The Temple of Peace (Rome) Published on Judaism and Rome (

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9781107013995 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01399-5 — Rome Rabun Taylor , Katherine Rinne , Spiro Kostof Index More Information INDEX abitato , 209 , 253 , 255 , 264 , 273 , 281 , 286 , 288 , cura(tor) aquarum (et Miniciae) , water 290 , 319 commission later merged with administration, ancient. See also Agrippa ; grain distribution authority, 40 , archives ; banishment and 47 , 97 , 113 , 115 , 116 – 17 , 124 . sequestration ; libraries ; maps ; See also Frontinus, Sextus Julius ; regions ( regiones ) ; taxes, tarif s, water supply ; aqueducts; etc. customs, and fees ; warehouses ; cura(tor) operum maximorum (commission of wharves monumental works), 162 Augustan reorganization of, 40 – 41 , cura(tor) riparum et alvei Tiberis (commission 47 – 48 of the Tiber), 51 censuses and public surveys, 19 , 24 , 82 , cura(tor) viarum (roads commission), 48 114 – 17 , 122 , 125 magistrates of the vici ( vicomagistri ), 48 , 91 codes, laws, and restrictions, 27 , 29 , 47 , Praetorian Prefect and Guard, 60 , 96 , 99 , 63 – 65 , 114 , 162 101 , 115 , 116 , 135 , 139 , 154 . See also against permanent theaters, 57 – 58 Castra Praetoria of burial, 37 , 117 – 20 , 128 , 154 , 187 urban prefect and prefecture, 76 , 116 , 124 , districts and boundaries, 41 , 45 , 49 , 135 , 139 , 163 , 166 , 171 67 – 69 , 116 , 128 . See also vigiles (i re brigade), 66 , 85 , 96 , 116 , pomerium ; regions ( regiones ) ; vici ; 122 , 124 Aurelian Wall ; Leonine Wall ; police and policing, 5 , 100 , 114 – 16 , 122 , wharves 144 , 171 grain, l our, or bread procurement and Severan reorganization of, 96 – 98 distribution, 27 , 89 , 96 – 100 , staf and minor oi cials, 48 , 91 , 116 , 126 , 175 , 215 102 , 115 , 117 , 124 , 166 , 171 , 177 , zones and zoning, 6 , 38 , 84 , 85 , 126 , 127 182 , 184 – 85 administration, medieval frumentationes , 46 , 97 charitable institutions, 158 , 169 , 179 – 87 , 191 , headquarters of administrative oi ces, 81 , 85 , 201 , 299 114 – 17 , 214 Church. -

Reading Death in Ancient Rome

Reading Death in Ancient Rome Reading Death in Ancient Rome Mario Erasmo The Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Erasmo, Mario. Reading death in ancient Rome / Mario Erasmo. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1092-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1092-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Death in literature. 2. Funeral rites and ceremonies—Rome. 3. Mourning cus- toms—Rome. 4. Latin literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PA6029.D43E73 2008 870.9'3548—dc22 2008002873 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1092-5) CD-ROM (978-0-8142-9172-6) Cover design by DesignSmith Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI 39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents List of Figures vii Preface and Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION Reading Death CHAPTER 1 Playing Dead CHAPTER 2 Staging Death CHAPTER 3 Disposing the Dead 5 CHAPTER 4 Disposing the Dead? CHAPTER 5 Animating the Dead 5 CONCLUSION 205 Notes 29 Works Cited 24 Index 25 List of Figures 1. Funerary altar of Cornelia Glyce. Vatican Museums. Rome. 2. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus. Vatican Museums. Rome. 7 3. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus (background). Vatican Museums. Rome. 68 4. Epitaph of Rufus. -

