Race and Representation in Disney's Live-Action Remakes of Aladdin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racism and Stereotypes: Th Movies-A Special Reference to And

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific ResearchResearch Larbi Ben M’h idi University-Oum El Bouaghi Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Racism and Stereotypes: The Image of the Other in Disney’s Movies-A Special Reference to Aladdin , Dumbo and The Lion King A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D egree of Master of Arts in Anglo-American Studies By: Abed Khaoula Board of Examiners Supervisor: Hafsa Naima Examiner: Stiti Rinad 2015-2016 Dedication To the best parents on earth Ouiza and Mourad To the most adorable sisters Shayma, Imène, Kenza and Abir To my best friend Doudou with love i Acknowledgements First of all,I would like to thank ‘A llah’ who guides and gives me the courage and Patience for conducting this research.. I would like to express my deep appreciation to my supervisor Miss Hafsa Naima who traced the path for this dissertation. This work would have never existed without her guidance and help. Special thanks to my examiner Miss Stiti Rinad who accepted to evaluate my work. In a more personal vein I would like to thank my mother thousand and one thanks for her patience and unconditional support that facilitated the completion of my graduate work. Last but not least, I acknowledge the help of my generous teacher Mr. Bouri who believed in me and lifted up my spirits. Thank you for everyone who believed in me. ii ا ا أن اوات ا اد ر ر دة اطل , د ه اوات ا . -

About Disney's Newsies Character Breakdown

About Disney’s Newsies Based on the real-life Newsboy Strike of 1899, this new Disney musical tells the story of Jack Kelly, a rebellious newsboy who dreams of a life as an artist away from the big city. After publishing giant Joseph Pulitzer raises newspaper prices at the newsboys’ expense, Jack and his fellow newsies take action. With help from the intrepid reporter Katherine Plumber, all of New York City soon recognizes the power of young people. From the award winning minds of Alan Menken (Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin) and four-time Tony® Award winner Harvey Fierstein (La Cage aux Folles, Kinky Boots), you’ll be singing along to the hit songs “King of New York”, “Seize the Day,” and “Santa Fe.” Character Breakdown: JACK KELLY – leader of the newsies CRUTCHIE – newsie with a bum leg DAVEY – new, bookish newsie LES – Davey’s fearless younger brother. (ELEMENTARY AGE) RACE, ALBERT, SPECS, HENRY, FINCH, ROMEO, ELMER MUSH, BUTTONS, TOMMY BOY, JOJO, SPLASHER, MIKE, IKE – newsies SCABS (3) SPOT CONLON – Leader of the Brooklyn Newsies KATHERINE PLUMBER – feisty/ambitious young reporter DARCY – upper-class son of a publisher BILL – son of William Randolf Hearst WIESEL – runs the distribution window of The World MORRIS DELANCEY– heavy at The World’s distribution window OSCAR DELANCEY – Morris’s equally tough brother JOSEPH PULITZER – no-nonsense Publisher of The World SEITZ – Pulitzer’s editor BUNSEN – Pulitzer’s bookkeeper HANNAH – Pulitzer’s secretary NUNZIO – Pulitzer’s barber GUARD SNYDER – warden of The Refuge; a frightening and sinister man MEDDA LARKIN – A vaudeville star, owns her own theater BOWERY BEAUTIES – showgirls at Medda’s theatre STAGE MANAGER NUNS (3) WOMAN – newspaper customer JACOBI – owner of Jacobi’s deli POLICEMEN MAYOR GOVENOR TEDDY ROOSEVELT . -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

“A Whole New World” by Zayn Malik and Zhavia Ward

PROJECT (Professional Journal of English Education) p–ISSN 2614-6320 Volume 3, No. 4, July 2020 e–ISSN 2614-6258 AN ANALYSIS OF FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE USED IN THE LYRIC OF “A WHOLE NEW WORLD” BY ZAYN MALIK AND ZHAVIA WARD Siti Nursolihat 1, Evie Kareviati2 1 IKIP Siliwangi 2 IKIP Siliwangi 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected] Abstract Language is a tool of communication used by people anywhere and every time. Now days people commonly find a figurative language in daily life, for example in a lyric of song. Figurative language is a way to express an idea in implicit way. This research is trying to analyze the figurative languages which exist in the lyric of song “A Whole New World” and trying to find out its meaning by analyzing its contextual meaning. This is a descriptive qualitative research. The data instrument is the song lyric which taken from Genius website. The result showed that this song consist of some figurative languages, such as alliteration, simile, personification, metaphor, and hyperbole. Furthermore, the most figurative language used in the lyric is metaphor. It is highly relatable with the imaginative theme of the song itself. The contextual meaning of each figurative language is also explained based on the situation of the lyric. Keywords: Figurative Language, Song Lyric, Contextual Meaning INTRODUCTION Language is a tool of communication used by the people, orally or writing. Basic aim of language learning nowdays is communication and vocabulary plays an important role in conversation (Komorowska, 2005) as cited in Nurdiansyah, Asyid, & Parmawati (2019). -

