Africa Falling Off Canada’S Map?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature Review Papers

THE CANADIAN SOUTHEAST ASIA REFUGEE HISTORICAL RESEARCH PROJECT: HEARTS OF FREEDOM LITERATURE REVIEW PAPERS Researchers: Peter Duschinsky, Colleen Lundy, Michael Molloy, Allan Moscovitch, and Stephanie P. Stobbe Unless otherwise noted, papers in the Resources section of this website may be reproduced for educational or non-commercial purposes as long as the use includes acknowledgement of the initial publication on the Hearts of Freedom (HOF) website and a link to the original article. THE CANADIAN SOUTHEAST ASIA REFUGEE HISTORICAL RESEARCH PROJECT: HEARTS OF FREEDOM (HOF) Cambodian Resettlement in Canada: A Literature Review Filipe Duarte, PhD Assistant Professor in School of Social Work at University of Windsor and a Research Assistant for Hearts of Freedom, in association with Carleton University This paper may be reproduced for educational or non-commercial purposes as long as it includes acknowledgement of its initial publication on the Hearts of Freedom website and a link to the original article. Please attribute as follows: Duarte, Filipe. (2020). Background Paper on the Archival Media Research: Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail (1975-1985). https://heartsoffreedom.org/research-papers-literature-reviews/ Abstract This background paper offers a detailed overview of the archival media research conducted on the historical records (microfilms and online databases) of two Canadian newspapers – the Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail, between May 1, 1975, and December 31, 1985. The archival media research reviewed between 20,000 and 25,000 results, on both newspapers, over a five-month period (February-June 2019). Research was undertaken by searching selected keywords identified in the book Running on Empty: Canada and the Indochinese Refugees, 1975-1980, written by Michael J. -

Greetings in Reviewing Our Alumni Records, We Noticed That a Number of Osler Alumni Have Gravitated to the Technology Sector

Keeping Alumni and Other Friends Connected Spring/Summer 2007 the osler link 2 Osler Alumni Embrace the Tech Sector 4 Ebb and Flow Greetings In reviewing our alumni records, we noticed that a number of Osler alumni have gravitated to the technology sector. A former partner in our Calgary office is now a partner in a venture capital firm that funds technology start-ups. A record four former Osler associates – three from our Toronto office and one from our Montréal office – are now corporate counsel at Microsoft. Likewise, the Vice President and Canadian General Counsel for a leading provider of visual information systems was an associate in our Toronto office and the Vice President, Business Development of a major player in the server consolidation and virtualization field was an associate in our Ottawa office. We caught up with these Osler alumni to find Until then, we’d be delighted to hear from you. out what they’re up to and how their Osler Drop us a line so that we can spread your good experiences have shaped their present work. news with your fellow alumni at: We also asked for their views on the state of [email protected]. the tech sector. Their intriguing observations terry burgoyne comprise the centre spread of this issue. We Chair, Osler Alumni Committee hope that you enjoy reading about their pursuits as much as we enjoyed hearing about them. To add to your enjoyment, we’re pleased to announce that our next alumni event will be held this year on Tuesday, October 2nd. The gathering will take place at Jamie Kennedy at the Gardiner Restaurant, Gardiner Museum, Toronto. -

Les Relations Extérieures Du Canada Louise Louthood

Document generated on 10/01/2021 8:59 p.m. Études internationales Chronique des relations extérieures du Canada et du Québec I – Les relations extérieures du Canada Louise Louthood Volume 11, Number 1, 1980 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/701021ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/701021ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Institut québécois des hautes études internationales ISSN 0014-2123 (print) 1703-7891 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Louthood, L. (1980). Chronique des relations extérieures du Canada et du Québec : i – Les relations extérieures du Canada. Études internationales, 11(1), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.7202/701021ar Tous droits réservés © Études internationales, 1980 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ CHRONIQUE DES RELATIONS EXTÉRIEURES DU CANADA ET DU QUÉBEC Louise LOUTHOOD * I — Relations extérieures du Canada (de octobre à décembre 1979) A - Aperçu général L'automne a fourni au gouvernement quelques occasions de préciser l'orientation de sa politique étrangère. Dans les pages qui suivront, nous tenterons de mettre en évidence les événements qui ont caractérisé cette politique. On y retrouvera le « suivi » de dossiers déjà ouverts par l'ancien gouvernement, (par exemple, la question du pipeline de l'Alaska), la conclusion d'initiatives prises récemment (par exemple, l'affaire du déménagement de l'Ambassade d'Israël), la réaction immédiate aux problèmes internationaux de l'heure (Iran, Afghanistan) et, plus généralement, l'esquisse des grandes lignes de la politique étrangère dont on projetait la révision. -

