Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Booklet Pages

A Gallery Dedicated to the Illumination of God’s Plan of Salvation As Depicted In Classical Art © Copyright St. Francis of Assisi Parish, Colorado Springs, CO. 2016 THE ART OF SALVATION PROJECT GOALS: v Introduce sacred art as a part of our Catholic heritage v Model the typological reading of Scripture, as taught by the Church v Illuminate God’s divine Plan of Salvation through sacred art As Catholics, we have a rich heritage of the illumination of the Word of God through great art. During most of history, when the majority of people were illiterate, the Church handed on the Deposit of Faith not only in reading and explaining the written Word in her liturgies, but also in preaching the Gospel through paintings, sculptures, mosaics, drama, architecture, and stained glass. In “The Art of Salvation” project, we hope to reclaim that heritage by offering a typological understanding of the plan of salvation through classical art. What is Divine Typology? “Typology is the study of persons, places, events and institutions in the Bible that foreshadow later and greater realities made known by God in history. The basis for such study is the belief that God, who providentially shapes and determines the course of human events, infuses those events with a prophetic and theological significance” (Dr. Scott Hahn, Catholic Bible Dictionary) “The Church, as early as apostolic times, and then constantly in her Tradition, has illuminated the unity of the divine plan in the two Testaments through typology, which discerns in God’s works of the Old Covenant prefigurations of what he accomplished in the fullness of time in the person of his incarnate Son” (CCC 128). -

Pestilence and Prayer: Saints and the Art of The

PESTILENCE AND PRAYER: SAINTS AND THE ART OF THE PLAGUE IN ITALY FROM 1370 - 1600 by JESSICA MARIE ORTEGA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Art History in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 Thesis Chair: Dr. Margaret Zaho ABSTRACT Stemming from a lack of scholarship on minor plague saints, this study focuses on the saints that were invoked against the plague but did not receive the honorary title of plague patron. Patron saints are believed to transcend geographic limitations and are charged as the sole reliever of a human aliment or worry. Modern scholarship focuses on St. Sebastian and St. Roch, the two universal plague saints, but neglects other important saints invoked during the late Medieval and early Renaissance periods. After analyzing the reasons why St. Sebastian and St. Roch became the primary plague saints I noticed that other “minor” saints fell directly in line with the particular plague associations of either Sebastian or Roch. I categorized these saints as “second-tier” saints. This categorization, however, did not cover all the saints that periodically reoccurred in plague-themed artwork, I grouped them into one more category: the “third-tier” plague saints. This tier encompasses the saints that were invoked against the plague but do not have a direct association to the arrow and healing patterns seen in Sts. Sebastian and Roch iconographies. This thesis is highly interdisciplinary; literature, art, and history accounts were all used to determine plague saint status and grouping, but art was my foundation. -

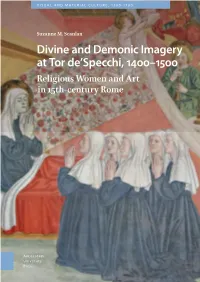

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Florence Next Time Contents & Introduction

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Conventional names for traditional religious subjects in Renaissance art The Cathedral of Florence (Duomo) The Baptistery Museo dell’Opera del Duomo The other Basilicas of Florence Introduction Santissima Annunciata Santa Croce and Museum San Lorenzo and Medici Chapels San Marco and Museum Santa Maria del Carmine and Brancacci Chapel Santa Maria Novella and Museum San Miniato al Monte Santo Spirito and Museum Santa Trinita Florence’s other churches Ognissanti Orsanmichele and Museum Santi Apostoli Sant’Ambrogio San Frediano in Cestello San Felice in Piazza San Filippo Neri San Remigio Last Suppers Sant’Apollonia Ognissanti Foligno San Salvi San Marco Santa Croce Santa Maria Novella and Santo Spirito Tours of Major Galleries Tour One – Uffizi Tour Two – Bargello Tour Three – Accademia Tour Four – Palatine Gallery Museum Tours Palazzo Vecchio Museo Stefano Bardini Museo Bandini at Fiesole Other Museums - Pitti, La Specola, Horne, Galileo Ten Lesser-known Treasures Chiostro dello Scalzo Santa Maria Maggiore – the Coppovaldo Loggia del Bigallo San Michele Visdomini – Pontormo’s Madonna with Child and Saints The Chimera of Arezzo Perugino’s Crucifixion at Santa Maria dei Pazzi The Badia Fiorentina and Chiostro degli Aranci The Madonna of the Stairs and Battle of the Centaurs by Michelangelo The Cappella dei Magi, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi The Capponi Chapel at Santa Felicita Biographies of the Artists Glossary of Terms Bibliography SimplifiedTime-line diagram Index INTRODUCTION There can’t be many people who love art who won’t at some time in their lives find themselves in Florence, expecting to see and appreciate the incredibly beautiful paintings and sculptures collected in that little city. -