Bono, the Culture Wars, and a Profane Decision: the FCC's Reversal of Course on Indecency Determinations and Its New Path on Profanity

Bono, the Culture Wars, and a Profane Decision: The FCC's Reversal of Course on Indecency Determinations and Its New Path on Profanity Clay Calvert* INTRODUCTION The United States Supreme Court has rendered numerous high- profile opinions in the past thirty-five years regarding variations of the word "fuck." Paul Robert Cohen's anti-draft jacket,' Gregory Hess's threatening promise, 23George Carlin's satirical monologue,3 and Barbara Susan Papish's newspaper headline 4 quickly come to mind. 5 These now-aging opinions address important First Amendment issues of free speech, such as protection of political dissent,6 that continue to carry importance today. It is, however, a March 2004 ruling * Associate Professor of Communications & Law and Co-director of the Pennsylvania Center for the First Amendment at The Pennsylvania State University. B.A., 1987, Communication, Stanford University; J.D. with Great Distinction and Order of the Coif, 1991, McGeorge School of Law, University of the Pacific; Ph.D., 1996, Communication, Stanford University. Member, State Bar of California. 1. Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971) (protecting, as freedom of expression, the right to wear ajacket emblazoned with the words "Fuck the Draft" in a Los Angeles courthouse corridor). 2. Hess v. Indiana, 414 U.S. 105, 105 (1973) (protecting, as freedom of expression, defendant's statement, "We'll take the fucking street later (or again)," made during an anti-war demonstration on a university campus). 3. FCC v. Pacifica Found., 438 U.S. 726 (1978) (upholding the Federal Communications Commission's power to regulate indecent radio broadcasts and involving the radio play of several offensive words, including, but not limited to, "fuck" and "motherfucker"). -

THE ANCESTORS: the Ancestors Need to Be Strong Actor/Singers That Can Carry Solo Work

THE ANCESTORS: The Ancestors need to be strong actor/singers that can carry solo work. There are five ancestors: LAOZI (pronounced LAU-tsi) represents Honor and is the leader of the group. LIN represents Loyalty and is the hardest on Mulan; Lin does not appreciate any challenges to the oldworld belief system. ZHANG (ZANG) represents Strength, the strong silent type. HONG represents Destiny and is Laozi's right-hand man. YUN (YOON) represents Love and is Mulan's greatest advocate from the beginning – the mother figure that eventually encourages the others to support Mulan for who she is. All Ancestors may be cast as either male or female. Vocal Range: A3 – D5. Audition song: “Honor to Us All Part 2”. FA ZHOU (fa zoo): Mulan's father, requires a confident and calm performer who has a strong presence and can sing, at least a little. Without playing "older," his calm strength contrasts with Mulan's frenetic energy at the top of the show. Sings a brief solo. Vocal Range: C4 – D5. Audition song: Choose from any of the audition songs. FA LI: Mulan's mother, is someone who also possesses strength but understands her place in her generation and culture. There is a definite wisdom that she passes on to Mulan. Vocal Range: C4 – D5. Audition song: “Honor to Us All Part 2” or any of the other songs on the audition list. GRANDMOTHER FA: Grandmother sees greatness in Mulan, but still wants her to achieve it through tradition. Although she does not need to be a strong singer, an actor with mischief in her eye will work well here. -

Disney Magic Becomes a Little Less Magical and a Little More

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2019 Vol. 17 majority of Disney films often bequeath the antagonist of Disney Magic Becomes a Little the storyline with a non-American accent, exemplified Less Magical and a Little More by Shere Khan’s British accent in The Jungle Book. The protagonists of the films, like Mowgli in The Jungle Book, Discriminatory are almost always portrayed with the Standard American Kaleigh Anderson accent. It has been a common pattern within Disney’s animated features that characters who speak with non- Storytelling is a crucial part for humankind as well Standard American accents are portrayed as outsiders, as in oral history. Movie adaptations have also become and are selfish and corrupt with the desire to seek or a key ingredient in relaying certain messages to people obtain power. This analysis is clearly displayed in one of of all ages. However, children watching movies and Disney’s most popular animated feature films, The Lion absorbing stories are susceptible and systematically King. In this Hamlet-inspired tale, the main characters’ exposed to a standard (or specific) language ideology accents bring attention to which characters fall into by means of linguistic stereotypes in films and television the “good guy” versus “bad guy” stereotype. Simba, shows. These types of media specifically, provide a the prized protagonist in the film, and Nala, his love wider view on people of different races or nationalities interest, both speak Standard American dialects. Through to children (Green, 1997). Disney films, for instance, linguistic production, Simba’s portrayal as the Lion King are superficially cute, innocent and lighthearted, but translates an underlying message to children viewers through a deeper analysis , the details of Disney movies that characters who are portrayed as heroes or heroines provide, a severe, and discriminating image. -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