Lays of Ancient Rome by Thomas Babington Macaulay

% nvy tkvr /S^lU, CsUdx *TV IrrTCV* U- tv/ <n\V ftjw ^ Jl— i$fO-$[ . To live ^ Iz^l.cL' dcn^LU *~d |V^ ^ <X ^ ’ tri^ v^X H c /f/- v »»<,<, 4r . N^P’iTH^JJs y*^ ** 'Hvx ^ / v^r COLLECTION OF BRITISH AUTHORS. VOL. CXCVIII. LAYS OF ANCIENT ROME BY THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULAY. IN ONE VOLUME. TATJCHNITZ EDITION". By the same Author, THE HISTORY OF ENGLAND.10 vols. CRITICAL AND HISTORICAL ESSAYS.5 vols. SPEECHES .2 vols. BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS.1 vol. WILLIAM PITT, ATTERBURY.1 VOl. THE LIFE AND LETTERS OF LORD MACAULAY. By his Nephew GEORGE OTTO TREVELYAN, M.P.4 vols. SELECTIONS FROM THE WRITINGS OF LORD MACAULAY. Edited by GEORGE OTTO TREVELYAN, M.P. * . 2 vols. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/laysofancientrom00maca_3 LAYS OF ANCIENT ROME: WITH IVEY” AND “THE AEMADA” THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULAY. COPYRIGHT EDITION, LEIPZIG BERNHARD TAUCIINITZ 1851. CONTENTS. Page PREFACE . i HORATIUS.35 THE BATTLE OF THE LAKE REGILLUS.81 VIRGINIA.143 THE PROPHECY OF CAPYS.189 IVRY: A SONG OF THE HUGUENOTS ..... 221 THE ARMADA: A FRAGMENT.231 4 PREFACE. That what is called the history of the Kings and early Consuls of Rome is to a great extent fabulous, few scholars have, since the time of Beaufort, ven¬ tured to deny. It is certain that, more than three hundred and sixty years after the date ordinarily assigned for the foundation of the city, the public records were, with scarcely an exception, destroyed by the Gauls. It is certain that the oldest annals of the commonwealth were compiled more than a cen¬ tury and a half after this destruction of the records. -

Our Young Folks' Plutarch

Conditions and Terms of Use PREFACE Copyright © Heritage History 2009 The lives which we here present in a condensed, simple Some rights reserved form are prepared from those of Plutarch, of whom it will perhaps be interesting to young readers to have a short account. Plutarch This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an organization was born in Chæronea, a town of Bœotia, about the middle of the dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history books, and to the promotion first century. He belonged to a good family, and was brought up of the works of traditional history authors. with every encouragement to study, literary pursuits, and virtuous The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public domain and actions. When very young he visited Rome, as did all the are no longer protected by the original copyright. They may therefore be reproduced intelligent Greeks of his day, and it is supposed that while there he within the United States without paying a royalty to the author. gave public lectures in philosophy and eloquence. He was a great admirer of Plato, and, like that philosopher, believed in the The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, however, are the property of Heritage History and are licensed to individual users with some immortality of the soul. This doctrine he preached to his hearers, restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the integrity and taught them many valuable truths about justice and morality, of the work itself, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure that of which they had previously been ignorant. -

Framing the Sun: the Arch of Constantine and the Roman Cityscape Elizabeth Marlowe

Framing the Sun: The Arch of Constantine and the Roman Cityscape Elizabeth Marlowe To illustrate sonif oi the key paradigm shifts of their disci- C^onstantine by considering the ways its topographical setting pline, art historians often point to the fluctuating fortunes of articulates a relation between the emperor's military \ictoiy ihe Arrh of Constantine. Reviled by Raphael, revered by Alois and the favor of the sun god.'' Riegl, condemned anew by the reactionary Bernard Beren- son and conscripted by the openly Marxist Ranucchio Bian- The Position of the Arch rhi Bandineili, the arch has .sened many agendas.' Despite In Rome, triumphal arches usually straddled the (relatively their widely divergent conclusions, however, these scholars all fixed) route of the triumphal procession.^ Constantine's share a focus on the internal logic of the arcb's decorative Arch, built between 312 and 315 to celebrate his victory over program. Time and again, the naturalism of the monument's the Rome-based usuiper Maxentius (r. 306-12) in a bloody spoliated, second-century reliefs is compared to the less or- civil war, occupied prime real estate, for the options along ganic, hieratic style f)f the fourth-<:entur\'canings. Out of that the "Via Triumphalis" (a modern term but a handy one) must contrast, sweeping theorie.s of regrettable, passive decline or have been rather limited by Constantine's day. The monu- meaningful, active transformation are constructed. This ment was built at the end of one of the longest, straightest methodology' has persisted at the expense of any analysis of stretches along the route, running from the southern end of the structure in its urban context. -

Rome Before Rome: the Role of Landscape Elements, DOI: 10.13128/Rv-7020 - Distributed Undertheterms Ofthecc-BY-4.0 Licence Press

Rome before Rome: the role of landscape elements, together with technological approaches, shaping the foundation of the Roman civilization ri-vista Federico Cinquepalmi Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA) Italian National Institute for Environmental Protection and Research [email protected] 01 2019 Abstract Most of the ancient cities link their initial fortune to the uniqueness of their geographical po- sition: rivers, hills, islands and natural resources are playing a fundamental role in the game of seconda serie shaping a powerful future for any urban settlement. However, very few cities share the astonish- ing destiny of the City of Rome, where all those factors, together with the powerful boost of its citizen’s determination and their primitive but effective technologies, have contributed to design the fate of that urban area, establishing the basis of western civilization and giving a fundamen- tal contribution of all humankind. Keywords Archaic smart cities, knowledge management, strategic management, paleo-urban technol- ogies, ancient building environment, urban civilization, landscape analysis, urban history, geo- graphical analysis. Received: July 2019 / Accepted: August 2019 | © 2019 Author(s). Open Access issue/article(s) edited by QULSO, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-4.0 and published by Firenze University Press. Licence for metadata: CC0 1.0 168 DOI: 10.13128/rv-7020 - www.fupress.net/index.php/ri-vista/ Cinquepalmi Introduction Etruscans held a strong flow of commerce both by After starting from small and humble beginnings, land and sea, especially on pottery and metallic ar- has grown to such dimensions that it begins to be tifacts like jewels and blades1. -

The Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia By

Legendary Art & Memory in Republican and Imperial Rome: the Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia By Copyright 2014 Andrea Samz-Pustol Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Phil Stinson ________________________________ John Younger ________________________________ Tara Welch Date Defended: June 7, 2014 The Thesis Committee for Andrea Samz-Pustol certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Legendary Art & Memory in Republican and Imperial Rome: the Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia ________________________________ Chairperson Phil Stinson Date approved: June 8, 2014 ii Abstract The display contexts of the bronze statues of legendary heroes, Horatius Cocles and Cloelia, in the Roman Forum influenced the representation of these heroes in ancient texts. Their statues and stories were referenced by nearly thirty authors, from the second century BCE to the early fifth century CE. Previous scholarship has focused on the bravery and exemplarity of these heroes, yet a thorough examination of their monuments and their influence has never been conducted.1 This study offers a fresh outlook on the role the statues played in the memory of ancient authors. Horatius Cocles and Cloelia are paired in several ancient texts, but the reason for the pairing is unclear in the texts. This pairing is particularly unique because it neglects Mucius Scaevola, whose deeds were often relayed in conjunction with Horatius Cocles’ and Cloelia’s; all three fought the same enemy at the same time and place. This pairing can be attributed, however, to the authors’ memory of the statues of the two heroes in the Forum. -

![Atlas of Ancient Rome [PDF] Sampler](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4455/atlas-of-ancient-rome-pdf-sampler-4514455.webp)

Atlas of Ancient Rome [PDF] Sampler

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical ill. 4 Forum Nervae, aedes Minervae . Reconstruction by Meneghini, Santangeli Valenzani 2007, Inklink illustration.means without prior written permission of the publisher. Forum of Nerva Foro Nerva Imperiale © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. ill. 22 The Forum Boarium in the late imperial period, as seen from Tiberina Island. In the foreground is the portus Tiberinus and pons Aemilius. Left to right: ianus quadrifrons, fornix Augusti, aedes Portuni, aedes Aemiliana Herculis, aedes Herculis Victoris, and the consaeptum sacellum. In the background, from left to right, are the horrea at the food of the Cernalus, insula, titulus Anastasiae on the maenianum of the domus Augusti and Circus Maximus. Reconstruction by C. Bariviera, illustration by Inklink. Forum Boarium Foro Boario © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Palazzo Domiziano Domitian’s Palace ill. 13 Palatium, domus Augustiana, AD 117-138. From right to left: in contact with the Augustan constructions—arcus C. Octavii, domus private Augusti, aedes Appolinis and in front of the portico—were imperial palaces; domus Tiberiana, with a substructed base used for a garden (bottom right), and domus Augustiana, facing the area Palatina (bottom left). The public buildings, surrounded by a portico on two sides, included two large receiving halls, with the so-called aula Regia in the center, sumptuous architectural decoration and a roof in imitation of a temple, and the apsed basilica to the right; these were followed by an octagonal peristyle and the so-called triclinium or cenatio Jovis. -

Masons, Materials, and Machinery: Logistical Challenges in Roman

Masons, Materials, and Machinery: Logistical Challenges in Roman Building Brian Sahotsky The Augustan-era poet Tibullus records an episode in the life of a Republican merchant, “His fancy turns to foreign marbles, and through the trembling city his column is carried by one thousand sturdy pairs of oxen.”1 By sheathing Rome in marble during the early 1st c. A.D. Augustus essentially prefigured three centuries of colossal stone construction in the capital.2 Subsequent emperors favored massive monolithic columns, metaphorically equating their size and distinctiveness with the might and reach of the empire. These exotic marbles, pried from quarries in peripheral locales like Egypt and Anatolia, demonstrated that Rome could bring wealth from any of its territories to showcase in the capital. Although these marble monoliths were a symbol for the supremacy of Rome, the real power was displayed in their erection.3 Key imperial construction projects developed into major spectacles, and the convoy of marble columns and cartloads of building materials to the building site shook the ground and commanded attention. One such case study from the Tetrarchic period is the building of the great Basilica of Maxentius at the southern end of the Roman Forum.4 In addition to its vast quantity of brick and concrete, the plans for the basilica specified eight Proconnesian marble columns that weighed in excess of 90 tons. These columns contained the perfect means to put on a dramatic show of Roman engineering and organizational expertise. The resulting parade of stone and brick to the Forum glorified the ambitious building program of the Emperor, and gave the people of Rome a spectacle that had been absent in the capital for nearly a hundred years.5 1 Tibullus, Elegiae, 2.3.43-44. -

