Johnny Cash Graduation (Friends Forever) Ring Of Fire Sunday Morning C .38 Special 06 112 Featuring Foxy Brown Caught Up In You Special Secret Song Inside U Already Know [Huey Lewis & The News] 06 Johnny Cash 112 Ft. Beanie Sigel I Want A New Drug (12 Inch) Understand Your Dance With Me (Remix) [Pink Floyd] 07 12 Comfortably Numb F.U. (Live) Nevermind (Demo) +44 07 Johnny Cash 12 Johnny Cash Baby Come On The Ballad Of Ir Flesh And Blood 01 08 12 Stones Higher Ground (12 Inch Mix) Get Up And Jump (Demo) Broken-Ksi Salt Shaker Feat. Lil Jon & Godsmack - Going Down Crash-Ksi Th 08 Johnny Cash Far Away-Ksi 01 Johnny Cash Folsom Prison Bl Lie To Me I Still Miss Som 09 Photograph-Ksi 01 Muddy Waters Out In L.A. (Demo) Stay-Ksi I Got My Brand On You ¼‚½‚©Žq The Way I Feel-Ksi 02 Another Birthday 13 Hollywood (Africa) (Dance ¼¼ºñÁö°¡µç(Savage Let It Shine Mix) Garden) Sex Rap (Demo) 02 Johnny Cash I Knew I Loved You 13 Johnny Cash The Legend -

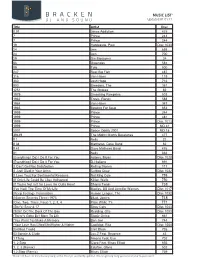

Combined Song List

B R ACKEN MUSIC LIST* D J AND SOUND Updated 01.01.11 Title Artist Disc 0.01 Janes Addiction 425 7 Prince 243 7 Prince 244 19 Hardcastle, Paul Disc 1033 24 Jem 658 24 Jem 700 29 Gin Blossoms 34 86 Greenday 584 99 Toto 500 247 Reel Big Fish 487 316 Van Halen 119 360 Josh Hoge 716 900 Breeders, The 361 1251 The Strokes 82 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 503 1982 Travis, Randy 588 1984 Van Halen 347 1985 Bowling For Soup 653 1999 Prince 244 1999 Prince 481 1999 Prince Disc 1013 1999 Prince MD 41 2001 Space Oddity 2001 MD 18 39449 The Mighty Mighty Bosstones 477 # 1 Nelly 22 # 34 Matthews, Dave Band 62 # 41 Dave Mathews Band 476 #1 Nelly 664 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Adams, Bryan Disc 1028 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You DJ Italiano 691 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 117 (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew Disc 1032 (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole 755 (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells 750 (If You're Not in It for Love) I'm Outta Here! Shania Twain 738 (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Medley, Bill And Jennifer Warnes Disc 1017 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League, The Disc 1032 (Ninteen Seventy Three) 1973 Blunt, James 748 (One, Two, Three, Four) 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's 771 (She's) Sexy & 17 Stray Cats Disc 1043 (Sittin' On)The Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis Disc 1003 (There's Gotta Be) More To Life Stacie Orrico 661 (You Want To) Make A Memory Bon Jovi 744 (Your Love Has Lifted Me)Higher & Higher Coolidge, Rita Disc 1054 [Untitled Track] Clint Black 735 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z Feat. -

Solving Practical Problems for Independent Living. Utah Home Economics and Family Life Curriculum Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 700 CE 069 578 TITLE Life Management: Moving Out! Solving Practical Problems for Independent Living. Utah Home Economics and Family Life Curriculum Guide. INSTITUTION Utah State OLEice of Education, Salt Lake City. PUB DATE Aug 92 NOTE 511p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC21 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; Clothing; *Daily Living Skills; *Family Life Education; *Home Economics; Housing; *Interpersonal Competence; Leadership; Learning Activities; Lesson Plans; Life Style; Marriage; Money Management; Nutrition; Parenthood Education; *Problem Solving; Purchasing; Resources; Secondary Education; State Curriculum Guides; *Thinking Skills; Transportation; Values IDENTIFIERS Goal Setting; *Utah ABSTRACT This guide, which has been developed for Utah's home economics and family life education program, contains materials for use in teaching a life management course emphasizing the problem-solving skills required for independent living. Discussed first are the assumptions underlying the curriculum, development of the guide, and suggestions for its use. The remainder of the guide consists of materials for use in teaching units on the following topics: course overview, values and goals, relationships, life roles, resources, the process of practical reasoning, choosing a place to live, meeting transportation needs, managing finances, planning food for optimum health, selecting and caring for clothing, preparing for marriage, thinking about parenthood, and leadership. Each unit contains some or all of the following: unit objectives; unit outline listing the life essential/skill and subproblem(s) covered, unit value assumption, unit objective, and topics of the unit's lessons; resource list cross-referencing student handouts, teacher materials/information sheets, and transparency masters for each lesson; and unit lessons. -

