Is Ultimate Reality Unlimited Love?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty-Two Thoughts on Deep Value Investing

Twenty-two Thoughts on Deep Value Investing By J. Ellwood Towle July 2018 Deep value investing is expressed in various ways. In this commentary, deep value investing represents the learnings and insights gained during my nearly four decades as an investment professional. Other investors will likely have differing views. 1. Deep value investing is predicated on two fundamental beliefs: trusting in the goodness and decency of mankind and recognizing that economic progress is on- going, inevitable. 2. Deep value has been enlightened through the ideas and actions of Warren Buffett, Benjamin Graham, and John Templeton. Deep value investing is a timeless capital creating strategy. 3. Effective deep value investing takes time, likely many decades. Benefits will occur to those who compound their capital at meaningful rates of return. Patience and perseverance are key ingredients in this long term, capital creating journey. 4. By nature, deep value is more volatile than most long only, public equity strategies. At times, it will produce disappointing, short term results in an investment world that desires predictable and improving short term performance. However, it is the cyclicality and volatility of deep value that creates investment opportunity. 5. Knowing when to buy or sell is the “art” of deep value. Contrarian thought is a necessity. John Templeton says it best, “To buy when others are despondently selling and to sell when others are greedily buying requires the greatest fortitude, even while offering the greatest reward.” (Doubleday & Company 1983) 6. The gathering of the data is the “science” of deep value. Fact finding may require research and contacts beyond published data and readily available information. -

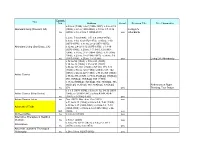

List of New Thought Periodicals Compiled by Rev

List of New Thought Periodicals compiled by Rev. Lynne Hollander, 2003 Source Title Place Publisher How often Dates Founding Editor or Editor or notes Key to worksheet Source: A = Archives, B = Braden's book, L = Library of Congress If title is bold, the Archives holds at least one issue A Abundant Living San Diego, CA Abundant Living Foundation Monthly 1964-1988 Jack Addington A Abundant Living Prescott, AZ Delia Sellers, Ministries, Inc. Monthly 1995-2015 Delia Sellers A Act Today Johannesburg, So. Africa Association of Creative Monthly John P. Cutmore Thought A Active Creative Thought Johannesburg, So. Africa Association of Creative Bi-monthly Mrs. Rea Kotze Thought A, B Active Service London Society for Spreading the Varies Weekly in Fnded and Edited by Frank Knowledge of True Prayer 1916, monthly L. Rawson (SSKTP), Crystal Press since 1940 A, B Advanced Thought Journal Chicago, IL Advanced Thought Monthly 1916-24 Edited by W.W. Atkinson Publishing A Affirmation Texas Church of Today - Divine Bi-monthly Anne Kunath Science A, B Affirmer, The - A Pocket Sydney, N.S.W., Australia New Thought Center Monthly 1927- Miss Grace Aguilar, monthly, Magazine of Inspiration, 2/1932=Vol.5 #1 Health & Happiness A All Seeing Eye, The Los Angeles, CA Hall Publishing Monthly M.M. Saxton, Manly Palmer Hall L American New Life Holyoke, MA W.E. Towne Quarterly W.E. Towne (referenced in Nautilus 6/1914) A American Theosophist, The Wheaton, IL American Theosophist Monthly Scott Minors, absorbed by Quest A Anchors of Truth Penn Yan, NY Truth Activities Weekly 1951-1953 Charlton L. -