Visual Exegesis and Eschatology in the Sistine Chapel

TYPOLOGY AT ITS LIMITS: VISUAL EXEGESIS AND ESCHATOLOGY IN THE SISTINE CHAPEL Giovanni Careri Typology is a central device in the Sistine chapel frescoes of the fifteenth century where it works, in a quite canonical way, as a model of histori- cal temporality with strong institutional effects. In the frescoes by Luca Signorelli and Bartolomeo della Gatta representing various episodes from the life of Moses, including his death, every gesture and action of Moses is an announcement – a figura – of Jesus Christ’s institutional accomplish- ments represented on the opposite wall [Fig. 1]. Some of these devices operate on a figural level rather than in mere iconographical terms; the death of Moses, for instance, is a Pathosformel: the leader of the Israelites dies in the pose of the dead body of Christ, while his attendants adum- brate the Lamentation of Christ. Here, the attitude of the defunct Moses is ‘intensified’ by the return of the pathetic formula embodied by Christ’s Fig. 1. Luca Signorelli and Bartolomeo della Gatta, Last Acts and Death of Moses (1480–1482). Oil on panel, 21.6 × 48 cm. Vatican City, Sistine Chapel. 74 giovanni careri corpse, that is, by the paradoxical return of the figure who is prefigured by Moses himself. As Leopold Ettlinger extensively showed, the main ideological purpose of the Quattrocento cycle is to support and incontrovertibly to adduce papal primacy.1 Nevertheless, if we look at these frescoes from an anthro- pological point of view, we are compelled to observe the extent to which they appropriate the history of the ‘Other’ – in this case the history of the Jews – entirely transforming it into a sort of prophetical premise for Christian history itself. -

Fall 2019 Newsletter

Fall 2019 Newsletter Dear Friends of Florence, Welcome to autumn as we look ahead to the charms and delights of the fall/winter season. Since our spring newsletter, we have more updates to share with you. It is your generous support that enables us to keep our wonderful team of conservators busy, as you will see below, as they work to restore and revivify Renaissance masterpieces. We have more projects completed, in process, and on the horizon in Florence and beyond—including examples on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration in New York City this fall. A s a tribute to our work together over twenty-one years, Simonetta Brandolini d’Adda —our dynamic co-founder and president—was deeply honored to receive the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (Cavaliere Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana)— the Italian equivalent of a knighthood. Again, this was a direct result of your generosity as we celebrate our accomplishments to date and look to the future together! NEWS Friends of Florence’s spring program, “The Mature Michelangelo: Artist and Architect,” took place May 31‒June 6, 2019, in Florence and Rome. Our wonderful group was led by the brilliant art historians William Wallace, the Barbara Murphy Bryant Distinguished Professor of Art History at Washington University in St. Louis, and Ross King who enthusiastically shared their deep knowledge of the artist, his life and times, and his legacy. With a marvelous itinerary they developed with Simonetta and the diligent Friends of Florence team, the group enjoyed an exploration of Michelangelo’s years as an established artist, designer, and architect. -

Download PDF Datastream

DOORWAYS TO THE DEMONIC AND DIVINE: VISIONS OF SANTA FRANCESCA ROMANA AND THE FRESCOES OF TOR DE’SPECCHI BY SUZANNE M. SCANLAN B.A., STONEHILL COLLEGE, 2002 M.A., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2006 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART AND ARCHITECTURE AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY, 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Suzanne M. Scanlan ii This dissertation by Suzanne M. Scanlan is accepted in its present form by the Department of History of Art and Architecture as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date_____________ ______________________________________ Evelyn Lincoln, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date______________ ______________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Reader Date______________ ______________________________________ Caroline Castiglione, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date______________ _____________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii VITA Suzanne Scanlan was born in 1961 in Boston, Massachusetts and moved to North Kingstown, Rhode Island in 1999. She attended Stonehill College, in North Easton, Massachusetts, where she received her B.A. in humanities, magna cum laude, in 2002. Suzanne entered the graduate program in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Brown University in 2004, studying under Professor Evelyn Lincoln. She received her M.A. in art history in 2006. The title of her masters’ thesis was Images of Salvation and Reform in Poccetti’s Innocenti Fresco. In the spring of 2006, Suzanne received the Kermit Champa Memorial Fund pre- dissertation research grant in art history at Brown. This grant, along with a research assistantship in Italian studies with Professor Caroline Castiglione, enabled Suzanne to travel to Italy to begin work on her thesis. -

Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy: Ritual, Spectacle, Image Edited by Barbara Wisch and Diane Cole Ahl Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-40340-6 - Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy: Ritual, Spectacle, Image Edited by Barbara Wisch and Diane Cole Ahl Frontmatter More information Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy: Ritual, Spectacle, Image is the first book to consider the role of Italian confraternities in the patronage of art. Eleven interdisciplinary essays analyze confraternal painting, sculpture, architec ture, and dramatic spectacles by documenting the unique historical and ritual con texts in which they were experienced. Exploring the evolution of devotional prac tices, the roles of women and youths, the age's conception of charity, and the importance of confraternities in civic politics and urban design, this book offers new approaches to one of the most dynamic forms of corporate patronage in early modern Italy. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-40340-6 - Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy: Ritual, Spectacle, Image Edited by Barbara Wisch and Diane Cole Ahl Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-40340-6 - Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy: Ritual, Spectacle, Image Edited by Barbara Wisch and Diane Cole Ahl Frontmatter More information Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy Ritual, Spectacle, Image Edited -

Rome Festive Welcome Dinner with Drinks and Music!

FRA NOI’S TREASURE HUNT OF ROME AND FLORENCE October 16-25, 2015 OCTOBER 16 (depart from US) OCTOBER 17 – ROME FESTIVE WELCOME DINNER WITH DRINKS AND MUSIC! OCTOBER 18 – ROME Morning: Our adventure starts at the foot of the Capitoline Hill, the site of major temples in ancient Roman times. From the back of the Capitoline we have a great overview of the Roman Forum, the political heart of ancient Rome. Then it’s on to the Colosseum, where our reserved tickets allow us to bypass lines. Afternoon: We begin our afternoon at the Pantheon, the best preserved of all imperial Roman buildings. From there, we walk to the Trevi Fountain, and on our way back we can stop to admire the spectacular ceiling paintings in the churches of San’t Ignazio and Il Gesù. OCTOBER 19 - ROME Morning: The bus leaves us near the entrance to the piazza in front of St. Peter’s Basilica. We walk across the piazza, enter the world’s largest church, and take a turn around the enormous interior, viewing Michelangelo’s Pietà and the two great Bernini altars: the Baldachino and the Chair of Peter. From there we walk past Castel Sant’ Angelo, originally the tomb of the emperor Hadrian, and across the Ponte Sant’ Angelo, lined with Bernini statues nicknamed “Bernini’s Breezy Maniacs,” due to their wind-blown appearance. Afternoon: We explore the Catacombs of Priscilla, among the oldest of Rome’s underground cemeteries used by the city’s early Christians. OCTOBER 20 – ROME/SORRENTO Morning: We start our day at Villa Borghese. -

Art As Power: the Medici Family As Magi in The

ART AS POWER The Medici Family as Magi in the Fifteenth Century The Medici family of the Italian Renaissance were portrayed in works by Benozzo Gozzoli and Sandro Botticelli as Magi, the venerated figures from the new testament who were the first gentiles to recognize Jesus’ divinity. In doing so, the family transformed their desire for power into the physical realm and blurred the boundary between politics and religion. By Janna Adelstein Vanderbilt University n the middle of fifteenth-century Florence, the Medici it the Virgin Mary after the birth of her son, Jesus Christ. were at the height of their power and influence. Lead Often, the Medici would commission the artist to present by the great Cosimo, this family of bankers resided in various family members as the Magi themselves, melding Ithe heart of the city. Their unparalleled financial and soci- religious history and their contemporary world. This bib- etal status was measured in part by a consistent devotion to lical trio was held in high esteem by the family due to the the arts. This patronage is appraised through the Medicis’ family’s involvement in the confraternity the Compagnia close relationships with their favorite artists, such as Ben- de’ Magi, which was dedicated to the group. I will argue in ozzo Gozzoli and Sandro Botticelli, who often lived in the this paper that through an analysis of paintings in which Palazzo de Medici and enjoyed personal relationships with the family is depicted as these biblical figures and the Medi- members of the family. As was customary for art of the time, cis’ involvement in the Compagnia de’ Magi, we can begin many of the works commissioned by the family featured the to uncover why Cosimo desired to align himself with the biblical trio of the Magi, who were the first people to vis- Magi, and the political consequences of such a parallel. -