1983 Fleetnotes Via Fmlegacy ! May 27, 1983 – Las Vegas, NV !Joe Walsh Opened for Stevie May 30, 1983 –San Bernardino, CA Performed at the US Fes�Val

1983 Fleetnotes via FMLegacy ! May 27, 1983 – Las Vegas, NV !Joe Walsh opened for Stevie May 30, 1983 –San Bernardino, CA Performed at the US Fes7val. Big surprise was her singing ‘Angel’ and ‘Gold and Braid’. Bootleg is !circulang. Gold Dust Woman Outside the Rain Dreams Gold and Braid I Need To Know Gypsy Angel Leather and Lace Stand BacK How S7ll My Love Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around Edge of Seventeen !Rhiannon June 21, 1983 – Knoxville, TN !Joe Walsh opened for Stevie June 23, 1983 – Norfolk, VA !Joe Walsh opened for Stevie June 24, 1983 – East Rutherford, NJ Stevie’s record company had an orchestra play and Paul BucKmaster flown in to conduct on Beauty & The Beast. During the middle of Rhiannon a fan jumped on stage KnocKing Stevie to the ground. When she got up she said that in 9 years of touring with Fleetwood Mac that had never happened !before. She did not finish the song either. Joe Walsh opened for Stevie. Bootleg is circula7ng. Gold Dust Woman Outside the Rain Dreams Gold and Braid I Need To Know Sara Enchanted If Anyone Falls Leather & Lace Stand BacK Beauty and the Beast Gypsy How S7ll My Love Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around Edge of Seventeen Rhiannon ! June 27, 1983 – Philadelphia, PA !Joe Walsh opened for Stevie. Bootleg is circula7ng. Gold Dust Woman Outside the Rain Dreams Gold and Braid I Need To Know Angel If Anyone Falls Leather & Lace Stand BacK Beauty and the Beast Gypsy How S7ll My Love Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around Edge of Seventeen !Rhiannon June 28, 1983 – PiOsburgh, PA Sara was dropped for Angel. -

Stephanie Lynn Nicks, 1976

Stephanie Lynn Nicks, 1976 20494_RNRHF_Text_Rev1_22-61.pdf 25 3/11/19 5:23 PM > >Stevie HER DAZZLING SOLO CAREER HAS PROVIDED AN OUTLET FOR HER PROLIFIC SONGWRITING AND BOUNTIFUL CREATIVITY NicksBY PARKE PUTERBAUGH A tevie Nicks’ life and career have always had a served from condescending, patrician rock critics who touch of magical enchantment. Tonight rep- dismissed her as flighty. “Stevie Nicks: Gifted Dreamer or resents a crowning validation of her spellbind- Air Head’s Delight?” read the headline of a typical review. ing gifts as a rock & roll icon, as she becomes Feminism has come a long way since the early 1980s. the first woman to be twice inducted into the Hell, feminism has come a long way in just the past year. Rock & Roll Hall of Fame – with Fleetwood If Nicks’ dreamy, daring solo albums had come out to- Mac in 1998, and now as a solo artist. day, they would’ve certainly received a warmer overall The solo career of Stephanie “Stevie” Nicks (born May reception from reviewers. Not that it mattered – each 26, 1948, in Phoenix) derived from the almost enviable sold hugely and charted highly, earning accolades in the frustration of belonging to a band with three sterling song- court of public opinion. It’s sufficient to note that some of writers. On Fleetwood Mac’s gem-packed albums, Nicks the estimable artists who followed in Nicks’ wake – Tori had to compete for space with guitarist Lindsey Buck- Amos, Courtney Love, Lorde, and Haim, to name just a ingham and keyboardist Christine McVie. When drum- few – cite her as a key inspiration and influence.