Sir John M. Templeton Has Passed Away

Zagadnienia Filozoficzne POŻEGNANIE w Nauce XLIII (2008) SIR JOHN M. TEMPLETON NIE ŻYJE Dnia 8 lipca 2008 r. w szpitalu w Nassau (Bahamy), w wieku lat 95, zmarł Sir John M. Templeton. Poniżej przedrukowujemy tekst zamieszczony z tej okazji na stronach internetowych Fundacji Johna Templetona <http://www.sirjohntempletonobituary.org/>. July 8, 2008 Sir John Templeton, Pioneer Investor and Philanthropist John Marks Templeton, the pioneer global investor who founded the Templeton Mutual Funds and for the past three decades devoted his fortune to his Foundation’s work on the “Big Questions” of science, religion, and human purpose, passed away on July 8, 2008, at Doctors Hospital in Nassau, Bahamas, of pneumonia. As a pioneer in both financial investments and philanthropy, John Templeton spent a lifetime encouraging open-mindedness. If he hadn’t sought new paths, he once said, “he would have been unable to attain so many goals.” The motto that Templeton created for his Foundation, “How little we know, how eager to learn”, exemplified his philosophy in the financial markets and his groundbreaking methods of philan- thropy. Templeton started his Wall Street career in 1937 and went on to create some of the world’s largest and most successful international investment funds. Called by Money magazine “arguably the greatest global stock picker of the century” (January 1999), he sold the Tem- pleton Funds in 1992 to the Franklin Group for $440 million. A naturalized British citizen who lived in Nassau, the Bahamas, Templeton was created a Knight Bachelor by Queen Elizabeth II in 4 Pożegnanie 1987 for his many philanthropic accomplishments, including his en- dowment of the former Oxford Centre for Management Studies as a full college, Templeton College, at the University of Oxford in 1984. -

16 Rules for Investment Success

16 RULES FOR INVESTMENT SUCCESS And for your family, house, tuition, retirement… By Sir John Templeton I can sum up my message by reminding you of Will Rogers’ famous advice. “Don’t gamble,” he said. “ Buy some good stock. Hold it till it goes up…and then sell it. If it doesn’t go up, don’t buy it!” There is as much wisdom as humor in this remark. Success in the stock market is based on the principle of buying low and selling high. Granted, one can make money by reversing the order—selling high and then buying low. And there is money to be made in those strange animals, options and futures. But, by and large, these are techniques for traders and speculators, not for investors. And I am writing as a professional investor, one who has enjoyed a certain degree of success as an investment counselor over the past half-century—and who wishes to share with others the lessons learned during this time. The rules and guidance discussed in this piece are for educational purposes only; should not be considered investment advice or an investment recommendation; and will not guarantee an investor positive investment results or protect against market loss. Investing in a Franklin Templeton fund cannot guarantee one’s financial goals will be met. Please consult your financial professional for personalized advice tailored to your specific goals, individual situation and risk tolerance. The article first appeared in 1993 inWorld Monitor: The Christian Science Monitor Monthly, which is no longer published, and is reprinted with permission of the John Templeton Foundation. -

Recommended Unity Readings!

Unity of Greater Hartford – www.unityhartford.org Recommended Unity Readings! NOTE: Many of the Fillmore books are available for free as Unity co-founders Charles and Myrtle Fillmore did not copywrite their publications/books. Unity Principles ➢ The Five Principles – Ellen Debenport - The Five Principles provides tools for daily living and is an easy-to-read explanation of Unity’s basic teachings. ➢ Unity: A Quest for Truth – Eric Butterworth - "Unity today is dedicated to the open mind, to the continuous quest for Truth. It seeks not to tell you what to think, how to define God, what creeds to accept. Unity seeks only to teach you how to think, how to pray--so that you can formulate your own definition of God, experience your own communion with God, and find your own distinctly personal revelation of Truth." ➢ Lessons in Truth – H. Emilie Cady - Lessons in Truth is a clear, concise representation of New Thought philosophy and metaphysical Christianity. The spiritual concepts presented in these twelve lessons show us how to increase our personal empowerment and enhance our spiritual growth. This has been the foundational book since the beginning of Unity. Bible Study ➢ The Revealing Word – A Dictionary of Metaphysical Terms - This special dictionary written by Unity co-founder Charles Fillmore contains metaphysical meanings of 1200 words and phrases that are frequently used in Unity publications and the Bible. The inner interpretations found in The Revealing Word can be applied to everyday living. Child/Family ➢ I Believe in Me - Whimsical animals, characters, and angels illustrate, in full color, twenty-seven affirmations that will inspire you, the child you love, and the child within all of us. -