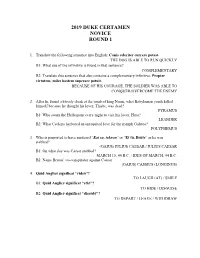

Duke Certamen Novice Questions 2019

2019 DUKE CERTAMEN NOVICE ROUND 1 1. Translate the following sentence into English: Canis celeriter currere potest. THE DOG IS ABLE TO RUN QUICKLY B1: What use of the infinitive is found in that sentence? COMPLEMENTARY B2: Translate this sentence that also contains a complementary infinitive: Propter virtutem, miles hostem superare potuit. BECAUSE OF HIS COURAGE, THE SOLDIER WAS ABLE TO CONQUER/OVERCOME THE ENEMY 2. After he found a bloody cloak at the tomb of king Ninus, what Babylonian youth killed himself because he thought his lover, Thisbe, was dead? PYRAMUS B1: Who swam the Hellespont every night to visit his lover, Hero? LEANDER B2: What Cyclops harbored an unrequited love for the nymph Galatea? POLYPHEMUS 3. Who is purported to have muttered “Kai su, teknon” or “Et tu, Brute” as he was stabbed? (GAIUS) IULIUS CAESAR / JULIUS CAESAR B1: On what day was Caesar stabbed? MARCH 15, 44 B.C. / IDES OF MARCH, 44 B.C. B2: Name Brutus’ co-conspirator against Caesar. (GAIUS) CASSIUS (LONGINUS) 4. Quid Anglicē significat “rīdeō”? TO LAUGH (AT) / SMILE B1: Quid Anglicē significat “cēlō”? TO HIDE / DISGUISE B2: Quid Anglicē significat “discēdō”? TO DEPART / LEAVE / WITHDRAW 5. What ship carried heroes like Castor, Pollux, Orpheus and Jason on their quest to retrieve the golden fleece? THE ARGO B1: What woman volunteered to join the crew but was denied by Jason because he thought having a woman aboard would cause dissension? ATALANTA B2: What wily king of Iolcus, the uncle of Jason, had tricked him into promising to retrieve the golden fleece? PELIAS SCORE CHECK 6. -

Space, Ritual, Event: Constantine's Jubilee of 326 and Its Implications on Urban Space

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2013 Space, Ritual, Event: Constantine's Jubilee of 326 and its Implications On Urban Space Brian Christopher Doherty [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Doherty, Brian Christopher, "Space, Ritual, Event: Constantine's Jubilee of 326 and its Implications On Urban Space. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2409 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Brian Christopher Doherty entitled "Space, Ritual, Event: Constantine's Jubilee of 326 and its Implications On Urban Space." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Architecture, with a major in Architecture. Gregor A. Kalas, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Avigail Sachs, Thomas K. Davis Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Space, Ritual, Event: Constantine's Jubilee of 326 and its Implications On Urban Space A Thesis presented for the the Master of Architecture Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Brian Christopher Doherty August 2013 ABSTRACT Architecture has been characterized as the study of space. -

Figure 1 Plan of the Area of the Forum Romanum and the Imperial Fora in Antiquity. the Five Imperial Fora Are to the North; To

Figure 1 Plan of the area of the Forum Romanum and the Imperial Fora in antiquity. The five Imperial Fora are to the north; to the south, the irregular piazza of the Forum Romanum lies between the Basilica Julia and the Basilica Aemilia (drawing by Joseph Skinner, adapted). Memory and Movement in the Roman Fora from Antiquity to Metro C amy russell Durham University Introduction: Movement and Memory movement can illuminate the enduring influence of ancient street networks on the modern cityscape. The Forum he built landscape of the city of Rome is a powerful Romanum and the neighboring Imperial Fora shared in engine of cultural memory.1 The visitor can pick antiquity and still share today a similar role as places of out elements of buildings two thousand years old T memory, but they have had different relationships to urban woven into the fabric of the modern city at every street corner movement networks (Figure 1). The Forum Romanum’s in the centro storico.2 But there is more to Rome than picture- function as a node on several ancient, medieval, and Renais- postcard images of crumbling columns juxtaposed with mod- sance major routes was vital to its preservation as a place of ern development. In Rome, perhaps more than anywhere memory for centuries until it was isolated and enclosed in else, ancient architecture is experienced not only as isolated the twentieth century. The Imperial Fora, on the other hand, and picturesque ruins but also as an integral part of the living became isolated from movement networks, and their histori- city.