Micah: a Commentary [Review] / Smith-Christopher, Daniel L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Desk of Fr. Andrew November 15, 2020 33Rd Sunday of Ordinary Time

From the Desk of Fr. Andrew November 15, 2020 33rd Sunday of Ordinary Time I hope you had a blessed week throughout the year in our community with prayer, gratitude, reflection, and also an evaluation of the Just two more Sundays and we will ministry provided by the Michaelite Fathers over the begin the season of Advent. During last century within the Catholic Church in Poland these last two weeks of the season and abroad. of Ordinary Time, we have an op- portunity to reflect on the past litur- Here in North America all parishes where the Mich- gical year. Perhaps that reflection aelite Fathers minister marked the opening of the will encourage us to give thanks to God for all the centennial year with a special Mass for the occa- graces and blessings we have received. That re- sion. The culmination of the jubilee year celebration flection could also invite us to ask God for for- will take place in London, Ontario at the Cathedral giveness for times, talents and treasures misused. of St. Peter, on June 20, 2021 at 4 pm Mass. May these two weeks lead us through our commu- nal and personal prayer to trust and hope in the lov- The challenge - how best to capture and summarize ing care of our God for us. this history and tell the story of thousands of young people who went through our educational facili- Today I want to take this opportunity to share with ties? How to tell the story of hundreds of brothers you a little bit of history. -

Daniel Abraham David Elijah Esther Hannah John Moses

BIBLE CHARACTER FLASH CARDS Print these cards front and back, so when you cut them out, the description of each person is printed on the back of the card. ABRAHAM DANIEL DAVID ELIJAH ESTHER HANNAH JOHN MOSES NOAH DAVID DANIEL ABRAHAM 1 Samuel 16-30, The book of Daniel Genesis 11-25 2 Samuel 1-24 • Very brave and stood up for His God Believed God’s • A person of prayer (prayed 3 • • A man after God’s heart times/day from his youth) promises • A great leader Called himself what • Had God’s protection • • A protector • Had God’s wisdom (10 times God called him • Worshiper more than anyone) • Rescued his entire • Was a great leader to his nation from evil friends HANNAH ESTHER ELIJAH 1 Samuel 1-2 Book of Esther 1 Kings 17-21, 2 Kings 1-3 • Prayers were answered • God put her before • Heard God’s voice • Kept her promises to kings • Defeated enemies of God • Saved her people God • Had a family who was • Great courage • Miracle worker used powerfully by God NOAH MOSES JOHN Genesis 6-9 Exodus 2-40 Gospels • Had favor with God • Rescued his entire • Knew how much Jesus • Trusted God country loved him. • Obeyed God • God sent him to talk to • Was faithful to Jesus • Wasn’t afraid of what the king when no one else was people thought about • Was a caring leader of • Had very powerful him his people encounters with God • Rescued the world SARAH GIDEON PETER JOSHUA NEHEMIAH MARY PETER GIDEON SARAH Gospels judges 6-7 Gensis 11-25 • Did impossible things • Saved his city • Knew God was faithful with Jesus • Destroyed idols to His promises • Raised dead people to • Defeated the enemy • Believed God even life without fighting when it seemed • God was so close to impossible him, his shadow healed • Faithful to her husband, people Abraham MARY NEHEMIAH JOSHUA Gospels Book Nehemiah Exodus 17-33, Joshua • Brought the future into • Rebuilt the wall for his • Took people out of her day city the wilderness into the • God gave her dreams to • Didn’t listen to the promised land. -

Daniel 1. Who Was Daniel? the Name the Name Daniel Occurs Twice In

Daniel 1. Who was Daniel? The name The name Daniel occurs twice in the Book of Ezekiel. Ezek 14:14 says that even Noah, Daniel, and Job could not save a sinful country, but could only save themselves. Ezek 28:3 asks the king of Tyre, “are you wiser than Daniel?” In both cases, Daniel is regarded as a legendary wise and righteous man. The association with Noah and Job suggests that he lived a long time before Ezekiel. The protagonist of the Biblical Book of Daniel, however, is a younger contemporary of Ezekiel. It may be that he derived his name from the legendary hero, but he cannot be the same person. A figure called Dan’el is also known from texts found at Ugarit, in northern Syrian, dating to the second millennium BCE. He is the father of Aqhat, and is portrayed as judging the cause of the widow and the fatherless in the city gate. This story may help explain why the name Daniel is associated with wisdom and righteousness in the Hebrew Bible. The name means “God is my judge,” or “judge of God.” Daniel acquires a new identity, however, in the Book of Daniel. As found in the Hebrew Bible, the book consists of 12 chapters. The first six are stories about Daniel, who is portrayed as a youth deported from Jerusalem to Babylon, who rises to prominence at the Babylonian court. The second half of the book recounts a series of revelations that this Daniel received and were interpreted for him by an angel. -