Mystical Experiences, Neuroscience, and the Nature of Real…

MYSTICAL EXPERIENCES, NEUROSCIENCE, AND THE NATURE OF REALITY Jonathan Scott Miller A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2007 Committee: Marvin Belzer, Advisor Kenneth I. Pargament Graduate Faculty Representative Michael Bradie Sara Worley ii © 2007 Jonathan Miller All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Marvin Belzer, Advisor Research by neuroscientists has begun to clarify some of the types of brain activity associated with mystical experiences. Neuroscientists disagree about the implications of their research for mystics’ beliefs about the nature of reality, however. Persinger, Alper, and other scientific materialists believe that their research effectively disproves mystics’ interpretations of their experiences, while Newberg, Hood, and others believe that scientific models of mystical experiences leave room for God or some other transcendent reality. I argue that Persinger and Alper are correct in dismissing mystics’ interpretations of their experiences, but that they are incorrect in asserting mystical experiences are pathological or otherwise undesirable. iv To Betty, who knows from experience. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Special thanks are due to all the members of my committee, for their extreme patience, both when I was floundering about in search of a topic, and when my work had slowed to a trickle after an unexpected and prolonged illness. I feel especially fortunate at having been able to assemble a committee in which each of the members was truly indispensable. Thanks to Ken Pargament for his world-class expertise in the psychology of religion, to Mike Bradie and Sara Worley for their help with countless philosophical and stylistic issues, and to Marv Belzer, for inspiring the project in the first place, and for guiding me through the intellectual wilderness which I had recklessly entered! vi TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. -

Updated August 20, 2019 Angela Lee Duckworth University Of

Updated August 20, 2019 Angela Lee Duckworth University of Pennsylvania 3401 Market St., Suite 202 Philadelphia, PA 19104 Education UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA (2002–2006) MA, PhD in Psychology UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD (1994–1996) MSc with Distinction in Neuroscience HARVARD COLLEGE (1988–1992) AB magna cum laude in Advanced Studies Neurobiology Positions Held Founder and CEO, Character Lab (2015–current) Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania (2016– current) Faculty Co-Director, Behavior Change for Good (2017-current) Faculty Co-Director of Wharton People Analytics, University of Pennsylvania (2015–current) Secondary Appointment at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania (2016–current) Secondary Appointment at the Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania (2015– current) Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania (2015–2016) Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania (2013–2015) Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania (2007–2013) Research Associate, Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania (2006–2007) Science Teacher, Mastery Charter High School, Philadelphia, PA (2002) Chief Operating Officer, GreatSchools.net (2000–2001) Math Teacher, Lowell High School (1998–2000) Math Teacher, The Learning Project (September 1997–June 1998) 1 Updated August 20, 2019 Management Consultant, McKinsey & Company (October 1996–August 1997) Fellow, Center for the Enhancement of Science and Math -