Benozzo Gozzoli, Florentine School

THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/benozzogozzoliflOOunse : MASTERS IN ART BRAUN’S ^m^jffllu9tratEd-iIipnojarapl)3 CARBON PRINTS Among the artists to be considered during the current, 1905, Volume may be mentioned Fra Filippo Lippi, Sir Henry Rae- burn, Claude Lorrain, Memlinc, and Verrocchio. The num- FINEST AND MOST DURABLE 1 bers of 4 Masters in Art which have already appeared in 1905 are IMPORTED WORKS OF ART Part 61, JANUARY WATTS Part 62, FEBRUARY . PALMA VECCHIO Part 63, MARCH MADAME VIGEE LE BRUN NE HUNDRED THOUSAND direct Part 64, APRIL MANTEGNA Part 65, MAY . CHARDIN ^^reproductions from the original paintings Part 66, JUNE . BENOZZO GOZZOLI and drawings by old and modern masters in the PART 67 , THE ISSUE FOR galleries of Amsterdam, Antwerp, Berlin, Dres- fuly den, Florence, Haarlem, Hague, London, Ma- WILL TREAT OF drid, Milan, Paris, St. Petersburg, Rome, g>tcrn Venice, Vienna, Windsor, and others. 3lan Special Terms to Schools. NUMBERS ISSUED IN PREVIOUS VOLUMES OF ‘MASTERS IN ART’ BRAUN, CLEMENT & CO. VOL. 1. VOL. 2. 249 Fifth Avenue, corner 28th Street Part 1 —VAN DYCK Part 13. —RUBENS Part 2 —TITIAN Part 14- —DA VINCI NEW YORK CITY Part 3 — VELASQUEZ Part I 5- — DURER Part 4 — HOLBEIN Part 16. — MICHELANGELO* Part 5 — BOTTICELLI Part 17. — MI CHELANGELOf Part 6 —REMBRANDT Part 18. —COROT Part 7 —REYNOLDS Part 19- —BURNE-JONES Part 8 — MILLET Part 20. —TER BORCH Part 9 — GIO. BELLINI Part 21. —DELLA ROBBIA Part 10 —MURILLO Part 22. —DEL SARTO Part 11 —HALS Part 21- —GAINSBOROUGH Part 12 —RAPHAEL Part 24. -

Roma 1430-1460. Pittura Romana Prima Di Antoniazzo

Roma 1430-1460. Pittura romana prima di Antoniazzo stefano PETROCCHI Le fonti storiche e biografiche pontificali delineano concor- Presenze marchigiane a Roma demente l’evento giubilare della metà del secolo come un nella prima metà del Quattrocento momento culminante di energie e progetti che sancisce la La più grande impresa della prima metà del secolo, le Storie conclusione della storia medievale della città e per conse- di san Giovanni Battista, realizzata a partire dal 1427 da Gen- guenza l’avvento della Roma moderna. tile da Fabriano nella cattedrale del Laterano, recuperava la Trascorsi trent’anni dal trionfale ritorno di un potere papale tradizione figurativa delle basiliche maggiori. Modello di rife- autorevole e rinnovatore, con la leggendaria entrata in cit- rimento dell’impianto decorativo, diviso in registri con figu- tà di Martino V Colonna (28 settembre 1420), e nonostante re monumentali e riquadri narrativi, era la primitiva navata l’incerto pontificato di Eugenio IV (1431-1447), trascorso per paleocristiana di San Pietro, ancora in opera in quegli anni, nove anni a Firenze, l’elezione di Niccolò V nel 1447 era cari- ribadito da Pietro Cavallini alla fine del Duecento sia in quella ca di attese inedite nella storia secolare di Roma1. ostiense sia nell’altra trasteverina di Santa Cecilia negli anni Segno inequivocabile di una volontà di rifondazione e di del primo giubileo2. Con la riaffermazione dell’antico prototi- una nuova vocazione universalistica della Chiesa era il tra- po, si ricomprendeva simbolicamente anche il disegno politico sferimento della residenza pontificia dalla sua sede storica e e morale di quell’evento. millenaria del Laterano – che aveva tramandato la continuità La presenza a Roma della maggiore produzione di Gentile da imperiale romana – alla cittadella vaticana riunita intorno Fabriano, per estensione e importanza storica, dovette inci- alla basilica di San Pietro, con il mandato di condurre la nuo- dere profondamente sulla pittura locale fermamente ancora- va prospettiva ecumenica aperta dal concilio di Firenze.