Micah at a Glance

Scholars Crossing The Owner's Manual File Theological Studies 11-2017 Article 33: Micah at a Glance Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Article 33: Micah at a Glance" (2017). The Owner's Manual File. 13. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Owner's Manual File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICAH AT A GLANCE This book records some bad news and good news as predicted by Micah. The bad news is the ten northern tribes of Israel would be captured by the Assyrians and the two southern tribes would suffer the same fate at the hands of the Babylonians. The good news foretold of the Messiah’s birth in Bethlehem and the ultimate establishment of the millennial kingdom of God. BOTTOM LINE INTRODUCTION QUESTION (ASKED 4 B.C.): WHERE IS HE THAT IS BORN KING OF THE JEWS? (MT. 2:2) ANSWER (GIVEN 740 B.C.): “BUT THOU, BETHLEHEM EPHRATAH, THOUGH THOU BE LITTLE AMONG THE THOUSANDS OF JUDAH, YET OUT OF THEE SHALL HE COME FORTH” (Micah 5:2). The author of this book, Micah, was a contemporary with Isaiah. Micah was a country preacher, while Isaiah was a court preacher. -

(Ph.D)* Micah, Ezekiel Elton Michael**,Aghemelo,Austin Thomas (Ph.D) ***

IJRDO-Journal of Business Management ISSN: 2455-6661 MOTIVATION AND JOB SATISFACTION AMONG FEMALE EMPLOYEES IN FINANCIAL SECTOR IN NIGERIA Akinwunmi Adeboye (Ph.D)* Micah, Ezekiel Elton Michael**,Aghemelo,Austin Thomas (Ph.D) *** Department of Banking & Finance, Achievers University, Owo- Nigeria** Department of Business Administration, Nassrawa State University, Keffi-Nigeria* Department of Political Science, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria*** Email: [email protected] ,Phone: +234-8033-720-666. Abstract A salient factor in this problem is that motivation varies among the individual employees. Thus it is not easy to establish fixed motivational standards and expect full compliances by all employees. Although motivation may include rewards and punishment, Clemmer (1996) feels that it includes ideas, expectations and experiences. Most authors are silent about the effect of gender on employee motivation. However females have achieved a lot in positioning themselves at the top of the various professions in the general allegation of discrimination from their male counterparts who dominate corporate terrains. However, the female by virtue of nature are not fully suited to do certain jobs for either safety reasons or for social reason. Thus females are either excluded from such jobs or allowed to perform only complimentary role, while men play the more prominent roles. In the banking sector, most of the jobs can be performed by both sexes and appraising motivation among either sex will not be with extreme difficulty. The purpose of this paper is to determine the factors that motivate the female staff using First Bank of Nigeria Plc as a case study, and to investigate their levels of motivation, satisfaction and the effects of these on the job performance thereof. -

Notes on Amos 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Amos 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE AND WRITER The title of the book comes from its writer. The prophet's name means "burden-bearer" or "load-carrier." Of all the 16 Old Testament writing prophets, only Amos recorded what his occupation was before God called him to become a prophet. Amos was a "sheepherder" (Heb. noqed; cf. 2 Kings 3:4) or "sheep breeder," and he described himself as a "herdsman" (Heb. boqer; 7:14). He was more than a shepherd (Heb. ro'ah), though some scholars deny this.1 He evidently owned or managed large herds of sheep, and or goats, and was probably in charge of shepherds. Amos also described himself as a "grower of sycamore figs" (7:14). Sycamore fig trees are not true fig trees, but a variety of the mulberry family, which produces fig-like fruit. Each fruit had to be scratched or pierced to let the juice flow out so the "fig" could ripen. These trees grew in the tropical Jordan Valley, and around the Dead Sea, to a height of 25 to 50 feet, and bore fruit three or four times a year. They did not grow as well in the higher elevations such as Tekoa, Amos' hometown, so the prophet appears to have farmed at a distance from his home, in addition to tending herds. "Tekoa" stood 10 miles south of Jerusalem in Judah. Thus, Amos seems to have been a prosperous and influential Judahite. However, an older view is that Amos was poor, based on Palestinian practices in the nineteenth century. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