Religions of the World - an Overview

Religions of the World - an overview What are the major religions of the world? Judaism Hinduism Christianity Buddhism Islam Sikhism Baha’i Faith Jainism Taoism / Daoism Zoroastrianism Confucianism Shinto Categorizing Religions: - Ethnic vs. Universal Ethnic: the religion of a particular people or culture (e.g., Judaism, Shinto, Hinduism) tend to be localized and do not actively seek converts) Universal: a religion which sees its message as true for all people (e.g., Christianity, Islam, Buddhism) have spread throughout the world and tend to be very large in population, have actively sought converts from many cultures) Categorizing Religions: - Theistic vs. Non-theistic Theistic: focus on a personal God (mono-) or gods (poly-) (god = supernatural "person,” spirit being) (most common in western religions) Non-theistic: Ultimate Reality or ultimate goal of the religion does not involve a personal god (impersonal Ultimate Reality) (force or energy) (found mostly in the eastern religions) Categorizing Religions: - Major vs. Minor Major religions: Religions that are high in population, widespread throughout the world, the basis upon which other religions were built and/or otherwise highly influential Minor Religions: Religions that are limited in population, geographic locale and/or influence Categorizing Religions: - Western vs. Eastern Western: Religions Eastern: Religions that developed west that developed east of the Urals (e.g. in of the Urals (e.g., in the Near East and India, China and Europe): Japan) Judaism Far East Christianity -

Religious Studies Paper

Name Tutor RPE Class RPE Teacher Homework Your homework is to revise the key knowledge for this unit. • You will have a banded assessment and a knowledge quiz at the HWK Completed: Score: end of this unit. 1 2 • Your grade and score will reflect how well you have revised during the term. 3 4 • This booklet contains fortnightly revision activities that you must 5 complete to prepare. 6 7 • This booklet must be brought in for your teacher to see on the 8 homework due date. • All answers are on the knowledge organiser. Overall Score: • The activities will be marked in class on the homework due date. Overall Percentage: • Atman: The eternal spirit inside • Hinduism: Gets its name from • Sanskrit: Ancient Indian every living being, part of the the River Indus in India where language many of the scripture ultimate being. Hinduism began. is written in. • Aum: A sacred sound that is • Hindu: A follower of the religion • Shaiva: A Hindu who believes important to Hindus which they Hinduism. that Shiva is the supreme God. chant. • Karma: That all actions have • Shiva: The destroyer and re- • Avatar: When a god takes the consequences. Good actions = creator. form of an animal or a human good consequences. Bad • Supreme: The best or greatest. and comes to earth to fight evil actions = bad consequences. • Symbol: An image that and establish peace and • Moksha: Where a Hindu is freed expresses religious ideas. harmony. from samsara and back with • Trimurti: A term for the three • Brahma: The creator. Brahman. main Hindu gods Brahma, • Brahman: Many Hindus believe • Monotheist: Someone who Vishnu and Shiva. -

Count on the Margin of Safety

Cover Story COUNT ON THE Times have changed since Benjamin Graham wrote the Security Analysis but his principles can hold investors in good stead even now N Mahalakshmi & Mohammed Ekramul Haque t cannot be denied that the Great safety’, allowing for any contraction in grabbed the attention of several pro- Depression of 1929 and the Wall prices, were his key bets. fessional investors, many of who have Street crash that followed was per- His strategy soon started being talk- added their own perspectives over the Ihaps the most humbling experi- ed about in the investing community. following decades. Nevertheless, the ence for investors at the time. Life was One man, in particular, was highly in- basic essence of value investing has tough and there was no hope to clutch fl uenced by Graham’s strategy, and remained the same: buy cheap. on to. After crushing losses, most in tribute to his ‘idol’, bought shares It was a philosophy that was born stocks were available at ridiculously in about a hundred such cheap com- in desperate times (the Depression cheap prices over the next decade as panies. His faith soon paid off: in fi ve years), and underwent a baptism by the markets remained trapped in a years, John Templeton – whose name fi re as it was tested time and again over bear grip. today is synonymous with value the next few years. But as any stock expert will tell you investing – had multiplied his So it wouldn’t be wrong to wonder today, behind every market disaster original investment several times, just a little bit whether those princi- lurks opportunity – if you just look despite around 15 of those companies ples still work in today’s times, given hard enough. -