Systemic Corruption in an Advanced Welfare State: Lessons from the Quebec Charbonneau Inquiry Denis Saint-Martin

Osgoode Hall Law Journal Volume 53, Issue 1 (Fall 2015) Understanding and Taming Public and Private Article 4 Corruption in the 21st Century Guest Editors: Ron Atkey, Margaret E. Beare & Cynthia Wiilliams 2015 CanLIIDocs 5215 Systemic Corruption in an Advanced Welfare State: Lessons from the Quebec Charbonneau Inquiry Denis Saint-Martin Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Part of the Social Welfare Law Commons Special Issue Article This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Saint-Martin, Denis. "Systemic Corruption in an Advanced Welfare State: Lessons from the Quebec Charbonneau Inquiry." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 53.1 (2015) : 66-106. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol53/iss1/4 This Special Issue Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Systemic Corruption in an Advanced Welfare State: Lessons from the Quebec Charbonneau Inquiry Abstract The Quiet Revolution in the 1960s propelled the province of Quebec onto the path of greater social justice and better government. But as the evidence exposed at the Charbonneau inquiry makes clear, this did not make systemic corruption disappear from the construction sector. Rather, corrupt actors and networks adjusted to new institutions and the incentive structure they provided. The ap tterns -

Lessons from the Quebec Charbonneau Inquiry

Osgoode Hall Law Journal Volume 53 Issue 1 Volume 53, Issue 1 (Fall 2015) Understanding and Taming Public and Private Corruption in the 21st Century Article 4 Guest Editors: Ron Atkey, Margaret E. Beare & Cynthia Wiilliams 9-4-2015 Systemic Corruption in an Advanced Welfare State: Lessons from the Quebec Charbonneau Inquiry Denis Saint-Martin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Special Issue Article This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Saint-Martin, Denis. "Systemic Corruption in an Advanced Welfare State: Lessons from the Quebec Charbonneau Inquiry." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 53.1 (2015) : 66-106. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol53/iss1/4 This Special Issue Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Systemic Corruption in an Advanced Welfare State: Lessons from the Quebec Charbonneau Inquiry Abstract The Quiet Revolution in the 1960s propelled the province of Quebec onto the path of greater social justice and better government. But as the evidence exposed at the Charbonneau inquiry makes clear, this did not make systemic corruption disappear from the construction sector. Rather, corrupt actors and networks adjusted to new institutions and the incentive structure -

Table of Contents

VOLUME 16 • NUMBER 2 • FEBRUARY, 2012 Table of Contents - SPECIAL ISSUE review Introduction 129 Redrawing Security, Politics, Law And Rights: Reflections On The Post 9/11 Decade Alexandra Dobrowolsky and Marc Doucet, Guest Editors Articles 139 The Post-9/11 National Security Regime in Canada: Strengthening Security, Diminishing Accountability Reg Whitaker 159 Failing to Walk the Rights Talk? Post-9/11 Security Policy and the Supreme Court of Canada Emmett Macfarlane 181 Insecure Refugees: The Narrowing of Asylum-Seeker Rights to Freedom of Movement and Claims Determination Post 9/11 in Canada Constance MacIntosh 211 Governing Mobility and Rights to Movement Post 9/11: Managing Irregular and Refugee Migration Through Detention Kim Rygiel 243 Counter-Terrorism In and Outside Canada and In and Outside the Anti-Terrorism Act Kent Roach 265 The Role of International Law in Shaping Canada’s Response to Terrorism Frédéric Mégret Book Review 287 From Counter Terrorism to National Security: Review of The 9/11 Effect: Comparative Counter-Terrorism, Kent Roach Adam Tomkins Redrawing Security, Politics, Law and Rights: Reflections on the Post 9/11 Decade Alexandra Dobrowolsky* Marc G. Doucet* September 11, 2011 marked the ten-year anniversary of that tragic and fate- ful day when four hijacked airliners crashed into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania, killing 2,997 people. Over the last decade, the aftershocks of these terrorist attacks on the US have certainly been felt the world over, including in one of its closest, proximal, neighbours, Canada. While initial responses claimed that 9/11 “changed everything,” this spe- cial issue explores and evaluates whether and/or how this was the case for Canada. -