Meeting God, Again - Micah

1 Meeting God, Again - Micah We’ve been going through a series called Meeting God, Again. If you’re just joining us for the first time, we’ve been walking through the minor prophets in the Old Testament to highlight the character of God, and really, to see what kind of relationship God wants with us. Today we’re talking about the prophet Micah. Like all the minor prophets, Micah deals with sin, judgement and hope… but not just on an individual level… The prophets are addressing sin, judgement and hope on a national level. And as I studied this book, I couldn’t help but wonder: Are we really a “blessed nation”? On one level, I’d say, yeah we’re definitely blessed. We live in a free country! Honestly, I have to say, when my plane landed back in the states after 2 weeks in Israel, I was really glad to see our flag flying high! I’m convinced that we can’t fully appreciate the freedom we have unless we’ve been to a country without freedom - and I only had a small taste of that! So, don’t misunderstand my question: I appreciate and completely respect those that have served our country (like all of my grandfathers) and especially those that have given their lives for our freedom! So yes, on one hand, we’re blessed. But, I’m not convinced we’re blessed in such a way that the wealth and prosperity we have is proof that God is on our side. Think about this: We have everything we need - actually, most of us have more than we need to live. -

The Book of Daniel Its Historical Trustworthiness and Prophetic Character

G. Ch. Aalders, “The Book of Daniel: Its Historical Trustworthiness and Prophetic Character,” The Evangelical Quarterly 2.3 (July 1930): 242-254. The Book of Daniel Its Historical Trustworthiness and Prophetic Character G. Ch. Aalders [p.242] In the January issue of this periodical I endeavoured to throw light upon the turn of the tide which has been accomplished in Pentateuchal criticism during the last decennia. I now want to draw the attention of our readers to another problem of the Old Testament which has been of no less importance in negative Bible criticism. The vast majority of Old Testament students have been wont to deny to the Book of Daniel any historical value and to dispute its real prophetic character. In the case of this book it again was regarded as one of the most certain and unshakable results of scientific research, that it could not have originated at an earlier date than the Maccabean period, and, therefore, neither be regarded as a trustworthy witness to the events it mentions, nor be accepted as a proper prediction of the future it announces. Now as to this date, criticism certainly is receding; and this retreat is characterised by the fact that, in giving up the unity of the book, for some parts a considerably higher age is accepted. Meinhold took the lead: he separated the narrative part (chs. ii-vi) from the prophetic part (chs. vii-xii), and leaving the latter to the Maccabean period claimed for the former a date about 300 B.C.1 Various scholars followed, e.g. -

Haggai 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Haggai 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE AND WRITER The title of this prophetic book is also probably the name of its writer.1 Pieter Verhoef mentioned another possibility: "Koole … compares the way other prophetic books originated, and concludes that Haggai, like Jeremiah, probably dictated his own notes to one or two of his disciples. This procedure would account for the third person, the brevity of the record, and the peculiar use of the formula or revelation."2 Haggai referred to himself as simply "the prophet Haggai" (1:1; et al.) We know nothing about Haggai's parents, ancestors, or tribal origin. His name apparently means "festal" or possibly "feast of Yahweh." This is appropriate since much of what Haggai prophesied deals with millennial blessings. His name is a form of the Hebrew word hag, meaning "feast." This has led some students of the book to speculate that Haggai's birth may have occurred during one of Israel's feasts.3 Ezra mentioned that through the prophetic ministries of Haggai and Zechariah, the returned Jewish exiles resumed and completed the restoration of their temple (Ezra 1See R. K. Harrison, Introduction to the Old Testament, pp. 944-48; E. J. Young, Introduction to the Old Testament, pp. 267-69; G. L. Archer Jr., A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, pp. 407-8; H. E. Freeman, An Introduction to the Old Testament Prophets, pp. 326-32. 2Pieter A. Verhoef, The Books of Haggai and Malachi, p. 13. His reference is to J. L. Koole, Haggai, p. 9. 3E.g., Joyce G. -