Title Current Sub. Holdings Keep? Previous Title Title

Current Title Sub. Holdings Keep? Previous Title Title Changed to v.5:no.2 (1995); v.6-7 (1996-1997); v.8:no.2-12 Abundant living (Prescott, AZ) (1998); v.9-12 (1999-2002); v.13:no.1-7, 9-12 Living Life no (2003); v.14- 21:no.1 (2004-2011) yes Abundantly v.4:no. 7-10 (1968); v.5- v.8 (1968-1972); v.9:no. 1-10, 12 (1972-1973); v.10:no. 1-10 (1973-1974); v.11:no. 2-12 (1974-1975); Abundant Living (San Diego, CA) v.12:no. 2,4-9,11-12 (1975-1976); v.13-19 (1976-1983); v.20:no. 1-7, 9-10, 12 (1983- 1984); v.21:no. 3-11 (1984-1985); v.22 (1985- 1986); v.23:no. 1-8 (1986-1987); v.24:no. 1-6 no (1987-1988); v.25:no. 1-4 (1988) yes Living Life Abundantly v.52:no.56 (1944); v.53:no.63 (1945); v.54:no.74 (1946); v.55:no.93 (1947); v.56:no.101-102 (1948); v.57:109, 115, 120 (1949); v.58:no.128 (1950); v.59:no.137, 142 (1951); v.66:no.227 (1958); v.73:no.308 (1965); Active Service v.75:no.335 (1967); v.77:no.354[Sup], 355[Sup], 356, 357[Sup], 358[Sup], 359 (1969); v.78:no.360[Sup]; 361[Sup], 362, 363[Sup], 365, 366[Sup], 367[Sup], 368, 369[Sup], 370[Sup], Reflections in Right no 371 yes Thinking, True Prayer v.1-v.5 (1974-1979); v.6:no.31-32, 34-36 (1979- Active Service (New Series) 1980); v.7 (1980-1981); v.8:no.43-44, 46-47 no (1981); v.9 (1982-1983) yes Active Service Letter no Dec (1971); Mar, Aug, Oct (1972) yes v.31:no.5-11 (1982); v.32:no.4-5, 7-23 (1983); v.33:no.1-17 (1983-1984); v.34:no.1-4, 7-13 Advocate of Truth (1984-1985); v.35:no.2-12 (1985-1986); v.36- Gift (1986- ) yes All-Seeing Eye no v.5:no.2-3 (1930) yes Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine no v.7:no.1 (2001) yes v.1:no.7-8, 10-11 (1977); v.2:no.2-7, 9-11 Alternatives no (1978); v.3:no.1-2 (1979) yes American Journal of Theology & Philosophy no v.28-v.33:no.3(2007-2012) yes Current Title Sub. -

Workshop on Moral Learning

WORKSHOP ON MORAL LEARNING May 15-17th, 2015 Michigan League, Ann Arbor, MI OBJECTIVE Recent years have witnessed dramatic growth in three areas of psychological and philosophical research: learning, decision-making, and moral judgment. It seems a good time to ask how these bodies of research might inform one another, and whether the outlines of a new synthesis in understanding moral psychology is beginning to become visible. For example, while there is important evidence that implicit, affect- laden processes are at work in moral judgment, research in affective science, behavioral economics, and learning theory suggests that such processes involve much more sophisticated information-processing mechanisms than previously thought, and that these mechanisms regulate choice and behavior in ways that approximate normative conceptions of decision-making and action developed by philosophers and cognitive scientists. This picture is strengthened by new research in developmental psychology, which suggests that infants early on have complex models of their social and physical environment, which update in response to experience. Perhaps the long- standing distinction between reason and emotion needs to be put into question, permitting a more integrated and normatively-interesting picture of moral learning and decision-making. At the same, however, there is a great deal of evidence that there are multiple implicit learning processes underlying intuitive moral evaluation, which can at times come into competition for the regulation of decision-making and action and can lead to choices that are defective from the standpoint of rational decision theory. Such competition among implicit learning processes might be able to explain some of the more paradoxical aspects of moral judgment, but it also raises challenges for assessing the normative standing of moral intuitions.