Race and Sex Equality in the Workplace: a Challenge and an Opportunity

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 198 ?62 CE 028 080 AUTHOR Jain, Harish C., Ed.: Carroll; Diane, Ed. TITLE Race and Sex Equality in the Workplace: A Challenge and an Opportunity. Proceedings of a Conference (Hamilton, Ontario, September 28-29, 1979). FEPORT NO ISBN-0-662-10886-8 PUB DATE 80 NOTE 225p. EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Affirmative Action: Civil Fights: *Civil Rights Legislation: Employment Practices; *Equal Opportunities (Jobs) :Federal Legislation: Job Layoff; Personnel Integration: Promotion (Occupational): *Racial Discrimination: *Salary Wage Differentials: Seniority: *Sex Discrimination: Sex Fairness IDENTIFIERS Canada; Ontario: United States ABSTRACT These proceedings contain the addresses and panel and workshop presentations made at the September 1979 Conference on Race and Sex Equality in the Workplace: A Challenge and an Opportunity. (Purpose of the conference was to promote a better understanding of human rights legislation and current equal employment and affirmative action programs and to recommend action-oriented equal employment, compensation, and affirmative action policies.) Three welcoming and four opening addresses are presented first. Nineteen presentations made during three panels and three workshops are then provided. Topics for both the panels and workshops are equal pay, affirmative action, and seniority, promotions, and layoffs. Other conference addresses include (1)Promotions, Layoffs, and Seniority under the Antidiscrimination Laws of the United States, (2) I Recommend an "Industrial Relations" Approach to Race and Sex Equality in the Workplace, and (3) Implications for Policy-Markers, a summary of the conference. (YLB) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ************************************************4********************** Race and Sex Equality in the WorkOace: A Challenge and an Opportunity Edited by Harish C. -

January 2020 the Canadian South East Asia Refugee Historical

January 2020 The Canadian South East Asia Refugee Historical Research Project: Hearts of Freedom Background paper on the archival media research: Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail (1975-1985) Dr. Filipe Duarte Assistant Professor School of Social Work University of Windsor Ontario This background paper offers a detailed overview of the archival media research conducted on the historical records (microfilms and online databases) of two Canadian newspapers – the Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail, between May 1, 1975, and December 31, 1985. The archival media research reviewed between 20,000 and 25,000 results, on both newspapers, over a five- month period (February-June 2019). Research was undertaken by searching selected keywords identified in the book Running on Empty: Canada and the Indochinese Refugees, 1975-1980, written by Michael J. Molloy, Peter Duschinsky, Kurt F. Jensen and Robert Shalka. The keywords identified were: refugees, boat people, southeast Asian, Indochinese, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnamese, Cambodian(s), Laotian(s), resettlement, and sponsorship. Subsequently, the analysis of the press clipping then proceeded by grouping the findings according four different categories and stages: (1) beginning of the arrival of refugees (migration journey, etc.); (2) public and political/government opinions; (3) sponsorship – individuals, churches and groups; and (4) resettlement and integration into Canadian society. The beginning of the arrival of refugees The analysis of the findings under the first category – “beginning of the arrival of refugees”, showed that, the first refugees, a family of five, landed at Toronto airport on May 8, 1975. They had already a family member living in Toronto. One month earlier, 53 orphans also arrived in Canada. -

Connectionconnection

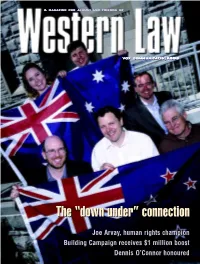

A magazine for alumni and friends of vox communitatis|2003 TheThe “down“down under”under” connectionconnection JoeJoe Arvay,Arvay, humanhuman rightsrights championchampion BuildingBuilding CampaignCampaign receivesreceives $1$1 millionmillion boostboost DennisDennis O’ConnorO’Connor honouredhonoured [ Contents ] Features A PLUMBER WITH WORDS ...................................................................... 10 Joe Arvay uses the Charter as a tool to advance human rights LEARNING “DOWN UNDER” .................................................................... 14 Western Law has forged strong academic ties with Australia and New Zealand THE JANUARY TERM ................................................................................ 17 Simon Evans, University of Melbourne, describes his month-long stay at Western Law HONORARY DOCTORATE FOR CHIEF JUSTICE O’CONNOR..................... 18 Former Western Law professor is honoured at convocation NEVER A DULL MOMENT ......................................................................... 20 In an anything-but-conventional career, Ron Atkey has found a way to combine his many interests INFORMATION & TECHNOLOGY LAW AT WESTERN ............................... 23 Q&A with Professor Margaret Ann Wilkinson JUDGE-IN-RESIDENCE ............................................................................. 25 Madame Justice Lynne Leitch reflects upon her year at Western Law FINAL ARGUMENT .................................................................................... 47 Democratic Deficit: Is it -