Interesting Facts About Micah

InterestingInteresting FactsFacts AboutAbout MicahMicah MEANING: “Who is like Yahweh.” I Micah was a contemporary of: AUTHOR: Micah • Hosea in the Northern Kingdom. TIME WRITTEN: While uncertain, mot of Micah’s prophecies • Isaiah in the court of Jerusalem in the Southern ranged from about 735 B.C. to 710 B.C. Kingdom. POSITION IN THE BIBLE: • 33rd Book in the Bible I At the time of Micah’s ministry, Babylon was still under • 33rd Book in the Old Testament Assyrian domination and would be until: • 11th of 17 books of Prophecy • Babylon would rebel against Assyria in 626 B.C., some (Isaiah - Malachi) 96 years after the Northern Kingdom of Israel fell to • 6th of 12 minor prophets (Hosea - Malachi) Assyria in 722 B.C. • 33 Books to follow it. • Then 16 years later in 612 B.C. Babylon would CHAPTERS: 7 overthrow Nineveh, the capital city of the Assyrians. VERSES: 105 This would be approximately 150 years after God had WORDS: 3,153 spared the city of Nineveh at the preaching of Jonah. OBSERVATIONS ABOUT MICAH: I Judah’s specific sins included: I a of Micah’s book exposes the sins of his own countrymen. • Oppression I a of the book depicts the punishment God is about to send. • Bribery among judges, prophets, and priests I a holds out the hope of restoration once the punishment has • Exploitation of the powerless ended. • Covetousness I Micah was from Moresheth Gath, located some 25 miles • Cheating - Merchants used deceptive weights southwest of Jerusalem on the border of Judah and • Pride Philistia, near Gath. -

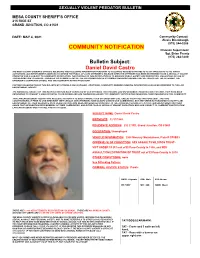

Daniel David Castro Community Bulletin

SEXUALLY VIOLENT PREDATOR BULLETIN MESA COUNTY SHERIFF’S OFFICE 215 RICE ST GRAND JUNCTION, CO 81501 DATE: MAY 4, 2021 Community Contact: Alexis Brumbaugh (970) 244-3206 COMMUNITY NOTIFICATION Division Supervisor: Sgt. Brian Prunty (970) 244-3280 Bulletin Subject: Daniel David Castro THE MESA COUNTY SHERIFF’S OFFICE IS RELEASING THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION PURSUANT TO COLORADO REVISED STATUTES 16-13-901 THROUGH 16-13-905, WHICH AUTHORIZES LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES TO INFORM THE PUBLIC OF A SEX OFFENDER’S RELEASE WHEN THE OFFENDER HAS BEEN DETERMINED TO BE A SEXUALLY VIOLENT PREDATOR AND IS SUBJECT TO COMMUNITY NOTIFICATION. THE PURPOSE OF THIS NOTIFICATION IS TO ENHANCE PUBLIC SAFETY AND PROTECTION. VIGILANTISM, OR USE OF THIS INFORMATION TO HARASS, THREATEN, OR INTIMIDATE ANY OF THE FOLLOWING PEOPLE IS CRIMINAL BEHAVIOR AND WILL NOT BE TOLERATED: THE OFFENDER, THE OFFENDER'S SIGNIFICANT OTHERS, AND THE COMMUNITY NOTIFICATION TEAM. FURTHER DISSEMINATION OF THIS BULLETIN BY CITIZENS IS DISCOURAGED. ADDITIONAL COMMUNITY MEMBERS NEEDING INFORMATION SHOULD BE REFERRED TO THE LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCY. THE INDIVIDUAL SUBJECT OF THIS NOTIFICATION HAS BEEN CONVICTED OF SEX OFFENSES THAT REQUIRE LAW ENFORCEMENT REGISTRATION. FURTHER, THEY HAVE BEEN DETERMINED TO PRESENT A HIGH POTENTIAL TO RE-OFFEND AND ARE THEREFORE SUBJECT TO COMMUNITY NOTIFICATION REGARDING THEIR RESIDENCE IN THIS COMMUNITY. THIS LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCY HAS NO LEGAL AUTHORITY TO DIRECT WHERE A SEX OFFENDER MAY LIVE. UNLESS COURT RESTRICTIONS EXIST, THEY ARE CONSTITUTIONALLY FREE TO LIVE WHEREVER THEY CHOOSE. SEX OFFENDERS HAVE ALWAYS LIVED IN OUR COMMUNITIES, BUT THEY WERE NOT REQUIRED TO NOTIFY LAW ENFORCEMENT OF THEIR RESIDENCE UNTIL REGISTRATION LAWS WERE IMPLEMENTED PURSUANT TO THE JACOB WETTERLING ACT IN 1994.