Ritters Franchise Info.Pdf

Welcome Ritter’s Frozen Custard is excited about your interest in our brand and joining the most ex- citing frozen custard and burger concept in the world. This brochure will provide you with information that will encourage you to become a Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchisee. Ritter’s is changing the way America eats frozen custard and burgers by offering ultra-pre- mium products. Ritter’s is a highly desirable and unique concept that is rapidly expanding as consumers seek more desirable food options. For the first time, we have positioned ourselves into the burger segment by offering an ultra-premium burger that appeals to the lunch, dinner and late night crowds. If you are an experienced restaurant operator who is looking for the next big opportunity, we would like the opportunity to share more with you about our fran- chise opportunities. The next step in the process is to complete a confidentialNo Obligation application. You will find the application attached with this brochure & it should only take you 20 to 30 minutes to complete. Thank you for your interest in joining the Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchise team! Sincerely, The Ritter’s Team This brochure does not constitute the offer of a franchise. The offer and sale of a franchise can only be made through the delivery and receipt of a Ritter’s Frozen Custard Franchise Disclosure Document (FDD). There are certain states that require the registration of a FDD before the franchisor can advertise or offer the franchise in that state. Ritter’s Frozen Custard may not be registered in all of the registration states and may not offer franchises to residents of those states or to persons wishing to locate a fran- chise in those states. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

The Hercules Story Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE HERCULES STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin W. Bowman | 128 pages | 01 Aug 2009 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752450810 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom The Hercules Story PDF Book More From the Los Angeles Times. The god Apollo. Then she tried to kill the baby by sending snakes into his crib. Hercules was incredibly strong, even as a baby! When the tasks were completed, Apollo said, Hercules would become immortal. Deianira had a magic balm which a centaur had given to her. July 23, Hercules was able to drive the fearful boar into snow where he captured the boar in a net and brought the boar to Eurystheus. Greek Nyx: The Goddess of the Night. Eurystheus ordered Hercules to bring him the wild boar from the mountain of Erymanthos. Like many Greek gods, Poseidon was worshiped under many names that give insight into his importance Be on the lookout for your Britannica newsletter to get trusted stories delivered right to your inbox. Athena observed Heracles shrewdness and bravery and thus became an ally for life. The name Herakles means "glorious gift of Hera" in Greek, and that got Hera angrier still. Feb 14, Alexandra Dantzer. History at Home. Hercules was born a demi-god. On Wednesday afternoon, Sorbo retweeted a photo of some of the people who swarmed the U. Hercules could barely hear her, her whisper was that soft, yet somehow, and just as the Oracle had predicted to herself, Hera's spies discovered what the Oracle had told him. As he grew and his strength increased, Hera was evermore furious. -

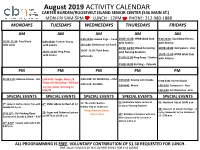

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR CARTER BURDEN/ROOSEVELT ISLAND SENIOR CENTER (546 MAIN ST.) MON-FRI 9AM-5PM LUNCH : 12PM PHONE: 212-980-1888 MONDAYS TUESDAYS WEDNESDAYS THURSDAYS FRIDAYS AM AM AM AM AM 9:30-10:30: Seated Yoga – Irene 10:00-11:00: NYRR Walk Club 9:30-10:30: Soul Glow Fitness 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 9:30-10:30: Forever Young with Asteria with Keesha with Linda with Zandra 10-11:00: Meditation w/ Rondi 10:30- 12:30: Blood Screening 10:00-12:00: Computers - Alex 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 10:45- 11:45: Ping Pong with Nursing Students 10:45-11:45: NYRR Walk Club with Dexter with Linda 11:00-12:00 Ping Pong – Dexter with ASteria 11:00-12:00 Knitting – Yolanda PM PM PM PM PM 12:30-1:30: Balance Fitness - Sid 1:00-4:00: People, Places, & 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop – John 1:00-4:00: Sewing with Davida 12:00-3:00: Korean Social Things Art Workshop – Michael 1:30-4:45: Scrabble 2:00-4:45: Movie 1:00-3:00: Computers - Alex Summer hiatus returning on 9/03/19 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop -John SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS: SPECIAL EVENTS 01: Medication Safety Lecture at 02: Walmart Trip at 10:00 a.m. 5th: JoAnn’s Fabrics Store Trip with 6th: Elder Abuse Lecture at 11 21: The Carter Burden 11 am w/ Nursing Students Davida 10-2 p.m. Gallery Trip at 11:00 a.m.