Bulletin-81A-Final.Pdf, Unknown

Issue #81 July 2017 ISSN 1485-8460 Our Book is Out! Running on Empty: Canada and the Indochinese Refugees, 1975-1980 was written by Michael J. Molloy, Peter Duschinsky, Kurt F. Jensen, and Robert Shalka, and published this year by McGill-Queen’s University Press. Part of the McGill-Queen’s Studies in Ethnic History Series (number 2.41), it is 612 pages long and is available in cloth, paperback, and e-book. Contents Message from the President Michael Molloy 2 Launching the Book 2 Canada: Day 1 6 The Health of the Indochinese Refugees, Then and Now Brian Gushulak 7 Visioning Workshop, Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 10 Carmen et César Christian Labelle 11 Kosovar Evacuation: Donation to Pier 21 14 In Memoriam 14 1 Message from the President Over the past 30 years, our little Society has done big things: world class conferences on the Hungarian, Ugandan and Indochinese refugee movements, the Ugandan Asian online archive at Carleton University, and the Gunn Prize, to name some of the more important. The publication of Running on Empty: Canada and the Indochinese Refugees, 1975-1980 as part of McGill-Queen’s University Press’s prestigious Studies in Ethnic History Series is another major milestone for CIHS. The current issue of the Bulletin reports on the events that have helped publicize this important book. More will follow. Our satisfaction with the publication of Running on Empty and its initial reception are, however, tinged with sadness at the sudden passing of Ronald Atkey, the Immigration minister who launched the refugee movement that inspired our book. -

Leadership Canada Adrift in a World Without Leaders

2019 THOMAS D’AQUINO LECTURE ON LEADERSHIP CANADA ADRIFT IN A WORLD WITHOUT LEADERS AN ADDRESS BY THE THE HONOURABLE PERRIN BEATTY, P.C., O.C. PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER CANADIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE © Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information retrieval systems – without the prior written permission of the publisher. Canada Adrift in a World Without Leaders, an address by the Honourable Perrin Beatty, P.C., O.C. for the Thomas d’Aquino Lecture on Leadership London Lecture: October 9, 2019; Ivey Business School, London, Ontario Ottawa Lecture: November 6, 2019; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario Report prepared by the Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership, Ivey Business School, Western University. Suggested citation: Beatty, Perrin. Canada Adrift in a World Without Leaders Editor, Kimberley Young Milani. Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership: London, ON, 2019. London Event Photographer: Gabriel Ramos Ottawa Event Photographer: Andrew Van Beek, photoVanBeek Studio Cover image: The Honourable Perrin Beatty, Ivey Business School at Western University Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership Ivey Business School 1255 Western Road London, Canada N6G 0N1 Tel: 519.661.3890 E-mail: [email protected] Web: ivey.ca/leadership 2 | Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership THOMAS D’AQUINO Chairman & Chief Executive Intercounsel Ltd. Photo by Jean-Marc Carisse Thomas d’Aquino is an entrepreneur, corporate director, leadership of the Council in its formative stages. -

2008 (Pdf, 1.00

ALUMNI MAGAZINE | 2008 A Perfect Match DAVID SHOEMAKER ’96 BRINGS WOMEN’S TENNIS TO CENTRE COURT WHAT’S INSIDE WAR & PEACE IN SIERRA LEONE PROF. CRAIG BROWN ON WHY LAWYERS LOVE GOLF PROF. RICHARD MCLAREN AND BASEBALL’S MITCHELL REPORT A GREAT CASE – JOHN PELLER ’80 - CANADA’S LEADING VINTNER THE MAGIC OF DAVID BEN ’87 w w w .la It’s Your Law Alumni Association w .uw o Law Alumni Events for You .ca ANNUAL WESTERN LAW ALUMNI DINNER HOMECOMING Save the date! Law Alumni Association Annual General Meeting Wednesday, October 22, 2008 Saturday, October 4, 2008 at 9:30 a.m. The Great Hall, Somerville House, Dean’s Boardroom, Faculty of Law The University of Western Ontario Manulife South End Zone Lunch and Football Game REUNIONS Saturday, October 4, 2008 at 11:00 a.m. When you contribute to Western Law, you help support students and Did you graduate in a year ending in 3 or 8? TD Waterhouse Stadium, The University of Western Ontario If you’re interestefda tcou sletey i fw a hreou nairoen aist b tehineg h eart of Western Law’s tradition of excellence. planned for youYro culars sg oifr ty oisu twhoeu lbde liskte wtoa gye tt o have Aa LmUMeaNnI iDnEgNfNuIlN imG NpIaGcHtT o InN tThOeR OlaNwT Osc hool. one going please contact Nicole Bullbrook at Date to be announced (March 2009) [email protected] For more information about the above events visit www.alumni.uwo.ca Serving more than 5,900 alumni world-wide, The University of Your UWOLAA Executive Western Ontario Law Alumni Association (UWOLAA) aims to: President, Richard J.